Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Introduction', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp3-27 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Introduction', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp3-27.

"Introduction". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp3-27.

In this section

Introduction

London's topographical entities have a tendency to shift over time. As mostly imagined today, Clerkenwell has been adjusted down in size to a compact 'urban village' just north of the City. Its heartland is Clerkenwell Green, with St James's Church raised above it and the serpentine Clerkenwell Close wrapping quaintly round the church and away to the north, where the district peters out around the line of Rosebery Avenue.

That understanding coincides with the core of the recent 'renaissance' that has raised Clerkenwell from a mid–twentieth century nadir of morale to a synonym for urban rejuvenation and energy. It also tallies with the nucleus of local power, activity and population for some six hundred years after the parish was founded. But it omits most of the land-area belonging to the historic parish from its twelfth-century beginnings down to 1900. That stretched much further north, up to and beyond Pentonville Road to include the planned suburb of that name. At its northeastern extremity its boundaries took in the Angel and the west side of Islington High Street, while to its north-west it stopped little short of King's Cross.

These northern areas of Clerkenwell were first systematically built up as residential suburbs between about 1770 and 1840, in line with the patterns of London's growth on freehold estates during that era. They have many linkages with the longer-developed areas to the south, and some parts have been rebuilt almost as often. Nevertheless the two portions of the parish retain fairly separate identities. The present pair of volumes of the Survey of London therefore breaks approximately along the lines between these sibling districts (Ill. 1). Volume XLVI covers south and eastern Clerkenwell; volume XLVII deals with northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. The two books are separately introduced. This introduction addresses the topography, architecture and broader history of the whole area, together with the special character of the southern district, while its counterpart in volume xlvii takes as its main theme estate development and the housing of northern Clerkenwell, private and public.

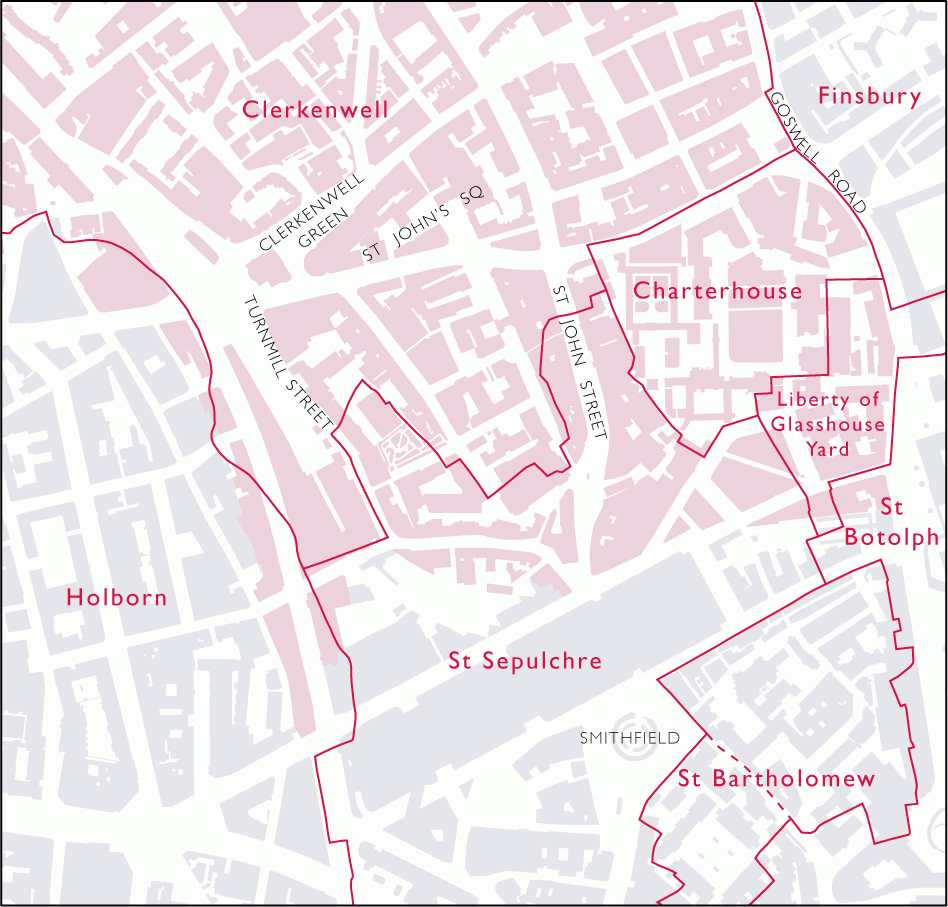

A note must be inserted at this juncture about the precise area covered by the present volume and its relation with later administrative districts. The Survey of London normally proceeds by parishes and follows their boundaries, with small exceptions for reasons of convenience. These volumes conform to that pattern. Over and above Clerkenwell, volume XLVI also includes slivers of the parish of St Andrew, Holborn and, more significantly, a narrow buffer zone separating Clerkenwell parish from the City of London (see Ill. 3). The latter zone, lying north and east of Smithfield and including Charterhouse Square, the southern end of St John Street, Cowcross Street and most of Turnmill Street, never belonged to Clerkenwell, though it is widely taken to be part of it today. In the post-medieval period it was split between separate jurisdictions, explained in more detail on pages 6–7. It was united administratively with Clerkenwell only in 1900, when both became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury, which took in also the old parish of St Luke's further east. Finsbury in its turn ceased to be a unit of government when the present London boroughs were created in 1965. At that date Clerkenwell, along with Finsbury's other constituent elements, became part of an enlarged London Borough of Islington. With minor exceptions, the area described in the two volumes falls today for administrative purposes entirely within Islington. A small detached portion of the former parish of Clerkenwell in Muswell Hill is naturally excluded.

Apart from one major complex of buildings, the whole zone between the City and the old parish of Clerkenwell is included in this book. The omission is the Charterhouse, the subject of a Survey of London monograph to be published following the present volumes.

Some 350 acres in extent, Clerkenwell rises consistently from around 50 feet above sea level at its southern end up to the heights of Pentonville and the Angel, at around 125 feet. Its one original natural boundary was the Fleet River on its western edge. Long lost to view beneath or west of King's Cross Road and Farringdon Road, and often diverted from its former course, the Fleet exerts a latent influence upon the local topography. It manifests itself, for instance, in the sharp descent down Lloyd Baker Street and Wharton Street to King's Cross Road, in the similar slope of Mount Pleasant, and in the urban chasm around the intersection of Clerkenwell Road with Farringdon Road, created when the latter thoroughfare combined with the Metropolitan Railway to purge, widen and deepen the Fleet valley in one of the seminal clearances of Victorian London.

Much of Clerkenwell's geology, its lower-lying portions close to the City especially, consists of layers of gravel upon impermeable clay. These, together with the permeable 'loess', so valuable for brick-earth, were conducive to the springs and wells recollected in the parish's name and bound up with its early repute. Writing in 1598, John Stow lists a series of wells close to the eponymous 'Clarkes well', including Skinners Well, 'Fagges Well, neare unto Smithfield by the Charterhouse, now lately dammed up, Todwell [probably Godwell], Loders wel, and Radwell, all decayed, and so filled up, that there places are hardly now discerned'. (fn. 1) Not all of these can be identified. But from Faggeswell in the vicinity of Charterhouse Lane the Faggeswell Brook ran west to join the Fleet, its course perhaps once defining the City's ragged northern boundary. Goswell Road also most likely took its name from a watersource lost to posterity, possibly Stow's misspelt Godwell or Godewell, easily corrupted to 'Godswell'.

The location, control and exploitation of water supply are recurrent themes in Clerkenwell's history. In due course piped water replaced wells and streams as the main means of provision. The trend began early on with the religious houses; then in 1613 came the advent of the New River, whose associated pipes, reservoirs and landholdings coloured the whole destiny of northern Clerkenwell. Even after that wells could be discovered and promoted, partly for their medicinal value, increasingly as venues for organized amusements and pleasures. The most famous is Sadler's Wells, a precariously enduring place of entertainment for Londoners from its inauguration in the 1680s to the present day. Among others long gone were the Cold Bath of Coldbath Square, connected with a spring exploited from 1697; New Tunbridge Wells, sometimes known as Islington Spa, close to Sadler's Wells; the London Spaw; and, just beyond the area covered by these volumes, Bagnigge Wells. Till well into the nineteenth century the area north and south of Pentonville Road had several pleasure grounds, of which White Conduit House just beyond the parish boundary was the most famous. Later, good spring and well water were crucial also to the success of large breweries and distilleries such as Gordons, Booths and Nicholsons. Only in recent years has local extraction fallen off and Clerkenwell's water table risen, as elsewhere in formerly industrial London. At the time of writing, water trickles again in the Clerks' Well after many dry decades.

