An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 2, East. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1932.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Kenchester', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 2, East(London, 1932), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol2/pp93-96 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Kenchester', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 2, East(London, 1932), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol2/pp93-96.

"Kenchester". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire, Volume 2, East. (London, 1932), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/heref/vol2/pp93-96.

In this section

44 KENCHESTER (A.c.)

(O.S. 6 in. (a)XXXIII, N.W., (b)XXXIII, S.W.)

Kenchester is a small parish on the N. bank of the Wye, 5 m. W.N.W. of Hereford. The remains of the Roman town of Magna and the church are the principal monuments.

Roman

a(1). On low-lying ground near the Wye, some 4½ miles W. of Hereford, can still be traced the outline of a town which, as Leland remarked, "is far more auncyent then Harford, and was celebrated yn the Romaynes tyme." The outline, now a flattened mound, forms a hexagonal plan and encloses an area of about 22 acres, which has been proved from time to time to contain abundant remains of Roman buildings. The site lies on the Roman road which joined Wroxeter to the N. with Caerleon and Caerwent to the S. and was, in the middle ages, known as Bot Street; whilst from E. to W. another road passed through it out of England into the middle reaches of the Wye valley and so into the Roman military frontier-system of Wales. The mileage of the Antonine Itinerary indicates with reasonable certainty that the Roman name of the town was Magni or Magnae or Magna—whichever be the nominative case of a word that has survived only in the dative or ablative Magnis. The name is possibly Celtic, connected, as Sir John Rhys thought, with maen, "a stone." If so, the masculine gender of the Celtic word may be thought to support the nominative Magni, but no great stress can, it seems, be placed upon this possibility.

Excavations of one kind or another have been carried out intermittently here, notably by the Woolhope Club in 1912–13 and 1924–25. Nevertheless, little is at present known either of the plan or of the history of the place. The defences included a masonry wall, a small and indeterminate fragment of which can still be seen in an orchard at the N.W. corner. Prior to 1861, more extensive fragments were visible, and the facing was described by T. Wright (Wanderings of an Antiquary, 1853) to consist of "small stones arranged in . . . herring-bone work and cemented together with mortar which is inferior to that usually found in the town-walls of the Romans." It is perhaps more probable that this masonry was core rather than facing, and modern observers have detected no trace of herring-bone. In 1925 a trench was cut across the line of the wall at the N. corner. The foundations were found to be "about 7 feet wide and consisted of rough cobbles set in clay. . . . The trench was continued down the slope to a distance of 80 feet from the wall through soil undisturbed, very hard and clayey, until the flat ground of the clover field at the foot was reached. But there was no trace of any ditch outside the wall. This corroborates what Stukeley said in 1722: 'There appears no sign of a fosse or ditch around it'" (G. H. Jack and A. G. K. Hayter, Excavations on the Site of . . . Magna, II, 7). The absence of a ditch requires explanation and may perhaps be due, at this point, to the proximity of a gate. Moreover, the surface indications suggest that the wall was backed by (or was added to) a bank, as at Caerwent, Colchester and elsewhere; and it is clear that the defensive system as a whole needs further investigation. The only hint as to its date is the alleged discovery, in 1796, of a milestone of the emperor Marcus Aurelius Numerianus (283–4 A.D.) in the foundations of the N. wall (see Woolhope Trans., 1881–2, p. 247; C. I. L. VII, 1165; V.C.H. Hereford, I, 181; the stone is now in the Hereford City Museum). If correctly described, this discovery implies that the wall, or this part of it, is not earlier than the end of the 3rd century, but the evidence cannot be accepted without reservation.

Of the gates, even less is known. Stukeley, in his plan dated 1721, shows four—one near each of the N.E. and W. corners, and one in each of the N. and S. sides. "He does not show a gate on the E. wall, but I am told that the owner of the site (Mr. Hardwick) uncovered the remains of a gate on this wall at a spot in line with the roadway uncovered by us. Some of the worked stones presumably belonging to this gateway are still to be seen in a field near Credenhill railway station. These stones are well squared and hold dimensions about 3 ft. by 1 ft. 6 in. by 1 ft." (Jack, Excavations . . ., I, 21).

