An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1985.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Hardingstone', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton(London, 1985), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol5/pp268-294 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Hardingstone', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton(London, 1985), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol5/pp268-294.

"Hardingstone". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 5, Archaeology and Churches in Northampton. (London, 1985), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol5/pp268-294.

In this section

9 HARDINGSTONE

(OS 1:10000 aSP 75 NW, bSP 76 NE)

The parish lies S. of Northampton and the R. Nene. Prior to various re-organisations of the 19th century, due to the encroachments of an expanding Northampton, the parish consisted of 1199 hectares, including 160 hectares which comprised the hamlets of Cotton End or East Cotton and Far Cotton or West Cotton. The two hamlets, lying on the S. side of the Nene immediately S. of Northampton, had been included in the liberties of the borough in 1618 for a short time, but soon reverted to Hardingstone parish (VCH Northamptonshire III, 31). Part of the ecclesiastical parish was assigned to Far Cotton in 1875 and the two hamlets were constituted the civil parish of Far Cotton in 1894. At the present time Hardingstone parish is split in two by Far Cotton parish. The pre-1894 boundaries are, however, used in this Inventory and thus some of the sites listed under Hardingstone are now in Far Cotton.

The old parish lay on the S. side of the Nene valley running from a boundary with Wootton at the crest of a ridge down to the R. Nene. To the E. its boundary with Great Houghton is marked for most of its length by a brook running N. into the Nene, while to the W. Wootton parish extends N. to form its boundary on this side.

Along the lower ground, near the river, there are extensive spreads of alluvium and gravel. To the S. are large areas of Upper Lias Clay which cover most of the parish, except on the higher ground over 90 m. above OD where Northampton Sands, silts, clays and limestones of the Estuarine Series and Great Oolite Limestone are exposed.

Hardingstone is first mentioned in Domesday Book while Cotes (i.e. Cotton) is first recorded in the 12th century. Cotton End owes its existence to the fact that it is situated at the main medieval crossing of the R. Nene to the S. of Northampton. Far Cotton is likely to have had an earlier origin for it lies at the point where the river was probably forded to enter the Saxon town of Northampton (Lee 1953, 166ff). Hardingstone village lies towards the E. of the parish at around 90 m. above OD, on the spring line, where the Upper Lias Clay meets the Northampton Sands.

The parish is rich in archaeological remains of the prehistoric and Roman periods, the most notable being the neolithic enclosure of Briar Hill (7) excavated in 1974–8, the Iron Age hill fort of Hunsbury (14) and the series of 1st-century Roman pottery kilns (4a, b, 15, 16).

Prehistoric and Roman

A number of palaeolithic implements found in 1906 and 1910 are recorded from Hardingstone, in addition to those from Hunsbury Hill (see below). They may have been discovered in the gravel pits in the N. of the parish (SP 767592) though this is not certain. They include a number of heavily rolled mid to late Acheulean hand axes and waste flakes (NM; NDC P114, 134).

A mammoth tusk has been discovered in gravel working at c. SP 760593 (NM; NDC P160). Part of a neolithic stone axe (Group XXIIIa) has been found on the S. side of Hardingstone village within the Roman settlement (4) (NM Records; private owner; NDC P250). Several worked flints were discovered in 1974 in Delapré Park (SP 757584–760584; Northamptonshire Archaeol 10 (1975), 151; NDC P116) and others were noted in 1965 in Hardingstone Lane at the W. end of the village (c. SP 759579; NM Records; NDC P202).

Roman coins, including a silver one of Nero (AD 54–68), were found before 1712 near Queen Eleanor's Cross (c. SP 754582; Morton 1712, 504; NDC R23). Other Roman coins are said to have been discovered during the removal of some 'tumuli' in Delapré Park before the mid 19th century (Wetton 1849, 137). No such tumuli are known, however, and although a slight mound still exists at SP 75525871 this appears to be natural. A coin of Maximian (AD 286–305) was found E. of the village in 1957 (SP 77555790; NM Records; NDC R94) and a dupondius was discovered near the Power Station in 1973 (c. SP 764598; NM; NDC R192).

Small quantities of Roman pottery, as well as some possible late Iron Age wares were found N.E. of the village in 1973 (c. SP 775584; NDC R126) and another small amount of Roman pottery is recorded from further S.E. (SP 784581; NDC R99).

b(1) Ring Ditches (c. SP 777586), lie N.E. of Hardingstone village, on glacial sand and gravel, at 60 m. above OD. Two ring ditches 30 m.-35 m. in diameter are visible on air photographs (in NMR) in an area of intense polygonal frost-wedging (NDC A36).

b(2) Enclosure (?) (c. SP 780579), lies E. of Hardingstone on Upper Lias Clay at 69 m. above OD. Air photographs (FSL 6565, 1851–2) show the cropmarks of a roughly D-shaped enclosure about 85 m. across (BNFAS 5 (1971), 40; NDC A9).

b(3) Ring Ditch (SP 77225738), lies E.S.E. of Hardingstone on Northampton Sands at 105 m. above OD. Air photographs (in NMR) show a ring ditch 25 m. in diameter and other vague circular and rectilinear features in the surrounding area which may be natural (BNFAS 6 (1971), 13; Northamptonshire Archaeol 15 (1980), 176; NDC A11).

b(4) Roman Settlement(s), Iron Age Enclosure lie under and around Hardingstone village on Northampton Sands, Estuarine Series deposits and Great Oolite Limestone, between 100 m. and 110 m. above OD. A large quantity of material has been recorded from the area of the village and may possibly represent a single large settlement and industrial complex although, alternatively, the remains may only witness more ephemeral and dispersed activity. The discoveries include the following:

(a) On the S. side of the village (c. SP 764574), four pottery kilns and a network of ditches and gullies containing pottery dating from the pre-Belgic Iron Age to the mid to late 1st century AD were excavated in 1967–8. The ditches of two sides of a rectangular enclosure, visible on air photographs (in NMR), were also sectioned. These revealed three phases of construction, the latest being dated to the first half of the 1st century AD (Woods 1969; BNFAS 2 (1967), 10–11; NDC A12, R15). An Iron Age coin (Potin Class II) was also discovered (Woods 1969, 38; Haselgrove 1978, 49). Roman pottery was found to the W. in 1973 (SP 761575; NDC P87, R108). More Roman pottery is recorded as having been found in 1957 (SP 76285746; NM Records; NDC R232).

(b) A little to the N.W. (c. SP 763576), another seven pottery kilns also dating from the 1st century AD were excavated in 1965 (BNFAS 1 (1966), 8–9). A series of ditches nearby were examined at a later date (NDC R16).

