An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the Town of Stamford. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1977.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface: Houses', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the Town of Stamford, (London, 1977) pp. l-lix. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/stamford/l-lix [accessed 26 April 2024]

In this section

Secular Buildings

Houses

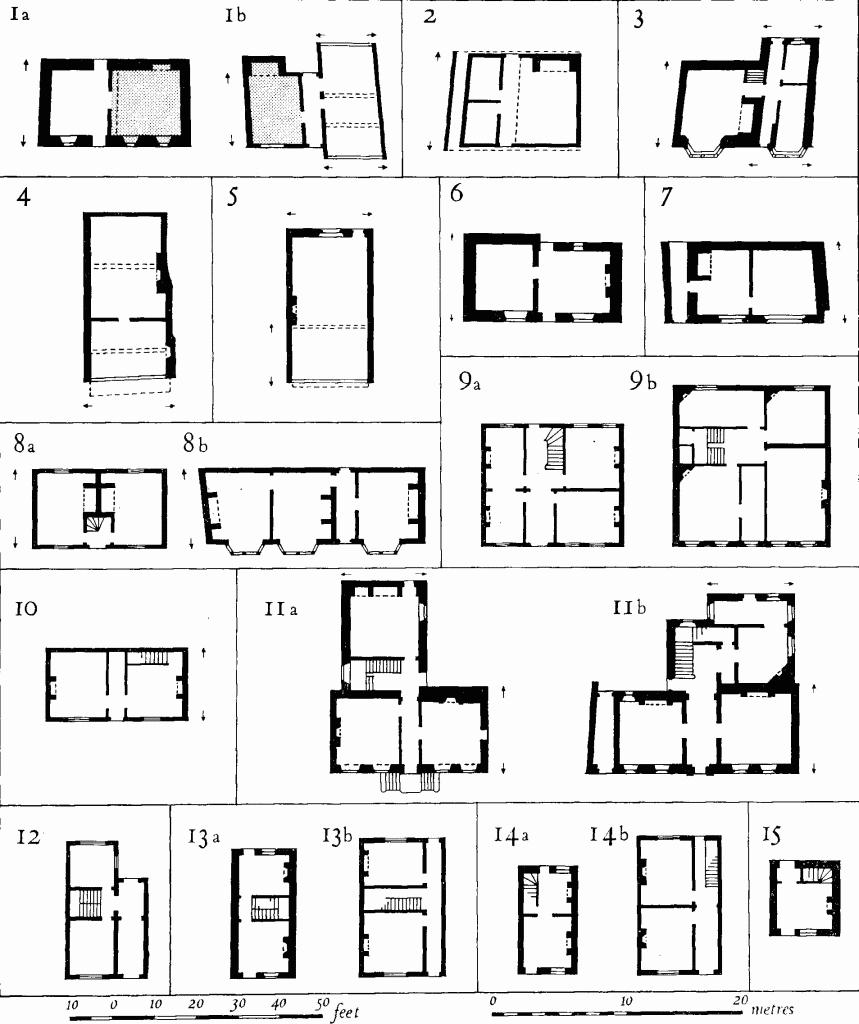

The different plan-forms found in Stamford have been classified (see Fig. 7) in order to help the reader to comprehend the range and development of houses in the town. This classification is deliberately broad, concentrating on general aspects of planning, and is not intended to have an application outside Stamford. Houses built before 1450 are usually too fragmentary to be included. Some houses fall outside the classification, either because only single examples exist or because of idiosyncratic design; others have been so altered that their original form cannot readily be determined. The classification can be summarized as follows:

Class 1. House having an open hall, and a storeyed end-bay roofed (a) in line or (b) as a cross wing.

Class 2. Storeyed house with hall and service rooms, the stack on the rear wall of the main room.

Class 3. Main range and cross-wing house, two storeys throughout.

Class 4. Two-room storeyed house, roofed at right-angles to the street.

Class 5. Two-room storeyed house, the front roofed parallel to the street, the rear wing at right-angles.

Class 6. Two-room storeyed house with stack at one gable end.

Class 7. Two-room storeyed house with entrance-passage behind the chimney stack.

Class 8. Internal-stack house with (a) two or (b) three rooms in line.

Class 9. Double-pile house, the stair rising (a) centrally in the rear half or (b) to one side.

Class 10. House with two rooms flanking a central entrance, the stacks usually in the gables.

Class 11. House with central entrance, the third room in a rear wing; the stairs are (a) in the body of the house or (b) in an angle-turret.

Class 12. Two-room house with rear wing, the stairs in the main range.

Class 13. Two-room house with central stairs, (a) without or (b) with an entrance-hall.

Class 14. Two-room house with stairs at side, (a) without or (b) with an entrance-hall.

Class 15. Single-room house.

