An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 1, West. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1952.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 1, West, (London, 1952) pp. xxxiii-l. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol1/xxxiii-l [accessed 20 April 2024]

In this section

SECTIONAL PREFACE

(i) EARTHWORKS ETC., PREHISTORIC AND LATER

The tracts of coastal downland and interior woodland, heath or parkland which comprise the county of Dorset can claim a measure of unity in pre-mediæval times, and may indeed be equated approximately with a pre-Roman tribal area. They are in any case sufficiently extensive to lend themselves to unitary treatment by the student of prehistoric and Roman antiquity. But no such claim can be made for the arbitrary segment of the county to which, for convenience of publication, the present volume is restricted. No attempt is therefore made here to assess the county's material contribution to our picture of Roman and pre-Roman Britain: that attempt must await the completion of the inventory in the last of the three Dorset volumes, when the evidence will be reviewed as a whole. Meanwhile, it may be convenient to indicate without comment the general range of the prehistoric and Roman sites described in the following pages.

Within the area covered by the present volume the earliest prehistoric monuments are the collective tombs of the Neolithic period (with a central date of c. 2000 B.C.). "The Grey Mare and Her Colts" at Long Bredy is a megalithic chambered tomb in a long cairn, with shallow forecourt, having analogies on the West British seaboard, while the more common type of long barrow, represented also at Long Bredy and at Bradford Peverell, belongs to the Wessex "unchambered" group in which stone burial-chambers are absent. "Bank-barrows" comparable with that excavated at Maiden Castle exist in the same two parishes and at Kingston Russell.

The Bronze Age is represented by notable groups of round barrows, such as those at Abbotsbury, Askerswell, Bradford Peverell, Little and Long Bredy, Cerne Abbas, Frampton, Kingston Russell, Stratton, and Sydling St. Nicholas, and by many isolated examples elsewhere. The chronological range is from c. 1800 to 800 B.C., but the specialised types of bell, disc and pond barrows have a distribution almost entirely restricted to Dorset and Wiltshire and are characteristic products of the brilliant Wessex Culture of the Middle Bronze Age, c. 1550–1300 B.C., having strong links with the Continent. Stone circles, such as that at Kingston Russell, also probably belong to the earlier part of the Bronze Age.

With the Early Iron Age (from c. 350 B.C. to the Roman Conquest) appear the first hillforts, the simpler forms with single rampart-and-ditch construction probably in the main dating from the early part of the period (3rd-2nd centuries B.C.). In the first century B.C. changes in war-technique introduced by immigrants from West France produced multiple-rampart defences in depth, frequently added to earlier forts, as at Abbotsbury and Pilsdon.

Undefended settlement-sites, with earthwork-enclosures and storage-pits, often associated with cultivation-areas, are common and are most probably largely of Early Iron Age date, though many may well extend into the Roman period. The field-systems are normally of oblong fields distinguishable from the narrow strips of mediæval type. Examples exist at Cerne Abbas, Little Bredy, Cattistock, Up Cerne, Compton Abbas, Compton Valence, Frampton, Maiden Newton, Sydling St. Nicholas, Stratton and Wynford Eagle.

Some Enclosures and Other Minor Earthworks

The turf-cutting, the Cerne Giant, is probably of the Romano-British period and with it may well be associated the small rectangular enclosure above the head of the figure.

Reference should also be made to the very slight hill-top earthwork of oval form called the Old Warren, Little Bredy (4). This has some claims to represent the Burgh at "Brydian" of Alfred's time, recorded hereabouts in the Burghal Hidage.

The later mediæval earthworks are not of outstanding importance. The castle-site at Sherborne (Castleton) is of oval form defended where necessary by a ditch. There are furthermore two, perhaps successive, mount and bailey earthworks at East Chelborough and a mount and rectangular bailey at Marshwood. The somewhat enigmatic earthworks just E. of the abbeysite at Cerne are presumably post-Reformation.

The mediæval open-field system involving the allocation of fields by narrow strips has left traces on hill-slopes in the form of strip-lynchets, which may be of any age up to the Enclosure Acts, and are visible at Abbotsbury, Beaminster, Bothenhampton, Long Bredy, Burton Bradstock, Compton Abbas, Compton Valence, Corscombe, Frampton, Kingston Russell, Loders, Maiden Newton, Netherbury, Powerstock, Sydling St. Nicholas, and elsewhere.

(ii) ROMAN REMAINS

The area surveyed in the present volume excludes the Roman sites at Dorchester, but includes recorded buildings at Bradford Abbas, Castleton, Halstock, Maiden Newton (the "Frampton villa" with Chi-Rho monogram), Rampisham, Sherborne and Thornford. The Bradford Abbas site included kilns. In no case has any extensive exploration of a scientific kind been carried out. It is probable that the turf-cut "Cerne Giant" should be equated with Hercules and be regarded as Romano-British work.

(iii) ECCLESIASTICAL AND SECULAR ARCHITECTURE

Building Materials

The building materials in W. Dorset are almost exclusively local. The building stone comes from three main strata: (a) Ham Hill stone (over the border in Somersetshire) of the Upper Lias, (b) Calne, Marnhull and Todbere stones of the Corallian and (c) Portland stone. Of these the Ham Hill stone is used in all the better class work in the N.W. part of the county while Portland stone is sparingly used in the S. part of the district in work of the later periods. Other local materials are the Forest marble of the N. and the Purbeck marble of the S.E. Both these are used for decorative shafting, effigies, etc. In the chalk district round Dorchester considerable use is made of flint for rubble-walling. The lias is also employed for rubble-work and paving. Brick hardly makes its appearance before the 17th century and is very sparingly used until the 18th century.

Timber-framing is an occasional method of building, most usual in the towns such as Sherborne and Cerne Abbas; this use dates back to the 15th century but no instances have been found of earlier date. Cob is scarcely used except in the S.W. corner of the area, and, even there, Symondsbury and Wootton Fitzpaine are exceptional in having so high a proportion as four in ten cottages cob-built. The normal roofing of the district is thatch and a high proportion of rural buildings are still covered with this material. An examination of the secular monuments scheduled in such parishes as Powerstock and Thorncombe shows that 54% and 67% respectively are still thatched. In the towns and for the larger houses stone slates were no doubt the early roofing material.

Ecclesiastical Buildings

The only structural remains of the pre-Conquest period are to be found in the present W. wall and possibly in the central crossing of the abbey-church of Sherborne; they include the existing N.W. doorway and an uncertain amount of the rubble walling of the front and perhaps the core of the cylindrical piers of the crossing. The doorway has a strip-framework cut away at the head and may be assigned to the 10th century. The form of the early church at Sherborne is considered in a separate section of the preface, see p. xlvii. Of the isolated remains of the same period by far the most important is the cylinder carved with beasts which, now reversed, serves as the font at Melbury Bubb; it seems probable that it was originally a section of a cross-shaft. The neighbouring church at Melbury Osmond has a slab with carved interlacing decoration including a frog-like beast which can be paralleled on the shaft from Closeburn, Dumfriesshire. At Yetminster is part of a cross-shaft of unusual form and with nimbed busts under arches on the two surviving faces; the workmanship is inferior. There is a fragment with interlacement built into a buttress at Batcombe. These four may perhaps be dated to the 10th century. To the first half of the 11th century probably belong the fragments at Toller Fratrum and Cattistock. The former is part of a figure-subject of the Magdalen washing the feet of Christ; the head of the Magdalen and the feet of Christ survive and form a strongly characterised example of late Anglo-Saxon sculpture. The fragment at Cattistock is part of the head of a cross with foliage, interlacement and rosettes. At Whitchurch Canonicorum is a stone with two circular designs of doubtful date and purpose but used as material in a late 12th-century wall. Finally mention may be made of the monolithic Cross and Hand, Batcombe, a cylindrical shaft with a capital of crude cubical form, which may be related to the pre-Conquest series with tapering capitals.