(c) On the E. side of the village (c. SP 770578), Roman pottery, including Nene Valley wares, and large quantities of animal bones, said to have been laid on a stone floor, were found during ironstone quarrying in 1853 (J Brit Archaeol Ass 10 (1855), 92; Botfield 1853, pl. 16; NDC R21). Roman pottery was found during field-walking nearby in 1973 (c. SP 769577; NDC R107).

(d) Roman pottery is recorded from 'a dump' in a garden in 1951 (SP 76225784; OS Record Cards; NM; NDC R24).

(e) Immediately to the S.E. of the village (c. SP 758576), air photographs (FSL 6565, 8148–50) show very indistinctly the cropmarks of a small sub-circular feature about 10 m. across and a larger circular enclosure some 50 m. in diameter (BNFAS 5 (1971), 40; NDC A10).

(f) Three coins, of Tacitus (AD 275–6) and Probus (AD 276–82), and perhaps more were found in an urn in 'Hardingstone Field' in 1845 (NPL, Dryden Papers). It has been suggested that this was a 'third brass' hoard of AD 250–80 (VCH Northamptonshire 1, 217). The exact find spot is unknown though local information places it on the N.W. side of the village (SP 760581; OS Record Cards; NDC R22).

(g) There is a vague reference to Roman coins and 'wooden coffin pins' being found in Hardingstone Lane (perhaps around SP 758579; White 1977, 4).

(h) Two Roman coins have been found in Bouverie Road in the centre of the village (SP 76635755; antoninianus of Philip 1 (AD 244–9); NDC R154. c. SP 763576; 'third brass' of Constans (AD 333–50); NDC R170) and another in The Warren on the E. side (SP 76705760; NDC R202).

b(5) Ditch (SP 782592), in the extreme N.E. of the parish, on gravel at 59 m. above OD. During building work on the new industrial estate part of a ditch, about 1.5 m. wide, was noted. A single sherd of Roman grey ware was recovered (Northamptonshire Archaeol 15 (1980), 167; NDC R165).

a(6–19) Hunsbury Complex (Fig. 3). The W. part of Hardingstone parish, bounded on the N. by the R. Nene, on the W. and S. by Wootton parish and on the E. by the Towcester Road (A43) is one of the richest archaeological areas in the county. This is the result of a number of factors. Its situation, in a region which also includes the major Roman settlement at Duston immediately to the N., as well as the medieval and modern town of Northampton to the N.E., suggests that the area has been for long a nodal point for settlement and communication. The immediate physical environment must have also been important and the N.-facing slope, between 112 m. and 60 m. above OD, mainly on light Northampton Sands, was undoubtedly suitable for early occupation. It is, however, the events of the last century which have led to the major discoveries and without them it is possible that the evidence for early occupation in the area would consist of little more than the small hill fort of Hunsbury at the top of the slope, although aerial photography has, as so often elsewhere, led to the identification of many sites. The large-scale ironstone quarrying which took place in the late 19th century, extending over some 40 hectares of land in and around the hill fort, coincided with an upsurge of local interest in the past, with the result that records, though inadequate, were made of discoveries and a large proportion of the objects found were collected and preserved, mainly in NM. More recent and even more extensive activity began in 1960 with the expansion of Northampton over this area. The development of extensive housing estates during the last 20 years, together with the work of the Archaeological Unit of Northampton Development Corporation, has led to the discovery and excavation to modern standards of a number of sites which otherwise would never have been recognised.

A very large number of prehistoric flint tools have been found at various times in the area of Hunsbury hill fort though the exact locations are not recorded. These include over 130 cores, microliths and flakes of mesolithic type (in NM) and another 50 or so cores, scrapers and flakes, generally of mesolithic to Bronze Age types (in PM) all listed as 'from the Hunsbury area'. Other mesolithic material, including microliths, found in 1904–12 on the N. side of Hunsbury Hill is noted (NM; VCH Northamptonshire I, 139; Wymer 1977, 216; NDC P142–3).

Neolithic type flints, including arrowheads and a small polished axehead are also recorded from the area (NM; NDC P141). At least some of this material may have come from the general area of the neolithic causewayed enclosure (7) though this cannot now be proved (Northamptonshire Archaeol 9 (1974), 84; NDC P66, 113). Further worked flints of neolithic and Bronze Age forms, perhaps from within or very close to the hill fort (SP 737583) are known (PM; NDC P140). In recent years further worked flints have been found during field-walking in the area. Some, together with a sherd of Roman pottery, were noted before 1971 (SP 735585; BNFAS 6 (1971), 13, Hardingstone (2); NDC R98) and more were discovered in the same area in 1973 and 1979 (NDC P178, 180). A small number of worked flints were recorded in 1973–5 well to the E.S.E. of Hunsbury Hill and close to the Wootton parish boundary (c. SP 744581; NDC P179, 185). Two small Bronze Age 'cups', 'from Hunsbury' are in NM.

A bone tool of unknown date has also been found near the hill fort (NDC P181) while a single Roman coin, a denarius of Valens (AD 364–78) was picked up in 1946 (SP 73945864; NM; NDC R18).

The enclosure alleged to be visible as cropmarks from the air S. of Hunsbury Hill Farm (BNFAS 7 (1972), 57; NDC A52) is in an area of intensive polygonal ice-wedging and may be natural.

a(6) Enclosure (c. SP 731586; Fig. 3), lies S.S.W. of Hunsbury Hill Farm, at the junction of Upper Lias Clay and Northampton Sands at 75 m. above OD. Cropmarks, described as an enclosure and 'fields', are said to be visible on air photographs though any archaeological cropmarks are difficult to distinguish from the periglacial marks in the same area (Northamptonshire Archaeol 12 (1977), 229; NDC A55).

a(7) Neolithic Causewayed Enclosure (SP 73625923; Figs. 1, 3), lies on Briar Hill 800 m. N. of Hunsbury hill fort, on Northampton Sands, at 75 m. to 80 m. above OD. The site was discovered during aerial survey in 1972 (Northamptonshire Archaeol 8 (1973), 26) and subsequently field-walking over the general area in 1973 led to the discovery of many worked flints, chiefly flakes but also some cores, scrapers and microliths. These were scattered over a broad zone (SP 73905900–73325932) but with two particular concentrations (SP 73415919 and 73865902; Northamptonshire Archaeol 9 (1974), 84; NM; NDC P113). Other flints had been found nearby on earlier occasions (SP 737589; BNFAS 4 (1970), 4; NDC P66) and some of the flints attributed to Hunsbury Hill (see above) also seem to have come from here.

Excavations on the enclosure were carried out by the NDC Archaeological Unit between 1974 and 1978, when approximately half the total area was investigated.

