An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1984.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface: Ecclesiastical Architecture', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire( London, 1984), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/lxxii-ciii [accessed 27 July 2024].

'Sectional Preface: Ecclesiastical Architecture', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire( London, 1984), British History Online, accessed July 27, 2024, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/lxxii-ciii.

"Sectional Preface: Ecclesiastical Architecture". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the County of Northamptonshire, Volume 6, Architectural Monuments in North Northamptonshire. (London, 1984), , British History Online. Web. 27 July 2024. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/northants/vol6/lxxii-ciii.

In this section

ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE

This Inventory is limited to twenty-four parishes, and therefore the following discussion is based on a small number of churches. A forthcoming volume, devoted entirely to ecclesiastical monuments in Northamptonshire, will, however, allow a review of these buildings in a wider context.

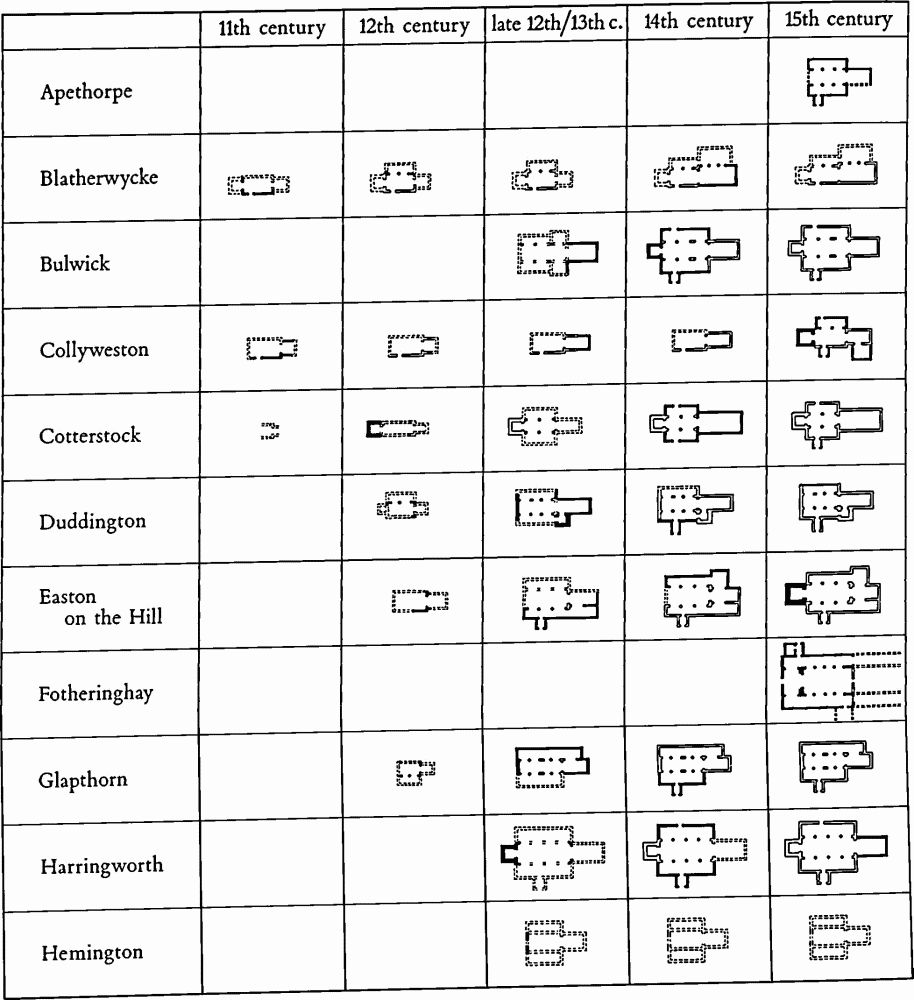

No excavation has been carried out in the churches of the area and thus this Preface takes the form of a chronological analysis of the standing remains, most of which date from the Middle Ages. Particular attention is paid to the development of the plans and cross-sections of the churches; Fig. 9 has been included to illustrate the former on a comparative basis, and to chart something of the rise and fall of building activity throughout the Middle Ages. The diagram also shows the extent of the survival of building from one period to another, and demonstrates the range of plans used during the medieval period. Furniture and fittings are considered selectively and only those which provide evidence for the development and change in use of the churches in which they are found are discussed in this Preface. The remainder are described in the Inventory and listed in the Index.