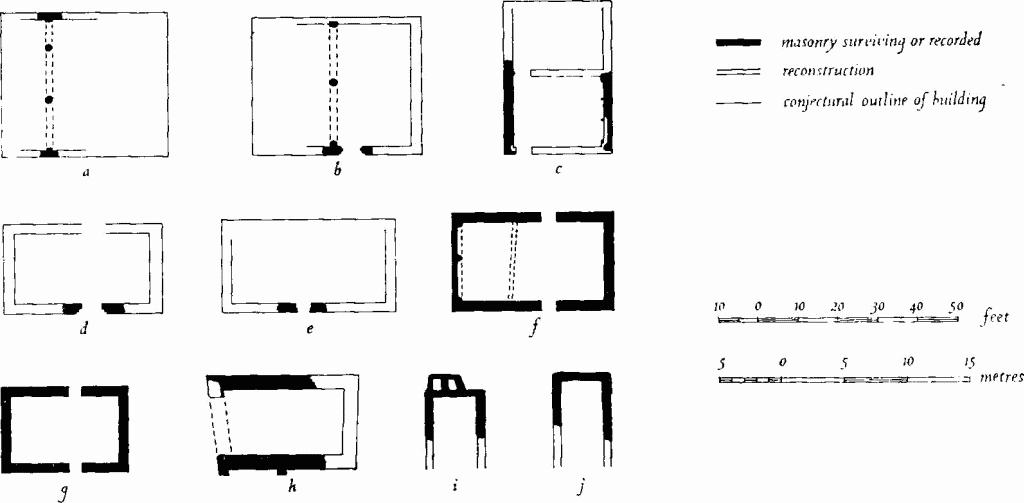

Fragmentary remains of several houses of the 12th and early 13th centuries survive in Stamford and others are known from early 19th-century drawings (Plate 61). The plain chamfered half-round arch continued in use into the early 13th century in this area, making precise dating difficult; for convenience such houses are referred to as belonging to the 12th century (Fig. 8).

Three houses have vestiges of what must have been ground-floor undercrofts. The evidence survives in the form of arcades, formerly open, of one or more bays and at right-angles to the street. In each building the evidence points to the absence of a vault, in which case the floor above would have been of timber. Two of these houses possibly had almost square plans. No. 10 St. Mary's Hill (336) appears to have had a two-bay arcade, and a length of about 35 ft.; the surviving 12th-century doorway of high quality to the N., and the evidence of further arcading to the S., suggest that the house occupied the site of 9 and 10, which have a combined width of 40 ft. In the late Middle Ages the N. half of this house was rebuilt as a range at right-angles to the street, perhaps reflecting the original roof arrangement. No. 9 St. Mary's Street (347) has a two-and-a-half bay arcade indicating a building 37 ft. deep, while the houses now adjoining, which might occupy the site of the original one, have a combined frontage of 42 ft. In both these houses the living accommodation must have been on the first floor. These large square houses of the 12th century have so far not been recognized in many other towns. Contemporaneous houses of similar size are Moyses Hall, Bury St. Edmunds; Norman House, Western Shore, Southampton; Jew's House and Aaron's House, Lincoln. The two examples from Lincoln are in ranges parallel to the street, whereas the two Stamford buildings, like Moyses Hall and the later Gysors Hall, Boston, appear to have been roofed at right-angles to the street. Aaron's House at Lincoln also differed in having a ground-floor open hall, whereas all the other buildings appear to have had the hall on the first floor.

The third house with a ground-floor undercroft, 17 St. George's Square (297), belongs to the 13th century. It differed from the others in being parallel to the street, 21 ft. wide overall and of uncertain length; with buttresses, string-course and eaves cornices, and a two-light window, it was clearly a house of high quality (Plate 61). An arch perhaps from a similar undercroft is rebuilt near 53 High Street St. Martins (232) and another was recorded as having been found in 1818 at the E. end of the S. side of St. Leonard's Street (Mercury, 12 May 1893). No. 15 St. Peter's Street (405), which appears to have a late 12th-century origin though almost totally rebuilt, is also parallel to the street but nothing can be said of its plan save that it was one room deep. The Horns Inn on the site of 12 Broad Street was a 44-ft.-wide building consisting of a single range parallel to the street, and having a near-central 12th-century doorway (Twopeny 290/b.1, No. 489); it was demolished in the late 19th century. The Ram Inn, 27 High Street St. Martins, before demolition in 1876, was also a single range about 40 ft. wide and parallel to the street; Buckler shows that it had a 12th-century doorway, 5 ft. wide and about 9 ft. high, near the centre of the elevation (Plate 61; BM Add. MS 24434 No. 79). The size of the opening invites comparison with that at St. Mary's Guild, Lincoln, which is similarly very large; this building has a ground-floor undercroft and apparently a first-floor hall.

Fig. 7 Classification of House Types.

The diagrams are based on plans of houses listed below, but later alterations have been omitted. Compartments shown with a stippled background denote halls open to the roof; small arrows indicate gables or hips of roofs.

1a. (103) 16 Barn Hill; 1b. (415) 35–36 St. Peter's Street; 2. (368) 40 St. Mary's Street; 3. (375) 12 St. Paul's Street; 4. (353) 17 St. Mary's Street; 5. (348) 10 St. Mary's Street; 6. (212) 23 High Street St. Martins; 7. (395) 7 St. Peter's Hill; 8a. (224) 41 High Street St. Martins; 8b. (224) 39–40 High Street St. Martins; 9a. (288) 8 Rutland Terrace; 9b. (246) 10 Ironmonger Street (first floor); 10. (242) 3 Ironmonger Street; 11a. (72) 3 All Saints' Place; 11b. (100) 13 Barn Hill; 12. (317) 4 St. Leonard's Street; 13a. (322) 18 St. Leonard's Street; 13b. (288) 17 Rutland Terrace; 14a. (117) 8 Belton Street; 14b. (288) 4 Rutland Terrace; 15. (171) 6 Gas Street.

