Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sekforde Street area', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, (London, 2008) pp. 72-85. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp72-85 [accessed 11 April 2024]

In this section

CHAPTER II. Sekforde Street Area

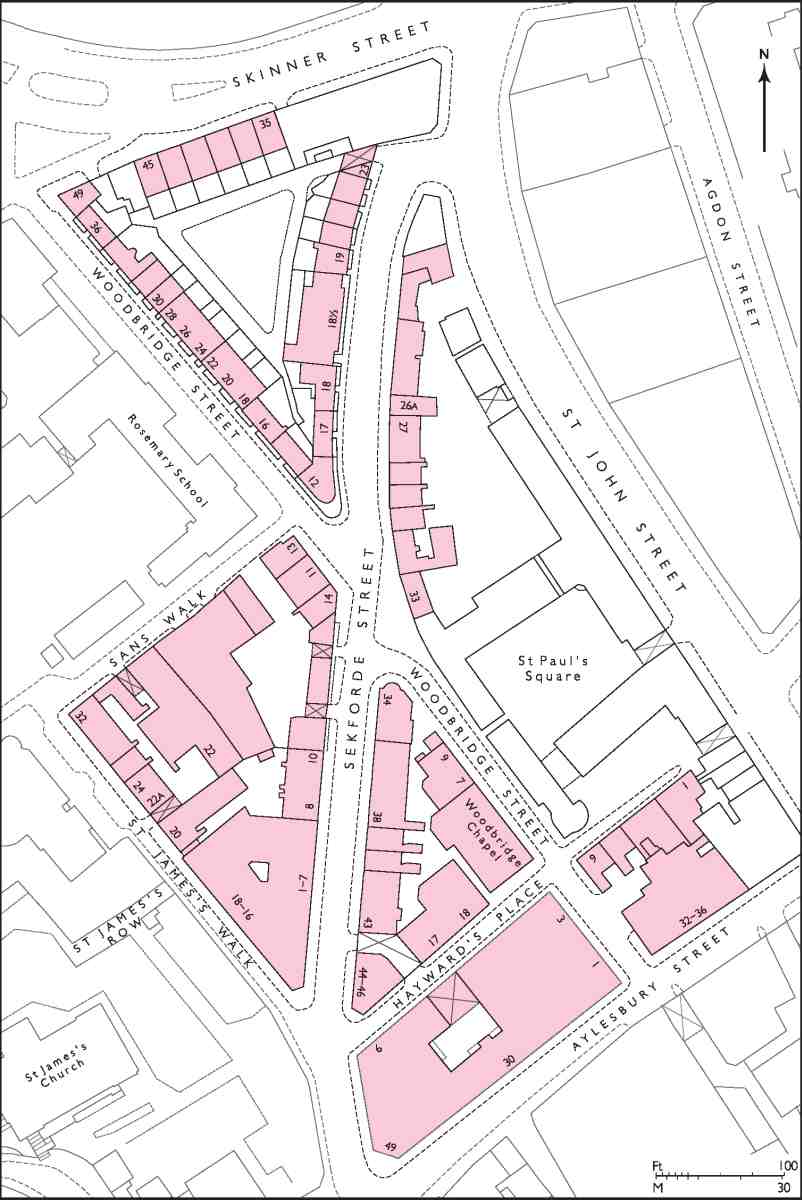

71. Sekforde Street area

Sekforde Street takes its name from an Elizabethan man of law, Thomas Seckford, or Sekforde, who bequeathed a part of his Clerkenwell estate, the subject of the present chapter, to endow almshouses in the town of Woodbridge in Suffolk. The Seckford Charity, now the Seckford Foundation, continued as landlord until the 1970s. The area extends from the west side of St John Street between Aylesbury Street and Skinner Street, to Woodbridge Street, Sans Walk, St James's Walk and the south end of Sekforde Street (Ill. 71). Individual buildings fronting St John Street, and the whole of the large site formerly occupied by Nicholsons' Distillery (St Paul's Square), are discussed more fully in Chapter VIII.

Both Sekforde Street and Woodbridge Street, the two principal streets crossing the estate, date from the late 1820s when what had been a fairly haphazard accumulation of alleys and courts, largely industrial in character but with many small houses and tenements, was almost completely re-planned. Most of the houses standing today were built during the following decade and a half, along with Woodbridge Chapel in Hayward's Place and the former Finsbury Savings Bank in Sekforde Street. A very few earlier buildings remain, including the former Woodbridge House of c. 1808, the successor to a house built and occupied by Seckford himself. (fn. 1)

Seckford's Charity and the Seckford Estate

Thomas Seckford (c. 1517–87) came from a long-established landed family, whose principal seat was Seckford Hall, near Woodbridge. A lawyer and MP, he rose to some eminence under Elizabeth I, becoming Master of the Court of Requests and Surveyor to the Court of Wards and Liveries, among other appointments. Through his royal connections he became patron of the cartographer Christopher Saxton, and he also supported the topographer William Harrison, author of the Description of Britayne. In 1557 he married Elizabeth, widow of Sir Martin Bowes, a former Lord Mayor of London. She died childless in Clerkenwell in 1586, and in December the following year Seckford himself died.

In addition to the endowment estate, Seckford left other land and several houses in Clerkenwell, including a house on the site of the future Hugh Myddelton School in Sans Walk, which he hoped would become the London home of the Seckford family (see page 54). (fn. 2)

As directed by Seckford, the revenue from the Clerkenwell estate was to be placed in the hands of two governors—the Lord Chief Justice of Common Pleas, and the current owner of the property so long as this was a male heir in the Seckford line (the estate having been entailed to the male line some years previously). Failing this, responsibility was to pass to the Master of the Rolls.