The neolithic enclosure, covering just over 3 hectares, was defined by two concentric interrupted ditch circuits 15 m.-20 m. apart and contained an elliptical inner enclosure formed by an in-turning extension of the inner ditch on the E. side. The main ditches were made up of short, steep-sided, flat-bottomed segments 3 m.–4 m. wide across the top and 1 m.-2 m. deep, but the ditch on the W. side of the inner enclosure included an arc of smaller pits less than 1 m. in depth. An asymmetrical pattern of infill in many segments of the outer ditch has been interpreted tentatively as evidence of the weathering and collapse of a steeply revetted internal bank, although no trace of this was discovered on the surface.

The enclosure seems to have been in use, though not occupied continuously, throughout much of the neolithic period. The ditches around both the outer and inner enclosures were found to have been redug several times, apparently at infrequent intervals, and half of the segments investigated contained evidence of between three and six successive cuts. A series of radio-carbon determinations for samples from the ditch fills suggests that the original construction of the site took place in the mid 4th millennium BC (3730 BC ± 70 (HAR - 4072); 3590 BC ± 140 (HAR - 4092); 3490 BC ± 110 (HAR - 2287)), and that the final recutting of the inner ditch circuit, at least, was not later than the mid 3rd millennium BC (2710 BC ± 70 (HAR - 4057); 2660 BC ± 90 (HAR - 4071); 2650 BC ± 90 (HAR - 3208)).

Finds were concentrated particularly in segments of the ditch around the inner enclosure, especially on the W. side, and included sherds of neolithic bowls, worked flints, fragments of stone axes (Groups I, VI, VII and XX), saucer querns, rubbing stones, and grinding or polishing stones.

Several features of neolithic date were found in the inner enclosure, and most if not all of these post-date the final reconstruction of the earthworks. Charcoal from one of a number of small pits has been dated 2420 BC ± 80 (HAR - 4074), and from two pits 26 m. apart which may have been footings for massive posts there are dates of 2340 BC ± 80 (HAR - 2625) and 2300 BC ± 70 (HAR - 4057). One of the most interesting features of all was the foundation slot of a small but substantial sub-rectangular wooden structure, and this contained sherds of grooved ware and charcoal dated 2060 BC ± 90 (HAR - 2607).

Other evidence of the use of the site during the later neolithic period included sherds of Mortlake and Fengate style impressed ware and Beaker pottery found in the final silt of the ditches, and several pits, producing radio-carbon determinations ranging from 1840 BC ± 100 (HAR - 4073) to 1590 BC ± 80 (HAR - 2389), which had been dug into these final infill layers.

A small group of Bronze Age cremation burials was discovered on the S.W. side of the outer enclosure, 9 m. inside the inner edge of the inner ditch. This comprised a cluster of shallow pits, at least 10 of which contained surviving cremation deposits. Four of these were in badly decayed, bucket-shaped urns, one being radio-carbon dated 1230 BC ± 70 (HAR - 4065). Of the remainder, one, which gave a date of 1750 BC ± 150 (HAR - 4058), was accompanied by a flint barbed-and-tanged arrowhead (Bamford 1976; 1979; Wilson 1975, 180–1, pl. XIX; Northamptonshire Archaeol 12 (1977), 209; 13 (1978), 179; CBA Group 9 Newsletter 4 (1974), 22; 6 (1976), 33–5; 7 (1977), 8; NDC P76A).

a(8) Pit Alignment (SP 73635932–73705931; Fig. 3), found during excavation of (7). Part of a pit alignment running E.-W. was discovered on the N. side of the Neolithic enclosure and a length of 112 m. excavated. No internal dating evidence was found but it was cut by pits of Roman date and is thus of Iron Age or earlier date. It runs parallel to and 300 m. S. of a similar alignment (11). (Bamford 1976, 10; 1979, 6; NDC P76B).

a(9) Iron Age Settlement (SP 73655920–73545924; Fig. 3), found during the excavation of (7). Three rectangular enclosures and a number of associated pits, all containing Iron Age pottery, overlay the neolithic enclosure. Two of these enclosures lay side by side in the S.E. part of the site. The larger, 30 m. by 21 m., was surrounded by a ditch of V profile, 1 m. deep, and the other, 15 m., by 11 m. by a slot 0.3 m.-0.4 m. deep for a fence or palisade. Both had entrances on the E. side, and to the N. and E. of them was a loose cluster of pits. The third enclosure, 11 m. by 11 m., with a ditch 0.6 m.-0.7 m. deep, was some distance away on the W. side of the site. Pits immediately to the W. and S. of it contained slag and fired clay (Bamford 1976, 10; 1979, 6; NDC P76C).

a(10) Iron Age Enclosure (SP 73785897; Fig. 3; Plate 1), lies 500 m. N. of Hunsbury hill fort, on Northampton Sands, at 90 m. above OD. An almost square double-ditched enclosure with an entrance in the centre of the S.E. side of the inner ditch is visible on air photographs (CUAP, BCP45–6; BNFAS 6 (1971), 13; Northamptonshire Archaeol 8 (1973), 26). Trial excavations by NDC Archaeological Unit in 1973 revealed that the ditches were about 4 m. wide and 2 m. deep, but no archaeological features were visible in a trench cut across the interior. A small quantity of Iron Age pottery was recovered (Northamptonshire Archaeol 9 (1974), 115; NDC A29, P60).

a(11) Pit Alignment (SP 73955902–74125900; Fig. 3), N.N.E. of (8) on Northampton Sands at 82 m. above OD, was excavated in 1969 during housing development (Jackson 1974, 13–32). It was traced for almost 170 m. running E.-W. Two phases were recognised, the earlier consisting of a double row of small pits 0.75 m.-1.25 m. across and 0.25 m.-1 m. deep. This was replaced by larger rectangular pits 2.5 m.-3.25 m. by 2 m.-2.25 m. across and 0.75 m.-1.25 m. deep. Weathered sherds, probably of early Iron Age date, were recovered from the fills as well as some worked flints, two scrapers and two arrowheads (NDC P107).

a(12) Iron Age Settlement (SP 739591; Fig. 3), 160 m. N. of (11) on Northampton Sands, at 80 m. above OD, was discovered in 1969 during housing development. Three pits and a shallow ditch containing Iron Age pottery were excavated (Jackson 1974, 23, 26–7; NDC P186). Further pits containing worked flints and Iron Age pottery were discovered in 1975 immediately to the E. (SP 73935918; NDC P18).

a(13) Iron Age Ditch (?) (SP 73365852; Fig. 3), lies E. of (6), on Northampton Sands, at 100 m. above OD. A short linear feature visible as a cropmark on air photographs (in NMR) was exposed during road works. It was about 1 m. wide and two sherds of Iron Age pottery were found in the fill (Northamptonshire Archaeol 15 (1980), 166; NDC P149). Ring ditches and (?) ditches are reported from nearby (c. SP 733587) on further air photographs (Northamptonshire Archaeol 15 (1980), 176; NDC A72).

a(14) Hill Fort (SP 738583; Figs. 3, 4; Plate 2), usually known as Hunsbury stands on the summit of a rounded but prominent hill, on Northampton Sands, at 110 m. above OD. The surrounding land slopes only gently in all directions, but the position affords extensive views over Northampton and the whole of the upper Nene Valley to the N., N.E. and N.W. as well as to the S. and E.