Fig. 8 Plans of 12th and 13th-century houses.

a. (347) 9 St. Mary's Street; b. (336) 10 St. Mary's Hill; c. (338) 13 St. Mary's Hill; d. 27 High Street St. Martins (demolished); e. 12 Broad Street (demolished); f. (379) 16–17 St. Paul's Street; g. (378) 15 St. Paul's Street; h. (297) 17 St. George's Square; i. (16) former house in Water Street; j. (16) former house in Water Street.

No. 13 St. Mary's Hill (338) dates from the 13th century and retains an undercroft with original entrance and flanking windows, suggesting use as a shop. The undercroft is partly below ground level, and vaulted; the openings to the street are offset to the N. perhaps implying that the entrance to the house above was to the S. of the elevation. The building above was of two storeys and contained two rooms on plan, at right-angles to the street; communication between the rooms was apparently at the S. end. The ground-floor rooms were low, so the main rooms would have been on the first floor. The two 13th-century houses in St. Paul's Street (Nos. 14, 16–17) are the earliest survivors in Stamford to have had for certain ground-floor halls. No. 16–17 (379) had an open hall at the W. end, and perhaps a storeyed service and solar end to the E., though only the W. wall of the hall with its high quality blind arcading survives in recognizable form (Fig. 193; Plate 60). No. 14 (377) appears to have been similar, with its hall to the E. and with blind arcading, but here the hall also had an aisle (Plate 62). A third house formerly existed in Water Street, and was drawn in the 19th century by Twopeny (Plate 61; Twopeny 290/b. 2, pp. 42, 43). It had an open hall lit by traceried two-light windows, and was presumably entered by opposed doors. These houses would have conformed to class 1 (see p. liii).

No substantial remains of houses of the 14th century are now recognizable. The roof of an open hall at 25 High Street St. Martins (216) could be as early as the 14th century, but the surviving part tells us little of the building except that it lay parallel to the street; presumably it resembled the later two-cell houses of class 1 in the town. Houses built at right-angles to the street are now rare and are not easily interpreted. Most of the remaining houses of the 15th and 16th centuries consist of two units parallel to the street; sometimes one unit is built as a cross wing. The surviving houses were all of relatively high social class, and in the better ones accommodation was doubtless supplemented by additional buildings behind. Nos. 11–12 St. Mary's Street (349) has a courtyard at the back, though the ranges that surround it are now post-medieval. One proper courtyard-house survives, apart from fragments of inns, although the early 16th-century range behind 6 Barn Hill (95) must almost certainly have belonged to such a house. This courtyard-house, 69 High Street St. Martins (238), consists of three ranges, one of which contained an open hall. The plan is not clear, and it is possible to interpret it as two separate houses or tenements. The W. range had an open hall and a storeyed cross wing, separated by two passages with a chamber above; the E. range may have consisted on plan of two rooms also separated by an entrance.

A feature found in several houses of the 16th and 17th centuries is an entry at one side, usually 3 to 5 ft. wide, providing access to the rear of the premises independent of the house. These entries are particularly associated with urban houses, where a continuous frontage is an obstacle to access to the yard behind. In class 2 houses the entry can be at the hall end, as 9 St. Mary's Hill (335), or at the service end as 40 St. Mary's Street (368), while in class 4 houses it is of necessity at the end opposite to the cross wing, as at 20 High Street St. Martins (210). Goldsmiths Lane passes through such an entry at 33 Broad Street, a building which also has a carriage-entry, a much larger type of access which is now rare in Stamford and is today mainly associated with inns (as 33 Broad Street (144), 25 High Street St. Martins (216), 19 St. Mary's Street (355)). In the 16th and 17th centuries the word 'entry' was generally applied to internal passages, but was also used for foot-passages, for example in the list of fittings of Richard Snowden's house in 1582 (Ex. MS, 33/11) where the street end was closed by a gate with a wicket. They may also appear in probate inventories e.g. LAO 1641/17 (of 1641); 163/27 (of 1665); 182/351 (of 1667). The usefulness of entries has meant that many have survived to the present day. Despite remodelling they still exist at 31 Broad Street (141) and 34 St. Peter's Street (414). In some large houses of the 18th century side passages gave rise to some ingenious attempts to disguise an embarrassing asymmetry. Those at 19 St. George's Square (299) and Brazenose House (383) have gone, but they survive as monuments (100), (301) and (376).

Several 17th-century probate inventories of large houses and inns record 'gatehouses', for example in 1683 (LAO, 183/237). These presumably refer to the wide carriage-entries such as that at 19 St. Mary's Street (355); the Bull Inn (352) had one opening on to St. Mary's Street and a 'back gate' leading towards High Street. The first known reference to gatehouses is in the early 14th century, when a large tenement in Water Street is said to have had a solar at one end and a great gate at the other (PRO, E 315/37 no. 20). Several houses away from the centre of the town managed to obtain a rear access, often by a postern and entry as at Torkington House (417). No. 12 St. Paul's Street (375) is known to have had a rear access to its stables, and this was probably also necessary for the Norris' bell-founding business.