By virtue of its name, this well—visible today by appointment under Nos 14–16 Farringdon Lane, half-lost to memory more than once and rediscovered in 1924—is the most venerable of Clerkenwell's water sources. It can be confidently identified with the 'fons clericorum', one of three wells mentioned in William Fitzstephen's famous description of London (c. 1183) as places of popular resort 'visited by thicker throngs and greater multitudes of students from the schools and of the young men of the City, who go out on summer evenings to take the air'. (fn. 2) With Elizabethan nostalgia, Stow recounts that the Clerks' Well took its name from 'the parish clerks in London, who of old time were accustomed there yearly to assemble, and to play some large history of Holy Scripture'; and he goes on to cite festivals of three and eight days held at nearby Skinners' Well during the reigns of Richard II and Henry IV. (fn. 3) Parish 'clerks' as such did not exist before the Reformation, and he was probably extrapolating from Fitzstephen's use of the word 'clerici', meaning clergy. Stow's words still have imaginative resonance, however. Peter Ackroyd, for instance, has written of the Clerks' Well as 'the site of the stage where mystery plays were performed for centuries "beyond the memory of man"'. (fn. 4)

We should be wary of too exalted a reading of such events. There is a possibility that the phrase 'fons clericorum' predates the foundation of the religious houses close by, as the following paragraph explains. On the other hand hard evidence for the sacred side of observances at the Clerks' Well seems to boil down to a single French phrase, 'miracles et lutes', in a complaint from the prioress of St Mary that crowds of Londoners trampled down her nunnery's hedges, fields and crops when they congregated at these frequent gatherings. Edward I's sympathetic response, dated April 1301, called for the better control of 'luctas et alios ludos'—wrestling and other games of a kind popular on the fringes of medieval London. (fn. 5) For these the local record is sharper and fuller. There are fifteenth-century references to 'le wrestlyngplace' north of the Charterhouse site, while Stow laments that wrestling had usurped the sacred plays at Skinners' Well. All in all, Sadler's Wells and Clerkenwell's other later entertainment venues around water-sources appear faithful enough descendants of the Clerks' Well.

Clerkenwell's relatively few traces of Roman occupation can be interpreted as agricultural. Though there are some archaeological signs of settlement from the sixth century, it is not singled out in Domesday Book. The decisive date in its chronology is 1144–5, when two of the three monastic foundations fundamental to the parish's history and landholdings then make a near-simultaneous appearance. These were the Hospitallers' priory of St John of Jerusalem and the convent of St Mary, sited within a stone's throw of one another: the priory, in modern terms, around St John's Square, and the nunnery around St James's Church in Clerkenwell Close. Both were founded by Jordan de Bricet(t), from a family perhaps of Breton origin that also held extensive lands in Essex. They were endowed from de Bricet's fee of Clerkenwell which he held of the bishop of London within the manor of Stepney by knight service. (fn. 6) It is in early charters of the two foundations that the Latin form of the place-name ('iuxta fontem clericorum') is first recorded. From a reading of a grant of tithes in one of these texts, it is possible to push back the name to 1112, before the foundations existed, but this interpretation is by no means certain.

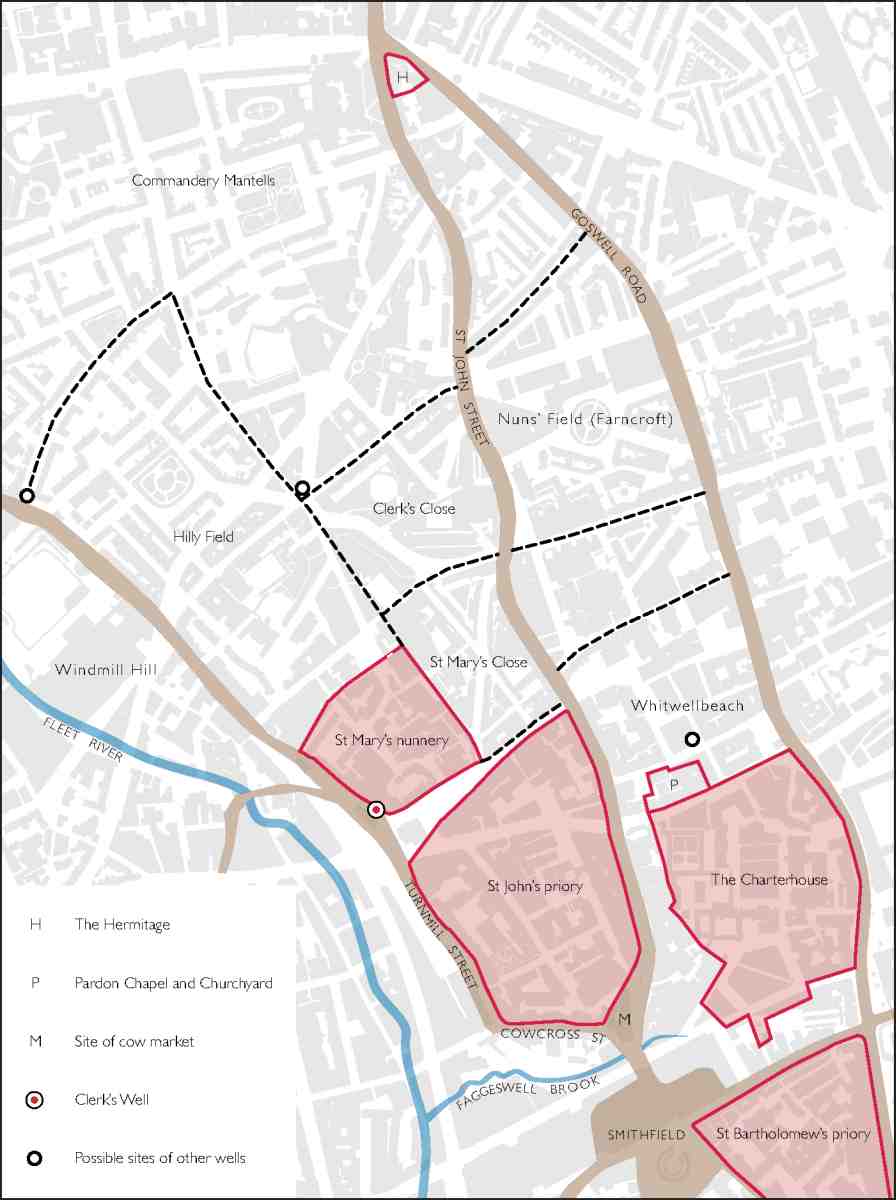

2. Medieval Clerkenwell and Smithfield, showing monastic houses, main roads and other features, superimposed on the modern street plan. Names of roads shown are modern

The details of the grants and extent of the lands attached to the two religious houses are opaque, but it is agreed that the priory slightly preceded the nunnery. Once a dispute had been settled between them, the nunnery's own property seems to have been confirmed as ten acres apparently including the Clerks' Well; an extra four acres between this land and the priory, identifiable with the present Clerkenwell Green, came afterwards and more loosely under the nuns' control. The priory likewise enjoyed some ten acres adjacent to its buildings (Ill. 2). In addition, through de Bricet's descendants both foundations came to control much larger tracts of land further north in the parish. A daughter and granddaughter of Jordan de Bricet both became nuns at St Mary's, while through another daughter much of the northern property passed to the Foliot family and hence to St John's.

3. Nineteenth-century parochial boundaries in southern Clerkenwell, Holborn and the City, superimposed on the modern street plan. The area covered by the Survey volumes is coloured pink

Twelfth-century Clerkenwell thus acquired two religious houses as its first recorded landholders and builders. In a pattern typical for the outskirts of European cities, land-use in the parish came subsequently to be shared between such sizeable institutions needing space and isolation (in the first place monastic, later penitentiary), certain kinds of farming and manufacture, tracts for exercise and recreation, and the forces of urbanization, most pressing along the routes in and out of London.

Dominant at first, even after their suppression the religious houses left their stamp upon Clerkenwell. Over nearly four centuries of existence, St John's and St Mary's built substantially and created walled precincts around their holdings. St John's also had an outer precinct, gated if not entirely walled. Ground in their immediate environs was always let out to tenants wishing to avail themselves of the orders' religious and economic authority, while well before the Reformation powerful households were choosing to live within the precincts. As for their buildings, the more impressive remains have been left by St John's priory, the richer of the de Bricet foundations. Of the original Hospitaller church of c. 1144–60, with its round nave (typical of the military orders) joined to an apsidal chancel over a crypt, three bays of the crypt survive. To its south St John's Gate (1504), Prior Docwra's entry to the inner precinct, is Clerkenwell's most conspicuous monastic monument, battered and restored but still most dignified. St Mary's has left almost no traces above ground. But from the nunnery church's enlargement for local parochial needs in the 1180s and 90s stem the origins of the present St James's parish church.

It is the third and last of the district's monastic foundations which has left the most abiding mark. Founded in 1371 by Sir Walter Manny, the London Charterhouse was an interloper in the local land-pattern. Bound up with the reaction to the trauma of the Black Death, it grew out of a chapel with a plague burial ground erected in 1349. The Charterhouse took land in the zone between Clerkenwell and the City, belonging partly to St John's priory and partly to St Bartholomew's hospital. In its lifespan of less than two centuries, this latecomer acquired an august presence and a modest landholding to its north, represented by what later became the Charterhouse estate. The vagaries of its post-Reformation fate, when the core of the Charterhouse became successively a private house and then in 1611 an almshouse—cum—school, allowed one fifteenth-century court, Wash-house Court, and other vestiges to survive. The relationship between the Charterhouse and its gated precincts and grounds also endured. Today's visitor to Charterhouse Square, the monastery's former outer precinct or yard, instantly senses the seclusion of a cathedral close or Oxbridge college. Such is the significance of the Charterhouse that its buildings have been reserved for a separate monograph, but the square and its environs are described in Chapter IX of this volume.