The Romanesque period is not well represented in W. Dorset save in parts of the Abbey and the old Castle at Sherborne. The abbey was rebuilt at the time, and probably under the impulse, of Bishop Roger of Salisbury who rebuilt the Castle. It had a square-ended presbytery probably extending one bay beyond the aisles. Parts of the central tower, transepts, side chapels and the reconstructed S. porch survive of this period.

Remains were found of an apsidal chancel at Cattistock when the church was largely rebuilt. Lyme Regis and Maiden Newton have towers, in part of the 12th century, which were formerly central in an aisleless church. The best surviving example of 12th-century work in the district is, however, the rather elaborate and distorted chancel-arch at Powerstock; the responds of a chancel-arch of the same period remain at Godmanstone. The S. arcade at Whitchurch Canonicorum and the S. arcade at Broadwindsor are 12th-century work, as are the chancel-arch at Puncknowle and the N. doorway at Poyntington. The chapter-house at Forde and the chancel at Loders have both the curious feature that the vaulting-responds are set back in a recess in the wall. Mention should be made of the rich carved detail of this period built into the walls at Abbotsbury Abbey House and Maiden Newton church.

The 13th century is best represented by the remains of the Lady Chapel at Sherborne, the N. arcade and transepts at Whitchurch Canonicorum, the transepts at Bridport and the chancel at Long Bredy. Bridport, South Perrott and Wootton Fitzpaine are 13th-century cruciform churches with central towers though the tower and crossing at Bridport were rebuilt c. 1400; 14th and 15th-century examples of the cruciform series may be found at Symondsbury, Burton Bradstock and Melbury Sampford.

The work of the first half of the 14th century is neither extensive nor important but the tower and spire at Trent should be mentioned. To the second half of the century belongs the remarkable stone-vaulted chapel of St. Catherine at Abbotsbury. With the later part of the 14th century begins a long series of works largely produced to standard pattern over a period of a century and a half and consequently very difficult to date except with the assistance of documentary evidence. This standard production is probably due to the predominance of the Ham Hill quarries during the period. The finest work of the age is the rebuilding of the abbey of Sherborne which was undertaken in two main campaigns; the richly-coloured stone is from Ham Hill and the elaborate stone vaulting extends through most of the church. The parish churches provide a series of towers, of which those at Beaminster, Cerne Abbas, Whit-church Canonicorum and Bradford Abbas are the most remarkable. The S. chapel at Bradford Abbas and the S. chapel and aisle at Loders should also be noticed.

Post-Reformation church building in W. Dorset is not of great importance though it includes two complete buildings of considerable interest, the parish church at Folke, 1628, and the chapel at Leweston, 1616; both these are buildings of Tudor Gothic character, Folke having a N. arcade of curious detail. The N. chapel at Minterne Magna (c. 1610–20) is of similar character. The tower at W. Chelborough was built in 1638 and that at Frampton in 1695; the latter is highly unusual, the place of buttresses being taken by superimposed and engaged Tuscan columns, the tower being finished with an embattled parapet and pinnacles. The church at Castleton (Sherborne) was rebuilt by William, 5th Lord Digby, and consecrated in 1715; it is referred to by Pope as a "neat little chapel" which Lord Digby told him "was of his own architecture". Later 18th-century work is best represented by the N. chapel at Seaborough (1729) with a Gothic window and Melbury Osmond which was largely rebuilt in 1745 and is a simple Renaissance structure. The later additions to Over Compton and the tower at Minterne Magna (c. 1800) may also be noted.

The 19th-century churches are of interest and show a wide choice of styles. Fleet (1827–9) is in Gothic deriving from the 18th-century Revival, and the treatment of the interior of the chancel has considerable delicacy and decorative effect. Allington (1827), a neo-Greek building, has a robust Doric portico. At Compton Valence (1839) the use of Gothic is largely traditional whereas at Monckton Wyld, in Wootton Fitzpaine, (1848) and Bradford Peverell (1850) it is a conscious revival of 13th and 14th-century styles. Melplash, in Netherbury, (1846) is entirely in 12th-century style and is a remarkable example of studied antiquarianism.

Nonconformist churches are represented by the "Friends" Meeting House at Bridport, a 17th-century building, and by three later buildings of some distinction; the first is the mid 18th-century Congregational Chapel at Lyme Regis (1755), the second the Unitarian Chapel at Bridport (1794) and the third the Methodist Chapel at Bridport, a neo-Greek design of 1839 with symmetrical wings.

Monastic and Collegiate Buildings

The district covered by this volume includes three great Benedictine abbeys and a Cistercian abbey. The three Benedictine houses are Sherborne, Abbotsbury and Cerne. Of the first the abbey-church survives almost intact and there are some remains of the monastic buildings. The abbey-church at Abbotsbury has been destroyed except for a small part of the base of the N. wall of the nave; the great barn, some subsidiary buildings and parts of two gatehouses are still standing. The abbey of Cerne has been even more completely demolished and the remains are now reduced to the porch of the abbot's house, a subsidiary building and a barn. The church and part of the cloister of the Cistercian abbey of Forde have been destroyed but much of the monastic buildings and the abbot's house are still standing. Large parts of these including the N. walk of the cloister and the great hall of the abbot's lodging were rebuilt by the last abbot, Thomas Chard, on an extensive and elaborate scale; the decoration includes much carving of early French Renaissance character. Of the minor monastic houses the parish church of Loders formerly served the alien priory there and there are some small remains of the hospital of St. John the Baptist at Bridport.

The Almshouses at Sherborne are an interesting survival of a 15th-century hospital planned on two storeys with a chapel the full height of the building. There is a small almshouse at Beaminster founded by Sir John Strode in 1630, and the 19th-century almshouses at Trent (1846), formally planned on two sides of a small courtyard and built in traditional style, are of scenic merit.

The school at Sherborne retains its old School-house rebuilt in 1670; the original headmaster's house was contrived in the eastern chapels of the abbey-church. Trent has the school-house of John Young's school, founded in 1678, and Yetminster that of the Hon. Robert Boyle, founded in 1691.