Class 1. Before 1500 most houses in Stamford had open halls, and were built in stone or timber-frame. The basic medieval plan is typified by 17 Broad Street (135), with an open hall at one end and a two-storey section at the other, all under a single roof and parallel to the street. This plan, class 1, is seen at 11–12 St. Mary's Street (349), where the storeyed service and solar end was rebuilt in ornate timber-frame in the late Middle Ages (Plate 70). At 16 Barn Hill (103), a 15th-century vicarage, the solar projects beyond the passage into the hall, where it is carried on a beam, an arrangement intended to give extra space at first-floor level on a restricted site (Fig. 82). One house, 21 All Saints' Street (82), was originally open to the roof throughout. No. 40 St. Mary's Street (368) dating from c. 1500 has a formal passage defined by walls, and two service rooms at the lower end. This house shares with 56 High Street (192) the curious feature of an asymmetrical roof, the first floor construction of (368) resembling a single-aisled hall (Fig. 185).

Open-hall houses in Stamford appear rarely to have had cross wings. At 28 St. Mary's Street (362) the storeyed end is roofed as a cross wing, though it does not project beyond the walls of the main range. No. 35 St. Peter's Street (415) has a full cross wing, and perhaps the W. range of 69 High Street St. Martins (238) could also be included. It is not clear whether 25 High Street St. Martins (216) had a cross wing before the 16th century. The large stone house formerly standing W. of monument (281), called Peterborough Hall by Stukeley when he made a partially conjectural drawing (Designs, 73; Plate 70), had an open hall and cross wing.

Class 2. There is no evidence among the surviving houses in Stamford for open halls being built after c. 1500. During the 16th and 17th centuries most of the existing open halls were floored over. Houses built during the 16th century in general followed the earlier plans, differing mainly in being storeyed throughout (class 2), but a larger proportion of these new houses had a cross wing (class 3). These houses are almost invariably of timber-frame. The chimney stack which heats the hall is generally on the rear wall, as at 8 and 9 St. Mary's Hill (334, 335), 9 St. George's Square (294) and 12 Water Street (442); exceptionally at 11 St. George's Street (304) it is placed on the front wall.

Class 3. The range and cross wing houses of class 3 often have their passage within the cross wing, as at 51 High Street (189) and 10–11 St. Paul's Street (374). The stack, generally against the rear wall, is sometimes placed between hall and cross wing so that it could heat both rooms, as at 20 High Street St. Martin's (210), 6 St. Peter's Hill (394) and 3 Austin Friars Lane (84). At 12 St. Paul's Street (375) it backs on to the cross passage. Both class 2 and 3 houses, being storeyed, may have a continuous jetty, as originally at 7 St. Paul's Street (372), 51 High Street (189) and 11–12 High Street (177).

During the 16th century class 1 houses were converted to classes 2 or 3 by the insertion of a floor in the open hall. No. 20 St. Mary's Street (356) was floored in the 15th century, and 16 Barn Hill (103) as late as the 17th century. Similar houses to classes 1 and 2 are found at Burford, Oxfordshire, where there are even fewer cross wings than at Stamford. Class 1 houses may be compared with Bull Cottage, Witney Street, and class 2 houses with the Highway Hotel, High Street (M. Laithwaite in Perspectives in English Urban History (1973) ed. Everett, 76, 78).

Class 4. All the houses so far discussed have relatively wide frontages. Houses built on narrower plots in the late and post-medieval periods were one room wide and of different plan. Two houses in Water Street (16) dating from the 13th century are known only from excavations (C. Mahany, Archaeology of Stamford (1969), 13–16); built at right-angles to the street, they had cellars and, at the rear, privies. Surviving houses of this class are hard to interpret in their present state. Nos. 17 and 18 St. Mary's Street (353, 354), both single ranges at right-angles to the street and probably of two-room plan originally, are houses which belong to this class; no. 18 has a crown-post roof over the back room.

Class 5. A more complex form, probably of higher social standing, is also found. These houses generally appear to have had two rooms on plan. The front is roofed parallel to the street, and behind is a wing which may occupy the full width of the house. The largest example is 56 High Street (192), which resembles a class 2 house with contemporary rear wing. The front range, however, is not very wide and possibly consisted of one room with a passage on the W.; the whole house therefore would have been of two-room plan. No. 20 St. Mary's Street (356) also seems to have consisted of a jettied range of single-room plan parallel to the street, and a rear wing of similar size; no. 10 St. Mary's Street (348), probably dating from the 17th century, has the plain rectangular form of class 4 but at present has two roofs at right-angles as in class 5, to which it should technically belong. At 5 St. Leonard's Street (318) the wing is also as wide as the front range; this too is an early 17th-century house. No. 14 High Street (178) has had its earlier part demolished, but appears to have conformed to class 5, with a rear wing containing a large stack. The 16th-century structure at 10 High Street (176) could be the rear wing of a large house of this class.

Only one early house, 9 St. Mary's Street (347), has two ranges lying parallel to the street. The original arrangement on the ground floor is not now recoverable, but the first floor had a single room in each range. Medieval double-pile urban houses generally had an open hall in the rear range, e.g. 20 and 40 Jordan Well, Coventry, and Tackleys Inn, Oxford (Med. Arch. VI-VII (1962–3), 221, 217). This Stamford house, storeyed throughout like 5 Pottergate, Lincoln, represents a further development of that plan, but it incorporates part of a large 12th-century house which may have affected its form.