The administrative history of the area between these three foundations and the City—the 'buffer zone' south and west of Clerkenwell parish (Ill. 3)—is involved. Most of it once belonged to the parish of St Sepulchre. That church, on the north-western edge of the City, existed by 1137 and probably some time before. It is tempting to suggest some connection between St Sepulchre's and St John's priory, since the Knights Hospitallers were devoted to the Holy Sepulchre. Bounded on its west by the Fleet, St Sepulchre's parish extended northwards to take in Cowcross Street and part of Turnmill Street (in modern terms). Further east, the parish may have been curtailed when the Charterhouse was founded, though some of the land then taken belonged to St Bartholomew's hospital.

After the Charterhouse's abolition, its former precinct remained extra-parochial at first. But at an unknown date no later than the 1670s, the outer precinct's western portion was allotted to St Sepulchre Without, as the section of that parish outside the City came to be called, while its smaller eastern portion, up to the line of Aldersgate Street and Goswell Road, became part of the parish of St Botolph without Aldersgate, the division between them running north—south through Charterhouse Yard. Around 1700 this eastern portion became part of a curious administrative entity known as the Liberty of Glasshouse Yard, which survived precariously until the London local government reform of 1900.

***

The clustering of tenements round the three religious houses cannot be separated from the spread of late medieval London, especially around the Charterhouse, whose outer precinct touched to the south upon the City boundary. The first continuous urban development in the area covered by these volumes naturally took place nearest to the City, and along the three main roads northwards of the entry points into London at Smithfield and Aldersgate bars. These roads—St John Street, Aldersgate Street—Goswell Road, and Cowcross Street—Turnmill Street—acted with the monasteries as linked magnetic fields, drawing development along and around them (Ill. 2). Their chronology and mutual relation are obscure.

St John Street, perhaps the first of these historic north-south routes, provided a direct way to and from Islington, the next sizeable settlement north of Clerkenwell. It ran along the east side of St John's priory, just as Cowcross and Turnmill Streets flanked its southern and western edges. In existence by 1170, it either predated the priory or was laid out by the Knights Hospitallers, who certainly exploited it. But it was always a public road. A fourteenth-century decree ordered customs to be paid on goods entering London via St John Street in order to pay for the road's upkeep. At that date it was probably the prime route for traders and for drovers bringing animals to Smithfield, where a general livestock market flourished by the twelfth century, and to the semi-separate cattle market next to it at Cow Cross, the open space where St John Street and Cowcross Street meet. The tenements of St John Street, as they developed, furnished lodging for visitors and income for the Hospitallers. Over time the street acquired quite a cluster of the courtyard inns typical of the highways in and out of London, and evolved into a major rendezvous for the Georgian coaching trade.

The early history of Aldersgate Street and Goswell Road, also leading to Islington, is less clear. Its oldest portion, which went by various names, is supposed to have proceeded northwards from Aldersgate bars only up to the present line of Clerkenwell Road and Old Street, north of which point the road may once have turned eastwards. The direct northward continuation of Goswell Road is attested only from the fifteenth century. Aldersgate Street in due course attracted some post-Reformation inns of the same kind as St John Street. A larger second group of such inns made its appearance at the northern tip of our area, at the southern end of Islington where St John Street and Goswell Road converged. The most famous was the Angel, which though part of the nucleus of Islington lay within Clerkenwell parish.

The third of the ancient roads northwards was the line now represented by Cowcross Street, Turnmill Street and Farringdon Lane past the Clerks' Well, hence across the Fleet and on towards Barnet. This route, probably also used by drovers and other travellers coming into London from the north-west, continued to be a thorough-fare until the 1750s, when the New Road (Marylebone—Euston—Pentonville Roads) encouraged them to proceed eastwards as far as the Angel and then turn south along St John Street or Goswell Road. Along Cowcross and Turnmill Streets, skirting the outer precinct of St John's priory, there were already in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries narrow plots for housing and manufactures. Powered from the Fleet and partly owned by the priory and nunnery, the mills of Turnmill Street were the area's original industrial concentration. The 'revolving mill-wheels' in the pasture lands north of the City whose 'merry din' so delighted William Fitzstephen in his boosterish laudatio of twelfth-century London may well have been here, for this section of the Fleet was called Turnmill Brook from an early date. (fn. 8) They were soon being used not only for corn but for tile-making and by Tudor times for fulling, lead-milling and pigment-grinding, thus polluting the water. As late as the eighteenth century, a house off Turnmill Street was being advertised as having 'a good stream and current that will turn a mill to grind hair-powder or liqourish [sic] or other things'. (fn. 8)

The copious alehouses of Cowcross Street and Charterhouse Lane, close to Smithfield, were small and transient compared to the St John Street and Aldersgate Street inns. In and behind all these streets an ever denser tissue of timber houses and back courts was accruing by the Reformation, slowly transmuting into the urban warren already hinted at by the so-called Agas map, representing London in about 1550. Some such courts resulted from breaking up old houses and gardens with clusters of timber tenements. But even in the period of brick-building right down to late Georgian times, courts and alleys continued to be tucked tightly in behind new streets to meet the need for cheaper dwellings.

From the Elizabethan period there are reports of suburban raffishness, vice and criminality in the network of streets and alleys around Charterhouse Lane, Cowcross Street and Turnmill (sometimes called Turnbull) Street— a problematic district for three centuries to come. By contrast, royal officials and courtiers had raised a few larger secular houses of masonry around the religious precincts by the middle of Henry VIII's reign. One such in St John's Lane was clad in the Renaissance terracotta ornament then in vogue; another, on the east side of Charterhouse Yard, can be linked to Sir John Neville, Lord Latimer, second husband of Katherine Parr. Already in high fashion before the Dissolution, the monasteries' environs were to remain so for another century and a half. In the turbulent years 1538–40, all three religious houses were suppressed and expropriated, the Charterhouse savagely so. But apart from the drastic blowing-up of the St John's nave and tower by Lord Protector Somerset in 1549, the ensuing physical changes in and around them were gradual at first. As their buildings offered a quality of permanent fabric to which few secular families could have aspired, most were taken over, adapted and subdivided. Nor were the fallow portions of the precincts developed straight away. On the south side of Clerkenwell Green, the old St John's property called Butt's Close had been broken up into gardens by the 1570s, though a few houses appeared there soon afterwards. Around the same time the sense of Clerkenwell Green as a public open space firms up, though it continues to be encroached upon for years.

Some of the dynasties that play a lasting role as Clerkenwell freeholders now emerge. On the former nunnery lands, what was to become the Seckford estate was settled after 1587, while in 1599 Sir John Spencer acquired what through his daughter's marriage was to become the larger Northampton estate. But the overall pattern of landholdings, settling down sixty or seventy years after the Dissolution, suggests that the new owners were mostly not resident families with local ambitions but non-residents of one kind or another, private, corporate or institutional. Many were to remain in possession for the next three centuries and more. An example is the freehold between the northern stretches of St John Street and Goswell Road acquired in 1608 by Dame Alice Owen, a judge's widow. After building almshouses and the school that still bears her name (now removed to Potters Bar), she entrusted the property by her will to the administration of the Brewers' Company. Parts of this land are still in the company's charge.

The first local signs of a distinctive Protestant polity appear around 1611–15, about the time when Alice Owen built her school. In those years the Charterhouse was converted into Sutton's Hospital, also part almshouse and part school. And, at a period when there was clamour for firmer control over London's spreading suburbs, Clerkenwell gained two interlinked institutions of county government. Hicks' Hall in St John Street was a purposebuilt sessions house for the Middlesex magistrates, paid for by one of their number, Sir Baptist Hicks. Along with it went the 'New Prison' or Clerkenwell Bridewell, erected north of the parish church because room was lacking next to Hicks' Hall. A workhouse was added in the 1660s for a union of Middlesex parishes. That did not last; instead, a second prison joined the first. In 1792 the original prison, by then termed the Middlesex House of Correction, moved to a site near by in Coldbath Fields where the Mount Pleasant postal sorting office now stands. The second prison, known latterly as the Middlesex House of Detention, carried on until the 1880s and became the site of the notorious Fenian 'outrage' of 1867. As for Hicks' Hall, when it proved too small and dilapidated, it was replaced by the Middlesex Sessions House (1779–82), extant today on Clerkenwell Green.

In its judicial and corrective guises alike, county justice maintained its presence at the heart of Clerkenwell for over three centuries, until the sessions moved away in 1920. While the parish's texture was enriched by these trappings of authority, they did not stop people enjoying themselves. One symptom of tolerance was the continuance of the Red Bull Theatre, created behind an inn of that name in St John Street around 1600. According to J. P. Malcolm, the Red Bull 'was chiefly frequented by the lower order of the people, and said to have been a large building, acted in by daylight, and partly open to the weather'. (fn. 9) Though its rowdy audiences sometimes came before the justices, this little theatre carried on right through the Commonwealth, surviving puritan raids only to close in the laxer 1660s.