All twenty-four parishes have parish churches with the exception of Fineshade, where there is no church, and Ashton which is a chapelry of Oundle. The parish churches of Blatherwycke and Wakerley are Redundant. There are five Non-Conformist chapels in use and two more in ruins, all of which date from before 1850. There are also six chapels of later date. A room at the rear of 2 Bridge Street, King's Cliffe (6) was formerly used as a Roman Catholic chapel.

During the Middle Ages there were considerably more ecclesiastical institutions and the remains of three have been identified. At Harringworth (2) there are the remains of a small chapel, and at Cotterstock and Fotheringhay parts of collegiate buildings survive. Those listed below are known from documentary record and earthwork remains but do not survive as buildings above ground level.

The Augustinian Priory of St. Mary at Fineshade was founded by Richard Engayne, who died in 1208, and was dissolved in 1536 (Knowles and Hadcock, 140). No trace now remains of the Priory but it probably lay near the site of the house which was demolished in 1956 (Fineshade (1)) (RCHM, Northants. I, Fineshade (3)).

The parish of St. Mary Magdalene at Blatherwycke was united with the parish of Holy Trinity in 1448 (LAO, Reg. 18 Bp. Alnwick f.20, Blatherwycke). The reasons for the amalgamation were given as the scarcity of land for cultivation and the poverty of the parishioners. Services were to be celebrated on the feast day of St. Mary Magdalene in that church, but parishioners were absolved from the obligation to repair it, except for the enclosure of the churchyard. When the church fell into ruins the materials were to be used for the upkeep of the churchyard wall or for the repair of Holy Trinity Church. The church of St. Mary Magdalene was probably sited at the W. end of the present village where burials have been found (RCHM, Northants. I, Blatherwycke (3)).

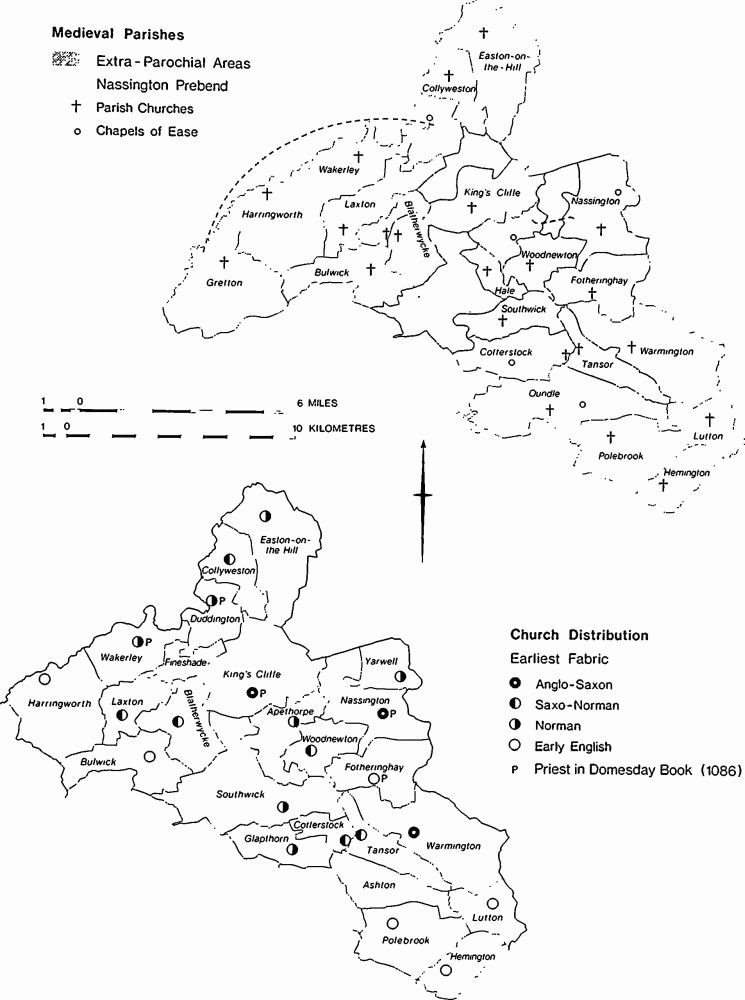

Fig. 8 Maps showing the medieval parishes and the distribution of churches surviving within the Inventory area

There was a parish church at Hale dedicated to St. Nicholas. The village was abandoned at the time of the Black Death (LAO, Reg. Burghersh f. 529; RCHM, Northants. I, Apethorpe (4)). The site of the church is unknown but earthwork remains of the village were noted in 1947 near Cheeseman's Farm in the S. part of what is now Apethorpe parish; all traces have now gone.