Most of the interior of the fort and much of the surrounding land was quarried for ironstone in the late 19th century and, as a result, a vast amount of archaeological material was recovered, making Hunsbury one of the richest Iron Age sites in the British Isles. This quarrying, as well as perhaps earlier cultivation, has so altered the defences as to make it difficult to ascertain their original form.

1. Defences

The fort now consists of a roughly elliptical area, 1.6 ha. in area, bounded by an inner rampart and central ditch and with an outer rampart on the N.W., N. and N.E. sides. Almost the same picture is recorded by Morton (1712, 537) and by Bridges (1791 1, 358). It is possible that there was an outer ditch, and one is mentioned as having been found 'in the external ironstone diggings' in an account of 1891 (Baker 1891–2, 66), though whether this was an external ditch to the fort is not clear; other lengths of ditch were discovered early in this century to the N.W. and S.W. of the fort, about 90 yards from the inner ditch (George 1915–18, 3; OS 2½ in. map, 1901 edn.). On an air photograph (in NMR) are vague cropmarks just outside the fort on its S.E. unquarried side. These may represent an outer system of ditches. Elsewhere, if they ever existed, they have been entirely removed by ironstone quarrying.

The inner rampart is the largest of the remaining defences and is now a steep-sided feature with a markedly narrow summit, usually less than 0.5 m. across. It rises to a height of 3.7 m. above the interior and 4.5 m. above the ditch. These dimensions taken from the present shape of this rampart are, however, unlikely to bear any relationship to the original form. Except on the E. the rear of the rampart has been cut away by the ironstone quarrying in the interior which has not only produced the steep-sided appearance but, as the land there is up to 2 m. lower than it was prior to quarrying, has also made it appear much higher. The original form is also obscured by what appears to be a small hedge bank on top of the rampart in places. On the S.E. side, where the quarrying did not take place and where, therefore, the original internal land surface still remains, the internal rampart hardly exists at all. The present low scarp is partly a hedge bank and partly a negative lynchet produced by modern and perhaps ancient cultivation of the interior.

The central ditch remains intact around almost the entire circuit of the fort. As a result of the external and internal quarrying it is difficult to ascertain its exact depth below the natural ground surface but it is probable that it was about 2 m. deep. A number of low banks and scarps crossed the bottom of the ditch on the E. and N.E.(?) and there is a small pit just N. of the S.E. entrance. No date or purpose can be assigned to these.

Immediately N.E. of the N.W. entrance the ditch has been partly filled by later material for a distance of about 30 m. To the S. of the same entrance the ditch appears to be blocked completely by later spoil in two places, so that the inner and outer ramparts have the form of a single broad-topped feature with a large hole in the centre. However, traces of the outer rampart's inner edge still just survive, showing that the material is a later dump. This material, as well as that in the ditch bottom to the N., can be assigned to the period of ironstone quarrying (see below under Entrances).

The outer rampart does not survive on the S.W. and S., having been probably destroyed by the old drift-way which follows the parish boundary between Hardingstone and Wootton. On the E. only a low bank 0.5 m. high remains and this is perhaps in part an old hedge bank. The original rampart may have been destroyed by or for cultivation. On the N.E., N. and N.W. this outer rampart still exists 2 m.-2.5 m. above the bottom of the ditch inside it. The outer face of this rampart has, however, been largely cut away by ironstone quarrying. The result of this is that although the rampart is now up to 4 m. high above the present ground surface in the N.W. this is at least 2 m. below the original land surface. Indeed, the lower part of the apparent rampart is a near vertical face of undisturbed ironstone, marking the edge of the old quarry. This rampart, like the inner one, is now much higher and steeper than it was originally.

The defences have been sectioned three times. The first was in 1880 when a tramway access was cut through the N.W. side. Dryden (1885–6, 55) made drawings and a brief note on the exposed faces but these only indicate that the ditch was of U-shape and had been cut to a depth of just over 3 m. into the underlying ironstone and that the inner rampart stood just under 3 m. above the external ground surface.

The other sections were cut in 1952 by R.J.C. Atkinson as part of a small excavation on the site. The results have not been published in full and the following account is based on notes made on a lecture given by Atkinson in 1968 (in NM Records). Two trenches were cut across the inner rampart and ditch on the N.E. and the S.E. sides at the points where the outer rampart no longer survives. The N.E. cutting revealed that the ditch had originally been about 8 m. deep and that the rampart behind it was timber-laced. The S.E. cutting was more informative, showing that the original ditch had been recut and the timber-laced rampart had been converted into one of glacis construction. This later rampart had been extended over the back of the earlier one and overlay a pit and a post-hole which were not excavated. This evidence has been used to suggest that there was originally an undefended settlement on the site (Fell 1953, 213) but it is clear that the evidence of settlement - the pit and post-hole - only predates the second phase of the rampart, not the first. Two orientated skeletons buried in the second phase of the rampart were discovered but no evidence of date was recovered.

2. Entrances

There are now three entrances through the ramparts and the same number certainly existed before the ironstone quarrying commenced. It is no longer possible to be certain whether any of these are original. Dryden, who saw the site during the quarrying process thought that the N. entrance was not original but that the other two were. One apparent reason for this opinion was that he thought that the old drift-way once passed through the fort and that it was later diverted round it to the S. (Dryden 1885–6, 54).

The S.E. entrance may be original. The adjoining ditches terminate against the sloping causeway in cusped ends and there is certainly no sign of later alterations. The N.W. entrance is very different. It is a straight cut through the ramparts with its surface level with the quarry floors both inside and outside the fort and with vertical faces of ironstone visible in the ends of the ramparts. This indicates that it was used during the quarrying phase as a tramway access point. There is, however, good evidence that this entrance actually dates from the period of quarrying. Dryden, as noted above, while describing three entrances as existing before the quarrying commenced, also says that 'about 1880 . . . an entrance was made in the north west into the camp about 70 feet to the north of the old entrance'. This figure of 70 ft. (21.3 m.) is important for it shows that the older entrance lay at a point where the ramparts are now joined together by a large amount of later spoil. It seems likely that this earlier entrance was completely blocked in 1880 and a new entrance cut a few metres to the N. (see RCHM Northamptonshire II, 92, Irchester (7), for similar example of the blocking of an existing entrance to the defences of the Roman town).