With prisons so close, central and southern Clerkenwell was becoming a less eligible address for the nobility. That took time to make itself clear. Around 1630 the 1st Duke of Newcastle could still carve himself a fancy house out of the remains of St Mary's nunnery. Parts of the other old religious enclaves, St John's Court and Charterhouse Yard, also retained their cachet beyond the Civil War. But if the new institutions did not deter the aristocracy, intensification of the urban fabric finally prised them out. Even in protected Charterhouse Yard, the break-up of the Rutland House property in 1660 and the promotion by the 2nd Duke of Buckingham of a short-lived glassworks on its garden hinted at the industrial future. Further north, the 3rd Earl of Northampton built himself a mansion on his extensive Clerkenwell holdings in the 1660s, only for his son to abandon it in the next generation, as housing spread on to the family property's southern fringe.

The arrival of a new style of bourgeois urban living based on the brick house, terraced or otherwise, widespread after the Great Fire, is most graphic in Charterhouse Yard. Between 1688 and 1705 speculators and builders reconstructed three of its four sides, transforming the straggle of the old precinct into a neat square for London's modern merchant classes. On a humbler scale, the narrow streets and small houses of Clerkenwell's first and rather shaky grid, on the Charterhouse estate around Great Sutton Street, belong to the same years. To its north, Compton Street was likewise laid out after 1686 on land belonging to the 4th Earl of Northampton and divided into almost eighty plots, inaugurating the drawn-out story of development on the Northamptons' land. With the exception of just two houses (Nos 4 and 5) in Charterhouse Square, all these dwellings have been obliterated.

After a short pause building resumed with the projection of Britton (then Red Lion) Street in 1718–24, of which rather more fragments survive, and with development from 1719 on the Baynes—Warner estate around Coldbath Fields, now all but illegible. The main promoter of Red Lion Street, Simon Michell, also refashioned the remnants of the old priory church of St John's into a second church for the parish, almost rubbing shoulders with St James's. His aim was to secure the value of his house-building speculations by setting up the equivalent of a proprietary chapel. But he would hardly have been able to sell his interest to the church-building commission had Clerkenwell not been mounting in population, with (according to Edward Hatton) 1,146 houses in 1708. After that the figures, such as we have, rise sharply: 1,500 families or 9,000 people in 1710; 1,529 houses in 1724; and 1,900 houses in 1735. (fn. 10)

***

From about 1720 a pattern for local industry comes into focus. Most early residents of Charterhouse Square and Red Lion Street probably had connections with commerce or manufacture, even if they plied their trades away from their homes. At the cheaper south end of Red Lion Street, however, the first occupants included a clockmaker, John Maberly, whose home was presumably his place of work. Close by in George or St George's Court lived and no doubt worked until 1721 Christopher Pinchbeck, watchmaker, clockmaker and inventor of the copper and zinc alloy that has perpetuated his name.

If not quite Clerkenwell's earliest recorded watch- and clockmakers, these men foreshadow the concentration to come. As with most of the parish's trades, links can be inferred with the City's northern edges, where high-class metal-working in gold and brass had long thrived, along with furniture- and instrument-making. According to the industrial journalist George Dodd, the beginnings of Clerkenwell watchmaking coincided with the introduction of 'the jewelling of watches', a term referring 'not to the outward adornment by means of jewels, but to the use of hard stones as a material in which to make pivot-holes for a watch movement'. (fn. 11) Jewellery and watchmaking were certainly locked together in Clerkenwell. Gathering pace and numbers, the skills spread like wildfire all over the parish. By 1797 almost 7,000 of its population of about 21,000 were estimated to be employed in or dependent upon the watch and clock trades, turning out 70,000 timepieces annually for export and 50,000 for the home trade, with three individual makers, Richard Bayley (Red Lion Street), Smith and Upjohn (Red Lion Street) and Benjamin Webb (St John's Square) claiming to make over 3,000 each per annum. (fn. 12) In 1842 it could be said: 'From St John's Square to the New River Head, and from Goswell Street to Coppice Row, there is scarcely a street which does not contain some artisans in these departments of handicraft, and in many of the streets nearly the whole of the houses are thus occupied'. (fn. 13) From that acme of intensity, the trades fell back after 1870 before lower Swiss wages and American mechanization.

Watchmaking fragmented by nature into different handicrafts and skills, allowing it to be carried on in or behind small houses. Though clockmaking later spawned some purpose-built factories, watchmaking long remained a classic example of the division of labour in manufacturing. Two accounts of the processes at work, though often cited, are graphic enough to bear repeating here. First, The London Tradesman of 1747:

The movement-maker forges his wheels and turns them to the just dimensions, sends them to the cutter and has them cut at a trifling expence. He has nothing to do when he takes them from the cutter but to finish them and turn the corners of the teeth. The pinions made of steel are drawn at the mill so that the watchmaker has only to file down the points and fix them to the proper wheels. The springs are made by a tradesman who does nothing else, and the chains by another … After the watchmaker has got home all the … parts of which it consists, he gives the whole to the finisher, having first had the brass wheel gilded by the gilder, and adjusts it to the proper time. The watchmaker puts his name on the plate and is esteemed the maker, though he has not made in his shop the smallest wheel belonging to it. (fn. 14)

As late as 1903, Charles Booth pictured a similar scene:

The number of subdivisions in the trade is inconceivable. Each worker will be found in a separate house, and at Clerkenwell, where they congregate, almost every front-door in certain streets has its brass-plate stating the owner's special occupation. Here he carries on his profession by himself, working in a room with a north light near the top of a house, or, it may be, in a lean-to shed at the back. (fn. 15)

The contrast between the value of the items handled and the shabbiness of their creators' premises was always striking. In the early nineteenth century Rees's Cyclopaedia remarked:

If we wish to be introduced to the workman who has had the greatest share in the construction of our best clocks, we must often submit to be conducted up some narrow passage of our metropolis, and to mount into some dirty attic, where we find illiterate ingenuity closely employed in earning a mere pittance, compared with the price which is put on the finished machine by the vendor. (fn. 16)

Not all of Clerkenwell's early watch- and clockmaking practice can have been subject to subdivision, much less the instrument-making that flourished in its lee. Some individual masters made many of the parts as well as complete instruments. Nevertheless the outwork system dominated from early days. The self-employment it entailed made the typical Clerkenwell artisan independent, but kept him poor.

Printing, the other major local industry and an even more enduring one, has been more diffuse in scale, siting and chronology. St John's Lane boasted the earliest concentration. Religious publishing was taking place from St John's Gate by the 1670s. From here the Gentleman's Magazine and other titles were issued under the ingenious Edward Cave for half a century from 1731, drawing high-class engravers, print-makers and type-founders around the gate. By the 1750s printing had spread to nearby St John's Square, where a respectable firm, long styled Gilbert & Rivington, had premises on the west side for many years. There it seems for the moment to have paused. Not until the mid nineteenth century did it ramify, as Clerkenwell was sucked deeper into London.

Among other local industries tanning, slaughtering, butchery and bacon-curing held sway in the scruffy courts within reach of Smithfield, as well as east of St John Street. Further up that street, an eighteenth-century sheepskin market could be found on Northampton land. At the level of artisan skills, there was a scatter of furniture–making by the mid-Georgian period. In a final blow to upper-class domesticity, Newcastle House next to the parish church was taken over by cabinet-makers in 1736; other such firms appear in Clerkenwell Green, Britton Street and St John's Square shortly afterwards, some of them no doubt making clock cases. For the moment these industries made no distinct impact on the urban fabric. The only evident signs of enlarged scale before 1800 were some big wholesale warehouses clustering around the bottom end of St John Street by 1720, and a number of breweries and distilleries along the same route, often offshoots of its ample inns. In the Charterhouse garden, smoke from the copious local 'Brewhouses, Distillers and Pipe-makers' was already damaging produce in 1731.

The surge in autonomous, skilled trades promoted an articulate artisan class among the watchmakers and printers, and led to Clerkenwell's growing reputation as a radical meeting-place, private and public. Among the watchmakers, a trigger for unrest was a short-lived tax on their trade in 1797 followed by the long wartime and post-war depression. Yet before the French Wars and their politico-economic aftermath radicalized these classes, there had been a record of educated dissent as well as of spasmodic riots hereabouts. Local factors also played their part: the City's proximity; the challenge of the sessions house and the prisons; space to congregate—confined at Clerkenwell Green, broader at Spa Fields, where the great mass-protests of November and December 1816 took place just before the land was built upon; and the pubs and pleasure venues of outer Clerkenwell, half-licensed outlets for self-expression.

As long as southern and central Clerkenwell marked the urban limit, home and work mostly intermingled. The emergence of a residential north of the parish, apart from an industrial centre and south, took time to establish. It was never absolute. But it began to be glimpsed from the 1770s, with the creation of Pentonville—the first known English suburb to deploy the 'ville' suffix—on Henry Penton's land around the New Road. Pentonville began more as an offshoot of Islington than as a Clerkenwell-based venture. Smaller parallel developments, like Rawstorne Street on the Brewers Company trust land between St John Street and Goswell Road, helped shape fresh areas of inhabitation with, so it was hoped, a domestic and middle-class future.

