Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'St John Street: Introduction; west side', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, (London, 2008) pp. 203-221. British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp203-221 [accessed 26 April 2024]

In this section

CHAPTER VIII: St John Street

An ancient route, St John Street was described in 1170 as the street 'which goeth from the bar of Smithfield towards Yseldon [Islington]'. This is the earliest known documentary reference to the street, which later became known simply as 'ClerkenwellStreete'. Its present name, taken from the adjacent priory of St John, established by the Knights Hospitallers in the twelfth century, has been in use certainly since the fifteenth century. Historically, however, it applied only to the lower half of the street, the upper half being known variously as the Chester road or Islington Road, and later as St John Street Road until 1905, when it was redesignated part of St John Street. Until 1866, lower St John Street was itself divided into two separately numbered parts: St John Street, Smithfield (in the parish of St Sepulchre Without), and St John Street, Clerkenwell.

There remains to this day a difference in character between the two halves. In the southern, former warehouses and factories predominate, the outcome of centuries of commercial and industrial activity on a mostly fragmented pattern of landholding. By contrast the former St John Street Road has been largely residential since it was built up in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The frontages here, divided among only a handful of landed estates, were mostly filled with more or less uniform terraces. Some of these houses survive, while others were replaced by council flats in the 1950s and 60s.

For centuries St John Street was at the edge of London, Smithfield Bars at the lower end marking the entrance to the City, and the open fields beside its northern reaches the passage from town to country. It was the route for drovers and traders coming from the north through Islington to the markets in and around Smithfield—the livestock market itself, held from the tenth century; Bartholomew Fair, held on the same ground, which began as a cloth fair in 1123 and continued until the closure of the livestock market in 1855; and the cattle market at Cow Cross, which flourished in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. In addition, from the late seventeenth century until the early nineteenth, a skin market was held just off St John Street, on the site of the present-day Brunswick Estate, near Northampton Square.

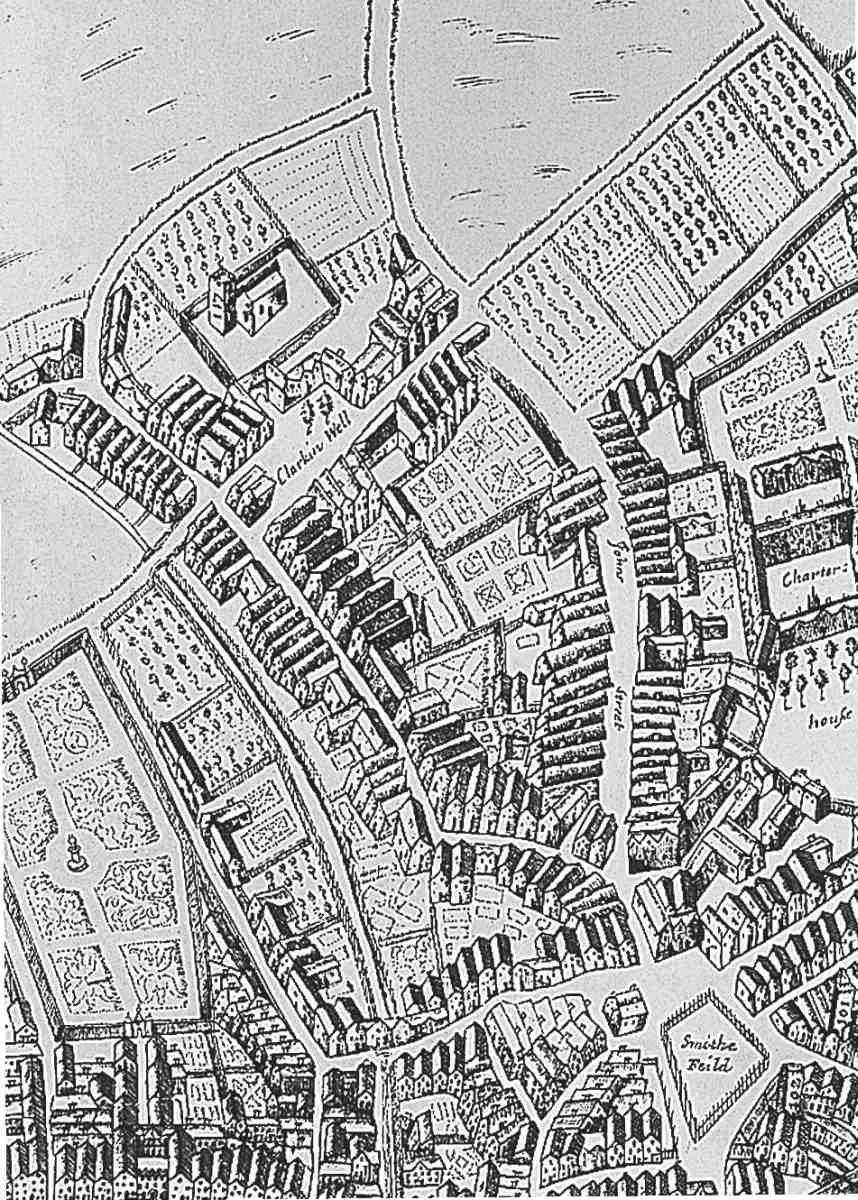

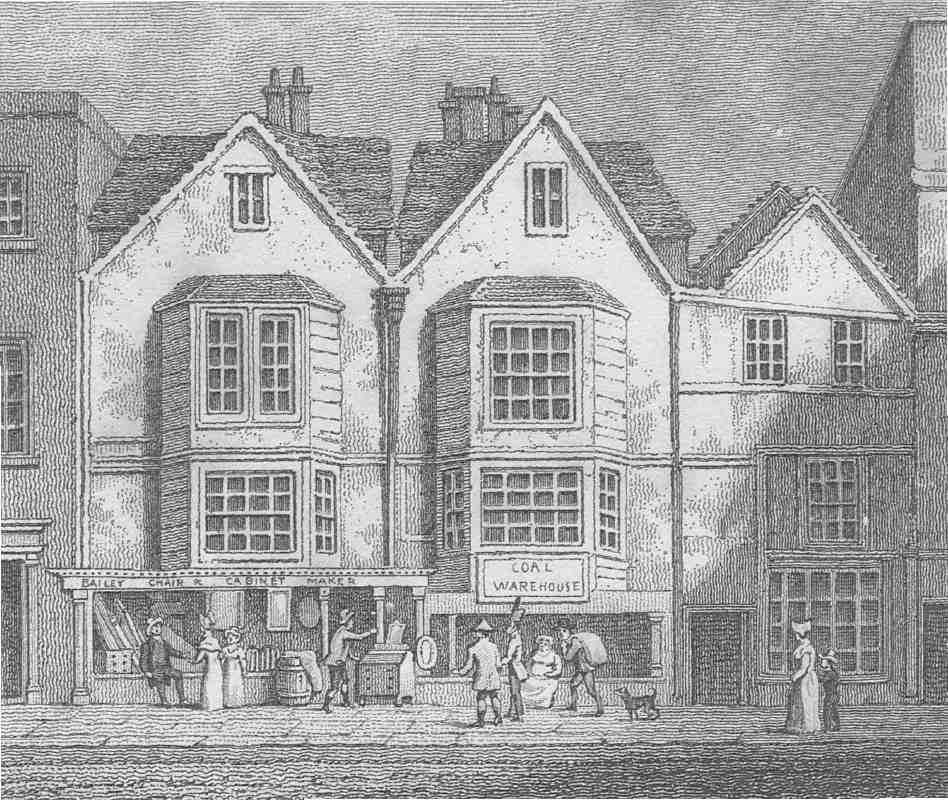

A royal patent of 1380 authorized customs to be taken from those bringing animals and goods to London, to help fund repairs to the roadway from Smithfield to Islington. The lower part of the street at this time was probably little built up, though there had been dwellings and gardens just north of Smithfield since c. 1200 or earlier. (fn. 1) In 1544 a statute enabled residents who improved the roadway in front of their houses to deduct the cost from their rent, suggesting that the street was now more fully lined with buildings. (fn. 2) Stow in 1599 described St John Street as 'replete with buildings up to Clarken Well' (i.e., to modern-day Aylesbury Street), a picture confirmed by maps and engravings, which show lower St John Street with rows of narrow-fronted buildings similar to those of the pre-Fire City (Ill. 256). Three houses of this sort survived on the site of Nos 69–73 until about 1814 (Ill. 258). There were one or two larger houses or mansions among these rows, and a multitude of small dwellings in courts and yards behind.