There was a change in the plan-types of new houses in about 1600. Although the basic form of a twocell structure parallel to the street remained the same, internal planning was altered. A few houses of class 2 were built, perhaps including 11–12 High Street, and also class 3, including 7–9 Red Lion Street (285), but they are early and could even date from the late 16th century. Classes 4 and 5 also continued in restricted use.

Class 6. The first major change to take place c. 1600 was the abandonment of the lateral stack, hitherto used almost exclusively, in favour of axially-placed stacks, generally at one gable end of the house. The earliest internal stacks are those already noticed in class 3 houses such as 20 High Street St. Martin's (210) and 7–9 Red Lion Street (285), and also the possibly inserted stack at 12 St. Paul's Street (375) and 3 St. Peter's Street (398). The gable stack at 21 All Saints' Street (82) is exceptional.

The class 2 house developed naturally into class 6 by transferring the stack position to the gable wall of the main room. Entrance was still gained by a near-central doorway which could lead to a lobby, as at 26 Austin Street (91) of 1706, or to a central passage as at 30 St. Peter's Street (411) of c. 1650 and 1 Ironmonger Street (240) of the late 17th century. The stair could be in a separate compartment at the service end, as at the two last-mentioned houses, or beside the stack as at 30 St. Peter's Street.

Class 7. A less common plan has the stack backing onto a passage at the end of the building. The stack thereby becomes internal, the passage being not an entry but an integral part of the house and its only access. No. 7 St. Peter's Hill (395), built just after 1600, is the earliest example in Stamford; no. 23 St. George's Street (308) dates from about the middle of the 17th century. This plan-form, though nowhere common, has a wide distribution, being found as far distant as Sherborne (RCHM, Dorset I, Sherborne (60, 71, 99)) and at 27 High Street, Uppingham, Rutland.

Class 8. Axially-placed chimney stacks are characteristically placed internally in 17th-century rural houses but in Stamford they are usually built at gable-ends. Consequently two and three-cell houses with internal stacks have been grouped as a single class. Two-cell houses of this form (class 8a) originated in the early 17th century, and usually have lobby entrances and stairs against the stack (RCHM, Cambs. I and II, class I; H. M. Colvin in Studies in Building History ed. Jope (1961), 223). At 45 High Street St. Martins (227) the stack is built against the rear wall. This type of house remained common in Stamford until the middle of the 19th century, by which time it was only used for small dwellings. Three-cell houses (class 8b) are essentially rural buildings and their appearance in a town is noteworthy. Two are in St. Leonard's Street (319, 320); both are early and of timber-frame.

The end of the 17th century saw several fundamental changes in domestic planning in Stamford. A heightened sense of symmetry in external design had its counterpart in internal planning, and coupled with new ideas of room-use, culminated in the houses of the Augustan Age.

Class 9. The double-pile house developed in the late 16th century as a gentry-house, used at first for buildings such as Red Hall, Bourne, Lincs., of the early 17th century. This type of house, class 9, first appeared in towns about the middle of the 17th century, and in Stamford the earliest example is 19 St. George's Square (299), completed in 1674. Typically the stairs rise in the centre of the back range, and the entrance is directly into one room, the hall. The kitchen occupied the rest of the front range, and there seems to have been a principal withdrawing room at the front of the house on the first floor. In the early 18th century this plan was used for a pair of semi-detached houses of very high quality, at 66–67 High Street St. Martins (237). Brazenose House of 1723 (383) has a separate entrance-hall dividing the two front rooms, and this developed form is also seen at 20 St. George's Square (300). At Brazenose the kitchen is in a front room, but at 20 St. George's Square and also Barn Hill House (96) of 1699 a fall in ground level made it possible to put the kitchen in a basement.

In the 18th century a variation is found, which may be called class 9b, where the stairs rise on one side of the house between front and rear rooms. The earliest examples, 9–10 Ironmonger Street (246) and 18–19 High Street (180), have lost their original ground-floor arrangement, but 46 High Street St. Martins (228), built c. 1830, remains intact. This plan was always associated with large houses and remained in use into the 19th century (RCHM, Cambs. I and II, where it is Class U).

Class 10. The early post-medieval house represented by class 2, and in the 17th century by class 6, remained in use until the end of the 17th century at least. One of the latest examples, 1 Ironmonger Street (240), illustrates how this class 6 plan could be adapted to resemble a symmetrically-fronted house. Houses of class 10 (class T of RCHM Cambs. I and II) first appear in English towns about the beginning of the 17th century, and have two rooms flanking an entrance passage. Gable stacks are common but not universal. A symmetrical plan and elevation is normal, but the earliest examples in Stamford tend to be asymmetrical, as 11 Broad Street (132), perhaps indicating that locally the type developed from class 6. Houses of class 10 appear in Stamford and other nearby towns in the early 18th century, as in Oundle (RCHM, Monuments Threatened or Destroyed, p. 51), and only become common in the early 19th century.

Three further houses should be discussed at this point. All follow the same plan, although one (184) was converted from an older house. They are two rooms deep and six bays, or three rooms, wide and were built in the first half of the 18th century. On the ground floor a passage divides each house unequally, and in each case this also marks the division of the house into two dissimilar tenements, the larger of class 9 and the smaller of class 13. At 9–10 Ironmonger Street (246) the deeds show that this was the original arrangement, and that the owner lived in the larger house. The first-floor planning and fittings at 18–19 and 25–26 High Street (180, 184) indicate the same arrangement. Similar pairs are found in other towns, e.g. Witham, Essex (Post-Med. Arch. 6 (1972), 18).