The N. entrance is also a straight cut with ironstone rock exposed in the ends of the ramparts and with low banks blocking the ditch termination. The width (3.5 m.), parallel sides and level surface suggest that, though perhaps an older entrance, it was re-cut to take a tramway during the ironstone quarrying. Nevertheless, the fact that the original ground inside and outside the fort at this point is 0.25 m. below the surface of this entrance suggests that it had been abandoned before the quarrying was completed.

3. The Interior

Within the defences the original land surface probably sloped gently down from the S.E. to the N.W. The ironstone quarrying altered this situation completely for the work commenced to the S. of the new entrance and 'digging nearly up to the edge of the scarp . . . gradually wheeled round to the north, working from the entrance as a pivot' (Dryden 1885–6, 55). Between 3 m. and 5 m. of material was removed in the operation but, because the ironstone ran out towards the S.E., a small area in the S.E. corner of the interior was left unquarried. Today most of the land within the defences is uneven but the unquarried section is still visible in the S.E., its W. edge marked by a long scarp up to 2 m. high. In view of the discoveries made during the quarrying this fragment of the undisturbed interior is of considerable archaeological importance.

During the period of quarrying between 1883 and 1886 the work was closely watched by Sir Henry Dryden, who attempted to keep together the many finds and who drew plans and sections and published a detailed account (Dryden 1885–6). A later account by the Rev. R.S. Baker (1891–2, 53–7), though chiefly concerned with 'proving' that Hunsbury was a Roman frontier fort, acts as a useful supplement to Dryden. Within the interior, Dryden noted that there were over 300 pits of which six or seven were stone-lined. They were closely packed together and varied from 2 m. to 2.5 m. deep and 1.75 m. to 3.25 m. across with 'nearly perpendicular sides'. They were apparently filled with dark soil or 'black mould' though charred grain is recorded from some. Most of the numerous finds seem to have come from the pits.

4. Finds from Interior of Fort

There is a very large collection of material (in NM) 'from Hunsbury'. Most of it certainly came from the interior of the fort but some was recovered from the area around it during the ironstone quarrying there. Such material as can reasonably be assigned to the exterior of the fort is described separately (see below and fiche p. 273) but some of it cannot be located with certainty and is listed here. Other material has been found later both within and outside the fort and is included in the appropriate section. The bulk of these finds have not been studied in depth and the whole collection is in need of detailed examination before any conclusions can be drawn.

Considerable amounts of pottery survive, including some fine examples of globular bowls with the distinctive 'Hunsbury curvilinear' decoration. Although the presence of vessels decorated with applied cordons, extensive finger-tipping and incised geometric decoration may indicate activity on the site prior to the later (La Tène) Iron Age, the bulk of the pottery probably dates to no earlier than the 5th century BC. In view of the very small quantity of 'early' material, and its very wide date range, it seems more reasonable to regard it as broadly contemporary with the later Iron Age pottery from the site rather than as indicative of a substantial phase of pre-La Tène occupation. The absence of Belgic material is, in an area with a high density of Belgic sites, also probably of some chronological significance. The earliest Belgic wares in this region appear from the later 1st century BC, and the Hunsbury pottery may, therefore, predate the final decades of the 1st century BC, certainly c. AD 25 at latest (pers. comm. D. Knight for most of above).

The other finds from the fort may be broadly grouped into industrial or craft objects, including nails, iron knives, axes, adzes, sickles, saws, chisels, bill hooks, plough-shares, spindle whorls, whetstones, querns and bone weaving combs, as well as iron slag and pottery crucibles for bronze working; military objects, including iron swords, bronze and iron scabbards (notably the 'Hunsbury Scabbard'), daggers, spearheads, and shield bosses; decorative objects including bronze fibulae, pins, tweezers, rings, belt-links, bracelets and glass beads; and objects attesting to the use of horses including bronze terrets and rings, iron bridle bits, horn cheek-pieces and the iron tyre of a chariot wheel. Baker (1891–2, 71) states that the skeletons of a man and a horse were found together, along with a bridle bit and pieces of iron tyre and other metal objects. A quantity of iron currency bars, a bronze spoon, bone gaming pieces, bones of cattle, sheep/goats, horses, pigs and dogs as well as of humans also survive. Flint objects include waste flakes and barbed-and-tanged arrowheads. Roman pottery, mainly Nene Valley Ware, has also been found within the fort though apparently only one late Roman coin. (For Saxon finds see below).

5. Finds from Exterior of Fort

It is not possible to say where the bulk of the material from Hunsbury was found and some of it was probably discovered outside the defences. Baker (1891–2, 70) suggests that skeletons, accompanied by scabbards and shield bosses were found just outside the W. entrance though Dryden (1885–6, 57–8), while including these discoveries in his report, does not mention any location or association of these objects. Dryden does, however, state that five human skulls were found to the N.W. of the fort and worked flints have been found in the area immediately N. of the fort (see also introduction above).

Works of reference discussing Hunsbury and its associated finds are many and only a few can be listed here. They include: Morton 1712, 537–8; Bridges 1791 1, 358; Dryden 1885–6; Reid 1890; Baker 1891–2; Pitt-Rivers 1892, 286–7; Smith 1912; George 1915–18; Fox 1927, passim; Dunning 1934; Fell 1936; Curwen 1941, 16–22; Philips 1950; Piggot 1950, 5–12; Fell 1951; Tylecote 1962, 347; Allen 1967, passim; Manning 1972, passim; Proc Soc Antiq II (1885–7), 175; 12 (1887–9), 321; 20 (1903–5), 184–5; 27 (1914–5), 74; 30 (1917–8), 56–7; VCH Northamptonshire I, 147–53; Antiquity 5 (1931), 82; 14 (1940), 432; Archaeol J 104 (1947), 89; Proc Prehist Soc 26 (1960), 172; Northamptonshire Archaeol 11 (1976), 163–5; RAF VAP CPE/UK/1994 1181–2; V58–RAF-1122, 0332–4; CUAP HF-54).

a(15) Roman Kilns (c. SP 738585; Fig. 3), found in 1875 during ironstone quarrying, 100 m. N. of Hunsbury hill fort, on Northampton Sands, at 104 m. above OD. Two circles of 'clay props' each about 1.25 m. in diameter where discovered together with at least one fire bar and some Roman pottery (Dryden 1885–6, 61; VCH Northamptonshire I, 217). Such kilns are likely to be of 1st to 2nd-century date (Woods 1979). A coin of Claudius Gothicus (AD 268–70) was also found (NDC R19, 157).