Secular Buildings

Sherborne Old Castle (Castleton) is alike the most important military and early domestic building in W. Dorset. It was built by Roger, Bishop of Salisbury, in the 12th century and the main central building with its inner courtyard, four ranges and a keep is amongst the most important examples of 12th-century military-domestic work in this country. There are some remains of a tower on the motte of the Mandeville castle at Marshwood and the shell of a defensive tower at Holditch Court, Thorncombe. The only other building with some claims to be defensive is the 14th or 15th-century house called the Chantry at Bridport. It is a square structure of the isolated tower-house type.

Pickett Farm South Perrott

The Queen's Arms ~ Charmouth

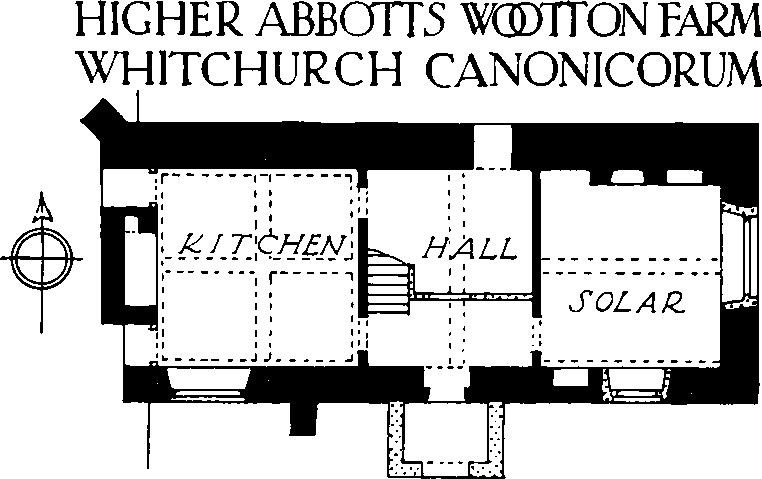

Higher Abbotts Wootton Farm Whitchurch Canonicorum

Toller Whelme Manor House Corscombe

With the exception of a 12th-century doorway at Hummer Farm, Trent, which may well have come from elsewhere, the earliest domestic buildings of the district date from the latter part of the 14th and the early part of the 15th century. Of these Church Farm, Trent, and the Court House at Poyntington may be mentioned; the former retains the three original doorways at the back of the screens. The 15th century provides three examples of a somewhat unusual type of house comprised in a long rectangle of two storeys with diagonal buttresses at one end. These houses are Toller Whelme Manor House, Corscombe, Pickett Farm, South Perrott, and Higher Abbots Wootton, Whitchurch Canonicorum. There is no great certainty about the original internal arrangement of these three buildings but the third seems to have had three rooms on the ground floor of which the western perhaps represented the solar; the original entrance doorway gives access to the middle room. A far more complete building of the same type is the Queen's Arms Hotel at Charmouth, which retains all the evidence of the original internal arrangement; it had a hall with a withdrawing-room at one end and screens, buttery, pantry and kitchen at the other end. Work of the 15th century is represented by the well-preserved porch and the adjoining wing at Childhay, Broadwindsor, by the hall-block at Upbury Farm, Yetminster, and by the Chantry at Trent and Poyntington Manor House, both of c. 1500; Berwick, Swyre, has been much altered but the hall and screens arrangement survives, and the screens-passage retains work of the early years of the following century. To the first half or middle of the 16th century belong a series of important houses with late Gothic details; most of these have the distinctive feature of octagonal or circular shafts at the main angles of the building carried up as pinnacles above the parapets. Perhaps the earliest is the courtyard house at Melbury, with its remarkable tower, built by Sir Giles Strangways before Leland's visit about 1540. Of the same type is the once splendid house at Clifton Maybank, the original wing at Mapperton and Little Toller Farm, Toller Fratrum. To the same period belongs the very complete house at Sandford Orcas with its gatehouse and the large but much altered house at Parnham, Beaminster. Timber building of the same age is represented by the long range of buildings on the W. side of Church Street, Cerne Abbas, now partly demolished. The new castle at Sherborne (Castleton) was built by Sir Walter Raleigh c. 1595 on a rectangular plan with turrets at the angles; the addition of the four wings in 1625 has produced a somewhat remarkable plan, but the house has been much altered and restored. A number of important houses were built or largely rebuilt in the first half of the 17th century; these include Mapperton, Chantmarle (Cattistock), Melplash (Netherbury) and Up Cerne Manor House; amongst the smaller manor houses Hooke Court, Mappercombe, Powerstock, Rampisham, Wraxall, Wynford Eagle, Folke, West Hall (Folke), Melbury Bubb and Wyke (Castleton) may be mentioned. To the middle of the century belong the important alterations at Forde Abbey with their elaborate plaster ceilings. Good examples of the last quarter of the century can be seen in the later work at Melbury House, at Mapperton Stables and Rectory, and Look Farm, Puncknowle. Kingston Russell House was rebuilt late in the 17th century but its façade is a reconstruction of the first quarter of the 18th century. The simple but effective façade of Lord Digby's School at Sherborne is a work of about 1720. This building, containing paintings attributed to Thornhill, is of some importance, for the rest of the 18th-century Renaissance is not very well represented in the district. Of the work of this century the town-hall at Bridport (1786) is the only civic building of note; William Tyler, R.A., was the architect. Bridport is an attractive market-town with a broad main street and a general appearance of the later part of the century; many Palladian windows survive and the feature was evidently a popular one in the vicinity. Bettiscombe Manor (c. 1710) remains remarkably little altered and, with the Red House, Sherborne (17th century and c. 1730), exemplifies country building of quality. The slate-hung front and the interior plasterwork of Wootton House in Wootton Fitzpaine (c. 1765) have affinities with West country work, which may be explained by the building owner's family connection with Devon. At Sadborow in Thorncombe (1773–5) professional advice must have been obtained, for the house is in the latest fashion of the time; the building accounts include the cost of sending letters to Bath and London. The front of the Greenhouse (1779) at Sherborne Castle (Castleton) is perhaps the most important classical elevation in the area surveyed. Among the buildings of the later 18th century are Downe Hall in Bridport (1789), much altered, East House, Sydling St. Nicholas, and the remarkable house, Belmont, in Lyme Regis (c. 1785) built for Miss Coade and crusted with Coade stone ornament from her artificial-stone works at Lambeth. The porch at Frome House (1782) is urbane and finely wrought.

Three examples of 18th-century Gothic are included in the Inventory; these are the Turret in the gardens of Melbury House mentioned by Walpole in the account of his visit there in 1762, the library at Sherborne Castle (Castleton) and, of less importance, the front of the Dairy at the same place.

Among the secular works of the 19th century the additions to Parnham in Beaminster (c. 1810) by John Nash are a notable example of his designing in romantic style. In Bridport, Charmouth and Lyme Regis are numbers of stucco-fronted villas of considerable charm, many retaining their original treillages; at the Cedars, a house of similar type in Sherborne, there is much refinement in the classical decorative features of the street-front.

Several shop-fronts are worthy of notice, one in Bridport, opposite the town-hall, of the end of the 18th century, and others of the early 19th century in Cerne Abbas, Beaminster, Sherborne and an unusual one in Lyme Regis.