Certain of the roads and streets have been more adequately investigated. Outside the site of the E. gate already mentioned, the main axial road of the town is thought to have branched into three—one branch proceeding directly eastwards, and the others bending northwards and southwards respectively. The southerly branch was trenched in 1920 and 1924 at points about 120 yards from the E. gate. The road was found to be 22 ft. wide and to consist successively, from top to bottom, of 3 ins. of small cobble stones, 2 ins. of coarse red sand, 7 ins. of larger cobbles, and 9 ins. of very hard gravel. There was an indication of a shallow gutter formed in the cobbles on both sides of the road. "Pottery of Flavian date was found below the surface of the road, and near the edge of it. Other fragments level with the top of the paving were of 2nd century date" (Jack, Excavations . . ., II, 9). Nearby, within a few feet of the edge of the cobbles, were discovered two human skeletons, a man and a woman, with fragments of pottery "which seems to suggest a 3rd-century date for the interments." On the top of the road-surface was a third skeleton, face downwards, "obviously a post-Roman interment." There were also traces of occupation in the vicinity. The easterly road was likewise examined, at a distance of 350 yards from the E. gate. The evidence was not altogether clear, but heavy cobble paving to a width of 28 ft. was revealed and seemed to be associated with pottery of c. 120–160 A.D.

Inside the walls of the city, two streets and possibly a third have been identified. The main axial street has been traced for a distance of about 800 feet, and its construction examined in some detail. It had a central groove or channel, and stone-lined lateral drains. The over-all width between the centres of the drains was about 30 ft., whilst, outside the E. gate, the cobble metalling, which was supported at the sides by heavy curb-stones, was 18½ ft. wide. The surface showed at least one main repair, and the original metalling had been set in lime, to form a sort of concrete. The central channel is noteworthy, but whether it should be compared with the central channel in the well-known Roman road on Blackstone Edge, Lancashire, may be questioned. The bedding of the northern lateral drain included stamped Samian pottery of late 1st-century date. Crossing this street at right angles near the centre of the town, was another street apparently contemporary with it. On the W. side of this second street was a well-built drain which had previously collapsed into an underlying rubbish pit containing Flavian pottery. A third street or passage with a narrow cobbled surface was detected at one point N. of the main street (see plan, Site 3).

The buildings, as at present known, do not admit of detailed description. In Stukeley's day, a fragment of masonry containing a half-domed niche, popularly called "the Chair," stood above ground within the N.E. corner of the site, and is illustrated in the Itinerarium Curiosum. Farther S., Stukeley marks the position of a "very fine mosaic floor" which had been found and destroyed a few years previously. Recent excavations have added two further mosaics (Pl. 135), one possibly of Antonine date, and the fragmentary plans of a number of buildings of various sorts; but in no case have the plans or history of these structures been worked out systematically. The main street was apparently, as we should expect, lined continuously with buildings which, towards the E. end, seem to have taken the form of the oblong "shops" that occur in similar positions at Caerwent and elsewhere. Behind and to the N., set obliquely to the main lines, are the fragments of a large building which was possibly a dwelling-house of some pretension. On the S. side of the main street, the buildings appear to have been fronted by a line of porticos, supported by wooden posts on masonry pedestals, as at Wroxeter. No temple or forum or other public building can yet be detected in this medley of scattered foundations. Nor, save in rare instances, is there any hint of chronology. A small room, in the large oblique building, covered pottery which suggested that it was "built possibly as early as the middle of the 2nd century"; and a concrete floor on Site 5 covered coins of Tetricus and Carausius and was laid down, therefore, not earlier than the end of the 3rd century. But these scraps of information do not materially advance our knowledge of the site, and the evidence hitherto obtained from the excavations is of value in bulk rather than in detail. The Roman cemeteries have not yet been identified. Two or three burials outside the E. gate have been noted above and may represent the fringe of a burial-ground. Within the walls, in the angle of a small building, a female skeleton was discovered in 1913, with bone pins, a bone button, and a coin of Carausius. Also within the town was found an urn, probably of 2nd-century date, carefully buried and containing burnt bones. Scattered burials such as these are not infrequently found in provincial Roman towns, where the Roman buriallaws were not always strictly observed, and are of no special historical significance.