256. St John Street and vicinity from Faithorne & Newcourt's map (1658)

By the early seventeenth century St John Street had become an important staging post for carriers and coaches. Hicks' Hall, the Middlesex sessions house, which stood on an island in the street at the bottom of St John's Lane, became one of the capital's datum points, and even after its demolition in the 1780s, distances to northern destinations continued to be measured from the site. Carriers and salespeople lodged at inns along St John Street, conducted their business there, stored goods in the yards and outbuildings, stabled horses and parked wagons. The Warwickshire and Leicester carriers used the Castle, near Smithfield Bars; the Nottingham and Daventry carriers the Cross Keys, opposite Hicks' Hall; those from Bedford and Buckinghamshire the Windmill. (fn. 3) In Moll Flanders, the heroine carries out a confidence trick on a maidservant trying to obtain seats for the Barnet coach at the gate of the Three Cups inn, on the east side of the street.

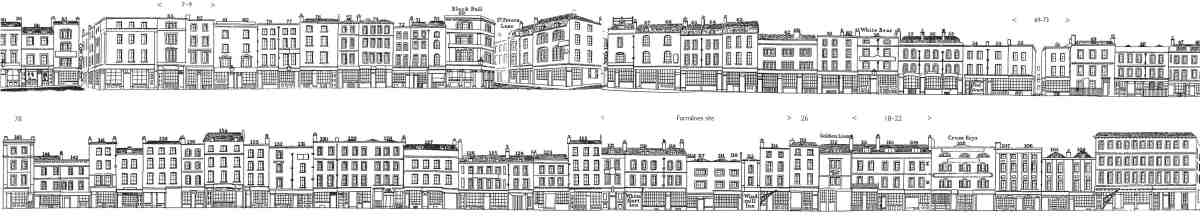

257. Houses and shops at the lower end of St John Street, c. 1838–40, west side above, east side below (from Tallis's London Street Views). Some modern street numbers have been added for reference

258. Sixteenth-century houses on the site of Nos 69–73 St John Street, recorded shortly before demolition, c. 1814

The earliest known inns and alehouses in St John Street belonged to the nearby religious houses, providing income as well as extra accommodation for visitors. These included: the Bell on the Hoop, the Lamb, the Mill, and the Rose (all from at least c. 1200); the Key (c. 1336), the White Harte (1394); the George, the Ball, the White Lion (1470s–90s); the Castle, the Windmill and the White Willow (1530s and 40s). (fn. 4) After the Dissolution they continued in private ownership, reaching the height of their trade in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Ogilby & Morgan's map of 1676 indicates seven on the eastern side of the street between Smithfield Bars and (Great) Sutton Street; Rocque's (1747) shows nine. The depth of the plots on the east side allowed large yards with stabling, coach-houses, brewhouses and barns.

A number of these inns closed in the mid- and later eighteenth century, probably in consequence of the opening of the New Road, which diverted droving traffic away from Oxford Street and Holborn, taking it north of the City and down the Islington Road and St John Street from the Angel. The increased pressure on St John Street must have made conditions intolerable, and it was partly for this reason that a new site was found when Hicks' Hall came to be rebuilt in the late 1770s, for neither Justices nor visitors could approach the building on market days 'without imminent danger of personal mischief from the Horned Cattle'. (fn. 5) A few of the old inns have successors in pubs of Victorian and later date, and alleys such as Hat and Mitre Court remain to mark the site of former coaching-inn yards.

Tallis's guide of 1838–40 shows the lower end of St John Street lined by shops and inns, mostly appearing to date from the eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries (Ill. 257). It had an essentially high-street character, geared to the presence of many travellers and passers-by, with coffee-houses and eating-houses, and a wide range of shops and trades, but very few of the clock- and watchmakers, jewellers or printers particularly associated with other parts of Clerkenwell.

The removal of the livestock market to the new London Metropolitan Cattle Market at Copenhagen Fields in 1855 brought to an end an ancient but anachronistic tradition. St John Street was freed from droving, and its associated hazards and barbarity. But the connection between Smithfield and the meat trade continued, with the Corporation of London's decision to move the London meat mart from the long inadequate Newgate Market (on the site of Paternoster Square) to the old saleground. The opening in 1868 of the new Smithfield Market for meat and poultry led to the south end of St John Street being almost entirely taken over by butchers and associated traders: wholesale butchers and provision merchants, tripe-dressers, sausage and sausage-skin makers, baconcurers, even such specialists as butchers' outfitters. Many of the new buildings in the area were purpose-built for these concerns.

Land-ownership and estate development

By the time of the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII nearly all the land fronting St John Street belonged to one or other of the several local religious houses. This included most of the small built-up plots at the southern end, where the landownership pattern had already become irregular and bitty. Much of this southern frontage, particularly on the east side, was in the possession of the priory and hospital of St Bartholomew, in Smithfield, including a number of inns, and the Knights Hospitaller owned properties here, outside the precincts of St John's priory, on both sides of the road. St Mary's nunnery, too, had some property in St John Street near Smithfield Bars. On the east side of the street, opposite the priory church, a longish strip of frontage formed part of the estate belonging to the Charterhouse, outside the monastic precincts, but as yet unbuilt-on, or largely so.

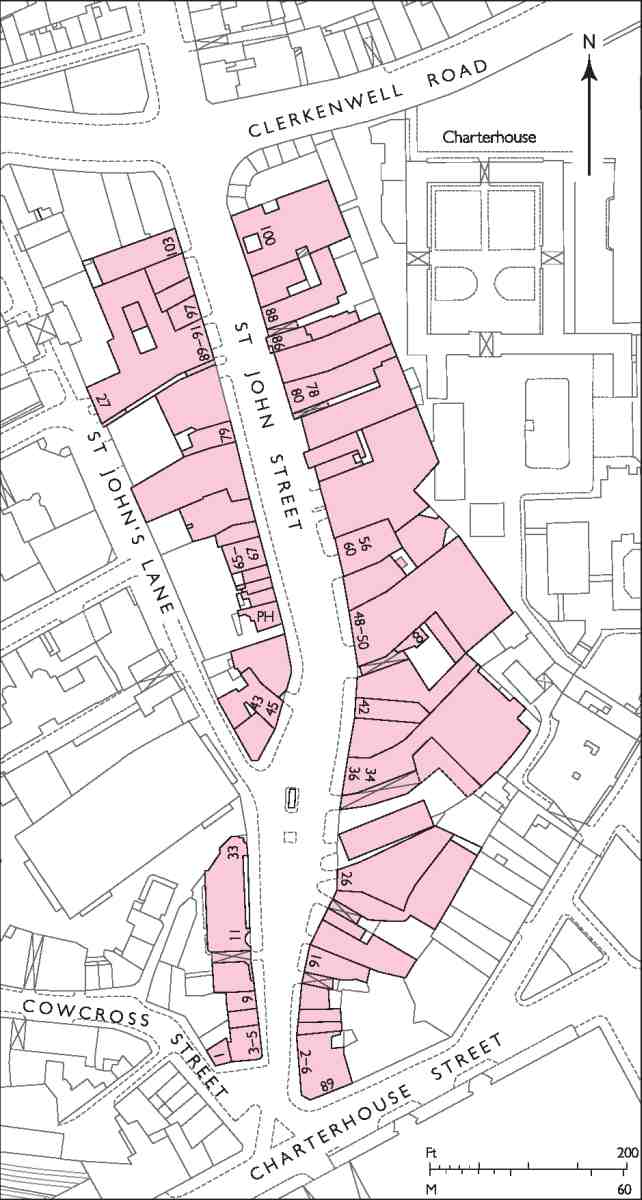

Further north, almost to the Angel, the frontages to St John Street on both sides remained undeveloped until after the Dissolution, and the landownership pattern until recent times was essentially that established by Crown disposals of former monastic land then and later in the sixteenth century (Ill. 4).