a(16) Roman Settlement and Kilns (SP 73555884; Fig. 3), found by the NDC Archaeological Unit and excavated during housing development in 1978–9, lay 400 m. N.N.W. of Hunsbury hill fort on Northampton Sands at 100 m. above OD. Three mid 1st-century pottery kilns were recovered as well as another possible kiln or oven of the late 1st to 2nd century. In addition a large number of features including ditches, pits, a piece of limestone walling and robbed-out wall trenches were found over an area of some 2 hectares suggesting a Roman settlement of the late 1st to early 2nd century AD, though, as a result of the circumstances of excavation, no overall plan was recovered (Shaw 1979; NDC R153).

a(17) Roman Settlement (SP 734588; Fig. 3), found by NDC Archaeological Unit during road construction in 1976, lay 150 m. W. of (16) on Northampton Sands at 100 m. above OD. Ditches and pits containing 1st-century pottery were discovered (NDC P85).

a(18) Roman Settlement (?), Kiln Material (SP 74485883), lay to the E. of the railway, 800 m. N.E. of Hunsbury hill fort on Northampton Sands at 82 m. above OD. During ironstone quarrying in 1884 a stone-lined well 0.5 m. in diameter and 3.5 m. deep was discovered. Near the bottom were five pots, probably of Nene Valley type, cattle bones and fragments of wood. The same quarry also produced five kiln bars (Dryden 1885–6, 61; NDC R20). A coin of Victorinus (AD 269–71) was found in the same area in 1966 (NM).

a(19) Roman Settlement (?) (SP 73665932; Fig. 3), probably existed to the N.E. of (7). During excavation of the latter, a group of irregular pits containing 1st-century and later pottery and a shallow gully running N.W.-S.E. were discovered on its N. side, overlying the outer ditch of the Neolithic enclosure and on the edge of the excavated area (Bamford 1976, 10; 1979, 7; NDC P76D).

Medieval and Later

A Saxon spearhead (in NM) was found in 1956 in Bouverie Road, Hardingstone village (c. SP 765575; Northampton Chronicle and Echo, 2 March 1956; NDC AS16). A large St. Neots ware cooking pot was recovered from somewhere in Cotton End (c. SP 750595; Kennett 1968, 9; NM; NDC M84).

Small quantities of medieval pottery have been recovered from several locations in the parish (SP 76385986; NM; NDC M72. c. SP 759577; NDC M119. c. SP 764581; NDC M174. c. SP 775584; NDC M437). Late medieval pottery is also recorded from one place (c. SP 744581; NDC M185).

A silver penny of Alexander III of Scotland (1249–85) has been discovered on the W. edge of the village (SP 75975792; NM; NDC M296). A bronze ring, probably originally with enamel decoration, is recorded from somewhere in the parish (lost; Wetton 1849, 139). A decorated tile is recorded from the Delapré area (c. SP 759590; NM; NDC M313).

b(20) Parish Church of St. Edmund (SP 763578; fiche Fig. 29; Plate 28)

Development

The earliest part of the fabric appears to be the tower, of c. 1200. The nave and narrow aisles probably date from the 13th century although no fabric of that period remains. In the 14th century the arcades were replaced, the N. and S. porches added, and the belfry heightened. In the post-medieval period, clearstorey windows were inserted and the S. chapel added. The chancel was rebuilt in the mid 18th century, probably c. 1764. The aisles were refenestrated with Gothic windows, in place of classical, in 1846. The church was restored in 1868–9 by R. Palgrave. The 18th-century fittings were removed, new roofs framed and new E. and W. windows inserted. (VCH Northamptonshire IV, 256–8).

History

A mid 12th-century origin has been suggested (Franklin 1982, 119f) but the church is first mentioned in Henry I's confirmatory grant of 1107 to St. Andrew's Priory, Northampton (Davis et al 1913–69 II, no. 833). Hardingstone appears in the late 12th century to have been divided between royal demesne and a member of the comital estate whose caput was at Yardley Hastings. Grants from both were made to St. Andrew's in the early 12th century but it seems possible from Hardingstone's inclusion in the deanery of Northampton that it was originally part of the parochia of St. Peter's, Northampton and one of the many churches once ruled by Bruningas from there (Franklin 1982, 80, 115, 242–3). The vicarage endowment perhaps instituted by St. Hugh, listed in the Liber Antiquus (Gibbons 1888, 33), and the small glebe of one virgate there mentioned supports the inference of an origin as a dependent chapel of St. Peter's.

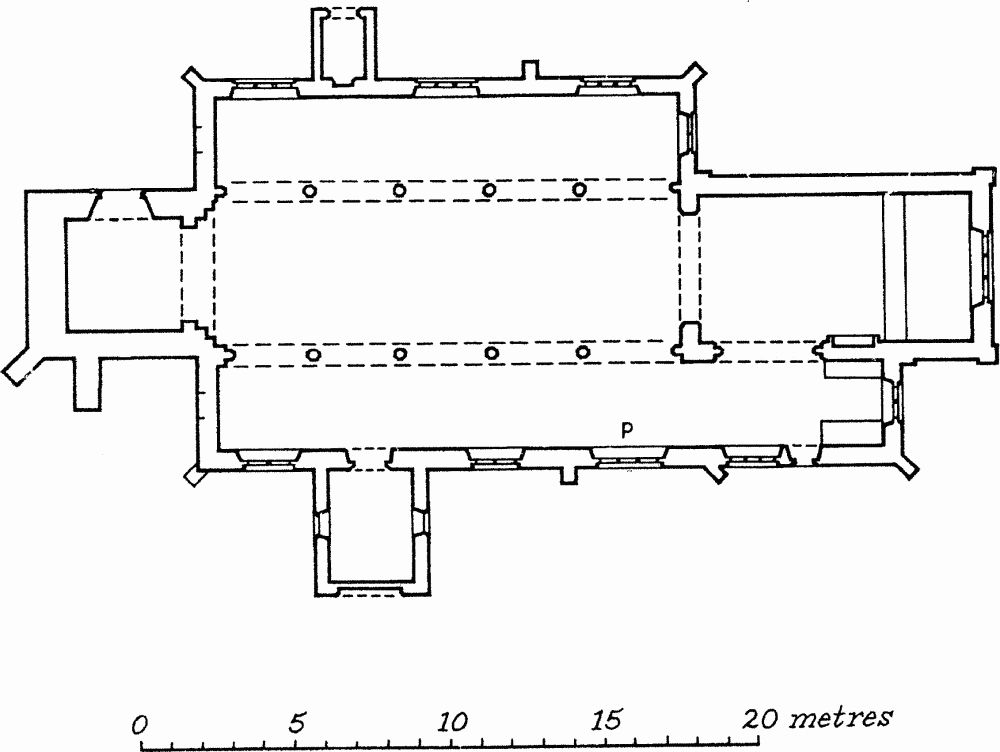

Fig. 29 Parish Church of St. Edmund. Outline plan.