Herefordshire, the Romano-British Town of Magna (Kenchester)

If we now review the meagre evidence as a whole, we find that it falls easily into place in the accepted scheme of Roman Britain. Magni was a small country town containing shops and dwellings built apparently in the conventional Roman manner, with occasional mosaic floors and abundant, brightly coloured wall-plaster. The streets were well metalled and well drained. The equipment of the citizens was almost entirely of mass-produced Roman type; only occasionally, as in a small bronze ox-head (Jack and Hayter, Excavations . . ., II, 24), is there a hint of native artistic expression. Whether or no the Roman town was a lineal descendant of the native hill-town of which the earthworks can still be seen on the neighbouring Credenhill, cannot at present be said. There is no evidence, such as has survived at Wroxeter, Caerwent and elsewhere, that Roman Magni represented politically a British tribal centre. We can only say, on the evidence of coins and pottery, that the life of the town began about the time of the emperor Vespasian (69–79 A.D.), whose coins begin the Roman series and whose general, Julius Frontinus, completed the subjugation of the neighbouring parts of Wales. When that life ceased is more difficult to say. The coins appear to end in or just after the reign of Gratian, who died in 383 A.D.; one indistinct coin only, of Arcadius or Theodosius or Valentinian II, may be as late as 392. A solitary small hoard of 51 coins found in a hypocaust in 1913 ends also with Gratian and slightly emphasises the terminal date. By the last quarter of the 4th-century, Romano-British country life was wellnigh extinct, and small country towns such as Magni can scarcely have survived long the de-Romanisation of the neighbouring countryside. A last memory of the place may indeed have lingered on into Saxon times. Mr. W. H. Stevenson has suggested (Jack and Hayter, Excavations . . ., I, p. 15 n.) that the name "Magonsetum," the oldest recorded form (811 A.D.) of the English Magesaetas, "who settled in Herefordshire and plainly took their name from some place," may enshroud the name of Magni. But the epitaph of the ancient city was written by Leland: "The place wher the town was ys al overgrowen with brambles, hasylles, and lyke shrubbes. ... Of the decay of Kenchestre, Herford rose and florishyd."

N.B.—The numbered sites on the accompanying plan refer to the full descriptions in Jack and Hayter's Excavations.

[See Victoria County History, Herefordshire, I, 175; and, especially, G. H. Jack and A. G. K. Hayter, Excavations on the Site of the Romano-British Town of Magna, Kenchester, pub. by the Woolhope Club, Hereford, 1916 and 1926; help also received independently from Mr. G. H. Jack, F.S.A.]

Ecclesiastical

a(2). Parish Church of St. Michael (Plate 8) stands in the N. W. angle of the parish. The walls are of local sandstone rubble with dressings of the same material; the roofs are slate-covered. The church, consisting of continuous Chancel and Nave, was built in the second half of the 12th century. The bell-cote is of the 13th century and the wall below is thickened as a support. The South Porch was added in the 15th century. The N. wall of the chancel was re-built at some uncertain date, perhaps when the roof was renewed in the 17th century. The church was restored in 1909 and again in 1925.

Architectural Description—The Chancel (13½ ft. by 16 ft.) has a late 13th-century E. window of three plain pointed lights in a two-centred head with a moulded label. In the N. wall is a 12th-century window of one round-headed light. In the S. wall is a similar window and farther W. are two voussoirs, perhaps part of the rear-arch of a second window, now destroyed. There is no chancel-arch.