Disputation and legal wrangling by members of the family over many years threatened to wreck the foundation, beginning with the contesting of his will by Thomas's nephew and heir, Charles Seckford, and Thomas's younger brother Henry. The situation was complicated by the rapid succession of the estate from heir to heir. Charles died in 1592, and following the demise of Henry, and Charles's sons and grandsons, the estate passed in 1626 to another nephew of the founder, also Henry, the last of the male Seckfords. This Henry was obliged to fight out a rival claim by Charles's granddaughter Mary and her husband, Sir Anthony Cage. With Henry's death in 1638 the Seckford family's role in the charity came to an end, the Master of the Rolls replacing him as governor. (There was further trouble, however, for in 1650 a distant member of the family, John Gibbon Seckford, seized the estate as his own, and had to be ejected by force of arms.)

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the Seckford estate underwent piecemeal development, becoming densely built up on the most ad hoc plan. By the 1820s it was 'one of the least desirable parts of Clerkenwell'. (fn. 3) Redevelopment of most of the estate from the late 1820s generated a far greater rental than the original modest scope of the charity required, and in 1838–42 a new almshouse, the Seckford Hospital, was built in Woodbridge to absorb some of this money. Calls continued, however, for some of the Seckford income to be diverted to the impoverished Woodbridge Free Grammar School, founded in 1662 and endowed by, among others, Dorothy Seckford (widow of Thomas's nephew Henry). In 1861 the charity was reformed under a new scheme providing for the rebuilding of the original almshouses, and the provision of a public dispensary, library, pump and drinking-fountain; part of the surplus income was allocated to the grammar school, which was rebuilt and reconstituted as a public school. Local administration of the combined charities was ceded to a new board of trustees, who in 1868, following the objections of the Lord Chief Justice, Sir William Bovill, to his role as governor, also assumed control of the Clerkenwell estate, with direct responsibility to the Charity Commissioners.

The eventual disposal of the estate came about with its declining fortunes after the Second World War. There were allegations in the press about the slummy state of the property from 1950, and by the 1970s many businesses were folding and it was difficult to find new commercial tenants. The greater part was sold in 1975 to the London Borough of Islington. Most of the remainder, two large commercial buildings, was sold in 1980, leaving just one property, disposed of in the early 2000s. (fn. 4)

The estate before c. 1827

When Thomas Seckford bought the estate in 1566 it formed the larger part of a field, called St Mary's Close after the nunnery of St Mary to which it had belonged until the Dissolution. (The smaller, western portion, now occupied mainly by the former Hugh Myddelton School, is dealt with in Chapter I.) By the time of his death the ground had been enclosed with a brick wall, laid out with walks, sub-divided, mostly into gardens, and partly built on. There were two houses: his own residence and a smaller house adjoining, each with its own grounds; a gatehouse, other outbuildings and a stable-yard. (fn. 5)

Neither this nor subsequent development in the seventeenth century can be traced with much confidence, though Seckford's own residence is almost certainly identifiable as Woodbridge House. By 1635, when new leases were granted to improve the rental, the estate had been considerably built over and was described as consisting of 'houses very much out of repair'—a state of affairs to which the contested ownership of the estate may have contributed. (fn. 6) The same impression of dilapidation is given by a building lease of 1679, which refers to the existence of old timber-framed buildings, ruinous and empty for some time. These buildings probably included the remains of the Red Bull Theatre, which stood on or close to the corner of St John Street and Aylesbury Street. (fn. 7)

