Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Clerkenwell Road', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp385-406 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Clerkenwell Road', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp385-406.

"Clerkenwell Road". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp385-406.

In this section

- CHAPTER XIV. Clerkenwell Road

- Planning and construction, c. 1857–78

- Building development, c. 1875–94

- South side: Goswell Road to St John Street

- St John Street to Britton Street

- Pennybank Chambers

- Britton Street to Turnmill Street

- North side: Goswell Road to St John Street

- St John Street to Farringdon Road

CHAPTER XIV. Clerkenwell Road

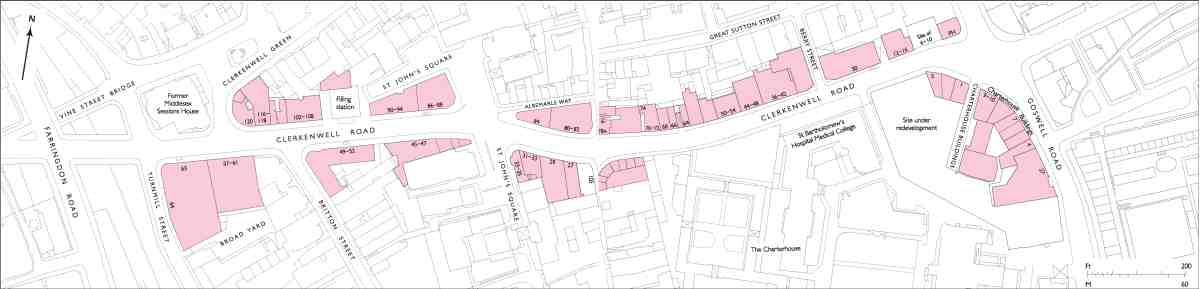

Clerkenwell Road and Theobalds Road were constructed by the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1874–8 as the central portion of an intended cross-capital arterial road, linking West End and East End. Less than half the route passes through the old parish of Clerkenwell. It is with this section that the present chapter is specifically concerned—the eastern part of Clerkenwell Road, extending from Goswell Road to the parish boundary at Farringdon Road (Ills 546, 547).

For some of the way, between Goswell Road and St John Street, Clerkenwell Road was adapted from Wilderness Row, a street laid out in the late eighteenth century on the estate belonging to the Charterhouse. The north side of Wilderness Row survived the improvement works largely intact, though the new road gave an immediate stimulus to rebuilding. The rest of Clerkenwell Road was completely new. Theobalds Road, in contrast, was almost entirely based on the existing street pattern (which included the original, relatively short, Theobalds Road).

Building on the cleared sites was in progress from the late 1870s, and took many years to complete—the last sites in Clerkenwell were not developed until the mid-1890s. In the summer of 1879 the Building News assessed the new structures going up along Clerkenwell Road and Theobalds Road, admiring Isaacs & Florence's 'quiet and dignified' Holborn Town Hall (in the Holborn portion of Clerkenwell Road), but concluding that 'On the whole, the new thoroughfare is not yet adorned by any work of striking architectural merit'. (fn. 1) No such work ever did appear, and many of the surviving nineteenth-century buildings along the road are indeed nondescript, though the shapes of several corner sites give some interest to otherwise unremarkable designs.

The present-day street numbering is based on the original odd and even sequences allocated in 1878, when the name Wilderness Row was abolished. The only main change in the Clerkenwell part of the road occurred in 1904, when the properties on the south side of Clerkenwell Road west of St John's Square were renumbered. This removed the confusion caused by the use of Nos 35a, b, c etc., for addresses between No. 35 and the Holborn Union Offices. The present-day numbering is used throughout the chapter.

Planning and construction, c. 1857–78

546. Clerkenwell Road, looking east from Farringdon Road, in 2001. Metropolitan Railway cutting and Vine Street Bridge in foreground

A new main road crossing central London from east to west, running through Clerkenwell to by-pass the City, had been recommended by the Parliamentary select committees on Metropolis Improvements in the 1830s and the Commissioners for Improving the Metropolis in the early 1840s. It was among the many schemes to which the new Metropolitan Board of Works turned its attention in the 1850s. The initial proposal, in 1856, was for a road connecting Old Street with Farringdon Road; this was soon expanded to include the widening of streets further west so as to join up with Vernon Place, New Oxford Street and Oxford Street. Additional improvements would carry the new route eastwards along Old Street and on to Shoreditch and Bethnal Green. Detailed plans for the socalled Old Street to Oxford Street Improvement were drawn up in 1857 by the MBW's architect Frederick Marrable, and a few years later the northern Middle Level Sewer was constructed along the proposed way. The road itself remained on the board's intended projects list and, after lobbying by the local vestries, was eventually provided for in the Metropolitan Street Improvements Act of 1872. (fn. 2)

547. Clerkenwell Road, from Farringdon Road to Goswell Road

The only long stretch of new road needed was between Back Hill in Holborn, just east of Leather Lane, and St John Street. To the west, Liquorpond Street, King's Road and Theobalds Road were widened, and a short link was constructed between the west end of Theobalds Road and the junction of Vernon Place with Southampton Row. The easternmost section of the road was made by widening Wilderness Row and opening up Pardon Passage, the alleyway connecting it with St John Street.

All in all, Marrable's route was followed with only minor alterations, though consideration was briefly given to one major departure—taking the road north rather than south of the Middlesex Sessions House. The straighter, southern route prevailed, chiefly because of an awkward gradient on the north side. It also gave the opportunity to clear away the slums of the 'Little Hell' neighbourhood between the north ends of Turnmill and Britton Streets. (fn. 3)

Either way, there was no avoiding the historic centre of Clerkenwell. As well as despoiling St John's Square, the new road meant the destruction of the early eighteenth-century houses along the south side of Albemarle Street and the north end of Britton Street. One especially venerable if degraded relic that had to be pulled down was the Jacobean house on the west side of the square, once inhabited by the celebrated Bishop Burnet (page 119). The only buildings in this vicinity which the final route took care to avoid (for financial reasons) were Gilbert & Rivington's extensive printing works and a Wesleyan Chapel, both in St John's Square, neither of them historic monuments. (fn. 4)

Construction began with the widening of Wilderness Row, where some recently erected warehouses on the south side, at the corner of Goswell Road, were pulled down in 1874. This part of the roadway was completed in May 1875 by the contractor J. J. Griffiths. (fn. 5) Buildings along the route through Clerkenwell west of St John Street were cleared by July 1877, and the roadway, constructed by J. Mowlem & Co., was completed in April 1878. The girder bridge carrying the road over the Metropolitan Railway was erected in 1875–6 by the Darlaston Bridge & Roofing Co. (fn. 6) In May 1878 the roads east and west of Gray's Inn Road were named Clerkenwell Road and Theobalds Road, and the whole of the roadway was finished and opened to the public by August. (fn. 7)

Building development, c. 1875–94

Building on the clearance land alongside the new roads was controlled initially by the Works and General Purposes Committee of the MBW, working in conjunction with the Superintending Architect, Marrable's successor George Vulliamy (whose approval was required for plans and elevations of intended buildings). (fn. 8) Development was carried out under building agreements leading to the issue of eighty-year leases on completion of carcases, and many lessees subsequently opted to buy the freehold as well. Plots west of St John Street were open to tender from the summer of 1878—the handful of cleared sites on the south side of the former Wilderness Row had already been let. But by the end of the following year the board admitted that take-up had been disappointing, attributing this to the depressed state of business generally. (fn. 9) A possible additional factor was the nature of the road itself, which in places cut awkwardly across existing streets, leaving some very small plots, 'too shallow for any but an inferior class of tenement property'. (fn. 10)

The new buildings were mostly warehouses or factories, though the board was required by law to allocate some ground for dwellings to make up for the many homes lost through the clearances. (fn. 11) In the Clerkenwell part of the improvement the only dwellings built were relatively small developments: Pennybank Chambers at Nos 31–33 and Javens Chambers at Nos 110–114.

The first sites to be built up were at the ends of the former Wilderness Row in 1877–9: shops and baths on the corner of St John Street, and warehouses on the corner of Goswell Road. Between St John Street and Farringdon Road four sites had been taken and built on by the end of 1881, three of them also in prominent positions: a goldchain factory at No. 84, on the apex corner with Albemarle Street; Pennybank Chambers, on the corner with St John's Square; and the Sessions House Hotel at No. 120, curving round into Clerkenwell Green (Ills 549, 559, 584). But progress generally was slow, and eventually, in July 1883, the board put the freeholds of the remaining sites up for auction, free of building restrictions. The few unsold plots were disposed of shortly afterwards by private treaty. (fn. 12) Of fourteen Clerkenwell lots, ten went to two purchasers— Frank Statham Hobson, a land agent, and H. & E. Kelly, a Hampstead-based building firm. Neither became involved in construction, selling or letting their ground for others to develop. (fn. 13) Most of the vacant plots were built up between 1885 and 1888, the remaining gaps being filled in over the next few years. The last was between Britton Street and Turnmill Street, where Nos 57–61 were built in 1893–4, nearly two decades after the site had been cleared.

South side: Goswell Road to St John Street

While the north side of the former Wilderness Row was left untouched by the incorporation of the thoroughfare into Clerkenwell Road, the south side was not. But it was not completely cleared, because of recent road-widening and building at the eastern end (from the Master's garden at the Charterhouse to the corner of Goswell Road). Faced with the prospect of heavy claims for compensation, the MBW decided against further widening this part of the road to match the rest of the route, and settled for what looks today like a penny-pinching and unsatisfactory compromise. Part of the new development was cleared in order to round off the awkward junction with Goswell Road and Old Street, but otherwise the newly established line of frontage was left alone, and continued westwards to St John Street, where again the corner was rounded off.

548. Nos 8–10 Charterhouse Buildings and 1–5 Clerkenwell Road in 2007. Thomas Chatfeild Clarke, architect, 1877–9

549. No. 84 in 2004. Ebenezer Gregg, architect, 1879

550. No. 27 in 2007; Samuel Parr & Alfred Pope Strong, architects, 1879

Late Victorian Commercial architecture, Clerkenwell Road

551. Nos 70–74 in 2006; a warehouse of c. 1876

552. Nos 102–108 in 2004; King family, developers, 1888–90

553. Nos 86–88 in 2006; warehouses of 1884–6 (now The Zetter hotel)

554. Nos 35–43 (originally St John's Buildings) in 2006; James Barrett, builder, 1890–1

This stretch of the road has little visual cohesion. The corner buildings erected on the MBW's cleared sites at either end are still standing, but the other Victorian buildings have gone and the frontage between is largely taken up by the boundary wall of the Charterhouse and St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical College building of the 1950s. The remaining large site, adjoining the college, was cleared following wartime bomb-damage and is only now (2006–7) being redeveloped.