A considerable amount of building had taken place by the end of the seventeenth century on the Charterhouse estate, and on the Seckford Charity estate on the west side of the road north of Aylesbury Street. On the Charterhouse estate this consisted largely of small houses, shops and workshops, with some larger industrial buildings. The Seckford estate was similar in character, with several courts of houses created from inn yards off St John Street. Streets of houses had also been laid out immediately north of the Charterhouse estate, on Woods Close, belonging to the Earls of Northampton.

Other than some old development at the north end of St John Street, at the junction with Goswell Road, there were few buildings on the northern half of the street until the 1760s and 70s, when further development took place in Wood's Close, in and around Taylor's Row, and on the Brewers' Company estate immediately to the north. Barring a few gaps, the eastern side of the street was fully built up by the 1790s. The open fields on the west side, belonging to the Skinners' Company, the New River Company, and the Lloyd Baker family, were built over from the 1820s, a process largely complete within twenty years.

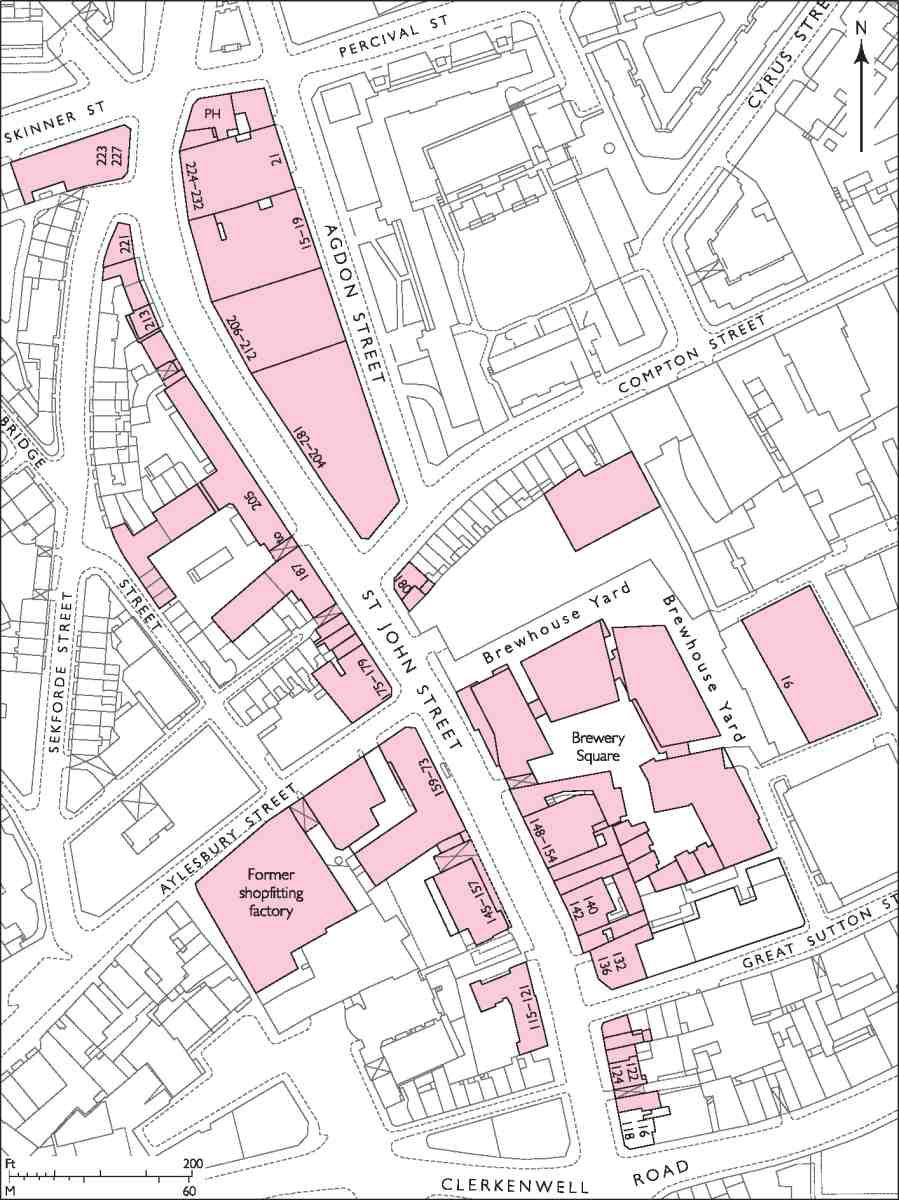

259. St John Street, from Smithfield to Clerkenwell Road

Hicks' Hall (demolished)

From at least the 1540s the Middlesex magistrates sat in the Castle inn, on the west side of St John Street near Smithfield Bars, or the Windmill, further north on the east side. In the 1570s Queen Elizabeth granted a lease of waste ground in the street for building a sessions house to Christopher Saxton, the surveyor and cartographer whose patron Thomas Seckford lived near St John Street and owned several acres there (see Chapter II). (fn. 6) But nothing further seems to have been done until 1609, when James I was successfully petitioned for a site in the roadway where it broadened out at the bottom of St John's Lane, opposite the Windmill inn.

Intended for both a sessions house and—to relieve overcrowding at Newgate—a small prison, the site measured 120ft by 32ft, allowing 20ft on either side for traffic to pass. (fn. 7) The sessions house was erected here in 1612 at the personal expense of one of the justices, Sir Baptist Hicks, Knight (later Viscount Campden), silk mercer and financier to the King, in recognition of whose largess the name Hicks' Hall (otherwise Hicks or Hicks's Hall) was adopted at the first meeting held there, in January 1613. (fn. 8) However, the site proved too small for the prison (another site for which was obtained, near Clerkenwell Close), though a 'round-house' or lock-up was built, presumably the small wing at the north-west corner of the building shown on Ogilby & Morgan's map (1676). (fn. 9)

The external appearance of Hicks' Hall is uncertain. The only detailed views (showing the principal, south elevation) were made several decades after the building had been demolished and, if the detail they show is authentic, must derive from a now-lost original. The quaintly pretty building they depict (Ill. 261) is hard to reconcile with the 'shapeless brick lump, containing a great warehouse in the centre for the Court, and houses for the officers all round, joined on to it', recalled by a writer in 1827. (fn. 10) Two of these views show Hicks' Hall superimposed on the early Victorian backdrop of St John Street; the third, published in the Illustrated London News in 1863 and subsequently in Pinks's Clerkenwell, was said to be from 'a print of some rarity in a private collection'. (fn. 11) A possible explanation is that they are based on no more than the thumbnail elevation on William Morgan's map of 1682, which confirms the small gable and large upper-floor window. None of the known elevational views shows the three projections on the south front indicated on Ogilby & Morgan's map of 1676.