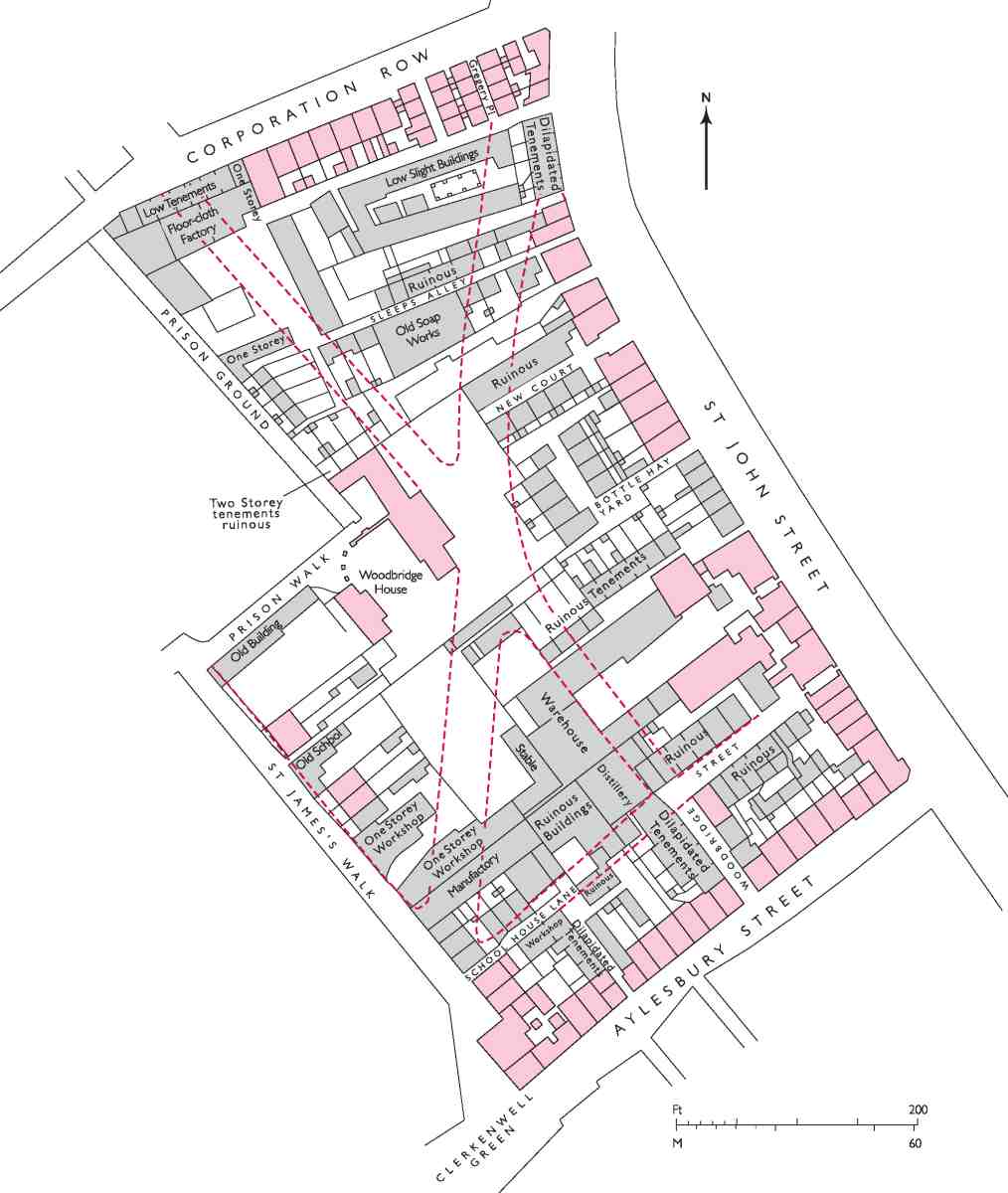

In 1767 new 60-year leases were granted of six plots making up the estate, which perhaps perpetuated the sixteenth-century divisions. The lessees—mostly local brewers or distillers—undertook to spend between them a total of £14,700 on improvements. (fn. 8) Of these, all that remains today is a terrace of houses in Skinner Street (now Nos 35–45, formerly numbered in Corporation Row). Most of the new building was probably industrial. Illustration 72 shows the maze-like arrangement and dilapidated state of the buildings standing at the expiry of the leases in the 1820s. Commercial buildings and dwellings alike stood in ruins, and it is likely from the various bare patches of ground that others had already been pulled down. At the centre, only twenty years old, was the rebuilt Woodbridge House.

Improvements and redevelopment, 1827–c. 1842

Fortuitously, just as the leases on the estate were about to fall in, the Seckford governors found themselves with money in hand—the proceeds of minor land sales to the local authorities for widening the footpath in Corporation Row and extending the site of the New Prison. Much of this surplus was used to obtain a private Act, passed in 1826, authorizing leases of up to 99 years to be granted. (fn. 9) The subsequent redevelopment was in fact carried out almost entirely on 75-year leases. New roads and sewers were provided by the charity, the cost being met initially from sales of old materials and later recouped from individual builders through ground rents or one-off payments. Progress was hampered for some years, however, by the widespread slump in the building trade, and the charity had to lower its sights as regards ground rents in order to let the ground.

The scale of the operation necessitated some improvements in the estate management. These included the appointment of a separate receiver (a role hitherto combined with that of solicitor), and a surveyor. The choice for this last fell on C. R. Cockerell, surveyor to the adjacent Northampton Estate, a family friend of Sir John Leach, the Master of the Rolls. Leach had originally trained as an architect under Sir Robert Taylor, a fellow pupil being Cockerell's father, S. P. Cockerell. He remained a family friend, becoming the son's confidante and adviser, and commissioning architectural work from him in a private capacity. (fn. 10)

In practice, much of the work of overseeing the development was done by Cockerell's capable assistant James Noble. By the late 1830s Noble had taken over more or less completely, and subsequently superseded Cockerell in all the charity's estate-management business, not only in Clerkenwell. He was still acting as surveyor at the time of his death in 1875. (fn. 11)

The leading role in the Charity's affairs continued to be taken by the Master of the Rolls, though both he and the Lord Chief Justice left the day-to-day running of the estate to its paid officers. There were three Masters during the main rebuilding period: Leach (1827–34); Sir Charles Pepys (1834–6), and Henry Bickersteth, Lord Langdale (1836–51). Sir William Draper Best served as Lord Chief Justice of Common Pleas from 1824 to 1829, when he was succeeded by Sir Nicholas Conyngham Tindal, who held office until 1846.

Cockerell and Noble had a new layout for the estate ready by August 1827. Two new thoroughfares were planned, crossing at the centre of the ground: a main road, Sekforde Street, and a narrower counterpart, Woodbridge Street. The new streets were arranged so that clearance was largely restricted to ruinous properties (Ill. 72). Existing houses fronting St John Street, Aylesbury Street and Corporation Row were nearly all retained, as were a few in St James's Walk.

Noble was prevented by the Master of the Rolls from razing the courts at the east end of Corporation Row, which had been built up about 1780, and consequently Sekforde Street ran awkwardly into St John Street right behind them. Years later he contended that had Sekforde Street been carried through as intended, 'all the Building would have let earlier and at a better price'. (fn. 12)

Most of the early redevelopment was non-domestic: Nicholsons' new distillery in St John Street; a wallpaper factory and a mahogany warehouse, both additions to premises fronting St John Street; livery stables at the top end of Sekforde Street; a builder's workshops and a new parochial school, both in St James's Walk. Housebuilding, in contrast, got off to a bad start, with the rapid failure of the first comer, John Bewley of Kingsland Road, a salesman turned builder. Bewley's take was the block bounded by Sekforde Street, Woodbridge Street and Suffolk Street (now part of Hayward's Place), and he was given the go-ahead to clear the site in November 1827.

72. Sekforde estate in the late 1820s. Proposed streets are indicated by broken red line, ruinous buildings in grey

Bewley also took a lease of the Noah's Ark public house, over the road from his ground on the corner of what became Hayward's Place and Woodbridge Street, the plan being to turn it into a private dwelling and transfer the licence to the new pub he was building (the present Sekforde Arms). But he could not afford to buy out the existing tenant, and although Noble was eventually able to persuade the charity to assist, the delay seems to have effectively scuppered Bewley's development. He was in any case proving to be an unsatisfactory builder, using 'old rotten wood' for partitions, and mortar 'very little better than Garden Soil'. (fn. 13)

By August 1829 the Sekforde Arms had been completed and the licence transferred, and Bewley had also managed to build three carcases of houses adjoining, in Sekforde Street, as well as pavement vaults for the rest of his intended houses. That was the end of Bewley's building activities on the estate, though it was not until 1832 that a final settlement was made with him, under which he kept only the Sekforde Arms.