The large stone barn forms an important architectural feature of the district. The largest is the great structure of twenty-three bays and 272 ft. long at Abbotsbury Abbey; it was built about 1400 and may be compared with the great Cistercian barns at St. Leonard's near Beaulieu (Hants) 216 ft. long and at Great Coxwell (Berks). The corresponding barn at Cerne Abbas has been reduced to nine bays and partly converted into a house. Another large barn at Wyke, Castleton, is 230 ft. long and the seven-bay building at Oborne may also be mentioned.

The earlier bridges of the district are mostly featureless. There are two bridges under the same road at Lyme Regis; the main one is a ribbed structure of the 14th century but the arch further E., now enclosed in buildings, is probably of early 13th-century date. The late 18th-century bridges at Frampton and at Pinford (Castleton) are notable.

Fittings

Altars: There are mediæval altar-slabs with consecration-crosses at Frome St. Quintin and Whitchurch Canonicorum and a few slabs have been noted elsewhere which may have served the same purpose.

Bells: West Dorset has retained as many as forty mediæval bells. Of these, eight bear dedications to Christ, fourteen to St. Mary, one to Christ, St. Mary and St. John, three to St. Gabriel, two to St. Augustine, two to St. Michael and one each to St. Mary Magdalene, St. Anne, St. Elizabeth, St. Margaret, St. Andrew and St. Lawrence. The earliest are the 14th-century 2nd at Trent, probably from a London foundry, the sanctus at Sherborne from the Bristol foundry and the bell at Wraxall cast by Thomas Hey, c. 1350–60, with his signature. Of the end of the century are the 1st at Trent, the 1st at Batcombe, the 1st and 2nd at Chetnole (London foundry) and the 5th at Little Bredy by John Barber of Salisbury. To the Salisbury foundry may be ascribed a dozen later mediæval bells, while the Exeter, Bristol, London and Reading foundries also contributed to a less degree. Of the later 16th century there is a bell dated 1563 at Hooke, with the initials W.P.; others come in all probability from the foundry of William Purdue of Closeworth. A local founder, William Warre of Yetminster, is responsible for a number in the late 16th and early 17th century. To the same period belongs the work of Robert Wiseman of Montacute and his sons, John Walter of Salisbury (1581–1624), John Danton of Salisbury (1624–40) and John Lott of Warminster. By far the greatest number of the 17th-century bells come however from the foundries of the various later members of the Purdue family: Roger Purdue I (1601–40), Roger Purdue II (1649–88), George Purdue of Taunton (1599–1633), William Purdue II (1637–69) and Thomas Purdue (1647–1704). Later foundries represented in the district include Lewis Cockey of Bristol and Frome, William Knight and Thomas Roskelly and the Bilbies of Chewstoke and Cullompton.

Brasses: The brasses of W. Dorset are few in number and comparatively unimportant. The best is the large figure in civilian costume of Sir Thomas Brook, 1419–20, and his wife, at Thorncombe. The figure of Sir Giles Strangways, 1562, at Melbury Sampford, is represented in armour with a tabard. There are early 16th-century figures at Rampisham and Yetminster. Figures of priests survive at Compton Valence and Evershot. Two of the inscriptions at Litton Cheney are palimpsest, the reverse bearing an earlier inscription, and part of the 18th-century inscription (4) at Cerne Abbas is in black-letter. There is the indent of a highly remarkable brass now cut in two and mutilated, the two parts being preserved at Askerswell and Whitchurch Canonicorum; it was formerly at Abbotsbury Abbey and commemorates Thomas de Luda, c. 1320, and his wife; it had two foliated crosses side by side and an inscription in separate capitals.

Candelabra: Five churches in the area contain candelabra. The earliest, in Sherborne Abbey, was given in 1657 and probably came from the Netherlands, another was given in 1714 to Castleton and may well be of English make. The remainder are of later date; one at Abbotsbury of c. 1760 has a vase-shaped body and is unusual in having repoussé decoration on the grease-pans; another undated example, at Cerne Abbas, has a flame finial issuing from a classical vase and probably dates from the third quarter of the century; Wynford Eagle contains a pair.

Chests: The chests of the district are of no great interest but there is a dug-out chest at Bradford Abbas and a heavy chest of hutch-type at Sydling St. Nicholas. Amongst the later chests the example at Trent is dated 1629.

Clocks: The works of four old clocks have been noted; that at Sydling St. Nicholas is dated 1593 and that at Yetminster nearly a century later in 1682. The third clock at Long Burton is of the 16th or 17th century and the fourth in Sherborne Abbey is probably of the 18th century.

Communion Tables and Rails: The best table is the early 17th-century example with carved and bulbous legs at Thorncombe; there is an enriched example with ordinary turned legs and dated 1638 at Cerne Abbas. The best communion rails are those at Folke, Burton Bradstock and Litton Cheney; those at Burton Bradstock are dated 1686.

Consecration Crosses: Seven churches in the area have series of consecration crosses; they are all probably of the 15th century and consist of formy crosses in circles cut in stone. Holnest and Thornford retain fourteen crosses each, Beer Hackett thirteen, Yetminster ten, Nether Compton nine, Minterne Magna six and Lillington five. Many of these crosses are not in situ.

Crosses, Churchyard and Wayside: The crosses of this type are fairly numerous in W. Dorset and include several with the weathered remains of figures cut in relief on one or more faces of the shaft. Among these are the cross in the main street at Maiden Newton (3), at Leigh (2), at Rampisham (3) and the churchyard cross at Bradford Abbas. The churchyard cross at Rampisham has an elaborately carved and inscribed base but unfortunately several of the carvings are not certainly identifiable and the inscription is not altogether legible; a cross-base of similar design is preserved in the museum at Sherborne Castle (Castleton). All the above crosses date presumably from the 15th or early 16th century, but there are a number of simpler and earlier examples, including the unusual cylindrical shaft called Cross and Hand at Batcombe (2).

Doors: Few of the doors in the district are of any particular interest; there are however doors with traceried heads at Trent church and at Church Farm, Trent, of late 14th or early 15th-century date and a panelled early 16th-century door at Parnham, Beaminster. The late 17th-century door in the tower at Puncknowle has the initials of Robert Napper in nail-heads. Three houses have panelled internal enclosures or lobbies with doors of the first half of the 17th century; they are Sherborne Castle (Castleton), Sandford Orcas and Chantmarle (Cattistock).

Fireplaces and Overmantels: The ordinary fireplaces of the district follow a form which did not greatly alter for two centuries. From the 15th to well on in the 17th century and perhaps later, the stone fireplaces have flat four-centred heads set in a square outer order with or without decoration in the spandrels. A few late mediaeval fireplaces of more decorative character survive; these may be seen at Abbey Farm, Cerne Abbas, the Chantry, Trent, and Hooke Court and have a frieze of quatre-foiled panelling above the opening with carvings including the initials of Abbot John Vanne at Cerne and the arms of Paulet at Hooke Court. There is a 17th-century stone fireplace with diminishing pilasters and a heavy entablature at Sherborne Castle (Castleton).