Two hospitals are known to have existed, at Armston in the parish of Polebrook and at Perio in the parish of Southwick. It is probable that the Hospital of St. John the Baptist at Armston was the chapel founded by Ralph de Trublevill and Alice his wife in 1232. It was dissolved in 1540 (RCHM, Northants. I, Polebrook (5); Knowles and Hadcock, 313; VCH, Northants. III, 105). The Hospital of St. John and St. Martin at Perio was founded in 1282. It was granted to Cotterstock College in 1338, and had stopped functioning as a hospital by 1535 when it was styled a free chapel. There are some earthwork remains of the settlement, but the site of the hospital is unknown (RCHM, Northants. I, Southwick (13); Knowles and Hadcock, 330).

A number of chapels is also recorded. The Chapel of St. Anne and Our Lady was in the churchyard at Bulwick. This was a perpetual chantry with two priests, founded by Geoffrey Cappe in 1357 for the king, Henry Duke of Lancaster, John of Gaunt and Sir William la Zouche of Harringworth. It appears that this chantry, originally within the church, was established in a separate building in the churchyard by 1373 (LAO, Reg. Gynwell 9, Bulwick Chantry f.226; Reg. Buckingham vol. 10 f. 192v, 16 June 1373). A Chapel of Ease is recorded at Elmington in 1189 (VCH, Northants. III, 99), but its location is unknown (RCHM, Northants. I, Ashton (5)). A chapel dedicated to St. Leonard is said to have been founded at Armston in the 13th century but it may well have been a part of the hospital. There were also a number of domestic chapels associated with the larger houses in the area; they are discussed under Secular Buildings.

Evidence For Church Distribution and Location (Fig. 8)

The remains of pre-Conquest churches within the survey area are slight. Building work survives at Nassington, which was a royal vill at the time of Canute (VCH, Northants. II, 587). The church was of some size and elaboration and probably dates from the early 11th century. No other early fabric can be identified but both King's Cliffe and Warmington appear to have plans of Anglo-Saxon form. The earliest identifiable work at King's Cliffe is of the 12th century, but the cruciform plan around a central tower with projecting angles is of the pre-Conquest form defined as a 'regular crossing' by H. M. Taylor who gives parallels at Norton (County Durham) and Stow (Lincolnshire), both dating from the late 10th and early 11th centuries. The long narrow outline of the nave at Warmington is very similar to that of Nassington, and a fragment of the triangular rear arch of a small window survives in the W. wall of the N. aisle.

The survey area lies between Stamford and Oundle, and the churches at King's Cliffe, Nassington and Warmington form a group approximately mid-way between the two. There was a monastic church at Oundle in the early 8th century when Wilfrid died there (B. Colgrave and R. A. B. Mynors, eds., Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Oxford Medieval Texts (1969), 528), and Stamford was well established in the 9th century (RCHM, Stamford) and is likely to have been a centre of ecclesiastical activity. King's Cliffe and Nassington lie within a late Saxon royal estate which can be identified from the Domesday Book (Fig. 4), and the cruciform plan of King's Cliffe church has been associated with later pre-Conquest minster churches (C. A. Ralegh Radford, 'Pre-Conquest Minster Churches', Arch. J., CXXX (1973), 131 ff.). Both these churches were large, as was Warmington, and all three appear to be of late Saxon date. Priests are recorded in Domesday Book at both King's Cliffe and Nassington, and also at Duddington, Fotheringhay and Wakerley.

A more detailed picture may be gained of the post-Conquest distribution (Fig. 8). Churches at Blatherwycke, Collyweston, Cotterstock, Laxton, Tansor and Woodnewton display work of the late 11th and early 12th century. Early in the 12th century Henry I endowed the prebend of Nassington with the churches of Southwick, Tansor, Woodnewton and Nassington, with its chapels of Apethorpe and Yarwell (LRS, 27, (1931), 30–1), all from within the area of the late Saxon royal estate. By the end of the century all the churches within the survey area, except for Lutton and Hemington, are known to have existed either from documentary sources or by physical survival, and by the mid 13th century the complete pattern can be seen. This has remained unchanged to the present day, but is now threatened by the redundancy of churches and by the reduction in the number of clergy.