Bewley's failure precipitated something of a crisis. Already builders were showing little interest in taking plots and some of those previously committed were reluctant to proceed. The only other houses built so far were two in Suffolk Street. In 1830 Nicholsons were unwilling to erect a house as agreed at the rear of their distillery, because nothing else had been built on that part of the estate.

Early in 1831, Henry Johnson, a bricklayer of Charterhouse Lane who had already been employed to construct the sewers and the rest of the pavement vaults on the estate, was approached to build up some of Bewley's vacant plots, and undertook to complete Bewley's carcases and do up the Noah's Ark. He also took on the redevelopment of the derelict Woodbridge House and the building of a couple of houses in Sekforde Street adjoining the mahogany warehouse. In June he further agreed to put up four houses at the northern end of St James's Walk, backing on to the land he had already acquired in connection with Woodbridge House, a venture in which he was joined by a 'very respectable Builder'—presumably Charles Hellis, who set up his yard on the adjoining site. (fn. 14)

Johnson became closely involved with the estate, taking on the role of unofficial agent and doing building repairs and remedial work on the still-unmade roads. He sold reclaimed bricks to other builders there and, as well as putting up his own houses, occasionally built for other developers. By 1835 he seems to have established a substantial business, and was engaged on 'two very extensive jobs in the Country'. After his death in 1843 the business was carried on by his son Henry, who in about 1850 moved the 'London Offices' from Woodbridge House to Hatton Garden, although retaining a yard in St James's Walk. (fn. 15)

Redevelopment continued through the 1830s with the building of Woodbridge Chapel in 1832–3 and the eastern half of present-day Hayward's Place in 1834–6. The east side of Woodbridge Street was completed in 1837, the west side over the next three years. The greater part of Sekforde Street was completed during the same period. In November 1839 Noble was able to report that 'matters have within a few months rapidly advanced towards completion', (fn. 16) and by May 1840 all the ground at Clerkenwell had been let.

Design and planning

Given the character of the district generally, nearly all the new houses were of the third rate. Fourth-rate cottages were allowed in Hayward's Place, considered the least desirable part of the estate, but a proposal for erecting three 'trumpery tenements' in a court off Woodbridge Street was given short shrift. (fn. 17) Conventional in design, the houses mostly have round-arched doorways and groundfloor windows, and first-floor windows set in sunk panels beneath relieving arches. Their one distinguishing feature is the treatment of the parapets as a rudimentary diglyph frieze. The doorcases show variants of Classical decoration, and the fanlights and area railings are of standard patterns. A number of 'Gothick' glazing bars survive.

Plans and elevations of all buildings had to be agreed with the estate surveyor, in practice with Noble, who remarked in 1828 that the first houses built would 'in some degree form a criterion' for those to follow. (fn. 18) Bewley's elevations were drawn up for him by the architects Griffith & King, of St John's Square, who may have introduced the diglyph-frieze feature. Thereafter, builders were not necessarily required to submit drawings, but where they did not it was assumed they would follow the precedent of houses already built. Some deviations were permitted: for instance, Noble conceded that the northernmost houses on the west side of Sekforde Street (Nos 22 and 23) were too tall, but the developer had 'employed an Architect and I could not object to superior property being erected'. (fn. 19) Johnson's houses adjoining the mahogany warehouse (Nos 25 and 26 Sekforde Street) are also of a different pattern to most of those on the estate, having stuccoed ground-floor fronts and lacking arched recesses on the first floor.

First-floor windows were generally the same height as those on the ground floor rather than lengthened to create a piano nobile effect. In 1837, when a prospective tenant, James Smith, wished to lengthen the first-floor windows of No. 37 Sekforde Street, Noble was delighted to get someone 'so respectable as not to object to shewing his Drawing Room Floor'. The existing windows had been designed 'to reduce the expense, and as more suitable to the habits & means of the parties, who were likely to occupy the Houses'—a reference perhaps to poor furnishing, the use of drawing-rooms as bedrooms, or even sub-letting'. (fn. 20) Smith, a bricklayer active in building on the estate, was probably involved in building the houses immediately to the south (first leased to James Whiting, carpenter), which have similarly tall first-floor windows.

A number of the houses are double-fronted, the main concentration being on the shallow plots at the northern angle of Woodbridge and Sekforde Streets. The type seems to have been introduced here by John Gould, a carpenter-builder of Skinner Street, from the adjoining Skinners' Company estate, where a similar street pattern had left many shallow plots.

Noble was keen that the few non-domestic buildings should enhance the overall scheme, the now-demolished mahogany warehouse in Sekforde Street demonstrating his own architectural creativity. Woodbridge Chapel follows much more closely the unpretentious style of the houses, while Alfred Bartholomew's Finsbury Savings Bank is in a showy Italianate style, thought appropriate for banks: Noble was very pleased with the result. He also ensured that the treatment of the boundary wall in Sekforde Street at the back of Nicholsons' distillery was given an architectural treatment (Ill. 73); he was, however, unable to prevent it being topped with chevaux-de-frise (since removed) which he thought prison-like.

73. Woodbridge Street, east side in 2004, showing Nicholsons' Distillery wall. John Blyth, architect, 1838–9

Character of the estate after redevelopment

The new houses were largely occupied by skilled craftspeople, often with apprentices or clerks lodging with them, and typically engaged in making jewellery, clocks and watches, working precious metals, building, printing and the book trade. Many of these people worked at home in makeshift workrooms, or back-yard workshops—to which the Estate offered no objection, provided they were substantially built.

There were many shops, particularly in St John Street and Aylesbury Street. In addition to Nicholsons' gin distillery there were some larger industrial and commercial concerns, including a brass foundry in Woodbridge Street; a feather-bed warehouse, later an indigo works, facing Clerkenwell Green at the bottom of St James's Walk (No. 48 Clerkenwell Green, see page 114); the Daffy's Elixir warehouse in Woodbridge Street; and Alexander Croll's gas-meter factory in Hayward's Place.