The basic arrangement of two rooms flanking an entrance was not adequate for a large house in the 18th century, unless service accommodation was located elsewhere. At Austin House and 12 Austin Street (85, 87) it is provided in the ample basement, a device made possible by the fall in land. Basements of the metropolitan type were not common in Stamford, but some examples are found along the edge of the scarp above the flood-plain where a drop in level already existed. The usual expedient was to provide services in a rear wing.

Class 11. The provision of a rear wing produces a separate house-type, class 11. The stairs, instead of being in the body of the house, are either in the wing or in a turret in the entrant angle. Staircases in the rear wing probably occur first, as at 3 All Saints' Place (72) of the very early 18th century, but the arrangement of a turret in the angle of range and wing is convenient and occurs for example at 13 Barn Hill (100) of 1740. Houses of this class were always of high social standing and are usually of a good standard of architectural design. Several houses originally of this class have been altered in subsequent years. No. 18 St. George's Square was completely replanned and partly rebuilt in the early 19th century, and about the same time 21 St. George's Square was even more drastically altered, the rear wing being replaced by a second range parallel to the street (see below Alterations).

Class 12. An L-shaped house, smaller than class 11, developed during the 18th century and forms class 12. In plan the main range contains only one room, with an entrance-hall along one side opening out to a stair which rises behind the room. Service and other rooms are in a rear wing, reached usually from the stair hall. This plan, related to the standard terrace houses of the period, occurs in Stamford for houses of good social standing. It first appeared after 1750 in houses such as 25 St. Mary's Street and 13 Maiden Lane (359), and continued in use into the early 19th century.

During the 18th century two new house-plans appear, related to both metropolitan and provincial terrace houses. Two rooms deep and one room wide, they are entered at one end of the elevation.

Class 13. These houses were usually roofed parallel to the street. The first of this type to be found in Stamford, class 13, has its stair rising between the front and rear rooms. Occasionally it is found as a nonparlour house (class 13a) where the front room is entered directly from the street, but in Stamford most surviving examples are parlour houses (class 13b) where an entrance-hall separates the front room from the circulation of the house. Although the plan is found in other towns in the late 17th century, e.g. Taunton (Taylor, Post-Med. Arch. 8 (1974)) and Knighton (Woodfield, Trans. Radnor Soc. (1974)), it does not occur in Stamford until the early 18th century when it is used for semi-detached and terraced groups of high architectural pretension. Three such houses form 8–10 High Street St. Martins (206) and three houses of this class are paired with class 9 houses in grandiose semi-detached pairs (180, 184, 246). This type reappears in the early 19th century when it is used for terraced houses such as those in Adelaide Street. The problem of lighting the staircase of these houses was overcome in Adelaide Street (114) by continuing the stair well into the roof, where it is lit by a dormer window.

Class 14. The most common small house plan, class 14, has its stair in the rear corner of the house, opposite the main entrance, and in its simplest form is a non-parlour house entered directly into the front room (14a). At a higher social level there is a parlour and a hallway (class 14b). This plan-type makes a later appearance in Stamford than class 13, but both were adopted for the bulk of middle-class housing in Stamford in the early 19th century. Both classes 13 and 14 were used in Rutland Terrace (288) and class 14 was used for high-quality developments such as Rock Terrace (426).

Class 15. The small single-room house of class 15 existed from the earliest times but being of low social status only the 19th-century examples have, in general, survived to the present day. These were the houses of the labouring classes, and requiring little land were built on the encroachments around the edge of the town, such as North Street, along with small class 13 and 14 houses. This plan was also used for the small tenements built in back yards in the 18th and early 19th centuries, for example the 18th-century row behind 3 St. Leonard's Street (316). Some newel stairs winding alongside the chimney stack are to be found in Stamford houses of the 17th and 18th century, for example 26 St. George's Street (309), but in the 19th century most stairs rose along one wall. In a few exceptional cases this plan seems to have been used for larger buildings of importance, e.g. 1 St. George's Square dating from the early 18th century. Nos. 15, 16, and 17 High Street (179) must have had service wings originally but appear now to belong to this class.

Contemporary description of houses and their rooms

After c. 1600 contemporary descriptions of houses give a better understanding of how they were used. It is not possible to apply to these descriptions the same classification devised for standing buildings, and interpretation is further hampered by the incompleteness, for various reasons, of many descriptions. During the 17th century every house described in probate inventories had a main living room, called the hall, and most had a parlour. A few houses had two parlours, and some had three or more especially in the late 17th century. The main store room was called the buttery and is specifically mentioned in every house before 1681. After that date it was replaced, in name at least, by a pantry, although this room-name, first appearing in 1677, is only found in a quarter of all inventories. Before 1684 kitchens are named at about half the houses described, but their position is not clear; they become more common after 1700. The number of chambers recorded increased from an average of about two to each house in the first half of the 17th century to about three in the second half, the range increasing from between one and four to between two and five. Most buildings with more than five chambers were inns. Before 1684 about half of the inventories record shops, though their function and position in the building varies, several clearly being workshops in the yard behind the house. A characteristic two-room house with an entry at one end, presumably belonging to class 2, 6 or 7, was that of George Barlow; in 1689 it had a hall, parlour and entry each with a chamber over (LAO, 188/404). Another two-room house, which may have been of class 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 or 10, was occupied by John Neale; in 1738 it had a house (main living room) and 'other room', a best chamber and 'other chamber', garret and cellar (LAO, 210/115).