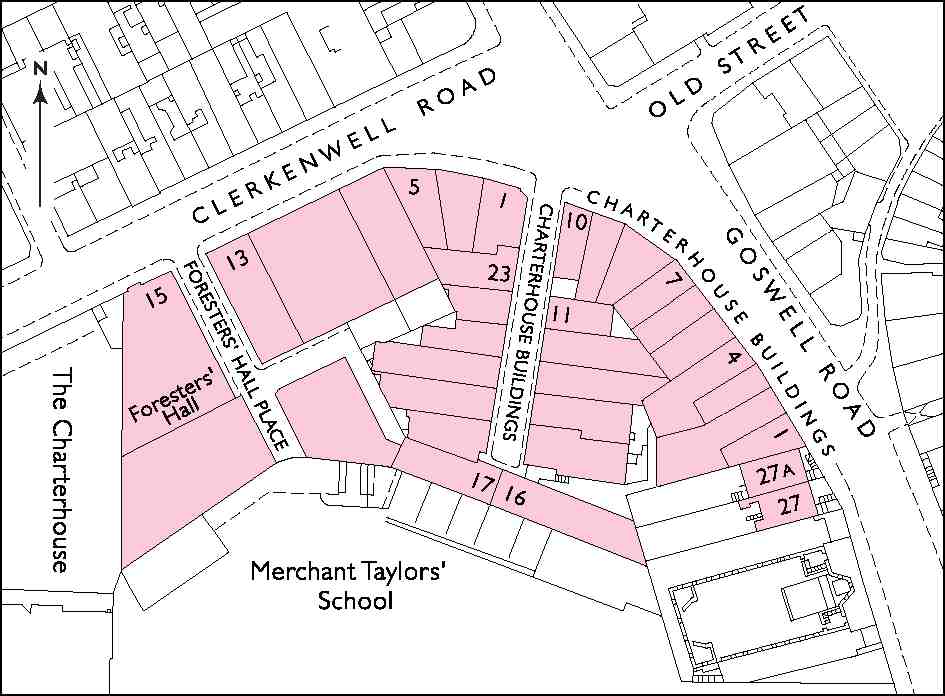

Charterhouse Buildings and Foresters' Hall

The stimulus for building on what is now the southern corner of Clerkenwell Road and Goswell Road was the departure of Charterhouse School to Godalming and the sale of the old premises at the Charterhouse to the Merchant Taylors' Company as a new home for its own school. Part of the attraction was the spaciousness of the grounds. But given the Merchant Taylors' limited funds, and the need for alterations and extensive new building, a substantial part of the site, mostly playground and including the valuable frontages to Wilderness Row and Goswell Road, had to be let or sold for development.

The property was conveyed to the Merchant Taylors in two lots, the intended building ground in 1868 and the remainder a few years later. In 1869 a small piece fronting Goswell Road was bought by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners for building two adjoining vicarages: one for St Thomas's Charterhouse, immediately to the south of the plot (see page 277), the other for St Mary's Charterhouse, in Playhouse Yard, between Golden Lane and Whitecross Street. (fn. 14) At the same time, a deal was struck with two City warehousemen, Henry Thomas Tubbs and Joseph Lewis, for the development of the rest of the building ground. (fn. 15)

Tubbs and Lewis built up most of the ground themselves, initially taking leases of the new buildings and subsequently exercising their option to buy the freeholds of both built-up and still-vacant plots. Their buildings were designed by the architect John Collier. (fn. 16) At the west end of the ground a vacant plot was sold by them to the Ancient Order of Foresters friendly society for a regional headquarters 'hall', and with this exception all the new buildings were warehouses or factories. The hall stood on the corner of a new roadway, Foresters' Hall Place, connecting Wilderness Row with the Merchant Taylors' School.

Building was well advanced by the time that the MBW's plans for the Old Street to Oxford Street Improvement were finalized. The opportunity had been taken by the MBW in 1868 to widen this end of Wilderness Row, with a ten-foot strip bought from the Merchant Taylors. When Clerkenwell Road was subsequently laid out, the MBW decided against further widening, the new and expensive Foresters' Hall being a particular deterrent. Consequently, this stretch of the road is only fifty feet wide, rather than sixty as elsewhere along the route. (fn. 17) Nevertheless, several of the new warehouses had to be pulled down in order to improve the junction with Goswell Road. George Vulliamy was responsible for the rather excessive cutting back of the corner, settled in 1872. Bazalgette, the MBW's engineer, hoped to redraw the line when the time came to make up the road in 1874, but by then it was too late. A change at that stage would have required the consent of Tubbs and Lewis (worsted by the board over their extravagant claim for compensation the year before), and this was not forthcoming. (fn. 18)

Of seven warehouses in Wilderness Row acquired by the MBW only five were demolished. The others, unfinished at the time of acquisition, were completed by the MBW in 1874 (Nos 16 and 17 Charterhouse Buildings, later 7 and 9 Clerkenwell Road). The demolition and roadbuilding left the MBW with two building plots on the new corner, at the top of an access road to Tubbs and Lewis's warehouses on part of the back land. These sites were built up in 1877–8 with more warehouses.

Illustration 555 shows the disjointed pattern of building. Initially, the intention was to divide the ground from east to west with a road parallel to Wilderness Row. In the event only a short length of this road was needed, forming a side-turning from Foresters' Hall Place behind Nos 11 and 13 Clerkenwell Road. (fn. 19)

555. Clerkenwell Road—Goswell Road corner, c. 1913

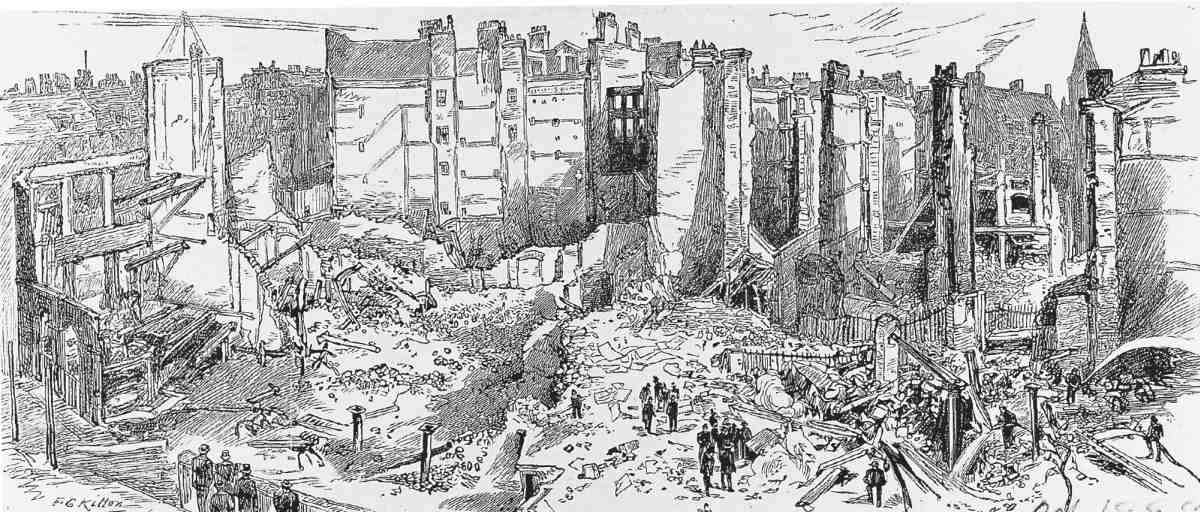

Of the original development by Tubbs and Lewis of 1870–4 only a fragment survives: Nos 4–7 Charterhouse Buildings in Goswell Road, erected in 1870. Many of the buildings were destroyed by fire in 1885. In this conflagration, reportedly the biggest London had seen since the Tooley Street blaze of 1861, the warehouses were reduced to rubble, their walls burst apart by the expansion of the iron floor-beams (Ill. 556). (fn. 20) Their replacements, and several more of the buildings, including Foresters' Hall and the two vicarages (Nos 27 and 27A Goswell Road) suffered heavy bomb-damage in the Second World War and had to be demolished. Much of the vacant land was acquired by St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical College for building on, but remained vacant for many years, used only as parking space. (fn. 21)

556. Aftermath of the fire at Charterhouse Buildings, October 1885

Redevelopment of this site, which extends from Clerkenwell Road behind Charterhouse Buildings to Goswell Street, began in 2006. The new buildings, collectively called Charterhouse the Square, comprise flats and some commercial spaces, together with a cardiac and cancer research centre for Bart's Hospital. (fn. 22) Thornsett Group are the developers, the architects Capital Architecture and the main contractor is Ardmore.