At Mapperton are two overmantels with enriched plasterwork of mid 16th-century date, and in the same house is a third plaster overmantel with the Paulet arms with pantheon supporters brought from Melplash (Netherbury) and dated 1604. The overmantels with the Digby arms at Sherborne Castle (Castleton) have been painted and restored but presumably date from early in the 17th century. Other carved overmantels of the same period are to be seen at Parnham (Beaminster), Up Cerne Manor House, Manor Farm (Wynford Eagle), Stratton Manor House, and the Conservative Club (13) and the Priory (41) at Sherborne; the first has a figure-subject of Joseph and Potiphar's wife and the second has figures of Adam and Eve and the serpent. There are late 17th-century fireplaces and overmantels at Forde Abbey and early 18th-century ones at Melbury House. Simply panelled overmantels at Bettiscombe Manor House may also be mentioned.

The remaining 18th-century fireplace-surrounds in the area are not of particular importance excepting perhaps one in the Manor House, Beaminster, carved with scenes from the Siege of Troy; there are two of marble with coloured inlays at 74 East Street, Bridport, and Sadborow in Thorncombe. Others of c. 1760 with carved rococo decoration are at Farrs, Beaminster, and in Wootton House, Wootton Fitzpaine; one at Wootton is unusual in the combination of carving in wood mounted upon polished touch.

Fonts: The most remarkable font of any period in W. Dorset is undoubtedly the carved cylinder at Melbury Bubb; there is little doubt that it formed a section of a late pre-Conquest cross-shaft which was converted into a font at some subsequent period; why the carved animals, forming the decoration, were reversed when this adaptation took place it is impossible to say, but perhaps the whole cylinder was plastered to a fair face and painted. To the post-Conquest period belong, firstly a series of plain or crudely ornamented tub-shaped bowls such as those at Burstock, Goathill and Poyntington and circular bowls of equally primitive character at Sydling St. Nicholas and Puncknowle. Of less determinate character are the fonts at Toller Porcorum and Batcombe; the former is reminiscent of a debased Roman capital with a ram's head at one angle and volutes at the other three; the Batcombe font has an equally unusual volute capital to the stem and a bowl in the form of a mortar with lugs and cable ornament at the angles. Of more normal 12th-century type are the carved fonts at Toller Fratrum and Stoke Abbott; the former has a series of crude figures under a broad band of interlacement and the latter has a richly diapered surface with a series of heads under arches at the top. Square or octagonal Purbeck marble bowls of rather later date survive at Loders, Netherbury, Up Cerne, Broadwindsor and Shipton Gorge. There are round arcaded bowls at Askerswell and Whit-church Canonicorum and a crudely but elaborately ornamented tub at West Chelborough. Simple 13th-century fonts survive at Powerstock, Leweston and South Perrott. The finest of the later mediaeval fonts is the carved and panelled example with figures at Bradford Abbas; the others of this period are of no great distinction. At Folke there is an enriched Jacobean font and at Castleton an early 18th-century font with a baluster-stem.

Glass: The earliest glass in the district is the series of 14th-century shields-of-arms at Cerne Abbas and there is much heraldic glass of the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries at Beer Hackett, Sherborne, Melbury Sampford, Mapperton and Parnham (Beaminster). Figures of the 15th century are represented at Sherborne Hospital and Melbury Bubb; at the hospital one window has figures of the Virgin and Child, St. John the Baptist and St. John the Evangelist. The Melbury Bubb glass is of more iconographical interest; the N.W. window of the nave has part of a figure of Christ showing the five wounds from which rays were carried to panels of the seven sacraments; one only of these, Orders, survives; in the tracery are unusual figures of the wise and foolish virgins. In the W. window are the Apostles, symbols of the Evangelists, the Persons of the Trinity, etc.; elsewhere in the Church is an Annunciation and some heraldry. At Loders a window in the S. chapel has figures in the tracery of St. Barbara, St. Dorothy, two ecclesiastics, etc. Some glass at Bradford Peverell, including a 16th-century shield of William of Wykeham, is said to have come from New College, Oxford. There is a large collection of foreign glass at Trent church and vicarage and smaller collections at Sandford Orcas, Parnham (Beaminster) and elsewhere.

Many churches in the area contain 19th-century glass. There are windows at Lyme Regis and Netherbury by Wailes, and an extensive scheme of reglazing carried through at Trent between 1842 and 1849 is perhaps also by Wailes. T. Willement in 1839 designed three lights for the E. window at Melbury Sampford and they are probably the ones incorporating older material now in the south window of the S. transept. The great Te Deum window in Sherborne Abbey was designed by A.W. Pugin for the 2nd Earl Digby and erected shortly after the middle of the century.

Helmets and Armour: The great tilting-helm at Melbury Sampford of the second half of the 15th century is by far the most important example of armour in W. Dorset and one of the most important in the country ; with it is a sword of the same age. In the same church are also a late 16th-century close-helmet, a 17th-century "pot" head-piece and two 17th-century swords. At Puncknowle is an early 17th-century helmet with gauntlets and a spur and at Forde Abbey, Thorncombe, is a late 16th-century helmet of a type associated with the Greenwich workshops with 17th-century gorget-plates. The late 16th-century close-helmet at Trent has traces of etched decoration on the ventail and the edges of the plates are invected.

Images: The churches of W. Dorset possess a considerable amount of architectural imagery dating almost entirely from the 15th century. The most extensive display is on the tower of Beaminster church and work of the same character survives on the towers of Cerne Abbas and Bradford Abbas. Small carved subjects, mostly Crucifixions, are to be found at Abbotsbury, Askerswell, Bridport, Frampton, Loders and Sherborne Abbey.

Monuments: The monuments of the district include thirteen mediaeval effigies. Of these the earliest is the upper part of the figure of Abbot Clement at Sherborne which can be nearly dated to c. 1160; a crudely carved figure of an abbot at Abbotsbury may be assigned to c. 1200. There are 13th-century figures of another abbot and a priest at Sherborne and a figure of an abbot of Cerne of the same period is now in the Farnham Museum. Effigies of cross-legged men in mail armour of the 13th century are to be found at Bridport (considerably restored) and at Seaborough (well under life-size). There are three 14th-century effigies at Trent, one a priest, one a man in civil costume and one a man in armour of c. 1380; at Poyntington is another figure in armour of about the same period but badly mutilated. The two canopied 15th-century tombs at Melbury Sampford both have well-preserved armed effigies of members of the Brouning family, though one tomb has been later appropriated by Sir Giles Strangways, 1547; at Netherbury is a canopied tomb with an effigy to a member of the More family, of c. 1480, in armour with the SS collar. One other mediaeval memorial, of the highest interest, is the 13th-century shrine of St. Wite at Whitchurch Canonicorum; the solid base has three recesses in which the pilgrims inserted the afflicted parts of their bodies.