John Groom's Watercress and Flower Girls' Christian Mission

The Seckford estate had a long association with the evangelist John Groom and the Watercress and Flower Girls' Christian Mission, founded by him in 1866 to help some of the lowliest of the London street-vendors. Begun in Harp Alley in the City, near the Farringdon fresh-produce market, the mission became established in Clerkenwell, where Groom lived and worked at No. 8 Sekforde Street from 1875 as a machine engraver or 'engine-turner'. It became well-known for the manufacture of artificial flowers by disabled girls and women, and for establishing orphanages and holiday homes for disabled children at Clacton-on-Sea. From the 1870s until the late 1960s the mission occupied a number of buildings in and around Sekforde Street, including several houses comprising the residential 'Crippleage', Woodbridge Chapel, the old parochial school in St James's Walk, and purpose-built factories and warehousing in St James's Walk and Hayward's Place. (fn. 21)

The flower-making seems to have begun in 1879 with the foundation of the 'Flower Girl Brigade' by the philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts. She pressed Groom to devote himself to it full-time, and this he agreed to do provided she paid for a manager to carry on his engraving business, an arrangement which lasted until her marriage in 1881. She then gave up the Brigade entirely, which was continued by Groom as the 'industrial branch' of the mission, his manager's salary being paid out of the proceeds. (fn. 22)

For many years Sunday services were held by the mission at Foresters' Hall, Clerkenwell Road. In the 1880s a mission Sunday school was held in Bowling Green Lane School, and classes and flower-making were later conducted in an old building in Clerkenwell Close occupied by a firm of bookbinders. In the 1890s the closure of Foresters' Hall as a public meeting-place prompted the acquisition of Woodbridge Chapel and the conversion of the vaults to replace the Clerkenwell Close premises. (fn. 23)

Operations were largely transferred to Edgware in the 1930s, and the charity's connection with Clerkenwell came to an end in 1967 when the head office was moved from No. 37 Sekforde Street. The organization continues today as John Groom's Association for the Disabled.

74, 75. Woodbridge House, No. 30 Aylesbury Street; factory of 1936–9, converted to offices. Exterior in 1994 and (right) central atrium in 1996

Aylesbury Street (north side)

The north side of Aylesbury Street was left unaltered by the estate improvements of the early nineteenth century, but none of the old houses now survive and the frontage is occupied by two buildings, which together take up the whole block between Aylesbury Street and Hayward's Place.

Woodbridge House (No. 30) was built speculatively in 1936–9 as factory units by the Seckford Charity. The architects were the factory specialists Fuller, Hall & Foulsham. (fn. 24) It was revamped in 1990 as offices for a legal firm, by Barry Todd Associates (Ills 74, 75).

Nos 32–36, also by Fuller, Hall & Foulsham, was purpose-built as a printing works in 1962–3. (fn. 25) The reinforced-concrete frame is filled with brick and aggregate panels.

Hayward's Place

Hayward's Place was created in the early 1830s as Suffolk Street, taking in parts of two existing thoroughfares: Woodbridge Street, formerly Red Bull Yard (the rest of which was extended northwards to form the present-day Woodbridge Street), and School House Lane (see Ill. 72).

The eastern part of the street was soon renamed Hayward's Place, after its developer, while the western half retained the original name until 1908. Though none of the old fabric remains, the arched pedestrian entry from St John Street is a relic of the pre-1820s arrangement of Red Bull Yard, probably dating back to the sixteenth or seventeenth century.

James Hayward, the son of a City glass-merchant, was uncle of the founders of the firm Hayward Brothers of the Borough, makers of manhole covers and pavement lights. (fn. 26) In 1827 he set up as an ironmonger and manufacturer of 'Improved Gas or Lamp-smoke Consumers' in Aylesbury Street, moving to St James's Walk in the 1840s. Over the years his activities also included auctioneering and surveying, lock-making and brass-founding. He became a prominent figure in parish affairs, and acquired a number of properties on the Seckford estate, leasing existing houses and building others.

Hayward's Place, his most concentrated development, built by Henry Johnson in 1834–6, consisted of two rows of houses on either side of the street, and a pair in Woodbridge Street, on the north corner with Hayward's Place. (fn. 27) They were acquired by Nicholsons about 1871, and in 1882 the northern row was demolished for expansion of their distillery. (fn. 28) By 1891 those remaining were largely inhabited by Nicholsons' employees. (fn. 29)

76. Hayward's Place in 2006, looking east to St John Street

Four of the original buildings survive (Nos 1–4, originally 2–5). They have channelled stucco on the ground floor and, like the larger houses on the estate, a simple diglyph frieze along the parapet (Ill. 76).

In 1930–1 Nicholsons extended the row on the south side of the street over the former Noah's Ark site. The new houses and the old No. 5 were destroyed by bombing in 1940, and replaced by Nicholsons in 1950–1 with the present Nos 5 and 6 (by Kenneth Lindy, Joseph Hill & Partners, architects). (fn. 30)

Nos 17 and 18, designed by W.H. Woodroffe & Son, were built to provide an additional warehouse and factory for John Groom's mission in 1922–3. The building occupies the site of a warehouse left unfinished by the builder James Whiting in 1843 but taken over soon afterwards by Alexander A. Croll & Co. as a gas-meter factory. Croll, former superintendent of the Chartered Gas Co.'s works in Brick Lane, had co-devised the first dry gas-meter using a flexible diaphragm, an invention which superseded the existing type of meter, using a wheel submerged in water. The dry meter was perfected by Thomas Glover of Leith, who took over the Croll factory, expanding it into the adjoining houses in Sekforde Street (Nos 44–46) before moving in the late 1860s to a new building in St John Street. (fn. 31)

Woodbridge Chapel

Woodbridge Chapel was built in 1832–3 for Independent High Calvinists. It seems to have been designed by an architect or surveyor named Thomas Porter, who was responsible for the adjoining schoolroom added in 1844–5. (fn. 32)

In 1894–5 the chapel, its congregation having dwindled away, was acquired by John Groom's mission, against competition from Nicholsons, who had been using the vaults for years as a liquor store. In 1897 this hitherto windowless cellar was converted for use as a school, lecture hall, dining-hall and flower-making workroom, the brick piers of the vaulting being replaced by iron columns. (fn. 33)

Towards the end of the Second World War the chapel was let to the Islington Medical Mission, which had been bombed out of its base in Britannia Row. Now called the Clerkenwell and Islington Medical Mission, this holds Sunday services and runs a National Health Service surgery in the old schoolrooms. (fn. 34)

The building is externally plain, with a modest classically treated entrance (Ill. 77). Internally, many of the fittings and furnishings may date from the 1890s refurbishment for the mission, although the gallery, carried on cast-iron columns with palmate capitals, seems to have been installed in the 1870s, when the number of sittings increased from 450 to 665. (fn. 35)

77. Woodbridge Chapel in 2006

St James's Walk (east side)

St James's Walk probably originated as one of the walks mentioned in Thomas Seckford's will. It was called Hart Alley by 1708 and later New Prison Walk, acquiring its present name in 1774. (fn. 36) The southernmost portion became part of Sekforde Street in 1937.