Nos 8–10 Charterhouse Buildings and 1–5 Clerkenwell Road. Though designed by the same architect, Thomas Chatfeild Clarke, these two groups of warehouses are not stylistically a matching pair (Ill. 548). They were built for the respective purchasers of the sites from the MBW: the eastern block (Nos 8–10 Charterhouse Buildings) in 1877 for Charles McCarthy, a hat manufacturer of Ludgate Hill, the western in 1878–9 for Michael McSheehan, a house agent of Finsbury Square. (McSheehan's warehouses also included No. 23 Charterhouse Buildings at the rear, now demolished.) The contractors in each case were Merritt & Ashby. (fn. 23)

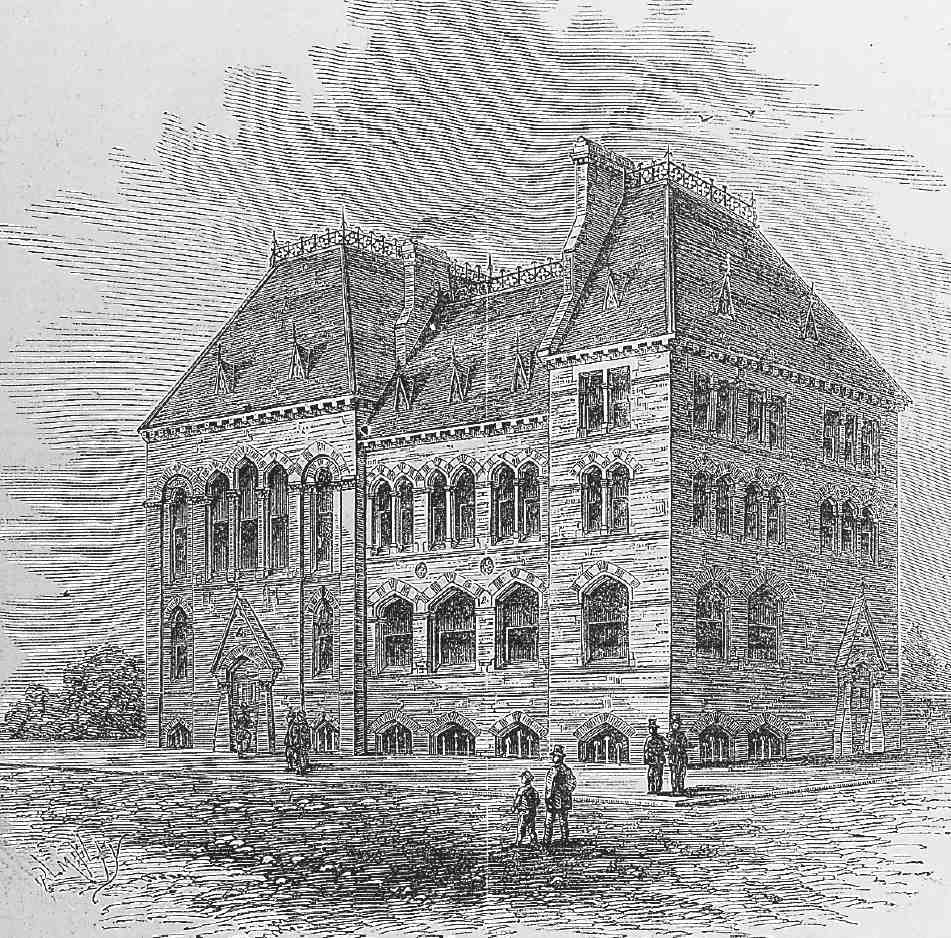

No. 15, Foresters' Hall (demolished). This was built in 1870–2 as the headquarters and meeting-hall of the London United District of the Ancient Order of Foresters friendly society, but largely rebuilt a few years later. (fn. 24) The original building was designed in competition by W. L. Gomme, civil engineer and surveyor, a Forester himself. (fn. 25) Owing to some dispute with the building committee, Gomme had no part in the execution of his plans, which was superintended by a firm of surveyors, George Lansdown & Pollard. The builder was William Henshaw, another Forester. The foundation stone was laid on 12 April 1871 by the Lord Mayor of London, Thomas Dakin, and the building opened on 11 January 1872, having cost around £8,000, excluding the £4,500 paid for the site.

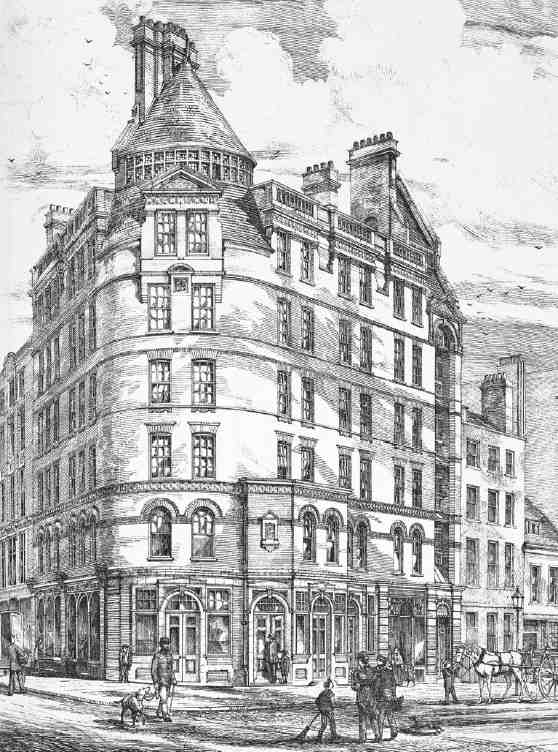

557. Foresters' Hall, No. 15 Clerkenwell Road. W. L. Gomme, architect, 1870–2. Demolished

Eclectic in design, Foresters' Hall was brick-built with stone Gothic porches, windows with straight-sided arches and a high, French-style roof (Ill. 557). Besides offices, a boardroom and a caretaker's apartment, it contained a galleried meeting-room able to accommodate 600. The meeting-room was top-lit, with a lay-light ceiling of ground-glass panels in iron framing, and its walls were ornamented with pilasters and a figured openwork frieze doubling as ventilation grilles. The Builder was unimpressed—'certainly the ugliest apartment we have looked at of late years'. (fn. 26)

In 1874 the Foresters purchased the site at the rear, with the intention of enlarging the hall and erecting warehousing for rent. The enlargement was carried out c. 1878 by John Collier, whose designs appear to have superseded those drawn up in 1874 by another architect, Frank Thicke: the hall was almost entirely rebuilt and raised in height to make a much bigger meeting-room (occupying most of the building above the ground floor). (fn. 27) The site at the back remained vacant until 1895, when a warehouse was erected there by a speculative builder, James Kent, and let to Perry Gardner & Co., printers and bookbinders. In 1898 Perry Gardner took over most of Foresters' Hall, inserting floors in the meeting-hall to make three storeys of workshops there, and the two buildings were thrown into one. By that date Perry Gardner also occupied the warehouse next door, No. 13 Clerkenwell Road. (fn. 28)

Foresters' Hall and the warehouse behind were bombed in the Second World War. The site is now occupied by part of St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical College science block (to be described in a separate monograph on the Charterhouse). (fn. 29)

Nos 17–23 (with Nos 102–106 St John Street)

The south-eastern corner of Clerkenwell Road and St John Street is occupied by a late-1870s speculative development originally incorporating baths for swimming and bathing, as well as houses and shops (Ills 558, 579). The 'Central Bath' establishment was short-lived, and this part of the building was subsequently adapted as an electroplating works.

The buildings, faced in white brick with stone and moulded-brick dressings, were designed by Robert Walker, district surveyor for St Martin-in-the-Fields, and built by J. J. Bennett & Co. in 1877–8. (fn. 30) The principal developer appears to have been Alfred Bompas, gentleman, of Barnsbury, who applied for the site to the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1876, took the lease of the completed buildings in 1878, and attempted to purchase the freehold in 1879. (fn. 31) However, a published account of the new buildings states—as if the matter were open to question—that the works were carried out 'under the personal direction' of Bennett & Co., 'who are the originators and owners of the baths'. (fn. 32) Bompas was not, according to his referees, in a position to finance the undertaking on his own account, and his relationship with Bennetts is not known. (fn. 33)

The development consisted of six houses, five with shops, and the swimming-pool and baths behind, with its entrance at No. 104 St John Street. From the entrance (which retains its bracket lamps, though not the original ornamental iron cresting), a wide corridor led to the swimming-pool. Covered by a glass roof, this measured about 90ft by 30ft, with a 7ft deep-end. The pool was white-tiled and had an ornamental dolphin's head fountain on one side. Ranged along the poolside were dressing-boxes and 'other conveniences', and above were galleries on two levels each with fourteen private baths for men and women respectively. A demountable floor allowed the pool to be used for meetings during the winter, swimming—even indoors—being evidently still a seasonal recreation. (fn. 34)

558. Nos 17–23 Clerkenwell Road and 102–106 St John Street in 2007

The baths closed in 1896, and from then until the 1970s were occupied by E. C. Furby & Sons, electroplaters and enamellers of bicycle parts, the old slipper baths giving way to plating baths. (fn. 35) Furby's premises were reported destroyed by fire in 1919. (fn. 36) Nothing of the original pool and baths survives today.

St John Street to Britton Street

For No. 25 Clerkenwell Road, see No. 105 St John Street on page 214.

No. 27

This small warehouse and workshop (Ill. 550) was erected in 1879 for William and Francis Hudden, tin-plate workers and hardware merchants of St John's Lane, whose firm continued to trade there until the late 1950s. The architects were Samuel Parr and Alfred Pope Strong of Finsbury Square, the builder John Grover of New North Road. (fn. 37)

No. 29

The original building, a bicycle factory of c. 1888, was occupied from 1906 by the shopfitters E. Pollard & Co. It was rebuilt for Pollards in 1919–20 as their 'City' showrooms; the present granite and timber shopfront is later and was probably added by the firm in the 1930s. (fn. 38)

Pennybank Chambers

This corner block, comprising Nos 31–33 Clerkenwell Road and 33–35 St John's Square, was erected in 1879–80 by the National Penny Bank Co. Ltd and provided shops and artisans' dwellings, as well as a branch for the bank (Ill. 559). It was designed by the architects Charles Henman and William Harrison, and built by Aitchison & Walker of St John's Wood. The foundation stone was laid in May 1879 by HRH Princess Christian of SchleswigHolstein (who received a commemorative trowel, inlaid with silver pennies and the figure of a workman with a bank book, illustrating 'the power of the penny'). (fn. 39)

559, 560. Pennybank Chambers, Nos 31–33 Clerkenwell Road and 33–35 St John's Square, in 2006. Charles Henman and William Harrison, architects, 1879–80

561. Pennybank Chambers, original design, 1879

Although run as a commercial venture, the National Penny Bank was in its origins philanthropic, continuing a tradition of penny savings banks established principally in Scotland and Yorkshire from the 1840s. The founder and manager, (Sir) George Bartley, had been involved with Lord Shaftesbury and others in promoting penny banks in the late 1860s, and the National Penny Bank Co. Ltd, formed in 1875, was intended to put the movement on a firm financial footing. Pennybank Chambers (originally Penny Bank Buildings) was only the second building specially erected for the company, which was supported by many prominent and high-ranking figures. (fn. 40)

When opened in August 1880, the ground and first floors comprised three shops and the bank itself, the latter occupying the corner and front to the square. A fireproof floor of rolled iron and concrete separated this commercial section from the four floors of dwellings. These were two- and three-room tenements, four to a floor, with shared WCs on the landings. Illustration 561 shows the building as proposed. The prominent dovecote-like corner feature was intended as a laundry, but was omitted from the final design and a cheap rooftop structure of wood and corrugated iron provided instead. As usual in such blocks, the flat roof was used as a drying-ground. (fn. 41) The building is faced in stock and red brick, and is ornamented with terracotta friezes incorporating the bank's penny-piece emblem (Ill. 560). (fn. 42)