To the later Tudor period belong the fine canopied monument with effigies of Sir John Horsey, father and son, c. 1565, at Sherborne Abbey, the tomb and effigy ascribed to Sir John Arundel, c. 1550, at Chideock and the canopied monument with effigies to John Leweston, 1584, at Sherborne Abbey. The finest monuments of the early Stuart period are those of Sir John Jefferey, 1611, at Whitchurch Canonicorum, to Thomas Winston, 1609–10, and Sir John Fitzjames, 1625, at Long Burton and to Sir John Browne, 1627, at Frampton, all with recumbent effigies. Amongst the smaller monuments of the period may be mentioned those to John Whetcombe, 1635, at Maiden Newton, a figure in a shroud to Joane Coker, 1653, at Frampton, to William Knoyle, 1607–8, at Sandford Orcas, to a member of the Keymer family at West Chelborough and to George Tilly at Poyntington. The monument to Ann Gerard, 1633, at Trent, is unusual in including an elaborate painted family-tree on the arch above. The later Stuart period is represented by a number of handsome monuments and many smaller memorials and tablets. The finest is the elaborate memorial to John, Lord Bristol, 1698, at Sherborne; this monument is signed by John Nost, a sculptor who worked at Hampton Court; possibly to the same sculptor belongs the monument to Thomas Strode, 1698–9, at Beaminster. Another handsome monument, by Robert Taylor, at Minterne Magna, commemorates Sir Nathaniel Napier, 1708, and the same church contains a number of good tablets of the same period. The monument to Sir Robert Napper, 1700, at Puncknowle, is signed John Hamilton.

The monument to Richard Brodrepp, 1737, at Mapperton is by P. Scheemakers and the later Strode monument, 1753, at Beaminster is undoubtedly by him. Other good 18th-century works are at Bradford Abbas and Over Compton and at Frampton where the memorial to Ann Browne, 1714, has a portrait-bust of great charm. A series of tablets to the Strangways family at Melbury Sampford may also be mentioned. The large Mildmay wall-monument, 1784, in Sherborne Abbey is by T. Carter.

The fine figure of Robert Goodden at Over Compton, executed in 1825, is by far the most important of the 19th-century memorials in the area. Another whole-length figure sculpture is at Melbury Sampford and is by Chantrey, 1821. Amongst the monuments of neo-classical design examples at Over Compton, Frampton and Fleet are worthy of remark, and at Sydling St. Nicholas are some small wall-tablets by Lancashire and Son of Bath which are unusual.

A hatchment, of the unusually early date of 1658, survives at Folke and there are two others of 1693 (?) and 1703–4 at Forde Abbey and one at Sherborne Abbey of 1708–9. Painted achievements on wood panels, of a similar character, are used as memorials at Poyntington and elsewhere.

Paintings: Mediaeval ecclesiastical wall-paintings are very uncommon in the district and only the examples at Cerne Abbas are of importance. These date from the 14th century and represent scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist. There have been paintings of some importance over the chancel-arch at Puncknowle but these are not now identifiable. The paintings at Netherbury, discovered about 1850, have again been covered and the painting of the Mass of St. Gregory, formerly at Abbotsbury, has also disappeared. Remains of early painted decoration on the N.W. doorway at Sherborne Abbey are worth mention. There are 17th-century figures of Death and Time in Loders church and texts etc., dated 1679 at Cerne Abbas. Painted roofs are few; fragments at Bradford Abbas and Yetminster are of the 15th century.

Various houses have fragments of painted wall-decoration, as at the Queen's Arms Hotel, Charmouth. Melbury House has an elaborate painted decoration to the main staircase, of which one of the minor panels is signed and dated G. Lanscroon, 1701; the N.E. room has a ceiling of c. 1700 painted with birds, fruit and flowers. Lord Digby's School at Sherborne has an early 18th-century staircase with important paintings by Thornhill of the Calydonian boarhunt etc., and at the Manor House, Beaminster, is a ceiling-panel by Andrea Casali of the Feast of the Gods, brought from Fonthill.

Panelling: The district is not particularly rich in panelling but most of the larger houses retain a certain amount, often reset. Linen-fold panelling is to be seen at Parnham (Beaminster), Melbury House, Melplash (Netherbury) and Sandford Orcas Manor House. At the last house there is also panelling of the end of the 16th and the early part of the 17th century. Trent Manor House and Wynford Eagle Manor Farm both have rooms lined with 17th-century panelling with enriched friezes and there is enriched panelling of importance of the same date at Forde Abbey (Thorncombe); other 17th-century panelling may be mentioned at Sherborne Castle (Castleton), Parnham and Folke Manor House. There is a considerable amount of early 18th-century panelling in the district; the best is perhaps at Melbury where there are also carved festoons ascribed to Grinling Gibbons. Kingston Russell House, Bettiscombe Manor House, Puncknowle Manor House, Lord Digby's School (Sherborne), Forde Abbey and Ilcombe Farm (Netherbury) have panelling of the same period. The 18th-century Gothic fittings of the library at Sherborne Castle have been applied to the 17th-century panelling on the walls.

Piscinae: Very few fittings of this class in the district are of any great importance. There is, however, a 12th-century pillar-piscina at Batcombe, 13th-century piscinae, worth mention, at Little Bredy and Maiden Newton and 14th-century examples at Cerne Abbas and Pilsdon. The best 15th-century piscina is at Burton Bradstock.

Plasterwork: West Dorset contains numerous and important examples of decorative plasterwork of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. There are handsome late 16th-century ribbed and enriched ceilings at Melbury House and Mapperton and a ceiling dated 1601 at Lyme Regis (7). A series of early 17th-century ceilings survive at Sherborne Castle (Castleton) and others of the same period at Burton Bradstock (2), Folke (4) and elsewhere. The enriched barrel-ceiling of the chancel at Abbotsbury church was put up in 1638 and has numerous shields of Strangways heraldry. Forde Abbey has a remarkably fine series of plaster ceilings of the second half of the 17th century and there are early 18th-century ceilings at Melbury House and Kingston Russell. Later 18th-century plasterwork is at Mapperton Manor House, c. 1760, Wootton House in Wootton Fitzpaine, c. 1765, and in the dome at Sadborow, Thorncombe, 1773–5.

Plate: The churches of W. Dorset possess no examples of pre-Reformation plate, the series beginning with the Elizabethan period. Of this age there survive thirty-six cups and numerous cover-patens; six of the cups date from 1570, six from 1571, one from 1572, five from 1573, four from 1574, two from 1575, one from 1576 and one from 1578. Most of these are of the normal form but the example at Shipton Gorge is of unusual wine-glass shape. The cups, such as those at Lyme Regis and South Perrott, of the immediately succeeding period, are still of Elizabethan character but there is an unusual cup with laminated decoration at Wraxall. Other 17th-century plate of note includes a cup at Melbury Sampford of 1607 with a crucifix, cups and cover-patens at Mapperton and Hillfield and cups at Sherborne Abbey. Mosterton possesses an enriched cup and cover-paten given in 1714. There is a certain amount of secular plate now belonging to the Church and of this the fine cup of 1683 at Melbury Sampford, the repoussé beaker of 1676 at Maiden Newton, the bowl of 1710 at Mapperton and the taster of c. 1700 at Litton Cheney may be mentioned in addition to the cups with baluster-stems at Beaminster, 1611, Poyntington, 1634, and Whitchurch Canonicorum, 1662, and a later cup, of 1797, also at Beaminster. A flagon of 1722 at Thorncombe and a plainer one of 1664 at Poyntington are worthy of note. Of the later 18th-century plate the set of 1733 at Bradford Abbas, formerly at Clifton Maybank, the set of 1737 at Trent and the examples of the work of Paul Lamerie (1747–8) at Abbotsbury, Melbury Sampford and Melbury Osmond may be mentioned. These last three churches have breadknives given by Mrs. Strangways Horner, c. 1755.