During the 18th century changes occurred in both the houses and the surviving descriptions. Inventories decrease in numbers towards the middle of the century, as newspaper advertisements increase. Advertisements generally describe larger houses of fairly high social standing, while inventories mainly apply to the lower strata of society; inventories attached to wills proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, which would correct the imbalance, are not yet available. As may be expected, the terminology of advertisements is more up-to-date than that of the inventories and this also reflects the relatively modernized condition of those houses. Similarly the conservative terminology of the inventories is also partly an indication of the slow rate at which new ideas penetrated down the social scale. The smaller houses described in the inventories prior to 1763 have a hall and parlour, usually a kitchen, sometimes a pantry, and two or three chambers, rarely more. The advertised houses, after 1733, are similar in accommodation, though with more chambers. Instead of a hall and parlour they have two parlours usually of equal status, and after 1773 one of these is sometimes called a dining room or drawing room. The change from hall to parlour probably implies the presence of a separate entrance lobby or hall as opposed to direct access to the room from the street.

Evidence for first-floor reception rooms is found only after 1770, though they clearly existed earlier (e.g. (299)). Where shops occupied much of the ground floor, living accommodation was commonly displaced upwards; Mrs. Taylor's shop in High Street in 1806 had a shop and kitchen, with dining room and bedroom above (Mercury 5 Sept.). Larger houses, not necessarily with shops, often had a drawing or even dining room on the first floor. An example of the changes in room-use between the 17th and 18th centuries is 12 St. Paul's Street (375) which was described in 1626 as containing hall, parlour, hall chamber, shop chamber, parlour chamber, kitchen chamber, kitchen and buttery as well as a workhouse and hay barn (LAO, 131/443). By 1742 a change in emphasis of room-use resulted in the house being described as having two parlours, a wainscotted hall, kitchen, larders, pantry, cellar, and six chambers, closets and a garret; outside there was a paved yard and a garden (Mercury, 2 Dec. 1742). An advertisement in 1786 described it as having three good parlours, kitchen, cellaring, three genteel bedchambers with closets and three good servants rooms. The garden now had a stable besides outhouses such as a brewhouse and wash house (Mercury, 1 Dec. 1786).

A class 10 house, 16 All Saints' Place (74), was described in 1793 as having a parlour, kitchen, pantry and scullery on the ground floor, and two chambers and a dressing-room on each of the upper floors (Mercury, 15 July). By 1817 one of the first-floor rooms was being used as a drawing room, with two parlours on the ground floor (Mercury, 10 Oct.). A smaller house of the same plan (169) had in 1822 a kitchen, a parlour, and two sleeping rooms above (Mercury, 3 May). No. 21 St. George's Square was probably a class 11 house before the rear section was rebuilt; in 1773 it had its kitchen, cellars and brewhouse in the basement, two parlours and a dining room on the first ground floor, and three chambers above (Mercury, 5 Aug.). A more characteristic arrangement is that of an unidentified house with two parlours and a kitchen on the ground floor, a drawing room and two chambers above, and three garrets in the roof (Mercury, 13 Sept. 1781). No description of a class 12 house has been identified, but 49 Broad Street (148) which resembles this plan had in 1792 a large dining parlour and kitchen on the ground floor, a drawing room and two lodging rooms on the first floor, and four further lodging rooms in the attic (Mercury, 2 Mar.).

The earliest bathroom and water-closet are those recorded at 23 St. Mary's Street (358) in 1814, the house of a wealthy merchant. Vale House (250) had a shower bath by 1823 (Mercury, 5 Aug. 1814, 5 Sept. 1823). Houses were sometimes sub-divided temporarily by forming a unit for letting; in such cases the kitchen, a room not easily improvised, was always shared. An early example is an unidentified house in High Street, where in 1778 the apartment had four lodging rooms and use of the kitchen (Mercury, 8 Oct.).

Alterations

The process of modernizing houses to meet current needs and concepts is a continuous one, and the main trends in Stamford may be briefly examined. The most common alteration during the later Middle Ages was to floor over an open hall to give a two-storeyed building. In this way class 1 houses were converted to class 2 or 3 in the course of the 16th century, and probably some open halls remained to be floored over in the 17th century. This was done at 28 St. Mary's Street (362) in the 16th century, and at 25 High Street St. Martins (216) about the same time (Plate 71). A further modification of class 2 and 6 houses was made, often during the 18th century, which converted them from sub-medieval houses, entered directly into the main living room, to more convenient class 10 houses with rooms protected from the door by an entrance hall. This modernization is well documented at 23 High Street St. Martins (212) where a lease specifies the insertion of a new wall and removal of the stairs to a more convenient position (Ex. MS, 88/52). By providing a new stack in the former service room and perhaps moving the original hall fireplace to a new position on the other gable, houses of classes 1, 2 and 6 could easily be converted and almost completely disguised.