The Clerkenwell branch, one of more than a dozen across London, closed in the late 1880s, though the National Penny Bank Co. continued to own the building until it was wound up in 1914. (fn. 43) The lower floors continued in business use, mostly in connection with the jewellery and clock trades, but by 1960 the dwellings were standing empty. In 1977–8 the entire building was refurbished by the London Borough of Islington as craft workshops for the Clerkenwell Green Association. (fn. 44)

Nos 35–43

The corner shop at No. 35 and the adjoining range of shops and warehousing at Nos 37–43 (formerly called St John's Buildings) were built in 1890–1 by James Barrett, a Stepney builder, apparently as his own speculation (Ill. 554). Early occupants included jewellers, electroplaters, and the National Society of Lithographic Artists & Engravers. (fn. 45)

Nos 45–47

This very plain warehouse was built in 1886–7 for the printers Gilbert & Rivington of St John's Square, replacing their old machine-shop which pre-dated the creation of Clerkenwell Road. The architect was W. Seckham Witherington, and the builders were Patman & Fotheringham. (fn. 46)

Nos 49–53, former Holborn Union Offices

562, 563. Nos 49–53 Clerkenwell Road in 2007; brickwork by Mark Gentry

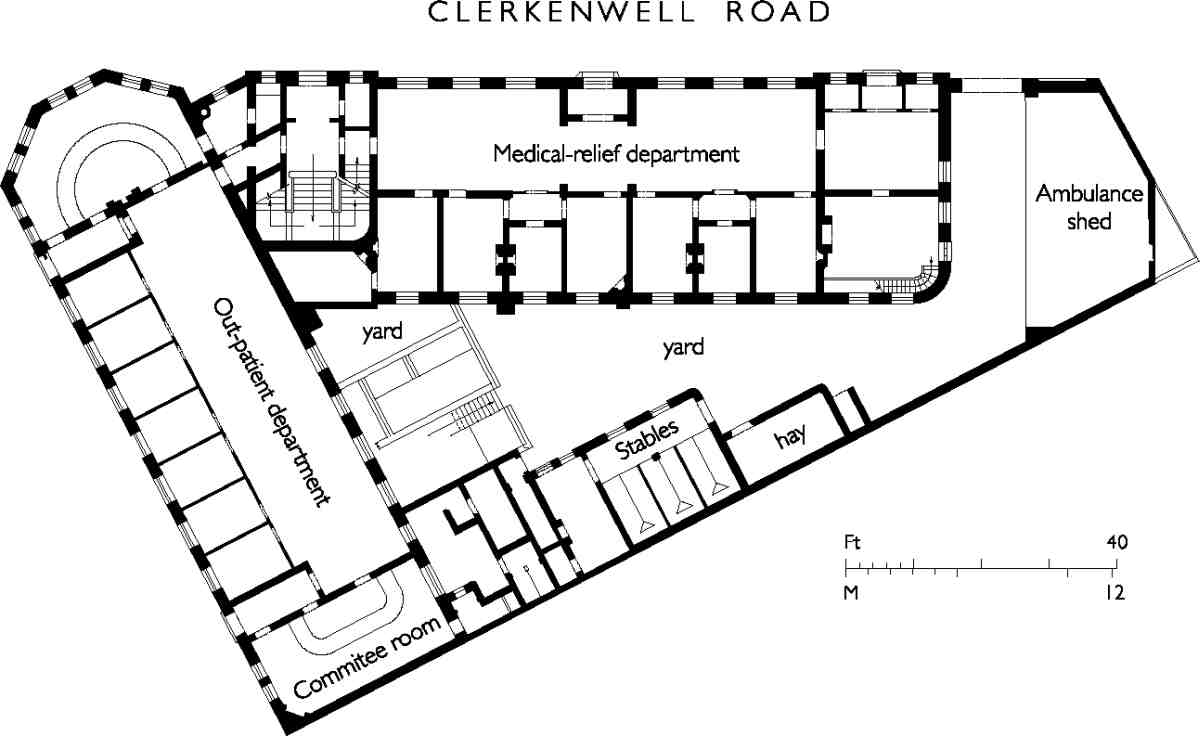

Now converted to flats, this Queen Anne-style building on the corner of Britton Street was erected in 1885–7 as administrative offices and medical and out-relief departments for the Holborn Union Board of Guardians. The architects were H. Saxon Snell & Son. Executed in fine quality brickwork with much moulded detail, it is a rather more cheerful-looking building than is usually associated with this prolific firm of workhouse and hospital specialists (Ill. 562).

Clerkenwell had been absorbed into the Holborn Poor Law Union in 1869, and its old workhouse in Farringdon Road was demolished in 1883 (see Survey of London, volume xlvii). For a while it was intended that the Farringdon Road site should be used for new offices and workhouse accommodation, and steps were also taken to acquire a house in Clerkenwell Green as a dispensary and out-relief station. These schemes were abandoned when the offer of the present site was received from Frank Statham Hobson, the land agent who had recently bought this and several other Clerkenwell Road clearance sites from the Metropolitan Board of Works. The new offices, dispensary and relief station were accordingly built in Clerkenwell Road, and the additional residential accommodation needed was provided in a new workhouse at Mitcham, where the Union already had schools (also designed by Saxon Snell & Son). (fn. 47)

564, 565. Nos 49–53 Clerkenwell Road, interiors in 1993. The former boardroom and (right) outpatients' waiting-hall and examination rooms

In June 1885 the tender of Mark Gentry, an Essexbased contractor and brickmaker, was accepted at £16,490, inclusive of fixtures and fittings. The foundation stone was laid in December 1885, and the first board meeting took place in the new building on 1 June 1887. (fn. 48)

Several features of the design were decided by the Guardians, probably with economy in mind—stone dressings, a tower and a balustraded parapet were all rejected. At least one small extravagance, however, was included, a gallery overlooking the boardroom, the most ornately treated room (Ill. 564). When the building had been completed, and the question of whether ratepayers should be allowed in to the gallery during board meetings was raised, someone seems to have noticed that it had not been shown in the original plans, and Henry Snell was taken to task. He pointed out that the original plans bore little resemblance to what had actually been built, adding: 'Our recollection (which we confess to be now somewhat dim) is that the arguments adduced in favour of the gallery were that "if it were not required it need not be used"'. (fn. 49)

566. Nos 49–53 Clerkenwell Road, ground-floor plan as built, 1855–6

The building consists of two main ranges—one facing Clerkenwell Road with a fairly grand, symmetrical front, and a plainer wing facing Britton Street, with a canted bay on the street corner. The façades are finished in bright orange-red rubbed brick (on a plinth of blue engineering brick), almost certainly made at Gentry's own brickworks at Hedingham in Essex, and with plentiful cut and moulded brick decoration, such as swags of fruit and flowers (Ill. 563). The Britton Street range has a little wooden cupola with a weather-vane.

Inside, the ground floor contained the out-relief and medical-relief departments, each with a large waitingroom giving on to rows of rooms for interviews or examinations, and a committee room where applications were considered (Ills 565, 566). A dispensary at the eastern end communicated directly with a medicine store in the basement. Administrative offices, more committee rooms and the boardroom were situated on the first floor, via an imperial staircase, and further office space was provided in a low-ceilinged attic storey in the Clerkenwell Road range. In the Britton Street range, a mezzanine gallery overlooked the out-relief department waiting-room (Ill. 565). The yard at the rear and side contained stabling and a shed for an ambulance to transport paupers from here to the Mitcham infirmary or other Union buildings. (fn. 50)

Following the Poor Law reorganization under the Local Government Act of 1929, Holborn Union Board of Guardians was dissolved and its responsibilities transferred to the London County Council. Thereafter, the building was one of the LCC Relief Offices, and later a Divisional Health Office, before being taken over in the 1960s by Islington Borough Council Engineer's Department. The Red House, as it had become known, was converted into residential units in 1994–5 by Croft Homes Ltd (Michael Sierens Associates, architects). (fn. 51)

Britton Street to Turnmill Street

The cleared ground here was bought at the Metropolitan Board of Works' auction in July 1883 by the Hampstead builders H. & E. Kelly for £15,100. (fn. 52) They disposed of the site over a ten-year period, beginning with the Turnmill Street corner, sold in 1886 to the Great Northern Railway Co. 'after much negotiation' for £14,400. (fn. 53) Today the only one of the original buildings left on this part of the road is the large block of stables built by the GNR and later converted into a warehouse for Booths the distillers (Nos 63 Clerkenwell Road and 64 Turnmill Street).

No. 55, on the corner of Britton Street, was leased in 1889 to Robert Griffith of Camberwell, gentleman, who erected a warehouse there, first occupied and subsequently purchased by a firm of bookbinders. The building was bombed in the Second World War and the site redeveloped in the 1950s with Booths' Red Lion Distillery. It was redeveloped again in the 1990s as No. 1 Britton Street, an apartment block (see page 171).