Hicks' Hall is said to have been mostly of brick, with stone dressings, though in the mid-eighteenth century the brickwork seems to have been at least partly rendered over. (fn. 12) The court-room, 28ft by 16ft, was on the ground floor. (fn. 13) Above were Great and Lesser dining-rooms, each decorated with a portrait of Hicks. There were also separate rooms for the grand jury and the Clerk of the Peace, and a kitchen, closets, wash-house, garret store-room and cellar. (fn. 14) Stocks were set up at the back of the building, and in 1622 these were enclosed by a cage to protect them from violence offered by 'lewd persons'. (fn. 15) In 1722 alterations and repairs to the structure included the building of a new bail dock (for keeping prisoners during trials) in the courtyard. In 1773 a fire-engine house and a watch-house were also erected in the yard. (fn. 16)

The story of a room in Hicks' Hall set aside for public dissections, macabrely adorned with the skeletons of notorious criminals in the manner depicted in Hogarth's The Reward of Cruelty, was first published in 1855 and appears to be without foundation. (fn. 17)

Defoe's Moll Flanders refers to herself as 'well-known at Hick's Hall, the Old Bailey, and such places'. In real life the court was connected with three nationally important cases in the late seventeenth century: in 1660 the trial of twenty-nine of the Regicides began at Hicks' Hall (pro ceedings then continuing at the Old Bailey Sessions House), and in 1679 Titus Oates was among those who gave evidence here concerning the Meal Tub Plot. William, Lord Russell, was condemned to death in Hicks' Hall following his trial at the Old Bailey, in 1683, for his part in the Rye House Plot.

260. St John Street, from Clerkenwell Road to Skinner and Percival Streets

By the 1770s St John Street had become too busy and noisy for court business, itself steadily increasing, to be conducted satisfactorily in Hicks' Hall. The building was in any case cramped and decrepit, with bulging walls, decayed brick and rotten woodwork. So poor was the accommodation that it was impossible to get anyone of respectable standing to serve on a grand jury; there was no room for the reception of witnesses, those attending having to stand outside until called for. (fn. 18)

As early as 1770 the magistrates had in mind the rebuilding of Hicks' Hall, for which plans were drawn up by the county architect, Thomas Rogers. St Sepulchre's Paving Commissioners agreed to make available extra ground, increasing the length of the site from north to south by twenty feet, and evidently taking in a few extra feet from the street to give more width as well. (fn. 19) A plan and section thought to be part of a scheme by Rogers show an oval building, with two square staircase wings and covered by a steep roof, comprising a single chamber with tiered galleries, the lower two fitted with benches. The apparently detached structure, measuring about 35ft by 45ft, would have covered only a third of the site. The remainder of the ground would presumably have been taken up with another building or buildings to house the necessary ancillary rooms. This may have been the scheme outlined by Rogers for the old site in 1777 in his testimony to the House of Commons committee on the justices' petition for rebuilding Hicks' Hall. He described the proposed court-room then as a 'circle', 36ft in diameter, and lit by a dome, to avoid having windows opening on to the street, a particular source of annoyance at Hicks' Hall. (fn. 20)

261. Hicks' Hall: a Victorian 'retrospective' view by T. H. Shepherd

Rogers' solution was never put to the test, however, as the case for another site proved compelling. The new sessions house in Clerkenwell Green was completed in 1782, by the end of which year Hicks' Hall had been demolished. Some furniture, and a carved oak chimneypiece, one of the original fittings, were removed to the new building. This chimneypiece (Ill. 259), incorporating the arms of James I and Sir Baptist Hicks, survives today in the Inner London Crown Court in Newington Causeway, where it was moved after the closure of the Clerkenwell Green Sessions House. (fn. 21)

Plans to mark the site of Hicks' Hall with a stone column, to perpetuate its role as a reckoning-point for distances from London, were eventually abandoned. (fn. 22) In the late nineteenth century a public convenience was erected on the spot; a traffic island now occupies its place.

262. Chimneypiece from Hicks' Hall, reinstalled at the Middlesex Sessions' House, Clerkenwell Green, photographed in 1914

Present buildings

More than any other street in Clerkenwell, St John Street bears witness to continued piecemeal rebuilding over several centuries, partly at least because of its sheer length and the many small freeholds. The mostly small size of the businesses located here, the area's sharp industrial decline in the second half of the twentieth century, and its undesirability (whether to planners or developers) for offices, are the other main factors. The consequence is a street with a wide range in both style and scale of building, its earliest houses dating from the early eighteenth century. These are modest though far from mean buildings, domestic in character and contrasting appealingly with the taller, overtly commercial and often quite ornamental edifices of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: taller, but not necessarily wider, as the pattern of ownership has helped to perpetuate some of the narrow plots first built up in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, if not earlier (see Ill. 296). St John Street's longstanding role as a coach road, too, has left a legacy of many public houses, though most of these have long passed out of use as licensed premises. From Smithfield to the Angel, St John Street is enlivened by a succession of large pubs, almost all of them rebuildings carried out in the last quarter of the nineteenth century (Ills 263–270). Purpose-built flats and model dwellings hardly figure in the southern half of the road at all, the London County Council's Mallory Buildings being the only instance, the product of a fairly minor slum-clearance programme. This absence is again a consequence of the gradual, evolutionary character of redevelopment here.

All this makes for a radically different streetscape from that of the Victorian arteries such as Farringdon Road, where the broad new building plots encouraged the erection of factories, warehouses and 'industrial dwellings' on a comparatively monumental scale. Only a few St John Street buildings are in any way comparable. One is the former Nicholsons' Distillery (Ills 287, 288). Another, long demolished, was the London Printing & Publishing Co.'s works (Ills 292, 293).

On the whole, the twentieth century saw the replacement of Georgian and Victorian buildings with an increasingly dull parade of utilitarian structures, including a number in the conventional Modernist manner built after the Second World War for firms in the meat trade. These have nearly all been subject to cosmetic or other alteration in the course of conversion to apartments in recent years. In contrast, the former showrooms of the shopfitters E. Pollard & Co. (1920s) stand out as a stylish building which might belong in Farringdon Road, Clerkenwell Road, or Rosebery Avenue.

The following gazetteer of buildings is arranged in two sections: the historic St John Street, running from Smithfield up to the junction with Skinner and Percival Streets, and the former St John Street Road. Buildings on the east side, from Rawstorne Street northward, are dealt with individually in Chapter XII.

Smithfield to Skinner and Percival Streets: west side

Smithfield to St John's Lane

At the bottom of the island block east of Cowcross Street and Peter's Lane two buildings numbered in St John Street face south over the site of Cow Cross, towards the Grand Avenue of Smithfield Market (Ill. 274). No. 1, on the Cowcross Street corner, is in the 'Venetian' style, with a moulded brick cornice and a white-brick panel high up carrying the address. A wall-mounted crane and alterations to the windows give the building an industrial character it may not originally have had. It appears to have been built in the mid-1880s for Frederick Goodspeed, a grocer who had acquired, and briefly ran, an old coffeehouse on the site. Rebuilding, whether as a coffee palace or a warehouse, was financed through loans from William Robinson & Son, solicitors in Charterhouse Square. Though Goodspeed was describing himself as a builder about 1882, it is unlikely he actually built No. 1, tenders for which were obtained in 1883. The architect was S. C. Aubrey. (fn. 23)

Nos 3–5 adjoining were built in 1897 for William Harris the 'Sausage King', sausage manufacturer and proprietor of a well-known restaurant chain specializing in sausage and mash. He had been trading from premises at No. 3 since the 1870s. The builders were Hall, Bedall & Co. and the architect was Francis John Hames, who as a young man had designed Leicester Town Hall (1873–6). Hames practised under the name Hames & Darling, but it is not clear who his partner was or whether he was active at this time: he was possibly the Canadian architect Frank Darling, who briefly worked in England. (fn. 24) The building, faced in brick with stone dressings, shows Arts-and-Crafts and Art Nouveau influence; the south front rises to an ornate gable decorated in relief with a wild boar, Harris's name and the date (Ills 274, 275).