The simplest and most usual way of enlarging houses in Stamford was to add a rear wing. This was done at 55 High Street (191), at 12 St. Paul's Street (375) in c. 1600, and, later in the 17th century, at 40 St. Mary's Street (368). Commonly the wing was added behind the hall only, as at 12 St. Paul's Street, a class 3 house. The reason for this is clear for an addition to a cross wing would mean the exclusion of light from the rear room of the cross wing. Presumably the same reason would apply to those class 2 houses where there were two service rooms. Nos. 11–12 St. Mary's Street (349) and 35–36 St. Peter's Street (415) have the same improvement. Enlargement by building detached blocks, as happened in some other parts of England, is rare in Stamford where a rear wing along one side of the plot was the normal method of extending a house.

The other method of enlargement employed in Stamford in the 17th century and later was to build a rear range parallel to the front range, doubling the depth of the house. Nos. 11–12 High Street (177) was a class 2 house enlarged in this way probably early in the 17th century. This can be seen in the 19th-century alterations at 21 St. George's Square, where the final plan is almost that of a class 10 house. Houses of class 10 and 11 were sometimes enlarged and given more spacious accommodation by a process that also destroyed the symmetry of the elevation, and produced a plan similar to class 9. The central entrance hall and one flanking room were thrown into one; the main doorway was moved to the nearest window-opening of the other room which in turn became a spacious entrance hall (Fig. 149). This also necessitated the rearrangement of the back parts of the house. Most examples seem to date from the early 19th century, such as 38 High Street St. Martins (223) and 18 St. George's Square (298) (Plate 113). No. 15 Broad Street (134) was probably altered during the middle of the century.

Only rarely does extra accommodation appear to have been gained by heightening, except by raising the front wall of an attic or first floor to improve head room, as at 1 Broad Street (126) and 17 Barn Hill (104). Generally an increase in height accompanied almost total rebuilding, as happened at 54–55 High Street (191) and 25–26 High Street (184). The principal exception is 19 High Street St. Martins (209), though the amount of internal reconstruction appears to have been more than originally envisaged (Ex. MS, 88/51).

As fashions changed and the fabric of houses came to need refurbishing, buildings were modified externally to conform to new canons of taste. Stone-mullioned windows often had one or more mullions removed to give a larger glazed area, and in the 18th and 19th centuries sash windows were inserted in place of the older types. The walls of timber-framed houses were commonly encased or replaced in stone. Sometimes this only involved replacing the lower stage, beneath a jetty or bressummer, as at 20 High Street St. Martins (210) and 35–36 St. Peter's Street (415). Usually the walls were built against the line of the outer face of the original frame, necessitating an extension of the roof; the resulting change in pitch two feet from the eaves is often the only indication of a timber-framed origin for an otherwise stone building. At 35–36 St. Peter's Street the front wall was, exceptionally, built internally thereby reducing floor space inside the house. In 1747 John Burton leased a house at the N.E. corner of Castle Street with a covenant to spend £50 on repairs, including building the 'outward walls' in stone (Hall Books 3, 162).

Cellars

Many houses in Stamford have cellars, but as most are devoid of architectural detail it is almost impossible to know their date. Several medieval structures may have escaped recognition because of the lack of datable features. Nos. 1–2 Castle Street (153) illustrates the problem, for none of its visible detail is easily dated, but is almost certainly of late medieval date.

Documentary references show that cellars were being built by the 13th century; the earliest one recorded was 12½ ft. by 15 ft. (PRO, E 315/44, p. 39). The Hundred Rolls record no less than five new cellars constructed in the third quarter of the 13th century. Richard of Wardale built a cellar in St. Mary's parish about 1267, approached by steps occupying an area 8 ft. wide and 4 ft. long in the street. John Plouman, in the same parish, had his cellar steps next to his house door. About 1257 Gilbert of Cestreton, a wool merchant, built three cellars with external steps opposite the W. gable of All Saints' Church; the building may have been a terrace forming part of a speculative enterprise (Rot. Hund. 351b, 352a).

Three vaulted undercrofts of the 13th century survive, one of which (1 St. Mary's Place (340)) is only a fragment. A fourth example is known from excavations (16). That at 24 High Street St. Martins (214) is a simple rectangular vaulted structure without any original openings. At 13 St. Mary's Hill (338) the undercroft is two bays wide and was originally at least three bays long. The entry from the street is preserved almost intact, and suggests that the undercroft was used as a shop. The later undercroft at 23 High Street (183) may have served a similar function (Plates 58–60).

The 15th-century vaulted undercroft at 4 St. Mary's Place (342), also entered from the street, may have been below a guildhall. A former undercroft at the Bull Inn (352) seen by Stukeley in 1746 had eight vaulting ribs meeting at a central boss shield (3 dolphins salient) and had two blocked windows on the S., street, front (Surtees Soc. 76 (1883), p. 339). The undercroft below 69 High Street St. Martins (238) could not be examined; the building above is of c. 1500.

Cellars covered by beam-and-joist floors are difficult to date, but were common in the 18th and 19th centuries. The better-class cellars, however, have elliptical vaults. Their side walls are commonly coursed rubble, but the vault itself is of well-cut ashlar. They occur at the very beginning of the 18th century (e.g. the cellars below the Theatre (60) and 18–19 High Street (180)) and continue until well into the early 19th century. That at 46 High Street St. Martins is of brick and dates from c. 1830 (228).