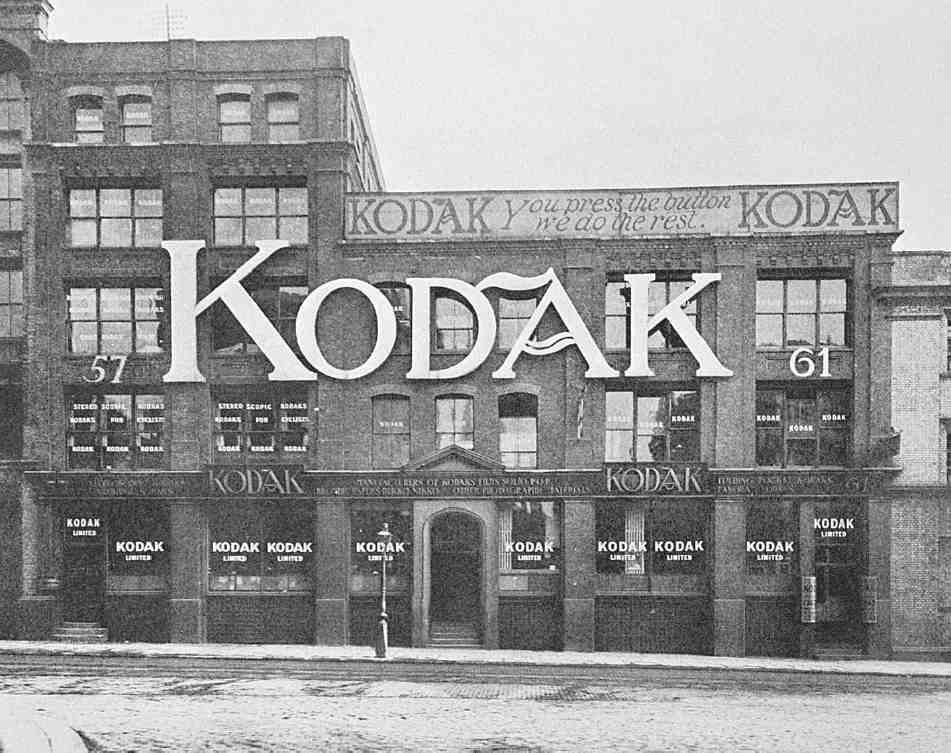

The Kellys' remaining ground here was developed in 1893–4 by a solicitor, Edward Humphreys of Grover, Humphreys & Son, with two warehouses, Nos 57 and 59–61. Erected by Killby & Gayford, these were fairly plain, substantial buildings, Nos 59–61 having a large extension at the rear backing on to Broad Yard (Ill. 567). (fn. 54) They were first occupied as a factory and warehousing by Salmon & Gluckstein Ltd, to supply their fast-expanding chain of tobacconist shops, and in the late 1890s became the European headquarters and distribution centre of Kodak. The Kodak headquarters, which has long been demolished, is of interest for rooms designed there by George Walton, then recently established in London. Like so much of his work for the company these had only a brief existence. Kodak left in 1911, and the buildings, bombed in the Second World War, were replaced in the early 1950s. (fn. 55)

Red Lion Distillery (demolished)

The Red Lion Distillery was built after the Second World War for the gin-makers Booths, by then part of the Distillers group, to replace the long-established distillery in Turnmill Street, which had been badly damaged in the war (see page 197). It was designed in 1956 by the Engineering Division of the Distillers Co. Ltd of Glasgow, and although completed seems not to have been in full operation when Lord Kinross's history of Booths was published in 1959. (fn. 56) One of the last industrial buildings of architectural quality to be built in the area, it had only a short life, being closed in the 1970s and demolished about 1990 (see Ill. 571). The name was taken from the pre-1936 name of Britton Street or from the original Red Lion tavern, which occupied the corner of Red Lion Street and Clerkenwell Green, just north of the distillery site, before the creation of Clerkenwell Road; the lion, however, seems to have been an emblem long used by the Booth family.

Curving round the street corner, the building was clad in red sand-faced bricks, with tall stone-dressed windowbays rising through the several floors and offering glimpses of the copper stills. Over each bay a square stone panel carried a lion passant in relief. A central atrium gave views of the manufacturing processes on each floor. (fn. 57)

Kodak headquarters at Nos 57–61 (demolished)

At the beginning of 1898 the Eastman Photographic Materials Co. Ltd, the British company set up by the founder of Kodak, George Eastman, was in the process of transferring its head offices and wholesale depot from Oxford Street to what was then No. 43 Clerkenwell Road. By June, the new premises had been fitted out 'with every modern appliance that money can buy or ingenuity suggest', including a steam-powered system for heating and air-conditioning. Cameras and film from America or the Eastman factory at Harrow were despatched from here for individual orders, and there were also departments for developing and enlarging. On the first floor were a 'handsome' boardroom, reception room, private rooms for managers, and offices. (fn. 58) In 1901 Kodak also took over No. 41 (later 57), where Salmon & Gluckstein had remained in occupation, knocking the two buildings together the following year. (fn. 59)

George Walton's association with Kodak was a consequence of his acquaintance over several years with George Davison, a director and assistant manager of Eastman Photographic Materials, and later Kodak's head of European sales. As an amateur photographer, Davison was closely involved in the exhibitions of the 'Linked Ring', an artistic secession from the more technically minded Royal Photographic Society. In 1897 he commissioned Walton to design a photographic exhibition for Eastmans at the New Gallery, Regent Street, and also employed him about this time to decorate his house in East Molesey. Over the next few years, Walton did much work designing Kodak shops under Davison's patronage. (fn. 60)

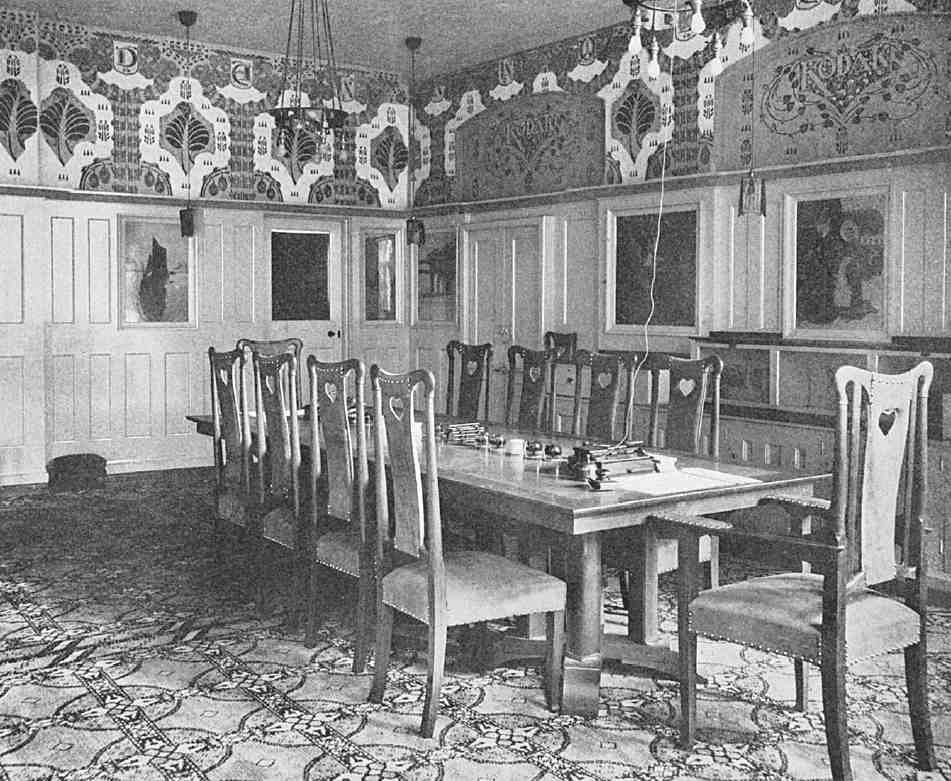

567–569. Kodak's European head offices and depot, Nos 57–61 Clerkenwell Road, in the early 1900s. Interiors of c. 1898–1900 by George Walton: the boardroom (middle) and showroom (below). Demolished

It seems unlikely that all of Walton's work at Clerkenwell Road was done in 1898, as has been thought. Of the two known schemes, the boardroom (Ill. 568) may possibly have been the one mentioned above in June 1898, but was perhaps a later remodelling or replacement. (fn. 61) The new showroom was officially opened in September 1902, and it may be that the boardroom also dated from this later period. (Perhaps significantly, the 'Cholmondeley' chair, which apparently saw its first use in the boardroom at Clerkenwell Road, was not registered as a design by Walton until 1902.) (fn. 62)

Decorated in a scheme of old gold, the showroom had a stencilled frieze based on the signs of the zodiac, and was furnished in fumed oak (Ill. 569). In the boardroom the colours were 'soft lavender', cream and green; here, too, was a stencilled frieze, incorporating the name Kodak. (fn. 63)

After Kodak's departure in 1911 to a new head office at Kingsway, the Clerkenwell buildings were taken over by Murrays the confectioners in connection with their Fleet Works in Turnmill Street. (fn. 64) Badly damaged during the Second World War, they were replaced in the early 1950s by the lower part of the present building, erected for Klug & Sons, furniture makers, to designs by Westmore & Sanders, architects. Booths the distillers took over the building in 1953, the upper storeys being completed for them in the early 1960s. Now called Fleet House, it was altered and enlarged as offices in 1999–2000 by Clarke Associates for Bee Bee Developments. (fn. 65)