Nos 16–18 (and 1–7 Sekforde Street). This was erected in 1908–10 as the New Crippleage, a warehouse and factory for John Groom's Watercress and Flower Girls' Christian Mission (Ill. 78). The architect was W. H. Woodroffe, partner of E. Carrit, the Seckford Charity's surveyor, and the building contractor was John Greenwood Ltd. (fn. 37)

Over the main entrance was mounted a sculpture by W. Aumonier & Son, designed as 'an appreciation' of Groom's life's work. Now removed, this figurative group depicted 'Mercy tending the blind children' (Ill. 79). (fn. 38)

In 1912 the factory produced 13 million cotton roses for the first Alexandra Rose Day. (fn. 39) From the early 1930s until the 1950s, the building was occupied by the tobacco company Gallahers as warehousing and offices, and then by Mono Pumps Ltd of Manchester. In the early 1980s it was adapted as offices for Help the Aged, by the architects CZWG. (fn. 40)

78. John Groom's New Crippleage, St James's Walk, in 1914

79. New Crippleage: 'Mercy tending the blind children', by W. Aumonier & Son. Removed

No. 20, former Clerkenwell Parochial Sunday School. The school was founded in a house on this site in 1807, and the present building—with the master's rooms fronting the street—erected in 1828–9 to the design of William Lovell of Pentonville. The second floor was added in 1858 by W. P. Griffith. (fn. 41)

After the closure of the school in 1903, the building was taken over by John Groom in connection with his mission. Occupied from 1911 by Cambridge University Press, it remained in commercial use until 1987 and was made into a private dwelling in 1993–4. (fn. 42)

Nos 22A and 24 are of late eighteenth-century or early nineteenth-century date. They were taken on lease in 1828, at the start of the redevelopment of the Seckford estate, by the builder Charles Hellis, who erected workshops and stabling in the yard at the rear (No. 22). (fn. 43) Nos 26–32 are by the builder Henry Johnson; Nos 30 and 32 were finished in 1834, the others not until 1837. (fn. 44)

Sekforde Street

Sekforde Street was the most important of the streets laid out on the Seckford estate in the late 1820s and is the best preserved, retaining the majority of its original houses (Ills 80–82). These mostly date from ten or twelve years after the creation of the street, where house-building fell off after the failure of John Bewley's building activities. Bewley's own houses are the Sekforde Arms at No. 34, of 1828–9, and the three houses adjoining, Nos 35–37. These last were built in carcase at the same time as the pub but left unfinished for several years; they were completed by Henry Johnson, who built several other houses in the street. Besides Bewley, James Clack, a brickmaker, carried out some early building in Sekforde Street, and several other builders were involved in completing the street in the late 1830s and early 1840s.

From the start, Sekforde Street combined a residential with a commercial and industrial character. At the top end, the Finsbury Savings Bank looked straight across at William Oliver's mahogany warehouse, while Johnson ran his business from a yard in what had been the forecourt of Woodbridge House. No. 35 retains a shopfront probably dating from c. 1837, when the new house was leased to Robert Bunting, lapidary, previously of Red Lion (now Britton) Street. The glazing-bars are not original.

80. Nos 30–33 Sekforde Street, houses of 1838–42

With the notable exception of the mahogany warehouse site, redevelopment has largely been confined to the southern end of the street, where industrial buildings were erected at various dates from the early twentieth century. Blick House at Nos 44–46 was built on the site of bombed houses in 1963–4 for Blick Time Recorders Ltd. The architect was Robert Cromie, who had made his name in the 1930s designing cinemas. (fn. 45)

In 1983–5 former industrial premises at the rear of Nos 11–14, extending to Sans Walk, were remodelled as offices (London House and Yeoman House); the architects were the Bader Miller Davis Partnership. The entranceway on the north side of No. 11 was infilled at the same time, forming No. 11A. (fn. 46)

The residence of the missionary John Groom is commemorated by a Blue Plaque at No. 8.

81, 82. Sekforde Street in 1949: Nos 15–18 and (right) Nos 22 and 23

Sekforde Street development, c. 1828–42: summary of surviving buildings (fn. 47)

Nos 8, 9. 1839. Henry Freeman, builder

Nos 10–13. No. 13 begun 1830. Nos 10–12, 1838–40. Henry Johnson, builder

No. 14. Converted c. 1836 from part of Woodbridge House. Henry Johnson, builder

Nos 17, 18. 1839–40. Benjamin Slipper & Joseph Cornick, builders

No. 18½. 1839–41. Finsbury Savings Bank. Alfred Bartholomew, architect

No. 19. 1839–40. Charles Shore, builder

Nos 20, 21. 1838–9. Benjamin Slipper & Joseph Cornick, builders

Nos 22, 23. 1828–30. James Clack, builder

Nos 25, 26. Completed 1834. Henry Johnson, builder

Nos 26A and 27. 1839–40. William Hotten, builder. No. 26A built as workshop

Nos 28–31. 1838–40. William Hotten and Henry W. W. Hernage, builders

No. 32. 1838–9. William Wood, watch-jeweller, first lessee

No. 33. 1841–2. Built for J. & W. Nicholson, distillers

No. 34 (Sekforde Arms). 1828–9. John Bewley, builder

Nos 35–37. 1828–9. John Bewley, builder; completed by Henry Johnson, c. 1834

Nos 38–43. 1839–41. James Whiting, builder

No. 18½, former Finsbury Savings Bank

Intended for 'tradesmen, mechanics, labourers, servants, and others', Finsbury Savings Bank was founded in 1816, and by the 1820s was based in St John's Square. Almost from the start of the Seckford estate redevelopment, the managing committee had expressed interest in taking a plot for new premises, but it was 1839 before the site was agreed.