The new premises, comprising stores, shop, offices and living accommodation, were erected on a fifty-year building lease from St Bartholomew's Hospital, the freeholder. Harris also leased the two old houses adjoining, Nos 7–9, where he added shop-fronts, ornamented with a poppy motif, matching those on Nos 3–5. Apart from this change, and the addition of a mansard storey, the fronts seem to have been altered little since they were sketched for Tallis's street views about 1839 (Ill. 257). (fn. 25)

William 'No. 1' Harris, as he styled himself, lived over the shop at Nos 3–5 with his family (including sons William 'No. 2' and William 'No. 3'), and his firm, William Harris & Son, remained here until the late 1950s or early 60s. In the 1980s the upper floors of Nos 7–9 were fitted up as a private sex cinema, which was set on fire in 1994, killing eleven people. The mansard was added during restoration the following year. (fn. 26)

263. No. 16, former Cross Keys (1886–7), in 2006

264. No. 57, White Bear (1898–9), in 2006

265. No. 99, former Horns (1887), in 2006

266. No. 240, former George and Dragon (1889–90), now The Peasant, in 2004

Public Houses, St John Street

267. No. 303, Coach and Horses (1898). Demolished

268. No. 370, former New Clown (c. 1900), in 2004

269. No. 418, Old Red Lion (1898–1900), in 2007

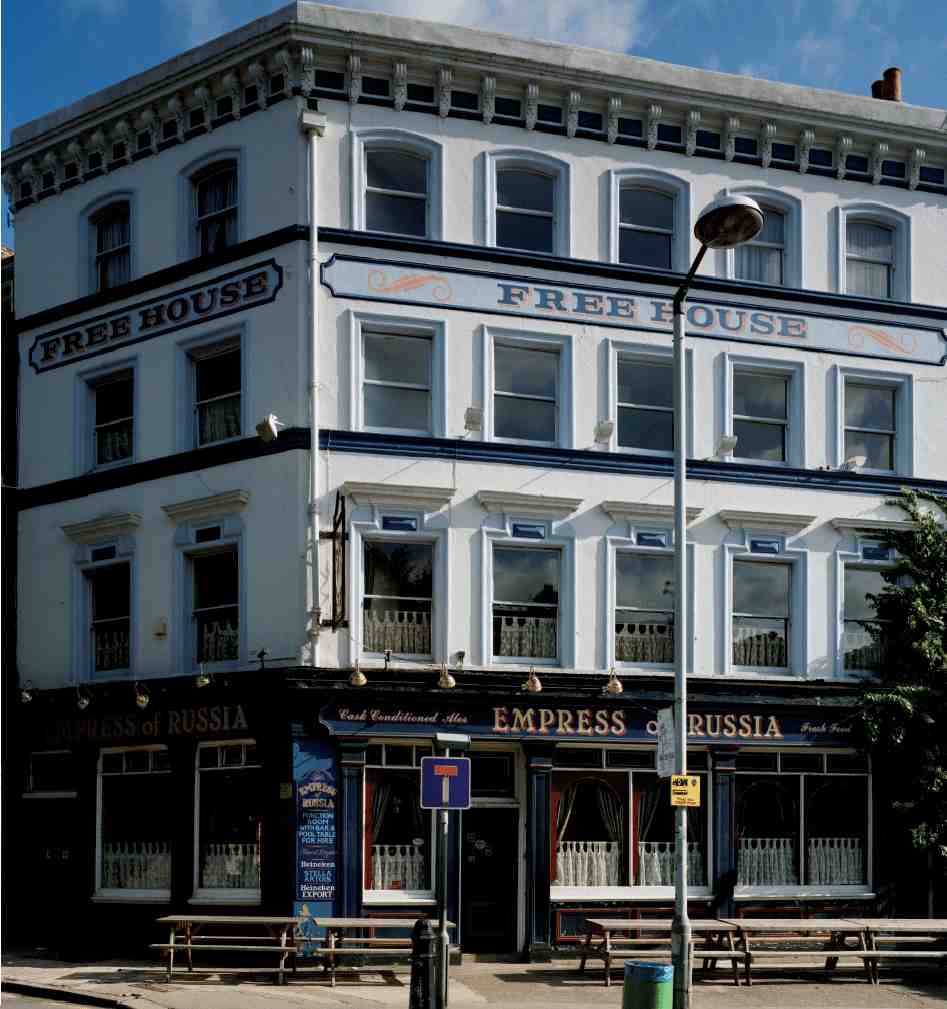

270. No. 360, Empress of Russia, in 1998

Recent Buildings in St John Street

271. Flats at Brewhouse Yard, part of the former Cannon Brewery site, in 2004. Hamilton Associates, architects, 2004

272 (right). City University School of Social Sciences, in 2006. Stanton Williams, architects, 2004

273. Mews houses, Brewhouse Yard, in 2004. Hamilton Associates, architects, 2004

Nos 11–33 were built in the late 1980s, together with No. 22 Peter's Lane, on the site of long-demolished cold stores. The southernmost part of the development was planned for light-industrial purposes, the remainder as offices. Designed by Roger Zogolovitch of CZWG, it is stylistically an insipid affair, apparently the consequence of watering down the original rather Egyptianizing design. (fn. 27) Nos 11–33 are now occupied by the marketing consultancy the Henley Centre.

The cold stores were built in 1895–6, for the London and India Docks Joint Committee, in response to pressure from the frozen-meat trade for extra storage close to Smithfield Market. Known as the West Smithfield Cold Air Stores, the building appears to have been designed by the committee's engineer, F. H. Donaldson (though applications to the London County Council regarding its construction were made by a Mr J. Webster, possibly the architect James Webster, then of Mecklenburgh Square). It was built by Mowlems, with brine-circulation refrigerating plant manufactured by J. & E. Hall Ltd. The building included a row of shop units along St John Street, let to firms in the meat and provisions trade (Ill. 276). (fn. 28)

Though the cold stores remained in use until the 1960s, they had proved inadequate after only a few years and in 1913–14 cold stores on a larger scale were built by the Port of London Authority (successor to the docks committee), near by in Charterhouse Street. The West Smithfield Cold Air Stores were demolished in 1969 or soon after, and the site was used as a car park until its redevelopment.

St John's Lane to Clerkenwell Road

With the exception of a pair of early nineteenth-century houses at Nos 69–73, the buildings between St John's Lane and Clerkenwell Road are of late Victorian or modern date, most of them built speculatively as commercial premises. The present Nos 65–67 replaced buildings of 1895 in the late 1980s, as part of the Watchmaker Court development in St John's Lane. (fn. 29)

Besides these commercial buildings are two public houses from the same period: the White Bear at No. 57 (Ill. 264), rebuilt in 1898–9 by the City of London Brewery Co., along with the adjoining house No. 59; and the former Horns of 1887 at No. 99, by Alexander & Gibson, architects (Ill. 265). The new Horns was part of extensive redevelopment in this part of the street and St John's Lane, much of it—including Nos 89 and 91—for the provision merchants Lovell & Christmas (see page 159). (fn. 30) No. 55 (Tompion House) is an office development of the mid-1990s.

274. Looking north-west from the Grand Avenue, Smithfield Market, in 2004. Left to right: Cowcross Street; Nos 1–9 St John Street; Nos 2–6 St John Street

275. Nos 3–5 St John Street in 2004. Hames & Darling, architects, 1897

276. West Smithfield Cold Air Stores under construction in 1895. Demolished

277. Nos 69–73 St John Street in 2004

Nos 69–73 consist essentially of two houses built in 1817–18, originally separated by the entry to a large yard, where warehousing was later built (Ill. 277). They replaced old houses thought to have been part of the mansion of Sir Thomas Forster on St John's Lane (Ill. 258). The northern house was first leased by John Newton, cork manufacturer, who later took over the entire premises, and whose firm remained here until the First World War. (fn. 31) Tallis shows the houses with shop-windows across the fronts, access presumably being by side doors (Ill. 257).

No. 69 appears to retain its original façade, but the other house has been refronted; this may have been done in 1896 when it was extended over the alley and the two houses thrown into one, together with the cork-warehouses at the rear, which had been partly rebuilt following a fire in 1882. (fn. 32) The treatment of the ground floor at No. 69, with arched openings and Ionic pilasters, executed in stucco, is the remnant of a remodelling of the whole ground-floor front of Newton's premises, probably carried out in the mid-nineteenth century. The present shopfront at No. 73 dates from 1884, though it has been altered in recent years. (fn. 33)

No. 105, which incorporates No. 25 Clerkenwell Road, is a tall red-brick warehouse, probably built in the 1890s.