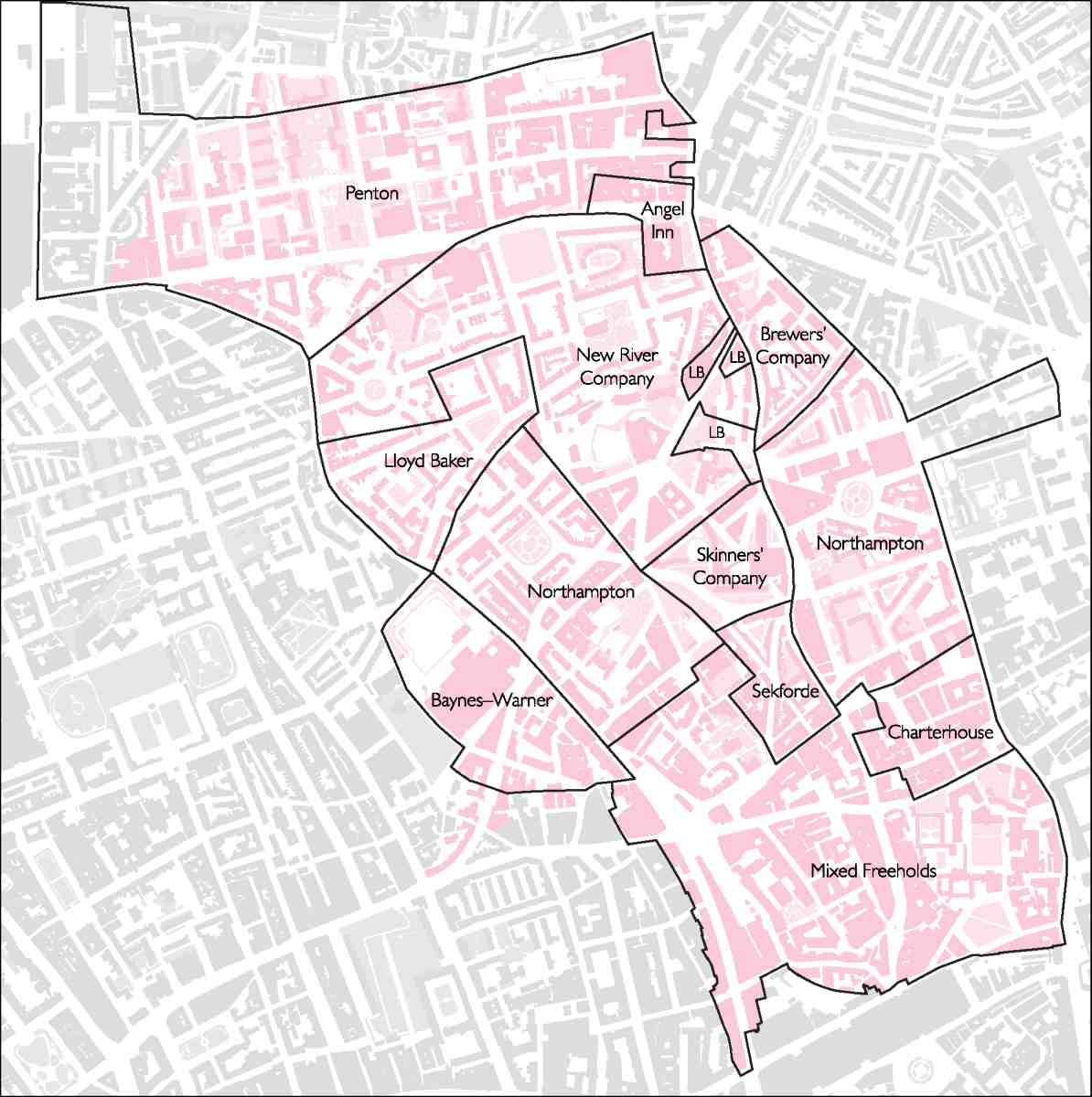

Pentonville began to make headway only in the 1780s. In the next decade the Northamptons stirred once more, appointing S. P. Cockerell in 1791 as a modern-style estate surveyor to oversee a fresh building initiative on their land. By 1800 it was plain that the parish's whole land surface would eventually succumb to the speculative builder. It was only a matter of time and timing before the major landlords of the intermediate zones, the Northamptons, Lloyd Bakers, and the New River Company, filled in the gaps. As always, development went in waves. The voids remained sizeable until about 1820, then quickly shrank. With the completion of the petite Seckford estate east of the parish church in 1840, central Clerkenwell was packed to the gills, leaving just a few stray green pockets further north (Ill. 4).

4. Principal landholdings in Clerkenwell, c. 1800

From 1801 we have outline information for Clerkenwell's resident population and growth rate. (The following figures omit the extra-parochial buffer zone around Turnmill Street, Cowcross Street and Charterhouse Square.) Over the next two decades the parish's population leapt from 23,396 to 39,105, or by almost 60 per cent. The same increase of 8–9,000 persons per decade continued until 1851, when the total was 64,778. After that, numbers steadied for the rest of the century. The peak came in 1881, at 69,076, after which decline set in.

It is against the rampant jump in numbers during the first half of the nineteenth century that Victorian development and redevelopment must be set. By 1850 Clerkenwell's build-up was essentially complete. The era of its reclamation followed. For, with what seems lightning rapidity, swathes of this prospering suburb had degenerated into slums. Just as in Britain's early industrial cities, the fervour of enterprise and influx of people bequeathed also overcrowding, poverty and disease, at its worst in the southern areas of Clerkenwell and St Sepulchre's Without. The next fifty years saw a long labour of slums earmarked and cleared, sewers, roads, railways and model housing constructed, and institutions created—chiefly churches, schools and dispensaries. The process left Clerkenwell a healthier but harsher environment.

The titular authority that in theory had presided over this mushrooming of a suburban parish to large-town dimensions was ill-equipped to run it. That was the Clerkenwell Vestry. A symbolic change had taken place in the old heart of the parish with the rebuilding of St James's Church, long delayed, in 1788–92. Outwardly that reconstruction, carried out under a large body of trustees, strengthened the Vestry's prestige. In reality its secular remit was limited. Its most onerous function was to administer the Poor Law and run the parish workhouse, built in Coppice Row in 1727, until Clerkenwell joined the Holborn Poor Law Union in 1869. It also controlled lighting and scavenging, and set and collected the rates. But drainage and paving were managed by separate commissions, albeit ones on which vestrymen were prominent. Such open space as existed was mostly controlled by local trustees. An exception was Clerkenwell Green, which at a date unknown came into the Vestry's ownership.

This want of wider powers and initiative, typical of Georgian parish government, became more problematic in the era of reform. After 1855 the Vestry—by then housed in the old watch-house in Rosoman Street, site of the future Finsbury Town Hall—took over paving, and acquired responsibilities for public health and sanitation. The opening salvo in the official campaign to clean up Clerkenwell came indeed in the form of a report of 1857 from the Vestry's first Medical Officer of Health, J. W. Griffith. (fn. 17) But the cleansing and reshaping of infrastructure were almost wholly carried through by outside bodies with larger capital at their disposal than the Vestry could raise: the City Corporation, the Metropolitan Board of Works, the Metropolitan Railway, and latterly the London County Council.

In one area of sanitary reform where the Vestry had authority to act, that of building baths and wash-houses, there was talk of the kind of initiative that other parishes took in the early 1850s and again in 1873–4. (fn. 18) On neither occasion did it come to pass, leaving private enterprise to provide these facilities. Eventually, the Vestry did cast off its reputation as a haven for self-interested house-farmers. A later Medical Officer of Health, Dr Glaister, told Charles Booth's investigator in the 1890s that it used to be 'a "guzzling" body' but had improved. (fn. 19) It picked up early on public library legislation and built its own library in 1890, while in its last years it anticipated the Local Government Act of 1899 by building an ample new vestry hall on Rosebery Avenue (1893–9) for its successor body, Finsbury Council, to inherit.

Slum-clearance and road-building go together in the politics of Victorian London. But in Clerkenwell road–planning had been bruited years before there was an explicit policy of using it to wipe out slums. First among these schemes was the line of Farringdon Road. Talk of improving north—south communications, recurrent in London planning, went back to the 1760s when the simultaneous making of Blackfriars Bridge and the New Road pointed to a link between them along the course of the polluted Fleet. With the City Corporation at the helm, the road had got as far north as Holborn Bridge in 1832, but then got stuck for want of Middlesex county funding. Though the northern trajectory of Farringdon Road was finally fixed in 1848, very limited progress had been made north of the City boundary.

What galvanized activity was the arrival of the Great Northern Railway at King's Cross in 1850 and the proposal, buttressed by City interests, to take a branch down the Fleet Valley to Smithfield and into the Square Mile. The destiny of Farringdon Road now became bound up with that of the Metropolitan Railway and with the City Corporation's resolve to rebuild Smithfield Market on modern lines, create a new live cattle market outside the built-up area at Copenhagen Fields north of King's Cross, and connect the two by rail. The Metropolitan Cattle Market (later the Caledonian Market) opened in 1855. Clerkenwell was thus ground for the first time between urban forces to its north as well as its south.

The vast and perilous road and railway works finally took place between 1860 and 1864, disrupting the whole western edge of the parish. Many were cleared from their homes, while jobs were affected by the relocation and rebuilding of the markets. Perhaps 5,000 were evicted, though critics put the figure at ten times that number. (fn. 20) The whole process was carried out under the aegis of the City Corporation and the railway company, heedless of local interests. Under the same joint management, the Metropolitan Railway was prolonged soon afterwards from Farringdon to Aldersgate (now Barbican), underground sidings were created beneath the new Smithfield Market (opened in 1868), and the City's new Charterhouse Street (completed in 1874) sliced into the enclave of Charterhouse Square.