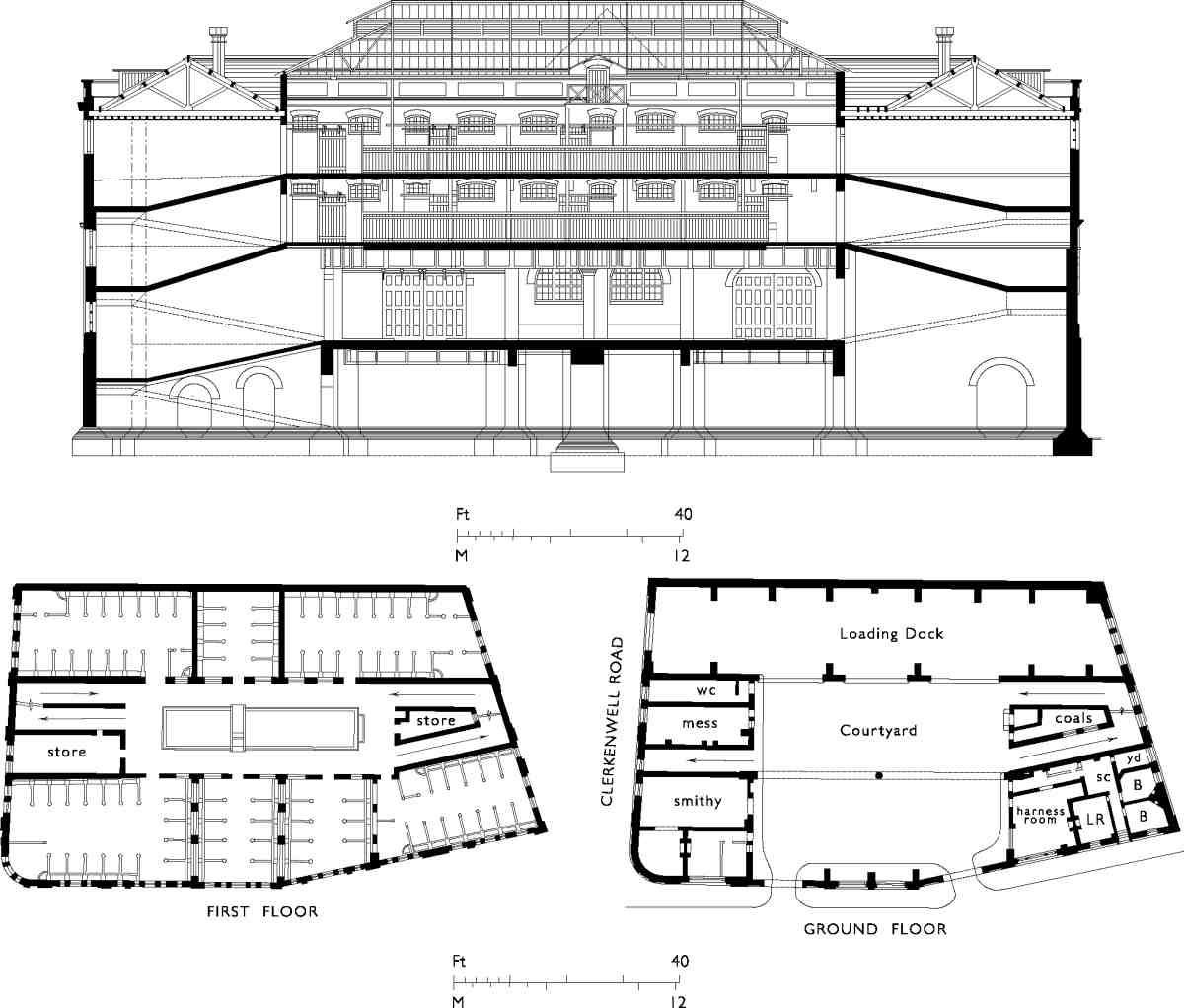

Former Great Northern Railway stables, Nos 63 Clerkenwell Road and 64 Turnmill Street

This building was erected in 1886–7 to provide warehousing and stables for the Great Northern Railway Co., as an adjunct to their main goods depot at Farringdon Station. It was designed by the GNR's Engineer, Richard Johnson, and built by Kirk & Randall of Woolwich at a contract price of nearly £29,500. (fn. 66) The ground floor was planned on quadrangular lines as a large top-lit yard with In and Out gateways on Turnmill Street, surrounded by ancillary rooms and a loading dock with a crane and a hydraulic hoist for taking vans and goods to and from the basement. The stables, approached by ramps, occupied the two upper floors and could accommodate about 190 horses (Ill. 570).

Construction was largely of stock brick, with a plinth of Staffordshire blue brick, the street fronts being faced in white brick with red brick dressings (Ill. 571). Much ironwork was used, especially in roofing over the courtyard, which has a central column of 1¾-inch cast iron carrying plate girders 43 ft 3 ins long, and the roof over the light-well is carried on wrought-iron trusses. The specifications required the rolled-iron girders to be obtained from Dorman Long & Co., of Middlesbrough, and some other ironwork from the St Pancras Iron Co. The floors generally, including the iron-and-concrete horse ramps, were covered in metallic paving supplied by the Wilkes Metallic Flooring & Eureka Concrete Co. Ltd of Devonshire Square, grooved and channelled and spread with two or three inches of broken brick or ballast. The hoist, a late addition to the design, adding more than £1,500 to the cost, was made by Tannett Walker & Co. (fn. 67)

570. Former Great Northern Railway stables, Nos 63 Clerkenwell Road and 64 Turnmill Street, plans and section. Richard Johnson, engineer, 1886–7

571. Former Great Northern Railway stables, Nos 63 Clerkenwell Road and 64 Turnmill Street. View from northwest in 1966; to the left are Nos 57–61 Clerkenwell Road and the now demolished Red Lion Distillery

The GNR's successor, the London and North Eastern Railway, continued to use the building for stabling and warehousing until the mid-1930s, when it was taken over by Booths as warehousing for their wine department. Booths remained there until the 1970s. (fn. 68) Since 1985 the building has been occupied as a club and venue known as Turnmills, reportedly the first club in England to have a 24-hour licence. Turnmills quickly acquired a glamorous reputation, attracting international stars including Michael Jackson and Madonna, as well as the former gangster 'Mad' Frankie Fraser, who was shot and wounded there in 1991. (fn. 69) The Spanish restaurant Gaudi, designed by Nigel Coates in the style of Antoni Gaudí, opened at No. 63 Clerkenwell Road in the 1990s. Externally, the building has been altered little, though it has lost the original pitched roof and clock-gable over the Turnmill Street front.

North side: Goswell Road to St John Street

Wilderness Row, from which this part of Clerkenwell Road was formed, was laid out in the late eighteenth century and took its name from the 'wilderness' garden separating the Charterhouse from its small estate to the north. It was built up with houses in two phases: the eastern half, between Goswell Road and Berry Street, in 1771–8, and the western half between 1784 and 1798. (For a fuller account of Wilderness Row, see Chapter X.) Beyond the western boundary of the estate the roadway petered out into a narrow alley leading to St John Street (see Ills 390, 394 on pages 283, 285). The whole of the north side of Wilderness Row was left alone by the Metropolitan Board of Works in laying out Clerkenwell Road, but inevitably the new road created pressure for redevelopment. Some reconstruction had taken place even before the road opened, with the building of the Criterion Hotel on the corner of St John Street. However, a number of the original houses survived into the twentieth century (Ill. 575). None are now left, but the Hat and Feathers pub and three houses predate the creation of Clerkenwell Road, if only by a few years.

These houses, Nos 64–68, preserve an impression of the original development of Wilderness Row, and were very old-fashioned when built in 1861—though appropriate to what was then a mere backwater (Ill. 573). Their architect was named as C. F. Maltby, and the builder was probably Thomas Ennor. (fn. 70)

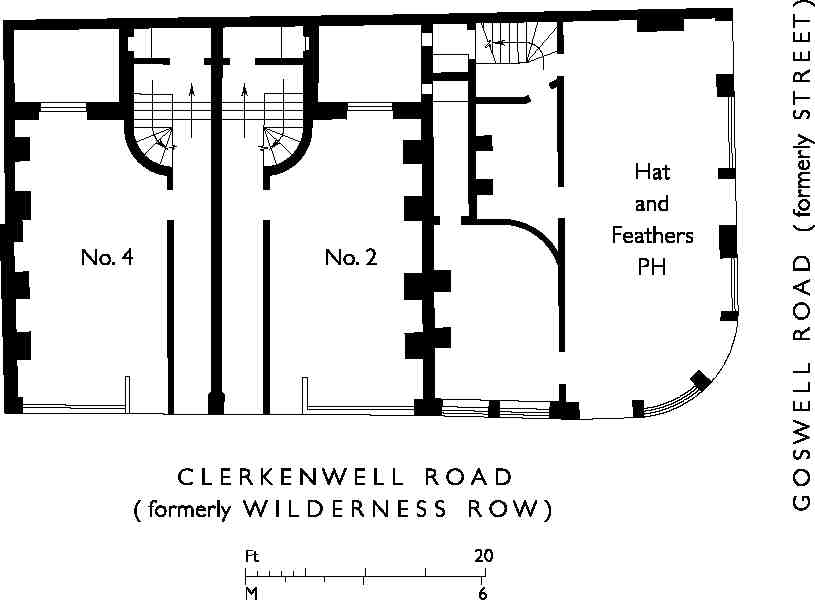

572. The Hat and Feathers public house, and Nos 2 and 4 Clerkenwell Road. Ground plan as rebuilt in 1860

573. Nos 64–68 Clerkenwell Road in 2006; C. F. Maltby, architect, 1861. These are the only houses of Wilderness Row to survive from before the Victorian road improvement

No. 2, the Hat and Feathers

The present building, replacing an old tavern of the same name, was erected in 1860 for the publican, James Leask. Like its predecessor it was originally numbered in Goswell Street (now Goswell Road), taking its present address from one of a pair of houses with shops adjoining, rebuilt at the same time. No. 2, an eating-house, was amalgamated with the Hat and Feathers in the early 1880s; the other house, No. 4, has been demolished. Illustration 572 shows the original layout of the buildings. (fn. 71)

Leask's architect was William Finch Hill of the pub and music-hall specialists Finch Hill & Paraire, and the builder was also a Mr Hill. The façade—'gay without being crude' (fn. 72) —is decorated with Classical statues, urns and richly ornate capitals and consoles (Ill. 574). The groundfloor front is probably largely original, the polished granite pilasters being added in 1897 to replace timber ones. (fn. 73) The facia, extending across the front of the former eatinghouse, is of twentieth-century date.

At the time of writing (2007) the building has not long been re-opened as the Hat and Feathers Bar and Restaurant, having stood empty or been occupied by squatters since about 1990.

574. No. 2 Clerkenwell Road, the Hat and Feathers, in 2006. William Finch Hill, architect, 1860

Factories and warehouses

The present buildings are mostly former factories and warehouses, varying in date between the 1870s and the 1960s. Many were built in connection with the clock and watch trades, which were well established in Wilderness Row by the early nineteenth century.