The building was designed by Alfred Bartholomew, son of a Clerkenwell watchmaker, and briefly, before his early death, one of the first editors of The Builder. It was to be his only significant architectural work.

Bartholomew soon settled the 'Style and substantial Character' of the bank with James Noble. Building began about the middle of May 1839, and the exterior was largely complete by the end of the year. However, a dispute between the committee and the contractor caused delays, and it was not until April 1841 that Noble found 'our Savings Bank in full operation'. (fn. 48) Charles Dickens was an early depositor of trust funds in October 1845. (fn. 49)

Bartholomew, who a few years earlier had put forward a design for a 'larger and superior' building, had wanted the bank to be faced in Portland stone, and built entirely on fireproof principles, a particular interest of his. However, the committee was not prepared to countenance these or other extravagances. (fn. 50) Probably the bank committee's regard for economy saved the building from decorative excess; the stuccoed Italianate façade was certainly less ornate than Bartholomew wanted, though he paid for some of the external decorations himself, rather than let the scheme suffer 'further mutilation'. The front part of the building is of two storeys, the rear (originally comprising various 'domestic apartments') of three. The end bays are set back and originally contained the public entrance and the manager's private entrance (to left and right respectively). Above these, the windows are framed by Egyptian-style pilasters with lotus-leaf capitals (Ill. 83).

83. Former Finsbury Savings Bank, No. 18½. Sekforde Street, elevation and detail of railings. Alfred Bartholomew, architect, 1839–41

Alterations were made in 1928, following the bank's absorption into the London Trustee Savings Bank. Steelframed windows were fitted, and two windows on the ground floor made into double doors in connection with considerable internal re-ordering. The small grilled firstfloor windows, to ventilate a lavatory and light a staircase, were added at this time. The architect was Cecil H. Perkins. (fn. 51)

Closed in the 1960s, the bank was converted first to offices, and then into one large dwelling in the mid-1990s. (fn. 52)

Mahogany warehouse (demolished)

Scott House, a small block of flats of 1983–4, occupies the site of a warehouse built in 1828 for William Oliver, mahogany and timber merchant, in the rear of his premises in St John Street. This was designed for him by the Seckford Estate's assistant surveyor James Noble, and was intended for the sale of mahogany. (fn. 53) The brick and stucco front, divided into three arched openings framed by giant pilasters with an entablature and blocking course, had a monumental treatment, leavened by some slight decorative work in relief (Ill. 84).

Oliver moved away after a few years, but his premises continued in the hands of timber merchants until the 1890s, later becoming a sheet-iron works. A listed building, the warehouse was negligently demolished in 1970 during the clearance of the St John Street part of the premises. (fn. 54)

84. Former mahogany warehouse, Sekforde Street, in 1943. James Noble, architect, 1828. Demolished

Skinner Street (south side)

The short stretch of Skinner Street dealt with here, between Woodbridge and St John Streets, was built up with houses in the late 1760s as Corporation Row. At that time, it was no more than the eastern half of a narrow lane separating the former St Mary's Close from the fields to the north, and continuing westwards as Corporation Lane along the north side of the New Prison. In 1778 Corporation Row was widened into a proper roadway with a footpath. (fn. 55)

Nos 35–45. These houses, originally Nos 1–7 Corporation Row, were built in 1768–9, probably by John Cole, bricklayer and builder, and Richard Hilton, carpenter and builder, both of Clerkenwell. (fn. 56) They are three windows wide, with side passages, and of three storeys, with basements and attics. As built the doorways were framed by Tuscan pilasters carrying a metope frieze and pediment; these features were lost during refurbishment in the 1950s or early 60s (Ills 85, 86). A single-storey extension to No. 45 became auction rooms and later a school, taking the number 47; it was probably demolished in the mid-1930s. (fn. 57)

No. 49, at the eastern corner with Woodbridge Street, was erected in 1836 by William Tooley, carpenter and builder, of nearby St James's Buildings, and was originally a butcher's shop. (fn. 58)

Woodbridge Street

Woodbridge Street in its present shape dates largely from the 1820s, when part of the existing Woodbridge Street, as Red Bull Yard had been renamed in 1778, was extended northwards to Corporation Row (Ills 5, 6). It was built up mostly with double- and single-fronted terrace houses in the 1820s–40s, though south of the crossing with Sekforde Street the frontage was largely taken up with the flank of Woodbridge Chapel and the back of Nicholsons' distillery. All the houses on the west side of the street north of the former Woodbridge House were demolished in 1870 for an extension to the House of Detention. The demolition included the building adjoining Woodbridge House, occupied from the late 1820s by Michael Gunston, chemist and 'sole proprietor' of Daffy's Elixir, the famous concoction of gin and senna invented by the Rev. Thomas Daffy in the seventeenth century. This may have originated as the house built by Thomas Seckford in the sixteenth century adjoining his own residence, Woodbridge House.

Woodbridge House itself, rebuilt twenty years before the main redevelopment of the Seckford estate began, is described below.