Pulpits: At Frampton there is a much restored stone pulpit, with carved figures in the panels, dating from the 15th century. The earliest oak pulpits are those at Broadwindsor, Hillfield and Thorncombe; all are of the first half of the 16th century and the two last have linen-fold panels; the pulpit at Broadwindsor has buttressed angles and panels with conventional foliage. There are a number of handsome early 17th-century pulpits of which five still retain their sounding-boards in position; the finest are the elaborately enriched pulpit at Abbotsbury and the example at Lyme Regis dated 1613; the pulpits at Cerne Abbas, Holnest and Leweston possess sounding-boards and at the last-named place the clerk's desk has been retained. The pulpit at Bradford Abbas is dated 1632; its sounding-board now forms a table. Of the same period there is a very handsome pulpit at Netherbury and others of note at Beaminster, Whitchurch Canonicorum and Oborne. Of early 18th-century work the pulpit at Forde Abbey may be mentioned. The sounding-board and standard of the mid 18th-century pulpit in the Congregational chapel at Lyme Regis survive though separated, and the pulpit in the Unitarian chapel at Bridport is an example of good cabinet work of the end of the century. The pulpit at Trent has carved figure-subjects and is of foreign, probably Dutch, origin.

Reredoses: The most remarkable reredos in the district is the late 15th-century painted triptych, probably of the Cologne school, in the hospital at Sherborne. In the abbey are preserved sculptures and decorative fragments of stonework which no doubt formed part of former reredoses, destroyed at the Reformation. There is a 17th-century reredos at Leweston, forming part of the panelling of the chancel. The wooden reredos at Castleton church dates from c. 1714 and there is a handsome reredos at Abbotsbury erected in 1751.

Royal Arms: There is a stone-carving of the Stuart Royal Arms in the Town Hall at Lyme Regis. Post-Restoration painted Royal Arms occur at Long Burton, 1682, Castleton church, (Sherborne), 1671, Puncknowle, 1673, etc. A Prince of Wales feathers with the initials of Prince Henry and the date 1611 is preserved at Sherborne Abbey.

Screens: There are five examples in W. Dorset of churches with stone screens between the chancel and nave; they are all of the 15th century and have been more or less restored; these churches are Batcombe, Bradford Abbas, Cerne Abbas, Nether Compton and Thornford. There are remains of a stone screen also under the W. arch of St. Mary le Bow Chapel in Sherborne Abbey. The finest timber screen is the 15th-century structure, retaining its vaulted loft, at Trent; the screen under the tower at Sandford Orcas may also be mentioned. There is a good early 17th-century screen at Folke and screens of the 17th century at Long Burton and in the chapel at Forde Abbey. In the larger houses of the district there are a number of hallscreens of which that at Melplash (Netherbury) dates from the 16th century. Others, of the following century, may be noted at Parnham (Beaminster), Mapperton and Sandford Orcas Manor House.

Staircases: The most unusual staircase in the district is the early 16th-century tower-staircase in Stratton church; it is a circular timber structure with a central post and linen-fold panelling. The only other church-staircase which need be mentioned is the 17th-century example reset at Castleton (Sherborne). Melbury House has an early 16th-century stone staircase in the tower-building, with barrel-vaults of four-centred form. Sandford Orcas Manor House has two spiral staircases, and an early 17th-century stone staircase at Sherborne Castle has some balusters of the same material. Folke Manor House and West Hall in the same parish have early 17th-century staircases of interest, both have continuous newel-posts. The staircase at Parnham (Beaminster) has pierced terminals to the newels, and the staircase of the same period at Clifton Maybank may also be mentioned. Perhaps the finest staircase in the district is the richly ornamented example of the middle of the 17th century at Forde Abbey; the same house has also a secondary staircase of interest. Two staircases of the turn of the century set back to back are at Melbury House; one of these has a painting on the soffit dated 1701 and an unusually early example of the bracketed string. Other early 18th-century staircases may be mentioned at Kingston Russell House, Lord Digby's School (Sherborne) and Bettiscombe Manor House. At Mapperton Manor House the staircase introduced into the N. wing in the third quarter of the 18th century is contained within the S. half of the stair-hall and, seen from the N., the ascending tiers of balusters in considerable numbers make a striking display. The stone semicircular staircase at Sadborow (Thorncombe), 1775, has wrought-iron balusters.

Stalls and Seating: The only surviving stalls with misericordes in the district are at Sherborne Abbey. Here there are five on each side, partly made up with modern work, but mainly of the 15th century; the carvings include a Last Judgment. The best pews are those at Bradford Abbas and Trent; both have elaborately carved bench-ends with figures, foliage, etc., and date from early in the 16th century. There is good early 17th-century seating at Leweston.

Weather-vanes: An unusual example of a weathercock with the date and maker's name upon it is on the spire at Trent.

The Early Church at Sherborne

The position and form of the later pre-Conquest Cathedral of Sherborne, though a matter of considerable interest and importance, could not suitably be dealt with in the body of the Inventory which should obviously confine itself to visual facts. It has been thought desirable however to deal with the matter more fully in this section, where theory and perhaps even surmise may be indulged in with greater propriety.

The only pre-Conquest cathedral of this age, the actual form and structure of which is known, is that at North Elmham, Norfolk, and this building, situated in a distant province and erected under different local conditions need have no bearing on the form of such churches in Wessex. It will be a safer guide to bear in mind the extensive structural remains at Deerhurst, Breamore and elsewhere, which may more nearly represent a Wessex cathedral, though on a smaller scale. At Sherborne the Benedictine rule was introduced by Bishop Wulfsige in 998 and it may be that the cathedral was rebuilt at or before that time as the surviving doorway would appear to be of the second half of the 10th century. This doorway, at the W. end of the N. aisle of the nave, with the surrounding rubble walling is now the only certain surviving portion of the pre-Conquest church. The rubble walling however at the W. end of the S. aisle is of precisely similar character and is perhaps also of the same date. This equation is strengthened by the projection from this same wall of the top stones of a moulded stone plinth belonging to a wall which projected some 21 ft. westwards. This plinth was uncovered about 1875 by R. H. Carpenter, architect to the church, who surmised with much acumen that it belonged to a pre-Conquest porch or tower; he further discovered a massive foundation some 20 ft. W. of the W. front, which he thought might well have formed the west side of such a tower. The plinth-moulding, though weathered, is still in part recoverable and is assignable with some degree of probability to the 10th century as it departs widely from the standard mouldings used by the Anglo-Norman builders. The accuracy of Mr. Carpenter's observations have now been firmly established by the excavation undertaken by the Commission in April 1949. This excavation revealed the massive S.W. angle of the tower and a portion of the outer edge of the foundation of the W. wall near the axial line. It is remarkable that both the S. and W. walls seem to have had no inner face and the tower must thus have stood on a solid platform. A portion of an added wall was also uncovered projecting to the south of the S. wall, with a straight joint between the two. The mortar in both cases was whitish and showed no marked difference the one from the other. The date of the destruction of this tower can be arrived at within certain limits. The parish church of All Hallows was erected late in the 14th century immediately to the west of the existing nave and its erection would have compelled the destruction of the earlier tower if indeed it still existed at that date. Thatit did so exist is perhaps supported by the curious recessed frontage of the existing nave which seems almost certainly to represent the internal wall-face of the destroyed tower, the thickness of the earlier wall being represented by the existing wall and the bench against its internal face. Mr. Carpenter records that when the great W. window was extended down to its present sill-level, thus adding the two lowest tiers of lights, the operation involved the destruction of certain arches cut through the wall. The height of these arches above the floor-level might perhaps indicate that they resembled the twin arches with triangular heads still surviving in the E. wall of the tower at Deerhurst at about the same height.