Nos 6–10, designed by Edward Haslehurst and built in 1899–1900 for J. J. Stockall & Sons as a clock and watch factory (see Ill. 575), was demolished about 1986; the site is still vacant at the time of writing. (fn. 74)

Nos 12–16 (formerly Grayson House), by Richard Seifert & Partners, was built in 1959 for E. Gray & Son, watchmaterial dealers; the front was remodelled during refurbishment about 2002. (fn. 75)

No. 30, now the Vitra furniture showrooms, was built in 1955 (as Nos 18–30) for Class & Son, to designs by Wright & Tidmarsh. It was initially occupied by a clothing manufacturer. (fn. 76)

Nos 32–34, built about 1962, was first occupied for some years by a firm of watch-strap makers. (fn. 77)

575. Tramlines being laid at junction of Goswell Road and Old Street, 1906. The tall building left of the Hat and Feathers is Stockall & Sons' clock and watch factory at Nos 6–10 Clerkenwell Road

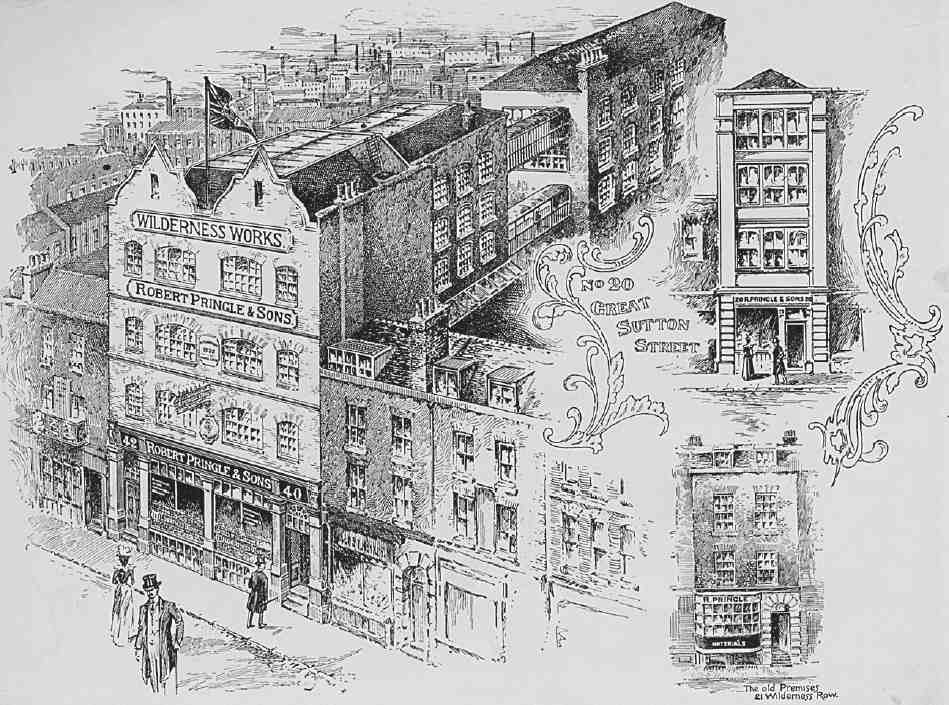

Nos 36–42, together with No. 20 Great Sutton Street, formerly comprised Wilderness Works, the factory and warehouse of the old-established Clerkenwell firm Robert Pringle & Sons, one of the largest wholesalers in the country for the jewellery, silverware and clock and watch trades. From c. 1868, Pringles were at No. 21 Wilderness Row (later 42 Clerkenwell Road), taking over No. 40 Clerkenwell Road in 1884. Wilderness Works was built in 1897–8, and initially consisted of the block at Nos 40–42, connected by bridges to the Great Sutton Street building (page 292). In its original form it was in the Queen Anne style, with two Dutch gables on the Clerkenwell Road front (Ill. 576). An extra storey was added in 1907–8, and in 1936–7 the works were extended over the sites of Nos 36–38, the 1890s front being remodelled as part of the present symmetrical façade. The shopfront was supplied by the local firm of Pollards. Gordon Pringle, a member of the family, was the architect. On opening in 1938 the works contained fourteen departments including jewellery and watchmaking, repairs, electroplating and silversmithing. (fn. 78)

576. Nos 36–42 Clerkenwell Road, Robert Pringle & Sons' Wilderness Works, c. 1898

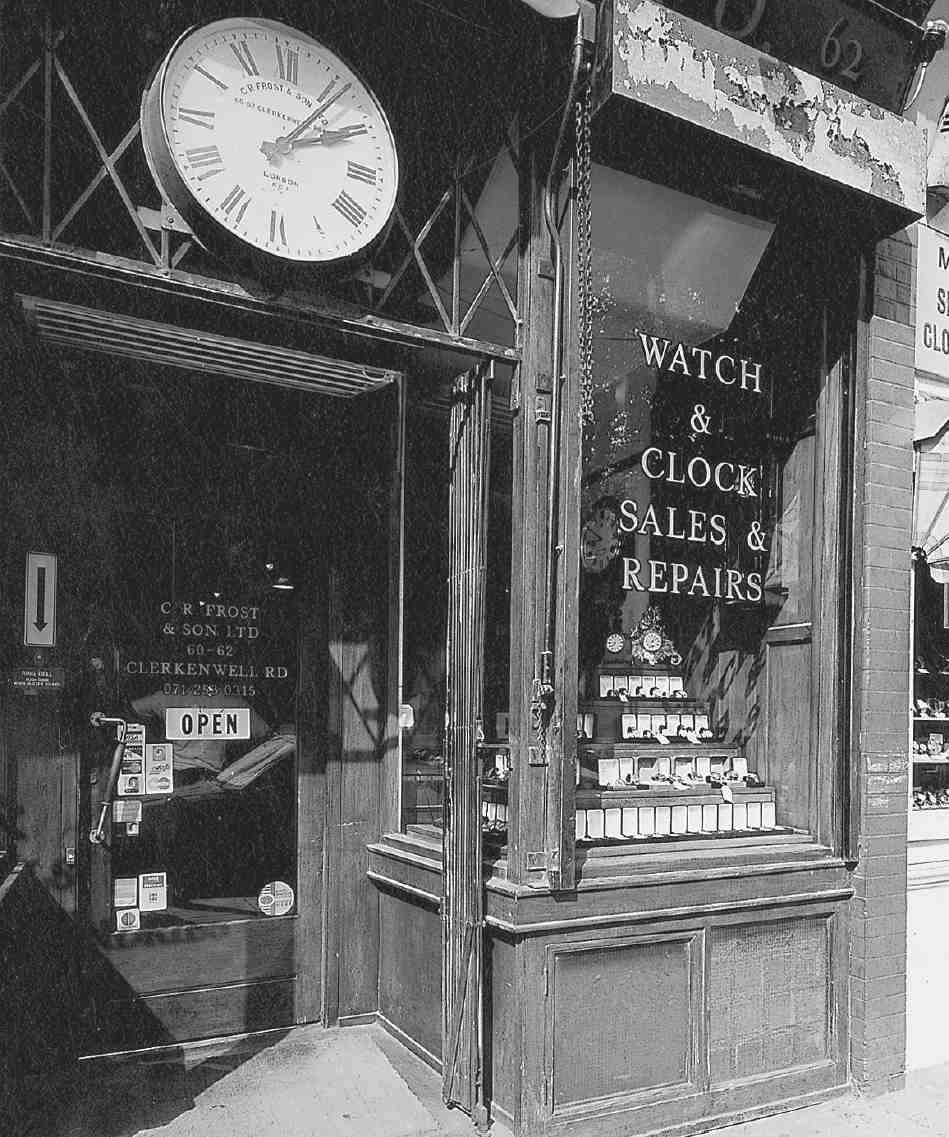

577. Nos 60–62 Clerkenwell Road, shopfront in 1999

Nos 44–48 date from 1933 and were built as a factory for Elias Korn, jeweller and watchmaker. The architect was W. Ernest Jefferis. (fn. 79)

Nos 50–54 and 56–58 were designed by Herbert Wright and built as a speculation by the developers Class & Son in 1932–4. (fn. 80)

Nos 60–62. This warehouse dates from 1909–10, and was built by Spiers & Son of St John's Wood for the developers, Benjamin Goldberg Gruntwag and Jonas Alexander Morton. The rather knocked-about front elevation, faced in high quality red brickwork and with one original decorative rainwater head, has an Arts-andCrafts character; the architect's name is not known (Ills 577, 578). (fn. 81)

Nos 70–74, comprising two shops (Nos 70 and 72) and warehousing or factory space above and to the rear (No. 74), seems to have been built in the mid to late 1870s, when Wilderness Row was being made into part of the new Clerkenwell Road. (fn. 82) The original occupants included businesses established for some years in the old buildings on the site—a fruiterer and an engineer in the shops, and a firm of bookbinders at No. 74—George and Edward Byworth & Co., who remained until the 1890s and may have been the developers. It is constructed partly of iron, with boldly decorated cast-iron panels and brackets at the front (Ills 551, 579).

578. Nos 60–62 Clerkenwell Road in 2006

579. Clerkenwell Road, north side, looking east from St John Street, in 2004. From left to right: former Criterion public house; Nos 76–78; Nos 70–74. Part of Nos 17–23 and 102–106 St John Street, on south side, at right

Nos 76–78. Before the building of Clerkenwell Road, the site was occupied by a large building fronting St John Street and with a long flank to Pardon Passage, the premises of David Duffield & Co., linen-drapers. The western portion, fronting St John Street, was rebuilt in 1875 as the Criterion Hotel (see below), but the rest of the premises, fronting Clerkenwell Road, continued in Duffields' occupation until the mid-1890s, when it was replaced by the present building. This was remodelled in 1995 by the architects Munkenbeck & Marshall as a photographic laboratory for Metro Imaging, with an atrium and a barrel-vaulted studio on the roof for daylight photography (see Ill. 579). (fn. 83)

No. 78A, and Nos 116–118 St John Street

With the creation of Clerkenwell Road, the obscure site on what had been the north side of Pardon Passage became a main street corner. The owners of the Cannon Brewery in St John Street were quick to take advantage, building the Criterion Hotel here in 1874–6, as a replacement for the Red Lion and Punchbowl at No. 118 St John Street. This old tavern itself survived as a shop, but was eventually replaced in the 1920s by the present two-storey extension to the Criterion, matching the style of the 1876 building. The Criterion closed in the 1960s, becoming a watch-materials shop and then, in the late 1990s, a restaurant. The former Criterion is a showy, Italianate building, typical of the period, faced in white brick with white stone dressings (see Ill. 579). (fn. 84)

St John Street to Farringdon Road

Nos 80–82

The original buildings were erected about 1888 and first occupied by wholesale grocers Phillips & Co. In 1896, No. 80 was converted into a coffee tavern and workmen's temperance hotel, called Pearce's Dining and Refreshment Rooms, later part of the British Tea Table chain. It was latterly occupied partly as the Myddelton Hotel, which closed in the mid-1930s, and partly by Butler & Crispe, wholesale patent-medicine warehousemen. (fn. 85) At No. 82, Phillips & Co. were succeeded by Butler & Crispe, who had not long been there when the premises were destroyed by fire, in November 1896. (fn. 86) Both No. 80 and the rebuilt No. 82 were burned out during the Second World War. The present building is largely a reconstruction of 1949 for Butler & Crispe, designed by Gordon H. Inman, of Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn. (fn. 87)