278. St John Street, west side, c. 1900, looking south from Aylesbury Street, shortly before clearance for road-widening

Clerkenwell Road to Aylesbury Street

This part of the street acquired its present form in 1900–6, when the London County Council carried out extensive clearance, widening the roadway by thirty feet, obliterating the courts in the vicinity of Aylesbury Street and St John's Church, and curtailing the churchyard (Ill. 278). Among the buildings demolished were the premises of Pfeil, Stedall & Son, machine-tool dealers, and so part of the clearance land was allocated to them for a new warehouse and offices. (fn. 34) Adjoining this the council put up Mallory Buildings, to replace some of the lost housing. The last of the clearance land, having failed to attract a developer, was made available to the London Vacant Land Cultivation Society led by Joseph Fels, the Philadelphian soap magnate and philanthropist, for 'vacant-lot' farming by the unemployed. (fn. 35) The site was subsequently built over as part of Pollards' shopfitting works.

Nos 145–157. In 1971–2 the premises built for Pfeil, Stedall & Son were replaced with the present curtainwalled building, designed as a showroom and offices. Of 'a particularly sophisticated character' for the area, it was intended to set the standard for further local redevelopment. The architects were Michael Lyell Associates. (fn. 36)

279. Mallory Buildings and Nos 115–121 St John Street in 1906. London County Council Architect's Department, 1904–6

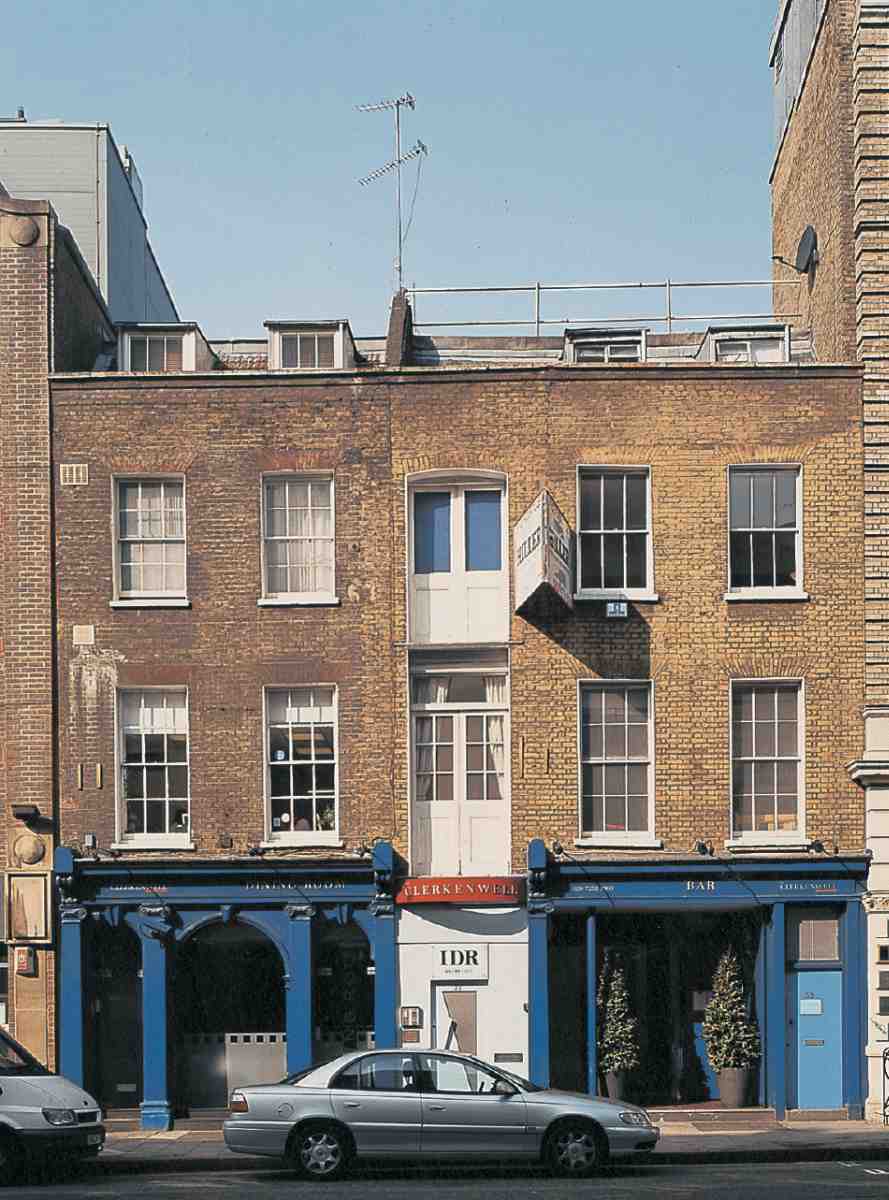

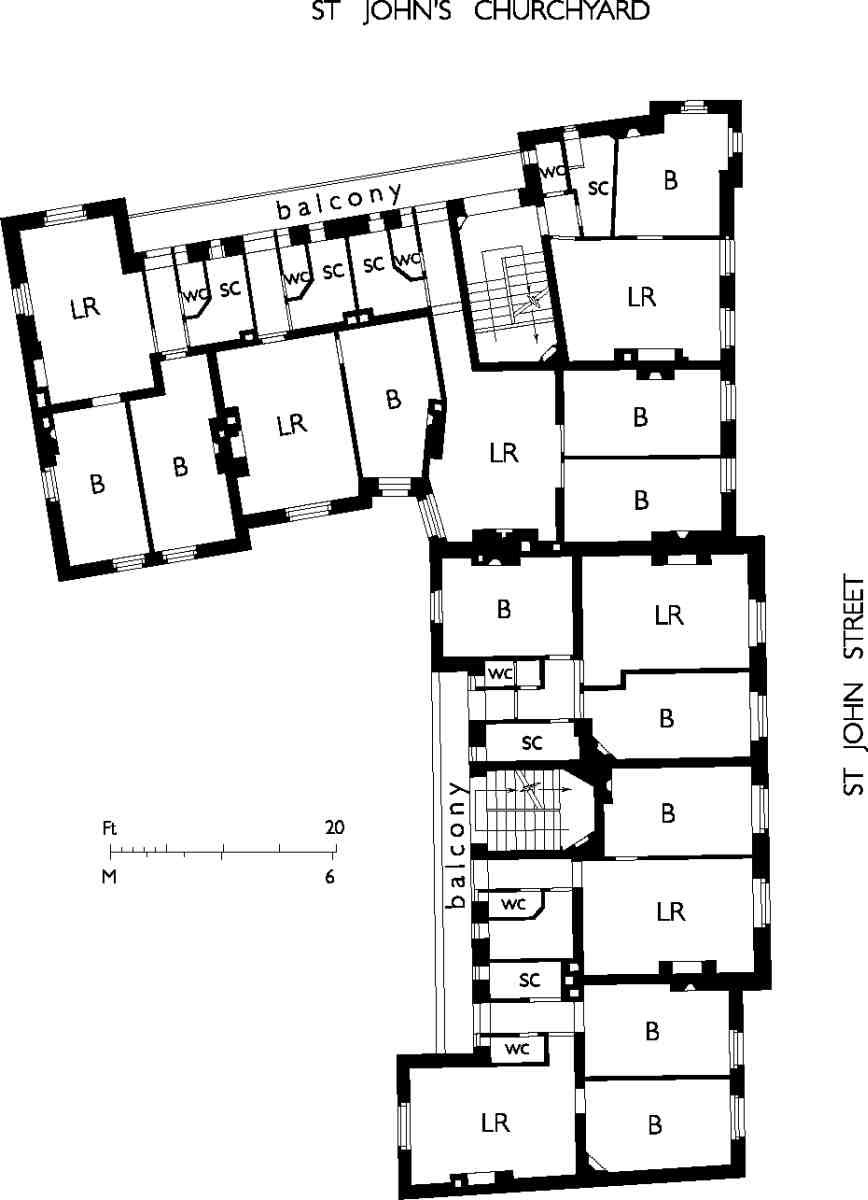

Mallory Buildings and Nos 115–121. This block of tenements and shops belongs to the select group of publichousing schemes designed by the LCC Architect's Department in the 1890s and early 1900s in an Arts-and Crafts or 'English Domestic' idiom, generally now regarded more highly than its later neo-Georgian work (Ills 279, 280). Planned in 1902, it was built in 1904–6; the contractor was T. G. Sharpington. Mallory Buildings stands on part of the site of the medieval priory of St John, relics of which were discovered during the excavation for the foundations. The name commemorates Robert Mallory, one of the former priors. (fn. 37)