The position of the surviving pre-Conquest doorway at the end of the N. aisle argues, very strongly, that the church of that age had aisles, into one of which the door opened, as it is difficult to suggest what other purpose might have been served by such a doorway in the W. front.

There remains only to be considered what evidence, if any, exists for the form of the pre-Conquest church to the E. of the nave. It can be shown from existing remains and documentary evidence that most of the major churches of late 10th and early 11th-century date were cruciform on plan and had a well-defined crossing supporting either a masonry tower or a timber lantern. The distinguishing feature of those crossings is that they were wider than the chancel and transepts, and perhaps than the nave also, thus forming salient angles between those parts of the structure. This feature appears, markedly, in the crossings at Stow, Lincs. (early 11th century), at St. Mary, Dover, Breamore and elsewhere; it is largely confined to churches of this period, indeed so much so, that its presence is presumptive evidence of this date.

It is a curious fact that in two surviving major Dorset churches, Sherborne and Wimborne, this same feature is observable, though in fact both crossings are translated into what is now avowedly 12th-century work. Both churches were Anglo-Saxon minsters of some importance and it seems not improbable that in each case the older lay-out of the crossing was preserved when the crossings were rebuilt or perhaps only refaced in the 12th century; this appears the more probable in that salient angles to the crossing were an unknown feature elsewhere in AngloNorman building.

If this be granted as a hypothesis, the unusually short naves of both churches receives a fresh significance, that at Sherborne being only five bays long while the 12th-century nave at Wimborne was shorter still and only of four bays. This might well represent the restricted dimensions of the pre-Conquest nave in both cases and is quite at variance with the normally prolonged naves of the Anglo-Norman builders.

This brings us to the extremely difficult problem of why the baying of the existing nave at Sherborne is so pronouncedly irregular. This irregularity is in no way assignable to the 15th-century builders, who recased or rebuilt the two arcades, as it bears no relationship to the setting out of the clearstorey or of the stone vault, which are both avowedly of this period alone. It must therefore have been conditioned by the pre-existing structure whether this structure were of 12th-century or earlier date. Now there survive at the E. end of both arcades parts of the semi-cylindrical 12th-century responds and higher up both walls are the impost mouldings representing the height of the capitals of the responds and also, on the N. wall, the enriched string-course at the base of the triforium. Setting this out on paper it would appear that the width of the 12th-century bay, as proposed if not actually executed, could not have been more than about 14 ft. allowing for the semi-circular arch below the triforium string-course. Furthermore the lines of both responds, towards the nave, show that any resulting 12th-century arcade could not have been included in the existing piers as they would have extended beyond their limits.

Setting this dimension out on the plan it becomes clear that the regularly spaced bays of a 12th-century nave could not have been responsible for the erratic lay-out of the existing arcades and the six bays of the nave are not extensive enough to allow of two if not three successive campaigns of building to explain this irregularity, particularly as so great a builder as Bishop Roger of Salisbury was directly concerned in the matter.

Sherborne Abbey Anglo-Saxon and Norman Lay-Out

One explanation alone would seem to fit the facts, and that is that work on the church had only reached the crossing and the E. responds of the nave when Bishop Roger fell from power in 1139 and that the rest of the pre-Conquest nave was then still standing. Pre-Conquest building, as is well-known, was not distinguished by any degree of exactitude in the settingout of the structure or of precision in the symmetry of the piers, and furthermore, the structural history of the early nave is entirely unknown. It is thus perhaps remotely possible that the irregularity of the existing nave is due to unknown factors of this nature the character of which it is idle to surmise.

One other feature of the existing central crossing remains to be touched upon; this is the remarkable quadrant projections set within the southern and northern angles, respectively, of the N. and S. transepts. It may perhaps be assumed that similar projections formerly existed in the corresponding angles of the presbytery and nave and that these have not survived owing to the absence of responds to the E. and W. tower-arches, to allow the choir-stalls of the 12th-century choir to be set flat against the side walls. If we may thus assume that the four piers of the pre-Conquest crossing were symmetrical it becomes necessary to suggest some motive for the quadrant projections, which certainly serve no obvious purpose in the 12th-century building; indeed they are not carried up above the vault or ceiling of either transept and are completely absent at the 12th-century lantern-level of the central tower. A glance at the plan of the pre-Conquest crossings at Stow and elsewhere shows that the tower-arches are butted against the salient angles of the crossing which represent a continuation of the outer face of these arches in each case. We should thus assume that at Sherborne the quadrant projections represent, in their lower portions, the responds of the earlier tower-arches, forming when complete, more than a semi-circle on plan and equating exactly with those of the surviving E. arch of the former central tower at Deerhurst. If this be accepted, it carries with it the corollary that, when the 12th-century builders came to recast the crossing, they set their own arches within the lines of the pre-Conquest ones, thus reducing the width of the tower on all four sides and setting their own responds within the lines of the pre-Conquest crossing. A precisely similar step and for a precisely similar purpose was taken, in the 14th century, in the crossing at Stow. By this action the 12th-century builders left only part of the semi-cylindrical respond-shafts exposed and these they certainly refaced, thereby increasing their girth. They were further carried up the full height of the transepts to finish ineffectively at the ceiling-level. This explanation may, perhaps, seem somewhat laboured, but so unusual a feature may well demand an unusual explanation and it may at least be worth while putting it on paper for lack of a better.

To conclude, there exist impressions of an unusually early common-seal of the abbey which is by general consent ascribed to the 11th century; four Cs, all of the early square form, are used in the legend. The seal thus antedates the Anglo-Norman church, which in part survives, by a generation or more. On the face of the seal is represented the side view of a church (see fig. below) which differs markedly from the conventional representations so common on mediaeval seals. So much is this the case that, though inevitably contracted in length, the church would appear to be an honest attempt to represent the then existing building, with its apse, turreted crossing, nave, west tower and a porch beyond it.

All the particulars dealt with above are illustrated on the accompanying plan of the 12th-century and earlier building.