85. Nos 35–43 (left to right) Skinner Street in 1943

86. Nos 35–45 Skinner Street in 2004

For the rest, half a dozen of the original houses, dating from 1838–40, survive: Nos 14, 16 and 30–36 (Ill. 87). No. 14 was built by Benjamin Slipper and Joseph Cornick, Nos 30–34 by James Whiting, carpenter, all three being active also in the development of Sekforde Street; the builders of Nos 16 and 36 are not known. (fn. 59) No. 34 is doublefronted and has a semi-circular projection at the rear containing the staircase. The present Nos 12 and 18–28 are flats built for Islington Council in 1978–80, designed to blend in with the existing terraces (Pollard Thomas & Edwards, architects). Adjoining Woodbridge Chapel, at Nos 7–9, is a former artificial-flower factory built in 1908–9 for John Groom's mission (W. H. Woodroffe, architect). (fn. 60)

Woodbridge House

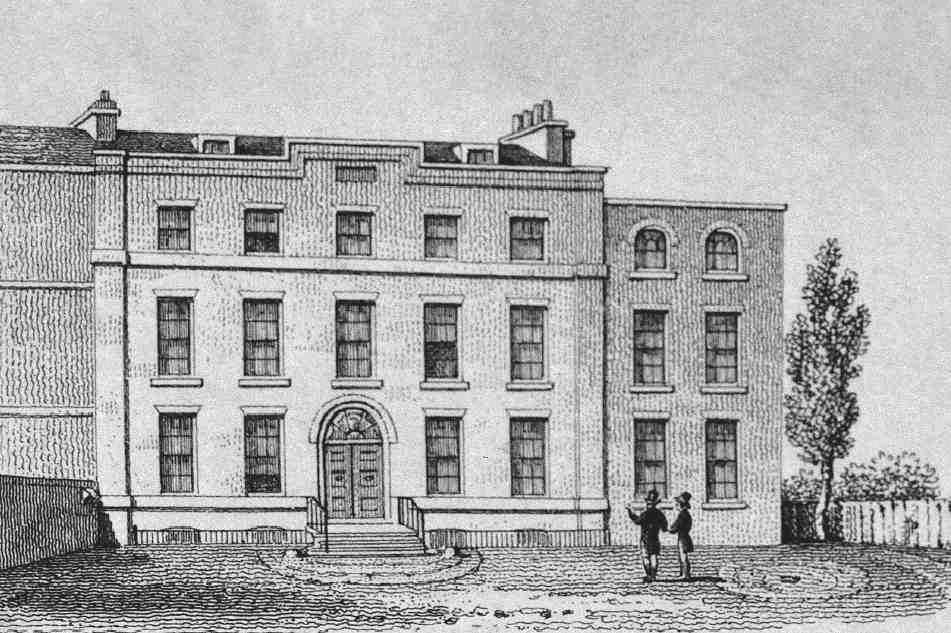

At the junction of Sans Walk and Woodbridge Street are three houses (Nos 11 and 13 Woodbridge Street, No. 14 Sekforde Street), built about 1808 as a single residence called Woodbridge House. (fn. 61) A rebuilding of the house of the same name erected by Thomas Seckford in the sixteenth century, it was built for William Cook, solicitor, long-serving Vestry clerk and clerk to the local paving commission, in anticipation of a new lease. Cook's plans went badly wrong. Having spent heavily, building on what proved to be shaky legal foundations, he ultimately lost the property. Instead of setting a superior tone for the estate redevelopment, Cook's creation proved a white elephant and after a period of neglect was ignominiously butchered to fit in with the emerging terraces of third-rate houses.

Cook had inherited old Woodbridge House, with a dyeworks and other buildings together occupying a substantial plot, from the former resident George Friend, scarlet-dyer to the East India Company, to whom the property had been leased in 1767. Estranged from his wife, and without children or close relatives, Friend died in 1807 leaving his whole fortune to Cook, whose office in what is now Sans Walk, a few yards away, formed part of Friend's leasehold.

87. Nos 14–22 Woodbridge Street in 2004

The 1767 lease, as was usual with the estate leases at that time, had been granted by the governors with the 'consent and good liking' of the minister, churchwardens and inhabitants of Woodbridge. (fn. 62) Though in fact this was little more than a legal formula, Cook seems misguidedly to have made a verbal agreement with the churchwardens for a renewal of his lease, which had twenty years to run, and on the strength of this began rebuilding Woodbridge House. Subsequently, however, the deal was upset by the minister and parishioners at a Vestry meeting, and the matter remained unresolved until the expiry of the lease was imminent, when Cook's attempts to negotiate a favourable settlement, taking into account his outlay, met with no success.

88. Woodbridge House, south-west front, c. 1828. James Spiller, architect, c. 1808

Cook also spent heavily on a summer residence at Enfield, and the Woodbridge House fiasco seems indeed to have been part of a general folie de grandeur engendered by his legacy, which brought him to near-ruin, ill-health and the Fleet debtors' prison—from which he emerged to expatriation in Belgium with his family. At the same time, Cook had devised an improvement scheme for his leasehold ground, if not the estate generally, including the formation of a new road from St James's Walk to St John Street. (Plans for this were drawn up for him by Thomas Hornor, whom he had commissioned in his capacity of Vestry clerk to carry out a survey of the entire parish.)

89. Nos 11–13 Woodbridge Street and 14 Sekforde Street (the former Woodbridge House), in 2004

Two decades on, with Cook's tenancy at an end and the estate redevelopment progressing but slowly, Woodbridge House suffered from theft and vandalism. James Noble, the assistant Sekforde Estate surveyor, was well aware that it would never let as a single residence, and in 1830–6 the builder Henry Johnson converted the main body of the house into two unequal houses, and the side wing into a third, reversing the building so that the back became the new fronts (Ill. 89). (fn. 63) The forecourt became his own yard, and for a time he used the name Woodbridge House for the part he occupied himself, which seems to have been the former wing (now No. 14 Sekforde Street). By the late 1840s No. 13 was used as a girls' school, while from then until 1870 No. 11 was occupied by the Finsbury Dispensary. (fn. 64) The flank of No. 13 was exposed with the demolition of the Daffy's Elixir warehouse and the opening up of Sans Walk into Woodbridge Street in the early 1870s, following the enlargement of the House of Detention site.

Cook's 'noble mansion' (fn. 65) was designed by James Spiller, architect of St John's Church, Hackney, and comprised a symmetrical five-bay block with a slightly lower two-bay wing to the south, facing west across a forecourt to a large coach-house and stable block (Ill. 88). The main façade survives substantially intact as the rear elevation of the present-day houses.