280. Mallory Buildings, first-floor plan as built

Pollards' shopfitting works. Nos 159–173 and the buildings adjoining at the rear, in Aylesbury Street and Jerusalem Passage, together made up the Clerkenwell factory of E. Pollard & Co. Ltd, renowned manufacturers of shopfronts, display fittings and other contract joinery and metalwork (Ills 281–284). The buildings date from three main phases and comprise the main workshops on the corner of Jerusalem Passage and Aylesbury Street (1912–13 and 1919); the L-shaped range at Nos 159–173 (1920s); and the minor buildings between these two blocks, fronting Aylesbury Street (1930s).

Pollards, founded in 1895 by Edward Pollard in Kingsland Road, Shoreditch, moved in 1906 to No. 29 Clerkenwell Road, which remained the firm's 'City' showrooms after the building of the new factory. About 1919 a second factory, making jewellers' sundries, was built in Highbury, and during the 1920s and 30s Pollards continued to expand, opening West End showrooms at No. 299 Oxford Street, and establishing branches in Bristol, Manchester, Glasgow and Dublin. By the mid-1920s the firm could claim '12 acres of workshops'. (fn. 38) In 1930 it merged with Samuel Haskins & Bros. Ltd, shopfitters and roller-shutter manufacturers, opening offices in Paris and Brussels; Pollards' Continental business, however, was closed down a few years later. (fn. 39)

Pollards held the English patents for the American invention 'invisible glass', used in shopfronts. This employs steeply curved concave glass to deflect light towards matt black 'baffles' so that no reflections show in the window. Pollards installed invisible-glass windows in several important London stores, including Simpsons of Piccadilly (now Waterstones), where they remain intact. They also built up a business in the manufacture of architectural metalwork, particularly bronze doors. Other work undertaken included fitting out liners for John Brown's shipyard, Clydebank. (fn. 40)

In 1967 the Pollard Group relocated to Basingstoke and the business continues today as Pollards Fyrespan, now in Enfield. The former Clerkenwell works are now used as offices and small-business workshops.

281. Nos 159–173 St John Street in 2004. Malcolm Waverley Matts, architect, 1925–7, for E. Pollard & Co. Ltd

282. Nos 159–173 under construction in 1925; behind are Pollards' factory buildings of 1913–20, by J. B. Gridley, architect

283. Pollards, sign-writing department, 1920s

284. Pollards, metal-finishing department, 1920s

Pollards' Shopfitting works

Under its leasing agreement with Pollards, the LCC retained for a few years a temporary iron building on the southern part of the St John Street frontage, accommodating clerical staff in the Stores Department, which had a large depot in the former London School Board's stores, near by in Clerkenwell Close. (fn. 41) Another part of the ground was still occupied by a row of houses in Aylesbury Street (Nos 2–7), not finally cleared and demolished until the 1930s. Building therefore began at the back of the site, alongside Jerusalem Passage, and until the St John Street extension was built the firm's address was given as 'St John's Square', though it had no frontage to the square itself.

285. Nos 223–227 St John Street, 1930s logo of Ingersoll Watch Company Ltd, in 2006

The buildings of 1912–13 were designed by the architect J. B. Gridley with constructional steelwork designed and supplied by Archibald D. Dawnay & Sons Ltd (Ill. 282). (fn. 42) They were used in the latter stages of the First World War for aircraft production. The second and third floors were not added until 1919–20, when temporary rooftop workshops for War Office contracts (including the manufacture of framed tents and ammunition cases), were taken down. They are very plain buildings, steel-framed with reinforced-concrete floors, faced in stocks with banding in blue engineering brick on the ground floor.

Pollards did not begin its building on the St John Street frontage until the mid-1920s. But already in 1914 the firm's letter-head bore an illustration of 'the largest shopfitting factory in Great Britain', showing the whole frontage there occupied by an imposing factory, matching Gridley's buildings in style, with a flying pennant over the entrance and a sky-sign along the parapet proclaiming Pollards 'the' shopfitters.

For the St John Street building a new architect was employed, Malcolm Waverley Matts, who produced an up-to-date façade, not especially ornamental but sleekly clad in cream faience above a plinth of black granite (Ill. 281). Black granite was also used to frame the bronze entrance doors. Construction was carried out in 1925–7, by John Greenwood & Sons, with steelwork by DrewBear, Perks & Co. Ltd (the attic floor, a signwriters' shop and canteen, was added in 1928).

The new building contained showrooms, offices, workshops and stores. On the fourth floor were the main administrative offices, and the boardroom, panelled in Italian walnut with an Ionic pilaster order. Plant was installed to draw sawdust and waste wood into a destructor, which fed the central-heating system throughout the works; the destructor chimney-shaft survives. (fn. 43)

In the 1930s stores and a garage were erected on the site of the Aylesbury Street houses, between the old and new buildings, but plans for a three-storey works extension were abandoned shortly before the Second World War.

Aylesbury Street to Skinner Street

The frontage here formerly belonged to the Seckford Charity estate, extending to St James's Walk and Woodbridge Street. The estate generally is discussed in Chapter II. More than half the frontage is taken up by the former Nicholsons' Distillery, the freehold of which was sold in the 1870s; most of the other buildings here remained in the charity's ownership until a hundred years later, when the bulk of the estate was acquired by the London Borough of Islington.

Excepting the remains of the distillery, there is little of architectural interest. Three old houses survive at Nos 181–185. No. 221 is the former Golden Anchor public house, 'improved and enlarged' in 1828 as part of the Sekforde estate redevelopment centring on Sekforde and Woodbridge Streets. (fn. 44)

Two corner sites are occupied by factory or warehouse speculations of the inter-war period. Nos 175–179, on the corner of Aylesbury Street, were built in 1931 for the Seckford Charity. At the top of Sekforde Street, and extending over the sites of Nos 1–33 Corporation Row, is the former warehouse and showroom of the Ingersoll Watch Co. Ltd, Nos 223–227. A speculative development, this was designed by Stanley Waghorn, architect, for Gilbert Waghorn, both of Adam Street, Strand, and completed for Ingersoll, whose logo is picked out in green and cream mosaic over the St John Street elevation (Ills 285, 291). The builders were W. H. Gaze & Sons Ltd. (fn. 45) In 1995–6 the building was converted to flats (sold as unfinished 'shells'), with a basement car park. It was named Pattern House, having been Condé Nast's Vogue pattern factory in the 1950s. (fn. 46)

Sekforde Court, at Nos 213–219, is an office development of 1985–8. (fn. 47)

Nicholsons' Distillery site. The gin distillery of J. & W. Nicholson closed in the late 1950s, and in the late 1990s was partially rebuilt and converted to apartments. The façade dates partly from 1828 but is mainly of the later nineteenth century.