Two further major Victorian roads were driven though the parish, by now under the Metropolitan Board of Works and London County Council—on which bodies Clerkenwell was at least represented. Though less drawn out and laborious than Farringdon Road, which they crossed, Clerkenwell Road (1874–8) and Rosebery Avenue (1887–92) were disruptive enough. Both belonged to lines of communication stretching beyond the parish. By the time of Clerkenwell Road, aiming a road at a slum—usually the cheapest property for compulsory purchase—was an explicit tool of social policy. So the opportunity was used to eviscerate the 'Little Hell' slums at the top of Turnmill Street and Britton Street, missed by the less pointedly reformative Farringdon campaign. The destruction wreaked by these routes was not confined to slums. Clerkenwell Road smashed through from one side of historic St John's Square to the other. Rosebery Avenue, partly built up on a viaduct, proved rather less damaging.

Parts of the urban fabric razed by these 'improvements' had been in sore plight for centuries. The Elizabethan notoriety of the courts off Cowcross and Turnmill Streets has been mentioned. By the mid-Victorian years conditions had greatly worsened, as old wooden houses became dilapidated and industrial intensification drew in population. The first clearances drove slum dwellers, reluctant to travel far, into a smaller compass. The number of residents per house in Clerkenwell parish rose from 8.6 in 1841 to 10.6 in 1871. (fn. 21) Meanwhile as the road programmes took shape, the spotlight of religious, medical and environmental investigation was turned upon these slums, now mingling condemnation with pity and calls for reform.

The Little Hell or Jack Ketch's Warren area at the top of Turnmill Street was one much visited by enquirers. This area had formerly been known for its low-life attractions such as bear-baiting and cock-fighting, drinking, gambling and prostitution. It had then been on the edge of London, with spas and pleasure-gardens near by, but was now deeply embedded in the urban matrix. Drainage, sanitation and water-supply were abysmal. A single water-closet in a court typically served all the inhabitants. In 1861 Rose Alley had just one between a hundred and sixteen people. (fn. 22) Water might be kept in the courts in casks or cisterns, but these were often cleared away, probably as an anti-cholera measure; instead there might be a standpipe, the supply being turned on for a short while each day. Those cisterns remaining were often broken or too filthy for use.

Occupants of such courts were mostly scraping a living. Many were chimneysweeps, who sometimes stored soot in the houses themselves. Most inhabitants, however, were costermongers, selling poor-quality vegetables, fruit, flowers, or fish. The donkeys that pulled barrows and carts also lived in the courts, often occupying the groundfloor rooms, even the kitchens. The missionary Thomas Nisbett described Turk's Head Yard as 'like a large uncleaned stable'. (fn. 23) In Frying Pan Alley, visited by George Godwin in 1853, the two rooms of a typical tenement were occupied by an old Irishwoman and her son, and a collection of women, children and lodgers, so that together twenty-five people slept there. In the lower room broken windows were stuffed with rags and rubbish, and there was no furniture except a backless chair and a broken bedstead. In the room above was no furniture at all. Meagre possessions and bottles of holy water hung from the ceiling, and the floor was strewn with bits of bone and iron and cinders for the fire, picked up in the street. (fn. 24)

The delinquencies in this nest of slums were detailed by R. W. Vanderkiste, for some years a missionary at a ragged school in Lamb and Flag Court, opened in 1845. He spoke of extreme ignorance and drunkenness, a culture of theft, particularly shoplifting, street-fights amongst both women and men, and the stoning and pelting of the police. Much of the problem he attributed to alcohol, pointing out that establishments selling drink matched in number shops where food was sold. (fn. 25)

Though these particular slums were swept away for Clerkenwell Road, a smaller nexus further east, centred on Jerusalem Court and Aylesbury Place off St John Street, endured longer. St John's Church nearby was frequently broken into, its roof stripped of lead and its incumbent on one occasion in 1902 assaulted and robbed—'a most unusual occurrence for a Clergyman to be robbed at Mid-day in the centre of his parish', he lamented. (fn. 26)

In The Nether World (1889), his novel of Clerkenwell slum-life, George Gissing eloquently articulated the juxtaposition of abject poverty with intensely productive craft-industry:

Go where you may in Clerkenwell, on every hand are multiform evidences of toil, intolerable as a nightmare. It is not as in

those parts of London where the main thoroughfares consist of shops and warehouses and workrooms, whilst the streets that

are hidden away on either hand are devoted in the main to dwellings. Here every alley is thronged with small industries; all but

every door and window exhibits the advertisement of a craft that is carried on within. Here you may see how men have multiplied toil for toil's sake, have wrought to devise work superfluous, have worn their lives away imagining new forms of weariness. The energy, the ingenuity daily put forth in these grimy burrows task the brain's power of wondering … Workers in metal,

workers in glass and in enamel, workers in wood, workers in every substance on earth, or from the waters under the earth, that

can be made commercially valuable. In Clerkenwell the demand is not so much for rude strength as for the cunning fingers and

the contriving brain. The inscriptions on the house-fronts would make you believe that you were in a region of gold and silver

and precious stones. In the recesses of dim byways, where sunshine and free air are forgotten things, where families herd together

in dear-rented garrets and cellars, craftsmen are for ever handling jewellery, shaping bright ornaments for the necks and arms

of such as are born to the joy of life. Wealth inestimable is ever flowing through these workshops, and the hands that have been

stained with gold-dust may, as likely as not, some day extend themselves in petition for a crust. In this house, as the announcement tells you, a business is carried on by a trader in diamonds, and next door is a den full of children who wait for their day's

one meal until their mother has come home with her chance earnings. A strange enough region wherein to wander and muse. (fn. 27)

The plight of Clerkenwell's working classes was among the reasons for the proliferation of its places of worship.

Up until about 1830, the established church and other denominations stressed a moral, middle-class discipline.

Dissent had been strong since the Commonwealth—witness the Peel Court Meeting House, a Quaker congregation established in St John's Lane in 1655, and a Baptist Meeting House of 1669 in Glasshouse Yard. The Spa

Fields Chapel, converted for worship from a failed pleasure palace in the 1780s, became the London headquarters

of the high-minded Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion. The flurry of nonconforming chapels erected between

1819 and 1835 was largely of the old 'respectable' type. They included the Claremont Chapel (Congregational),

the Spencer Place Chapel (Baptist), the Chadwell Street Chapel (Calvinistic Methodist), the Free- Thinking

Christians, St John's Square (Unitarian), the Woodbridge Chapel (Calvinist) and the Northampton Tabernacle,

Amwell Street (a Countess of Huntingdon offshoot). But the establishment in 1835 of a mission in Red Lion Street

showed awareness of the need for an alternative.

The Church of England changed its tack around the same time. After St John's had been revived in the 1720s, the next subsidiary outpost of the established church was the Pentonville Chapel of 1787–8 (later St James's, Pentonville). A neat chapel of ease with allocated seats, it had a history of difficulties, failing to adapt when Pentonville succumbed to late Victorian squalor. Next in line were the government-subsidized St Mark's, Myddelton Square (1825–7) and St Philip's, Granville Square (1831–2), likewise built in developing areas of the parish planned to be solidly middle-class. But the district around St Philip's never met expectations; soon a Tractarian incumbent was introducing the ritualism that some hoped would draw in the working classes. Like the Pentonville Chapel, St Philip's declined with its environs. It never attained the fashionable-slum-church reputation of its offshoot, Holy Redeemer, Exmouth Market (1887–95), boldest in architecture and ritual among Clerkenwell's High Church foundations.

In the climate of parochial subdivision from the 1840s onwards, Low Church incumbents took various lines. To counter the infidelity and immorality he perceived in Pentonville, the tactless Rev. Anthony Courtenay embarked on St Silas's, Penton Street (1860–3) without due funding or heed for building regulations and came to grief. More circumspectly, the promoters of St Peter's (1869–71), scheduled to serve an impoverished section of the Northampton estate, managed to harness to their cause Protestant enthusiasm and funds for a Smithfield Martyrs' Memorial.

Other clergy appreciated that in slum conditions schools and welfare must come before worship. Such was the Rev. William Rogers of St Thomas's Charterhouse (1841–2), a church with a parish in desperate straits (situated mostly east of Goswell Road in the Barbican and so beyond the limits of these volumes). On taking up his charge in 1845, Rogers put the founding of successful schools before his dour church's embellishment. On similar lines, when a new St Paul's parish was contemplated for the Great Sutton Street area in 1860, a school came first, the church following on later a short distance away.