Description

The church consists of a Chancel, South Chancel Chapel, Nave, North and South Aisles, North and South Porches (the former now blocked off from the nave and the latter now a vestry) and a West Tower.

Chancel

The chancel was rebuilt c. 1764 and re-Gothicised in the 19th century. The angles are quoined and the parapet interrupted by pedestals, giving the impression of battlements. The N. wall is featureless except for a fine monument of c. 1746 by Rysbrack. A classical round-headed E. window was replaced by the present Gothic window in 1868. In the S. wall is a re-assembled tomb recess of the late 16th century, with a tomb chest and a three-centred arch carried on pilasters which have lost their capitals. The angel of the Last Trump appears at the apex. To the W. is an arch into the S. chancel chapel. The arch is of two orders, the outer continuous, the inner on polygonal half-shafts with moulded capitals of four uniform rolls, perhaps of c. 1600. A hood mould was added in the 19th century. The roof is of 1868.

South Chancel Chapel

The chapel was added to the aisle in the post-medieval period, probably c. 1600. The original corner of the S. aisle with its buttress is still visible although the aisle plinth was continued on the new work. The straight-headed two-light E. window has cinquefoil-headed lights, the cusping probably added in the 19th century; the masonry of the external face of the E. wall is very disturbed. The S. window is similar to the E. window but of three lights. The S. doorway has a four-centred head and wave mouldings. The roof of the chapel is of 1868.

Nave

The N. arcade is of five bays, with double-chamfered arches carried on octagonal piers. The moulded capitals of the piers are all similar except that the capital of the easternmost pier is less tall than the others. The three square clearstorey windows are post-medieval. The chancel arch is of two chamfered orders, the outer continuous, the inner carried on polygonal corbels. The corbels and the hood moulds of the arch are certainly 19th-century and the whole arch may be a 19th-century re-fashioning of a Georgian predecessor. The S. arcade is similar to the N. except that the westernmost pier and arch are of grey limestone, unlike the ironstone of the rest. The clearstorey is the same as on the N. The tower arch is offset to the S. by 200 mm. The arch is of three unchamfered orders with a two-centred head. The chamfered impost moulding is very simple. The nave roof is 1868.

North Aisle

The aisle is united by continuous mouldings at sill and ground level, which include the buttresses. In the N. wall are three straight-headed Perpendicular three-light windows of 1846, which have splayed jambs and flat lintels internally rather than rear-arches. The blocked N. doorway is continuously moulded and has a two-centred head. The E. window is similar to those in the N. wall and is an insertion of 1846. The W. wall is now blind but a blocked single-light window is visible externally. The roof is 19th-century.

South Aisle

The plinth of the aisle is continuous with that of the S. porch. The three windows in the S. aisle have the same detailing and are of the same date as those in the N. wall. Under the easternmost window is a piscina with a two-centred head, cusped into a trefoil. (The external face of the S. doorway was inaccessible). As with the N. aisle, the W. wall is blind but has a blocked single-light window visible externally. The aisle roof is of 1846.

North Porch

The plinth includes the mouldings of the outer N. doorway, which is continuously moulded and has a two-centred head. The plaster vault inside the porch is half-ruined.

South Porch

The S. porch has trefoil-headed windows in the E. and W. walls, perhaps of the 19th century. The blocked outer S. doorway has a depressed four-centred head, of c. 1600, which was probably inserted over the jambs of a 14th-century opening. Within the porch is a groined plaster vault.

West Tower

The tower is built of oolitic rubble as far as the middle of the belfry stage; the rest of the tower and the belfry openings are of ironstone. The tower rises in two stages with no set-backs. It is unbuttressed except for the added buttressing at the S.W. angle and on the S. wall. The N. doorway is a reworking of 1868 of an apparently 18th-century doorway shown in a drawing by G. Clarke. An earlier blocked doorway is visible to the E. of it. The belfry openings are of two trefoil-headed lights. The tower is crowned by a post-medieval parapet with obelisks at the corners.

a(21) Saxon Settlement (SP 736592; Fig. 3), was discovered during the excavation of (8). Up to four sunken-featured huts were located, all sub-rectangular, between 3 m. and 5 m. long by 2 m.-3 m. wide, and dug 0.4 m. into the subsoil. One had a post-hole at each end and contained large quantities of pottery, perhaps 6th-century in date, animal bones, two iron knives, part of a quern, two lead loom weights and a bronze bracelet. The others contained small quantities of similar pottery and a glass bead. A slot or palisade trench nearby may have been associated with these features (Bamford 1976, 10; NDC P76E).

a(22) Saxon Settlement (?) (c. SP 738583; Fig. 3), within Hunsbury hill fort. A number of finds of Saxon date have been recovered from the interior of the fort which suggests that it may have been occupied in Saxon times. A recent re-examination of the pottery from the site, chiefly found during the ironstone quarrying of the 1880's, has led to the identification of about 100 sherds of early to middle Saxon date though possibly only a few vessels are represented (BNFAS 7 (1972), 41; Medieval Archaeol 16 (1972), 158–9). A spindle whorl and a loom weight are probably also of this date. A silver sceatta (Series B type, AD 575–775) was found in the N. part of the fort in 1956 (Metcalf 1976, 1–2). Two human skeletons were discovered in 1952 during excavations through the S.E. rampart. They were orientated and had been cut through the material of the second phase of the Iron Age defences (Fell 1953, 213; Meaney 1964, 189). A 'cinerary urn' containing glass and amber beads and a crystal spindle whorl, found at 'Hunsbury', was given to the Society of Antiquaries in 1779 (by 'Pownell F.S.A.', Minutes XII, 493) while a crystal ball cut into facets is also recorded as coming from 'Hunsbury' (Akerman 1855, 39). T.J. George recorded the discovery of 'some Saxon pots a few hundred yards from Hunsbury (letter to E.T. Leeds, Ashmolean Museum; NDC P51).