John and William Nicholson, the founders, came into the trade through their cousin John Bowman, who by 1800 was established as a distiller and wine and brandy merchant in Coppice Row, Clerkenwell. The Nicholsons joined him there in partnership about 1802. In 1808–9 the Nicholsons set up on their own account as distillers in Woodbridge Street, approximately on the site now occupied by Woodbridge Chapel. (fn. 48)

286. St John Street, Sekforde Street and Woodbridge Street from the air, 2002, looking south-east. Nos 206–212 (Paramount House) at centre, with Percival Street Estate behind

Just prior to the rebuilding of the Seckford estate, the Nicholsons' premises had been enlarged to include a warehouse and stabling in Woodbridge Street, and a house in St John Street, on the later distillery site. (fn. 49) Much of the works had to be pulled down for the estate redevelopment, (fn. 50) and in 1828 a new distillery, the core of the later complex, was erected on St John Street (see Nos 199–205 below). In time, Nicholsons' came to occupy the greater part of the block bounded by St John Street, Sekforde Street and Hayward's Place. In 1833–4 Nicholsons built a warehouse on Woodbridge Street, (fn. 51) and a few years later acquired more land there. (fn. 52) By 1848 the White Horse public house in St John Street had been converted into a warehouse for Nicholsons, (fn. 53) and in 1849–50 their stables (at the rear of houses in Hayward's Place) were rebuilt on a larger scale, in a 'very substantial' manner with a 3ft-deep iron tank on top, holding 40–50,000 gallons of water. (fn. 54) The basement of the stable block survives (see below).

Considerable expansion and rebuilding took place following the purchase of the freehold of the site from the Seckford Charity in 1873. New offices were built in the 1870s and 80s (the present Nos 191–197 St John Street). Meanwhile, the original 1828 range adjoining was extended to the north, almost doubling it in length. The St John Street frontage was completed by the construction of Nos 187–189 in the 1890s.

287. Nos 199–205 St John Street, part of Nicholsons' Distillery, in 1953

288. Nos 183–205 St John Street in 1990, showing archway leading to Hayward's Place. Michael Cliffe House (Finsbury Estate) in distance

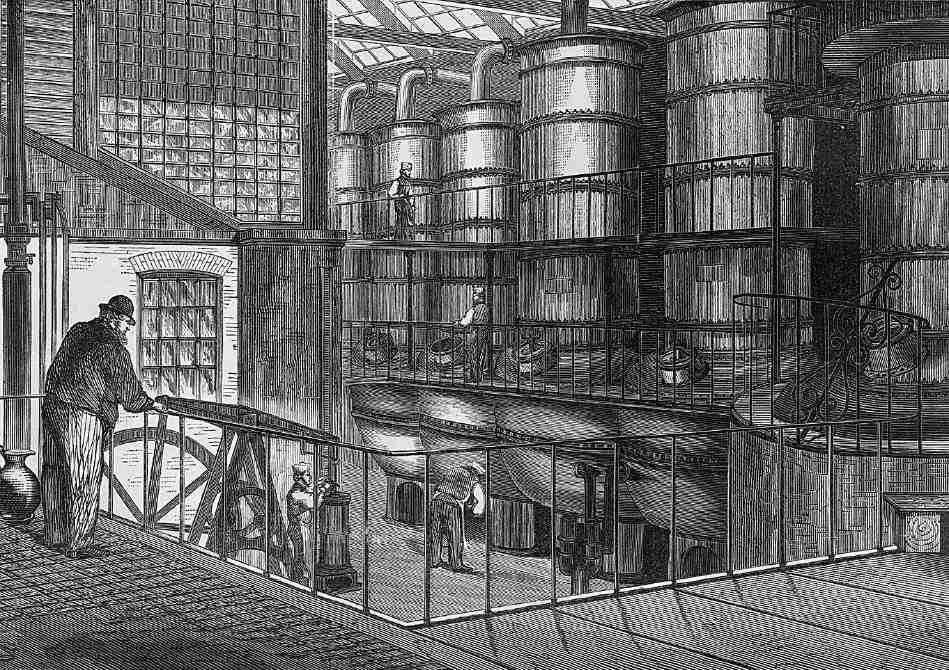

289. Nicholsons' Distillery, still room, 1860s

290. Nicholsons' Distillery, basement of former stables in 1998

Nicholsons remained a family business until after the Second World War, but following its takeover by the Ind Coope group the whole of the Clerkenwell premises was put up for sale in 1961. Photographs taken at the time show unremarkable, anonymous industrial interiors. (fn. 55) Thereafter the buildings were occupied mainly by firms in the meat trade.

In 1997–8 the former distillery was redeveloped as apartments by Bellway Homes North London under the collective name St Paul's Square. The architects were Clague, of Canterbury and Ashford. (fn. 56) The St John Street frontage was left essentially intact, and the 1838–9 rear boundary wall also preserved, but the central part of the site was opened up, with two new blocks crossing it from east to west. The buildings are divided into four groups— Farringdon, St John, Stirling and Woodbridge Courts— and together comprise 85 apartments, with underground parking. (fn. 57) The surviving historic fabric is described briefly below.

Excepting an infill building at the north end of the site, part of the Bellway development, the St John Street frontage of the former distillery is made up of three linked blocks, numbered 187–189, 191–197 and 199–205 St John Street (Ills 287, 288). The northernmost, Nos 199–205, was built in two phases: the first, comprising the seven southern bays, in 1828. The architect was John Blyth, and the builders Messrs Webb. (fn. 58) One of the most important industrial buildings surviving in Clerkenwell, this belongs to the austere monumental tradition of design typified by dock warehouses of the period. The building fronting the road was itself a warehouse, the stills being in a separate building at the Sekforde Street end of the site (Ill. 289). (fn. 59) As originally completed, the cornice and pediment carried the name nicholsons distillery and the date in relief lettering. This was lost when the upper part of the front was rebuilt in 1961, prior to the sale by Ind Coope. (fn. 60)

The other six bays, in similar style, were added in 1875–6, probably by the architect George Low, who had recently designed the tall range adjoining, Nos 191–197. This extension is not a precise match, the bays and windows being slightly wider than in the old part, and the basement openings wider, with camber-arches and keystones rather than flat heads. The entire block is constructed of yellow brick with stone and stucco dressings. Together with the 1990s infill building, it now comprises St John Court.

Low's range at Nos 191–197, again in yellow brick and stone dressings, was also built in two phases. The northern half, with the wider central bay containing the archway, was erected in 1873–4 as offices, by George Dines of Pimlico. The rest of the building followed in 1882–3, in the same style but overseen by different architects, Crickmay & Son, of Westminster and Weymouth, and executed by a different builder, W. Bangs of Bow Road. This second phase was essentially the rebuilding of two houses used by Nicholsons as a wine warehouse. The ground floor of this extension was fitted up as an office and sample room, the upper floors as living accommodation. (fn. 61)

At the rear of Crickmay & Son's building were the stables of 1849–50, of which the basement still exists. The brick-arched floor above is carried on cast-iron columns of cruciform section (Ill. 290). The upper part of the building has been largely or entirely rebuilt and now comprises apartments in Stirling Court.

Finally, the southernmost block (Nos 187–189) was added, probably in 1894. This building, which incorporates a passageway through to Hayward's Place, is of yellow and white brick and stone dressings, with a grey granite ashlar facing to the ground floor; the mansard floor was added as part of the Bellway development. It was evidently designed to match the now-demolished wine vaults built along the north side of Hayward's Place following the acquisition and demolition of the houses there by Nicholsons in 1882. (fn. 62) This and the preceding block now comprise Farringdon Court.

At the back of the distillery site, fronting Woodbridge Street, the 'substantial decorative' wall, erected in 1838–9, was also designed by the Nicholsons' architect John Blyth (see Ill. 73 on page 77). There were originally chevaux-defrise along the top, a feature which caused annoyance at the Seckford Charity, especially with the estate surveyor, James Noble, who took great exception to its 'prison-like' appearance and thought it would prejudice letting on the estate. (fn. 63) The wall now encloses apartments in Woodbridge Court.