By the nineteenth century the Clerkenwell area's main endowed charity schools, the Charterhouse School and Dame Alice Owen's School, had become middle-class. After the Endowed Schools Acts of 1869–74, both were reformed and rebuilt on an enlarged scale. Meanwhile the churches and chapels had to take the lead in educating the poor. The Clerkenwell Parochial Schools, originally situated in Aylesbury Street near the parish church, went back to 1700. They were drawn into the Church of England's 'national system' in 1815, when numbers rose from 100 to 280. But the state of the children soon gave cause for concern: 'notwithstanding these great exertions the Governors have still to lament the want of Clothing experienced by many of the additional Children whose Parents are in such poverty as to be scarcely able to furnish them with sufficient clothing to appear at the School'. (fn. 28) A move followed in 1830 to purpose-built premises in Amwell Street with a capacity of 1,000 (though the initial enrolment was only half of that). On similar lines, Pentonville created a small parochial school in 1788, then moved the boys into new premises in 1811.

There were various alternatives to the parish schools, institutional and private. Amongst the more formalized was the Welsh School, which built and tenanted what is now the Marx Memorial Library on Clerkenwell Green between 1738 and 1772. A purely secular education was certainly available. In 1808 a Pentonville Sunday school was set up on the grounds that small shopkeepers and tradesmen tended to send their children to 'the petty seminaries in their immediate neighbourhood' where religious instruction was not offered. (fn. 29)

The forty years between the opening of the Amwell Street school and the founding of the School Board for London in 1870 saw further church- or chapel-affiliated schools spring up, as well as several transient ragged or night schools. That these did not meet the demand or the preferences of the poor is suggested by the resources the early School Board devoted to Clerkenwell. Two schools, Eagle Court and Bowling Green Lane, both of 1873–4 and for some 800 children each, were among the most significant the board built; indeed Eagle Court featured in E. R. Robson's textbook School Architecture as an earnest of the board's programme for combating ignorance in the slums. Even before them, the board had embarked on the Winchester Street (now Winton) School in another deprived patch of the parish, its north-west corner. More assertive schools followed. A high point was reached with the landmark Hugh Myddelton School (1891–3), within sight of the board's earlier Bowling Green Lane. Opened by the Prince of Wales, it was a consciously symbolic replacement for the old House of Detention. Clerkenwell Close was confirmed as a School Board fiefdom when in 1895–7 its large central stores opposite, now the Clerkenwell Workshops, were also raised here, tricked out like its schools with the board's decorative entrance legends.

In the years before its downfall in 1904, the School Board extended its remit at schools like Hugh Myddelton to practical subjects like cookery and needlework. But perhaps the most sympathetic attempt at balancing education, missionary work and employment was privately provided, by the Watercress and Flower Girls' Christian Mission. Founded by an artisan, John Groom, and carried on from Sekforde Street, this refuge offered employment in artificial flower-making from the 1870s for disabled girls and women.

For an area dubbed by one mid-Victorian commentator 'a second edition of Birmingham, in as much as its leading branches of business are purely of a metallic character', (fn. 30) elementary education could hardly suffice. Yet for years few London industries saw the need to teach technical training. Clock- and watchmakers were the first to stir. Their British Horological Institute, founded in 1858, was based in Northampton Square, around which their skills had been densely present from the district's early years. When London polytechnics took off in the 1890s, the fine metal-working trades were again those best represented close by in Clerkenwell's contribution to the movement, the august Northampton Institute in St John Street (1894–8), now headquarters of the City University. Many other industrial skills were taught there. Swimming baths and a gym too were included, since the early polytechnics offered recreation for the working man (and, sometimes now, woman) as well as technical training.

***

Foremost among social needs was better housing. The sites freed up by Clerkenwell's official slum clearances were mostly taken up by warehousing and industry, while many further dwellings vanished as industry effected piecemeal demolitions of its own.

Though lower densities and more open space were the desirable ideal, fares were too high for working people to live far from their jobs. The fall-back position was to build 'model dwellings'. A clause in the Clerkenwell Improvement Act of 1851, which conferred power for completing Farringdon Road upon the City Corporation, permitted it to build 'improved Dwelling and Lodging Houses for the Poor … and to let the same … to such Labourers, Mechanics, and other poor Persons, at such weekly and other Rents and upon such Terms and Conditions as they shall see fit'. (fn. 31) This appears to have been the first parliamentary sanction for any local authority to build such housing.

Like many schemes for model dwellings, a first attempt to implement the clause in 1855 (before the Farringdon clearances) on a site in Turnmill Street collapsed in the shortfall between affordable rents and the cost of construction. A decade later the City Corporation succeeded in erecting Corporation Buildings, Farringdon Road (1864–5). Technically the country's first 'council houses', in plan and rules of tenure these flats followed on from blocks like Cobden Buildings, still extant in King's Cross Road (1864–5), erected for Sydney Waterlow and his private charitable trust, the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company. Next another company, the Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes, took up the torch with the bigger, even more barrack-like Farringdon Road Buildings of 1872–4. Neither of these historic pioneers of flatted housing for Victorian artisan families survives, nor are they regretted. If they did their job and were seldom short of tenants, they were never loved; in The Nether World, Gissing singled out Farringdon Road Buildings for crushing the human spirit. The only such group to remain in their immediate vicinity is the later Pear Tree Court development by the Peabody Trust (1883–4), built as so often for artisans in place of a nest of unhealthy slums occupied by the indigent poor.

By then a rough and ready system had been devised for model housing in central areas of London: clearance on local-authority application, followed by sale of the site to a low-profit company that then built the dour blocks. It was the local MP, W. T. M. Torrens, who sponsored the Artizans' Dwellings Act of 1868—proof enough that Clerkenwell and St Luke's (the two portions of Torrens's Finsbury constituency) then lay at the heart of urban housing politics.

During the 1870s attention shifted to the Northampton estate. Here as a first step the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company erected Compton Buildings (1871–7), Compton Street. A competition held in that connection proved only that 'architecture' could not alleviate such artisan flats. Indeed the later portions of Compton Buildings rose from five storeys, usually deemed the limit for walk-up flats, to seven. The Northampton property was plagued at this period by unscrupulous speculators buying up the ends of leases and cutting up houses into crowded tenements. The Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes (1884–5) scrutinized this particular estate closely. Critical of landlordism and vestry management alike, the Commission's report paved the way for change.

The advent of the London County Council (1889) and the Housing of the Working Classes Act of 1890 were followed by the vestries' abolition in 1900. As a result Clerkenwell entered the era of public housing locked with the even more impoverished parish of St Luke's as the borough of Finsbury. Not until the 1920s did Finsbury Council find the will and the wherewithal to build housing itself. But once embarked on that path, it waxed ambitious. Since the most important initiatives took place in northern Clerkenwell, this later phase in housing is reserved for the introduction to volume xlvii.

***

The 1870s and 1880s were boom years for Clerkenwell industry, even though the population was levelling out and the wealth generated mostly left the parish. Intensive commercial rebuilding took place, and not just on the road-clearance sites. Cowcross Street, for instance, shot up in scale and rid itself of most of its old houses and courts, as commercial tenants profited from the passenger and freight depot at Farringdon Station. St John Street likewise renewed itself with warehouses, as did Bowling Green Lane and other streets.

But the new thoroughfares led the way. The value of the improved road system was demonstrated when in 1887 the Post Office chose the old Middlesex House of Correction's big quadrilateral at Mount Pleasant for its new London sorting office. Close to Farringdon Road's intersection with the planned Rosebery Avenue, the site was perfectly placed between the City and the northern railway termini. The vast sorting office developed into the district's biggest employer. As for the types of buildings along the new roads, in Farringdon Road the purpose–built and therefore more individual premises tended to be the earlier ones, some touched with Gothic flamboyance. Later the frontage filled up with rows of speculative workshops or warehouses, modern-looking in design because so basic, maximizing window and floor space and often let by the floor. Similar blocks can be found in Clerkenwell Road and in Charterhouse Square, where the incursion of Charterhouse Street superimposed an industrial layer on to the palimpsest of the old precinct.

The manufactures carried on in these factory-warehouses varied immensely. The old strengths of clockmaking, jewellery, instrument-making and printing were at first reinforced, bringing with them ancillary trades. A few clockmakers were now able to centralize their manifold processes under single ownership in one or a few large shops. Long-lived examples include John Smith & Sons, a concern that started in the 1830s as makers of clock and watchglasses, soon took in other skills, built itself a three-storey factory, and persisted in St John's Square till the 1980s, albeit latterly as a metal engineering firm; and Thwaites & Reed, specialists in turret clocks, who after more than a century in Rosoman Street transferred in 1880 to premises behind Bowling Green Lane, staying till 1974.

Yet the generality of the watchmaking trade was now tipping into decline under pressure from cheap and deft foreign competition. By 1895 there could be headlines about 'A dead Industry'. 'Hand-made watches are things of the past', a lecturer told the British Horological Institute. 'The trade is dead; is buried. The body—the substance— is gone; the soul—the shadow—only remains. From an industry it has now become a fad'. (fn. 32) Despite that epitaph, Clerkenwell watchmaking survived, if increasingly confined to repairs.

The printing trades fared better. They had broken out of their St John's Lane and Square enclave before 1850, seeping into Clerkenwell Green. There they tightened their grip, until they occupied a third of the premises in 1939 and no less than a half in 1946. Most of these operations were small. But the clearances allowed the industry to spread further and raise big factory-warehouses. Some of the biggest belonged to printers' engineers who founded type or made and repaired presses. Such were the Farringdon Road and Ray Street premises (1864–8) of James Figgins, a firm that moved up from Smithfield when that area was cleared for the new market.