No. 84

Edward Culver, a gold-chain maker and jeweller in business in Spencer Street since the 1850s, was among the first to tender for a plot on the new road, offering to spend £8,000 on extensive premises. Plans for his new factory and warehouse, designed by Ebenezer Gregg, were accepted by the MBW in January 1879 and the building was completed that October by George Baker & Son of Lambeth. Extra-deep foundations required because of the sub-soil pushed the cost up to £11,000. Culver remained at the premises until about 1894, when he removed to Myddelton Street. (fn. 88)

Occupying the narrow, apex site at the junction of Clerkenwell Road and Albemarle Way, the building is faced in a mixture of stock brick, stone and wire-cut red brick, with twisted iron columns at the windows. The top floor is set back slightly, behind a latticework stone parapet decorated with tall urns (Ill. 549). The Classical-style entrance dates from 1915, when the ground-floor and basement were converted to use as a branch of the London County & Westminster Bank (by Percival H. Burr, architect). (fn. 89)

Nos 86–94

This site was developed by Charles Bryant, a builder of Highbury New Park, in 1884–6. (fn. 90) Of the five fairly plain warehouses or factories he built, only two, Nos 86–88, survive. Nos 90–94 were destroyed in the Second World War and replaced c. 1957 by the present building. Erected for the typesetters B. Dellagana & Co. Ltd, this has recently been converted (by GML Architects) to apartments, with commercial premises on the ground and lower-ground floors (Ill. 580). (fn. 91)

580. Nos 90–94 Clerkenwell Road, newly completed in 1957

Nos 86–88, occupied for many years by Zetters Pools, were converted in 2002–4 into The Zetter hotel for the restaurateurs Michael Benyan and Mark Sainsbury. The new 59-room hotel, designed by Chetwood Associates, was described as 'super-green', its design, construction and energy sources conforming to the latest environmentally friendly principles—recycled plastics, for instance, were used as wall-cladding (Ill. 553). The rooms are arranged around a central glazed atrium with a spiral staircase, the rooftop suites having private terraces. (fn. 92)

No. 96 (demolished)

The original building, a brush factory, was erected in 1886–7 for Charles A. Watkins, proprietor of Hamilton & Co. Watkins moved on after a few years rather than carry out alterations required by the London County Council, and the building was subsequently occupied by S. Hildesheimer, art printers and publishers. It was destroyed by bombing in 1941. The site, with that of Nos 98–100 (see below), is now occupied by a filling-station. (fn. 93)

Nos 102–108

These two stone-faced buildings (Ill. 552) are the survivors of a row of three late Victorian warehouses, first occupied by the Salvation Army for its publishing and international trading activities. Subsequently, from shortly before the First World War until the 1930s, Nos 102–108 played an important role in the development of the British recording industry as the headquarters and studios of the Columbia Graphophone Co. Ltd.

581. Salvation Army International Trade Headquarters, Nos 98–108 Clerkenwell Road. King family, developers, 1888–90. Nos 98–100 demolished

582. A Columbia Graphophone Co. showroom at Nos 102–108 Clerkenwell Road, probably in the late 1920s

The development was carried out by members of the King family, City-based surveyors and architects, who each took one warehouse. In 1888–90 the two eastern warehouses, Nos 98–100 and 102–104 were erected by William Stubbs of Lambeth for William Isaac King and Edwin Franklyn King, who had acquired the site from the Hampstead contractors H. & E. Kelly. Despite their height and relatively expensive stone facing, the warehouses were not of fireproof construction, and had ordinary wooden floors and matchboarded walls. (fn. 94) The new buildings were taken by William Booth on 21-year leases, and used for the production and printing of the War Cry and other publications, and the manufacture, packing and despatch of musical instruments, uniforms and tea. (fn. 95)

The third warehouse, Nos 106–108, was built in 1890 by Mark William King soon after his purchase of the site. This had not been part of the Kellys' ground, but was bought from the MBW (through the speculator Frank Statham Hobson) by Eli Javens of Clerkenwell Green, and sold on by him to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, probably for an intended parochial mission hall. Booth was again the lessee (Ill. 581). (fn. 96)

Continued expansion of the Salvation Army led to the transfer of the International Trade Headquarters wholesale department to new premises in Fortess Road, Kentish Town, in 1896, leaving the Clerkenwell warehouses to deal with retail orders. Printing was later moved to St Albans, and in 1911, on the expiry of the leases, the Salvation Army left for new trade premises at King's Cross, designed and built in-house. (fn. 97)

With the departure of the Salvation Army, the easternmost warehouse (Nos 98–100) was taken over by Markt & Co. of New York, importers of tools and hardware. At Nos 102–108 the party walls were opened up and the lower floors taken by Furnival & Co., manufacturers of printing machinery. The four upper floors, separated from Furnivals by a new fireproof floor, became the British and European headquarters of the Columbia Graphophone Co. Ltd. (fn. 98)

Columbia moved to the 'Columbia Building' (later called Columbia House) from City Road about the beginning of 1913. The new premises were fitted up with showrooms, sales and clerical offices, stock rooms, and recording facilities—including a band testing-room, recording laboratory and artistes' reception room. (fn. 99) At this time the British branch of Columbia was one of the two leading companies in the United Kingdom manufacturing and selling gramophone players and records, the other being the Gramophone Co. Ltd (His Master's Voice). Columbia came to lead the field in orchestral recordings, signing up (Sir) Thomas Beecham and Sir Henry Wood in 1915. In the 1920s W. S. Purser, Columbia's chief engineer, made the first electrical recordings in this country in his fourth-floor workshop at Clerkenwell, developing a microphone for recording from the regular acousticrecording sessions in the studio above. (fn. 100)

In 1926–8 Columbia expanded its Clerkenwell Road premises, taking over Nos 96 and 98–100, so as to accommodate newly acquired subsidiaries including the Johnson Talking Machine Co. and Parlophone records. The showroom in Illustration 582 may have been fitted up at this time. (fn. 101) In 1931, with the industry suffering from the Depression, Columbia and HMV merged to form Electric and Musical Industries Ltd (EMI). (fn. 102) The Clerkenwell Road studio proved too small and noisy for electrical recording, and by the early 1930s EMI recording was concentrated at Abbey Road.

In April 1941 Nos 98–100 and No. 96 were destroyed by enemy action, and by 1946–7 the company had relocated to Hayes (where the Gramophone Co. had built a factory in 1907): the remaining buildings at Clerkenwell Road served as a wireless supplies depot until their sale shortly afterwards. (fn. 103) Nos 102–108 were subsequently occupied by the Bell Punch Co. Ltd, manufacturers of ticket machines, adding machines and aircraft instruments, who remained there into the 1970s. (fn. 104)

Nos 110–114 (Javens Chambers)

This comparatively small block, fronted in red brick with Classical stone or cement dressings, was built about 1885 for Eli Javens, a 'modeller' with premises at the rear in Clerkenwell Green (see Ill. 583). Known as Javens Buildings, or Javens Chambers, it originally comprised two shops, for many years a dairy and a café, and half a dozen three-room flats above. (fn. 105)

583. Nos 116–118 Clerkenwell Road and part of Nos 110–114 on right, 1976

584. No. 120 Clerkenwell Road, Cornwell House, in 2004. Part of Klamath House (Nos 116–118 and No. 18 Clerkenwell Green) on right

585. No. 120 Clerkenwell Road, the former Sessions House Hotel. Ground plan, c. 1880

Nos 116–118

The present office building (Klamath House), erected in 1988–90, was designed by Chris Wilkinson Architects and won a commendation from the Royal Fine Art Commission. Situated close to the corner of Clerkenwell Green, it has mainly glass fronts to both streets (see Ills 584 and 93 on page 89). (fn. 106) It replaced a two-storey building of 1884, originally diamond-polishing workshops and offices (Ill. 583). (fn. 107)

Cornwell House (Nos 120 Clerkenwell Road and 20 Clerkenwell Green)

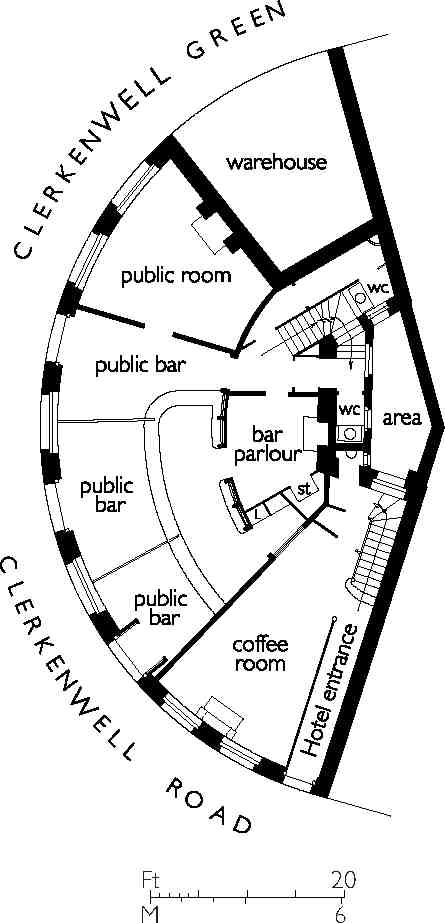

Occupying one of the most prominent sites on the new Clerkenwell Road, Cornwell House was built by Charles Powell, landlord of two pubs on Clerkenwell Green demolished for the improvement: the Jerusalem Tavern at the corner of Red Lion Street, and the Sessions House Hotel at the corner of Turnmill Street. Powell, who claimed to be well known to the local magistracy as a provider of refreshments when the court opposite was in session, undertook to rebuild the Jerusalem Tavern 'on an imposing scale', with accommodation for dining and luncheons. The plans were approved in March 1878, and the building had been completed by April 1880. (fn. 108) Although standing on the site of the Jerusalem Tavern, the new building took the name of the Sessions House Hotel.

The sweeping façade was finished in white brick, with dressings of red brick, stucco and polished granite (Ill. 584). Inside, the building was divided up in a roughly sectoral arrangement, with a separate entrance at the southern end giving access to the hotel rooms on the upper floors (Ill. 585). The northernmost part of the site was set aside for a warehouse (No. 20 Clerkenwell Green). (fn. 109)

The hotel closed about 1923, and in 1925 the building was turned into a spectacle factory, showrooms and offices for the General Optical Co., by the architect Herbert Wright. It was renamed Cornwell House, after the owners of the company, E. T. and F. U. Cornwell. In 1978–9 Cornwell House was refitted as craft workshops by the London Borough of Islington for the Clerkenwell Green Association. (fn. 110)