(23) Saxon Cemetery (unlocated), apparently found in 1855 somewhere in the parish. There is no evidence that the material came from Hunsbury, as has been claimed, and it may have been associated with (24) below or be a separate site. The size of the cemetery is uncertain but it would seem to have contained at least several burials for Bateman records 'evidence of Pagan rites attending some of the interments coupled with the Christian character of the relics accompanying others, point out a time when the customs of heathendom were slowly giving way to the influence of Chritianity; and which may be probably fixed about the close of the seventh century.' The nature of the so-called Christian relics is unknown; what survives (in NM) are two iron spearheads, a bronze horse-bit and a bronze garnet-studded disc mount (Bateman 1860–1, 189–90; Meaney 1964, 189; VCH Northamptonshire I, 253; NDC AS4).

b(24) Saxon Burials (SP 764574), found in 1967–8 on the S. side of the village during the excavation of (4a). Three inhumation burials, two with associated grave goods which included iron kinves, an iron buckle, a necklace and a silver pendant were discovered. The burials are dated to the mid 7th century. (Inf. P.J. Woods; NDC AS23)

b(25) Site of DelaprÉ Abbey (SP 75965906), lies I km. N. of the village, on the edge of the floodplain of the R. Nene, on glacial sands and gravels, at 60 m. above OD. The site is that of a house of Cluniac nuns, founded by Simon de Senlis II, Earl of Northampton, in about 1145. Little is known of its history but it was never a large prosperous establishment and in 1530 only 11 nuns are recorded. It was finally dissolved in 1538 and by 1548 the site had been bought by the Tate family who owned it until the mid 18th century when it was sold to the Bouveries. This family held it until 1946.

Though the existing building shows the changing tastes of its post-medieval owners, its plan still retains the basic form of the aisleless church and its claustral range to the S. The analysis of these structures is beyond the scope of this volume and the only archaeological finds are those of medieval burials. At least one stone coffin and apparently other burials and/or coffins were discovered in the early 17th century during extensive rebuilding on the site of what had been the nuns' choir. One of these was re-discovered nearby in 1940 and reburied. Two other stone coffins containing skeletons were discovered in 1895 during the laying of a new drainage system in the grounds and though the exact location is not known it is likely that they were found to the E. or S.E. of the church, that is around the N.E. corner of the existing building. (VCH Northamptonshire II, 114–5; Serjeantson 1909a; Knowles and Hadcock 1971, 270; Northamptonshire Past and Present 2 (1958), 225–41; Pevsner 1973, 252–3; Northampton Herald 15 June 1895; NPL, Dryden Collection; NDC M21).

(26) Site of Chapel of St Thomas (c. SP 75465973), on the S. side of the S. bridge, near Cotton End. A St. Thomas' Chapel is first mentioned in the late 12th century when it was confirmed to St. Andrew's Priory (Mon Angl 5, 191) but this may be the chapel of St. Thomas recorded within the precinct of St. Andrew's Priory at this time (BL Royal 11 B ix f. 131a). In a will of 1527 a chapel of St. Thomas is identified as the hermitage at the S. end of the South Bridge. The 'Armitage' was still in existence in 1602 (Goodfellow 1980, 141; NDC M41).

a(27) Site of Hospital of St. Leonard (SP 75525956), in Cotton End, on alluvium, at 59 m. above OD, immediately S. of the R. Nene on the E. side of the main road S. from Northampton. It was founded in about 1150 as a leper hospital and included a chapel and a graveyard which acquired semi-parochial rights for the inhabitants of the adjacent hamlet of East Cotton. At least one building survived until 1823. Some time in the late 19th century skeletons were dug up in the area and further remains were discovered in excavations for a new LMS railway workshop in 1946. These were presumably from the hospital graveyard. (VCH Northamptonshire III, 60; IV, 256; Serjeantson, 1915–16; Northampton Chronicle and Echo 17 Oct. 1946; NPL, Dryden Collection; NDC M31).

(28) Settlement Remains (SP 76785791), in the N.E. of the village, at the N.E. end of The Green, on Northampton Sands at 99 m. above OD. During building work on an empty plot what was interpreted as a medieval pit, containing a single sherd of 14th-century pottery and sealed by a post-medieval yard and later out-buildings, was discovered (Northamptonshire Archaeol 15 (1980), 172; NDC M286). Though of little archaeological interest, these discoveries point to the need for further work on the village in order to understand its possible origins as a poly-focal settlement, with two separate field systems (see (30)). Documentary evidence and topographical considerations indicate that the village had two distinct parts: a complex arrangement of lanes in the N.E. centred on The Green, and a long single street to the W. with the parish church on its S. side (Hall, 1980).

b(29) Hollow-Way (SP 765589), runs N. for 200 m. from the W. end of Back Lane, Hardingstone village. It is up to 20 m. wide and 2 m. deep and is the S. end of an old road leading towards the E. gate of Northampton which crossed the R. Nene at Nun Mills (SP 76165996). This route is mentioned in a charter of c. 1200 (NRO, NBR, Private Charters II; NDC M320).

(30) Cultivation Remains. The common fields of Hardingstone were enclosed by an Act of Parliament of 1765 (NRO, Enclosure Map 1767). Recent work on the medieval fields of the parish has shown that there were two separate field systems in existence at least as early as 1583 and probably by about 1220 (Hall 1980). Each of these field systems appears to have been associated with a separate part of the village thus indicating that the village was poly-focal in origin (see (28)).

The W. part of the parish was occupied by the West End field system, made up of Mere, Moor, Radwell (alias Grange), Long Haukway and Long Bromhill Fields, while in the E. part lay the East End field system comprising the Upper (alias Preston Hedge), Middle, Moor and Firedale Fields.

Ridge-and-furrow of these fields exists on the ground or can be traced on air photographs over large parts of the old parish. In the W., a number of rectangular furlongs with ridges running down-slope were formerly visible (c. SP 730585) and further fragmentary remains once existed N. of Briar Hill Farm (c. SP 742593). To the E. and S. all traces of ridge-and-furrow are lost, as a result of ironstone quarries around Hunsbury and the 19th-century and later development of West and East Cotton. Large areas of ridge-and-furrow still exist in Delapré Park (centred SP 756586) where it is arranged in interlocked rectangular furlongs, many of reversed-S. form.

In the E. end of the parish almost the entire pattern of ridge-and-furrow is visible on air photographs, though much has now been obliterated by recent industrial developments. There was formerly a particularly well-defined area of ridge-and-furrow, consisting of rows of end-on furlongs separated by massive sinuous headlands up to 1 km. long.

The detailed examination of this ridge-and-furrow, together with documentary research, has indicated a number of features of considerable interest (Hall 1980). In at least two places the surviving ridge-and-turrow is orientated at right-angles to the strips listed in a 1660 terrier. No trace of the earlier orientations is visible, but the evidence indicates that these furlongs were re-ploughed in an entirely different direction, sometime after 1660.

More important is the discovery that in 1660 the strip holdings were still arranged in a regular pattern of a 32–cycle, whereby each tenant had the same strip in each cycle. This pattern is close to the medieval Swedish solskifte system and probably reflects the way that the strips were initially laid out. It further appears that the 1660 furlongs post-date this arrangement and that originally there were massive blocks of strips which were subsequently divided into smaller furlongs. (RAF VAP CPE/UK/1994, 1179–87, 1249–55, 3173–7; V58–RAF-1122, 0273–88, 0300–17, 0329–46, 0359–77; FSL 6565, 1844–52)