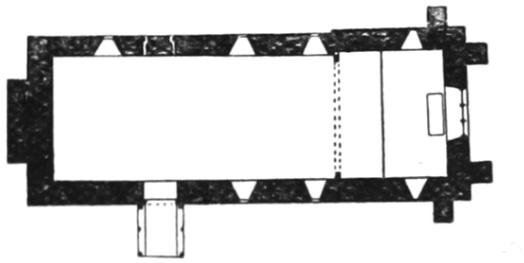

The Church, Plan

The Nave (35½ ft. by 15½ ft.) has, in the N. wall, three modern windows; the blocked N. doorway has chamfered jambs and segmental head; it is partly of the 12th century. In the S. wall are two modern windows; the 12th-century S. doorway has roll-moulded jambs and round head. The gable of the W. wall is pierced for a bell-cote of two pointed 13th-century openings under a pointed label; the wall below the openings is twice tabled out over a thickening of the wail, built either to support a former bell-cote carried up above the gable or simply to strengthen the existing wall itself.

The South Porch is timber-framed and probably of the 15th century, much restored. The outer entrance has curved braces below the tie-beam and intersecting diagonal struts above. There is also a truss against the nave-wall.

The Roof of the chancel (Plate 19) is of early 17th-century date and of two bays with as many trusses; these have curved braces below the collar meeting at a pierced and carved central pendant; above the collar is a central post with ornamental framing on either side of it. To the W. of the western truss is an earlier truss with sloping struts to the principal rafters; the moulded wall-posts are re-used material, and on the N. post (probably the former rood-beam) is a length of late 15th-century fascia carved with vine-scroll; below the tie-beam is modern framing incorporating a 17th-century pendant. The roof of the nave is ceiled but has five trusses with tie-beams and sloping struts; near the W. end is an additional tie-beam.

Fittings—Bells: two, uninscribed but of late date. Bracket: In chancel—on E. wall, plain with chamfered underside, mediæval. Door: In S. doorway—of nail-studded battens with ornamental strap-hinges, probably mediæval. Font: tall cylindrical bowl with tapered under edge and shallow basin, round stem and moulded base, perhaps re-used Roman material on 12th or 13th-century base. Monument and Floor-slabs. Monument: In chancel—on S. wall, to Francis Smyth, 1644, and Bridgett (Rogers) his wife, 1656, slate tablet. Floor-slabs: In chancel—(1) to N......, 1711; (2) name defaced, 1696–7. Painting: In nave—on splays of N. doorway traces of red and yellow colour. Piscina: In chancel—rectangular corbel with square drain, date uncertain.

Condition—Good.

Secular

a(3). Court Farm, house, 60 yards W. of the church, is of two storeys; the walls are of stone and the roofs are tiled. It was built early in the 17th century with a cross-wing at the S.W. end. There is an 18th-century extension on the N.E. Inside the building the ceiling beams are exposed.

Condition—Good.

a(4). Cottage, 400 yards E. of the church, is of two storeys, timber-framed and with slate-covered roofs. It was built probably early in the 18th century and has exposed external framing and internal ceiling-beams.

Condition—Good.

a(5). Cottage, on the N. side of the road, 650 yards S.E. of the church, is of two storeys, timber-framed and with a thatched roof. It was built in the 17th century. The external framing and the ceiling-beams are exposed.

Condition—Fairly good.

b(6). Old Weir, house, on the S. side of the road, 1 m. S.E. of the church, is of two storeys with attics; the walls are of timber-framing and brick and the roofs are slate-covered. The E. block was built early in the 17th century and extended N. later in the same century. There are large modern additions on the W. Inside the building are some original moulded ceiling-beams and two original panelled doors.

Condition—Good, much altered.

b(7). Stone-lined pool, or tank, on the bank of the Wye in the grounds of New Weir, nearly 1 m. S.S.E. of the church, is an octagonal stone construction, 5½ ft. across, consisting of four steps diminishing the width to about 1½ ft. In the middle is a round hole communicating with the channel of a stream below. There is no evidence of the date of the structure.

Condition—Good.