The nature of Victorian printing in Clerkenwell was miscellaneous, ranging from periodicals like General Booth's War Cry to engravings (whence the copious local presence of artist-engravers), maps, books, pamphlets and ephemera. Few premises seem to have been directly linked with the national or London-wide daily press. An exception is the fine warehouse at No. 16 Bowling Green Lane, built for the Standard group of newspapers, then based off Fleet Street in Shoe Lane.

If any one trade carried the torch for Clerkenwell's later radical politics, it was printing, not watchmaking. After the tense Spa Fields years, Clerkenwell Green bedded down in the more orderly working-class politics of Victorian London as a 'modern Agora' where the Corn Laws, Chartism, the suffrage and socialist revolution were successively debated. Over time various left-wing parties and newspapers were drawn in to the district, from William Morris's Socialist League to the Daily Worker. At the height of their respective influences in the 1880s and 1950s, both occupied addresses in Farringdon Road, testifying to the bond between printing and leftist politics. Some might claim The Guardian, in Farringdon Road at the time of writing (though not for much longer), as the last link in the chain. A more explicit if much mythologized heir is the Marx Memorial Library, the former schoolhouse on Clerkenwell Green where Lenin once corrected proofs for Iskra. Another token of down-market intellectualism were the Farringdon Road bookstalls, a feature of the area from 1869 to 1992, second-hand books being for a time supplemented with 'tools and wireless components'. (fn. 33)

There were two other leading industries in the later Victorian period, both spin-offs from City activities. The meat trades had always colonized the southern districts. But the building of the dead-meat market at Smithfield, the transport revolution and the coming of refrigeration transformed them. From the 1890s cold stores proliferated. They soon became large and intrusive, displacing many small meat and poultry dealers. In the drab decades after the Second World War only the printers rivalled them in number. Removing the trade in live animals did not end nuisance and pollution. Improved refrigeration was accompanied by a surge from the 1880s in the number of stoves for bacon-curing. They clustered at the south end of St John Street and in Cowcross Street, as well as along the City frontage of Charterhouse Street opposite Smithfield Market.

Clothing, the other major Victorian incursion, trickled north and west from the wholesale City warehouses of Cheapside and Wood Street to reach up both sides of Goswell Road. Artificial flower-making and mantle-making for City concerns had for some time been a common home occupation for poor women and children throughout the parish, but the scale of dressmaking now became industrial. From the 1860s much of Charterhouse Square was taken over by modest private hotels and staff hostels for labour-hungry clothiers. One such firm redeveloped the square's south side as a speculation in the 1870s, while in the twentieth century the hat manufacturer J. Collett Ltd took over much of its south and west sides, rebuilding the latter as its own premises in 1956–62. So fast has been the decline since then that no trace remains of an industry secure of its local future after 1945.

To focus on clockmaking, printing, meat and clothing is to miss Clerkenwell's array of manufactures from the 1880s on. Plucking examples at alphabetical random, billiard tables, carriages, cathode-ray tubes, compasses, floor-cloth, gas and electrical meters, glass of many kinds, paper bags, pattern cards, pavement lights, pencils, photographic prints, picture-frames, saws, school and medical footwear, surveying equipment, tools, varnish, weighing machines and wire were all being made in the area. Then there were the firms that performed just one of many steps in a process: the electroplaters, glass-bevellers, japanners, metal-stampers, and so on. As to the number of those so employed, statistics by sector are lacking until the era of the metropolitan boroughs, when we have figures only for Finsbury—a composite of Clerkenwell and the smaller but no less industrialized St Luke's. In 1904 those in Finsbury working in metals totalled 3,204, in paper and printing 10,015, in food, drink and tobacco 6,021, and in clothing 3,979. Only in clothing did women outnumber men—by almost six to one. By 1907 employment in metals and clothing had risen substantially, while that in paper and printing had dropped slightly.

Among the most successful specialities from this phase was electroplating. In 1934 over four-fifths of London's shops specializing in plating were said to be in Clerkenwell, most of them 'small units employing between ten and fifteen persons, using small workshops in converted dwelling-houses or a rented portion of an antiquated factory. Slight development on factory lines has taken place, and some of these bigger organisations have moved to the outskirts of London'. (fn. 34)

That tallies with the belief that Clerkenwell's huddled industries 'played a crucial role in the development of London's modern precision and electrical industries', before exiting 'very rapidly to the suburbs, on certain favoured axes'. (fn. 35) A firm whose record supports that argument is that of Sebastian de Ferranti, which began producing electrical meters in Hatton Garden in 1883, then moved to Charterhouse Square in 1888. After diversifying into power-station equipment and 'bursting at the seams', Ferrantis migrated to Lancashire with its skilled instrument-makers in the later 1890s. (fn. 36) Other examples are the Synchronome Company, leaders from 1895 in the field of electrical master clocks for factory clocking-in, first located in Clerkenwell Road, later at Alperton, Middlesex; and Oppermans, gear-cutters at first for the watch and clock trade, later for the motor industry, who decamped from Albemarle Way to willesden between the wars. (fn. 37)

The long-term omens could hardly be favourable. If electric power and transport offered better suburban or provincial locations, skills were bound to leave Clerkenwell. Nevertheless, well beyond 1914 most rebuildings reinforced the district's commercial-industrial traditions, relying on those trades like jewellery and printing that needed to be close to inner London customers. Such was faith in industry as Finsbury's future that the Ministry of Health could remark in the later 1920s that the borough was 'really wanted for commercial purposes'. (fn. 38) By then, policymakers believed the best place for housing was in the suburbs. Londoners were voting with their feet, and being encouraged to do so. So strong was the trend that after gentle decline from 129,000 in 1861 to 101,000 in 1901, over the next thirty-eight years Finsbury's resident population collapsed to almost half—an estimated 55,000 in 1939. (fn. 39) Yet a year earlier the total number of those employed in productive industry in the borough was a whopping 66,556, more by over 20,000 than the next most industrialized London borough. (fn. 40)

Commuters made up the difference. In 1885 the incumbent of St John's, Clerkenwell, William Dawson, had already pointed to 'the anomaly that few of the workers dwell in the parish, and few of the dwellers work in it'. The railways had helped people 'to escape from the gloom of mid-London every evening, and to occupy the streets of houses which have been run up in Tottenham and other northern suburbs', leaving behind them labourers, charwomen and cleaners who did menial jobs in the City or docks but seldom in the parish. (fn. 41) In 1903 the lament was the same. Workmen's trains spirited the skilled artisans away, leaving behind the feckless poor, without regular occupation. (fn. 42)

***

Against that backdrop, Finsbury's local politicians began at last to fight for its dwindling resident population. In the past there had been grass-roots radicalism but few vestrymen willing to champion the locality. Now there emerged a fresh sense of local leadership, exercised through the mechanisms of socialist political parties, factions and unions. When Labour took control of the council for the first time in 1928, the local party's slogan was 'Work for Finsbury men'. Yet there could be little connection between Finsbury's inter-war leadership and Clerkenwell's artisan class, now that most of the latter had moved away. In the context of the 1930s Depression, the new breed of local politicians like Harold Riley and Chuni Lal Katial turned instead to alleviating the plight of the borough's unskilled population, much of it poverty-stricken, unhealthy, and trapped in old accommodation. As social objectives gained pre-eminence, some confrontation between housing and industry developed. In areas like Percival Street on the Northampton estate, the respective claims of workshops and housing were fought over.

After its first period in office (1928–31), Labour took firmer control of Finsbury Council in 1934 and embarked on a reform programme with a propagandizing zeal few London boroughs could equal. Lubetkin and Tecton, most politically and socially committed of inter-war modernist architects, were enlisted to give the programme and the borough a powerful public profile. Of the three municipal schemes devised for the borough by Tecton, all located within the old parish of Clerkenwell, only the Finsbury Health Centre (1937–9) could actually be built before the Second World War. Their two housing estates, the monumental 'Busaco Street', later Priory Green, and its smaller companion, 'Sadler Street', later Spa Green, were postponed as money was diverted to rearmament. The saga of the strenuously ambitious architecture invented by Lubetkin and his successors for northern Clerkenwell is told in volume xlvii. If these projects were at odds with the area's history and traditions, they were meant to be so. Tecton's wider 'Finsbury Plan' of 1939, for instance, was merely a sketch, a modernist pipedream without basis in political reality. But like the housing schemes it represented freedom, imagination, and the riddance of an outworn past.

The Second World War brought an exodus of population and work, bouts of bombing, and inevitable neglect. In the years after 1945 the people and the fabric of Clerkenwell were reduced to perhaps their lowest point. By 1951 Finsbury's population had plunged again, to a paltry 35,343. War damage was everywhere, but worst between the Charterhouse and Goswell Road (on the edge of the devastated Barbican) and in parts of Pentonville. The London County Council now enjoyed wider planning powers. But its vision for the area, though cognizant of industry, held out no clear brief for its renewal, except to augment open space and inhibit factory rebuildings as a means of reducing 'industrial congestion'. (fn. 43) In 1947 Finsbury still had much the highest percentage of its land devoted to industry of any London borough, 106 out of 587 acres in total, or 18 per cent. With many firms keen to move out to single-storey suburban factories, the LCC hoped in 1951 to reduce this to a mere 26 acres. (fn. 44)