Pre-Conquest

Only Nassington church has work that can certainly be assigned to the Anglo-Saxon period; this consists of a W. tower or porch which predates a large, probably aisleless, nave. The tower or porch was of at least three storeys, a room at the first floor had a double-splayed window looking down into the nave, and the room above had a doorway which must have given access to a gallery or upper floor at the W. end of the nave. The inner wall surface consists of rubble and nothing remains to suggest the function of these rooms. The position of the upper door indicates that the nave was very tall (Plate 2) and to judge from the size of the surviving W. wall it is probable that the nave was of the same length as the present compartment; much of the N. and S. walls may therefore survive from the Saxon period. A late 10th or early 11th-century date for this work has been suggested by H. M. Taylor (Taylor I, 455). There are also indications of late Saxon churches at both King's Cliffe and Warmington (see Church Distribution). Because of the late date of both these buildings they are considered under the category of Saxo-Norman remains.

Saxo-Norman

This work is distinguished by a mixture of simple late Saxon and primitive Norman features and is therefore difficult to date with any precision. Work can be identified at Blatherwycke, Collyweston, Cotterstock, King's Cliffe, Laxton, Tansor and Woodnewton, and belongs to the 11th and early 12th centuries. It is tabulated in column (1) of Fig. 9 with the slightly earlier Anglo-Saxon fabric. At Laxton the evidence is confined to the S. doorway which has primitive volute capitals. Herringbone masonry enables a nave width to be defined at Cotterstock and three sides of a W. tower at Tansor. At Blatherwycke much of the E. wall of the W. tower (Fig. 32) and the S. wall of the nave survives. The single-order tower arch is built of very large voussoirs and the impost has a pseudo-classical moulding, which approximates to a cyma. Centrally, above the tower arch, is a double-splayed window with radiating voussoirs which must have given a view E. from a first-floor compartment. Higher up again is an opening, now in the belfry, which incorporates the reused jambs of a small early Norman doorway with volute capitals (Plate 5). The head of the opening and the surrounding wall are all of post-medieval date. This was probably an external door, wider than at present, which was moved up when the tower was rebuilt, perhaps in the 17th century. The S. doorway is also of early Norman character (Plate 14) and has similar volute capitals. The walls where exposed are built of rubble composed of fairly large blocks and it is probable that all this work is of the late 11th century.

Fig. 9 Table showing comparative development of church plans

At Collyweston there are no datable architectural features, but a very unusual fabric of large irregular blocks with levelling courses defines the outline of the nave and chancel (Figs. 42, 43). One jamb of a window survives in the chancel wall, and the nave and chancel plinths are preserved in part. Distinctive though this work is there is little to indicate its date, but it will be seen that the plan forms of the naves of Blatherwycke and Collyweston are the same and that they match those of other naves, some of which are more clearly of Norman date. This group will be discussed below.

The early work at Woodnewton consists of an arch in the N. wall of the S. transept and the remnant of the triangular rear arch of a blocked window in the S. aisle. A church with at least a chancel, transverse chapel, nave and S. aisle is indicated. The semicircular arch to the transept (Plate 3) is like that at Blatherwycke and has capitals and bases with similar pseudo-classical mouldings, and may date from the later 11th century. The latest work in this group is the central tower of King's Cliffe. Although no fabric of the tower can be assigned to the Saxon period the irregular plan at ground and first-floor levels, and the protruding corners are both characteristic of Saxon work (Figs. 115, 116). The lower part of the tower is now obscured by plaster except for the surviving external projecting corner at the S.E. which is built with uniform rectangular quoins of hard shelly limestone. The upper part of the tower has a double-chamfered string course which forms the front edge of the sill of four openings of similar width, each central in its side. The openings on the E., N. and S. are all of similar design and are clearly windows, but that on the W. is different. It is of a single order and has two wider semicircular openings separated by two shafts supporting a through-stone abacus. It is suggested that this opening may have housed bells. Below the E. window is a small contemporary window which gave a view E. into the chancel from an upper room. Both the internal and external faces of the tower are built of coursed, rough blockwork, and probably date from the early 12th century.

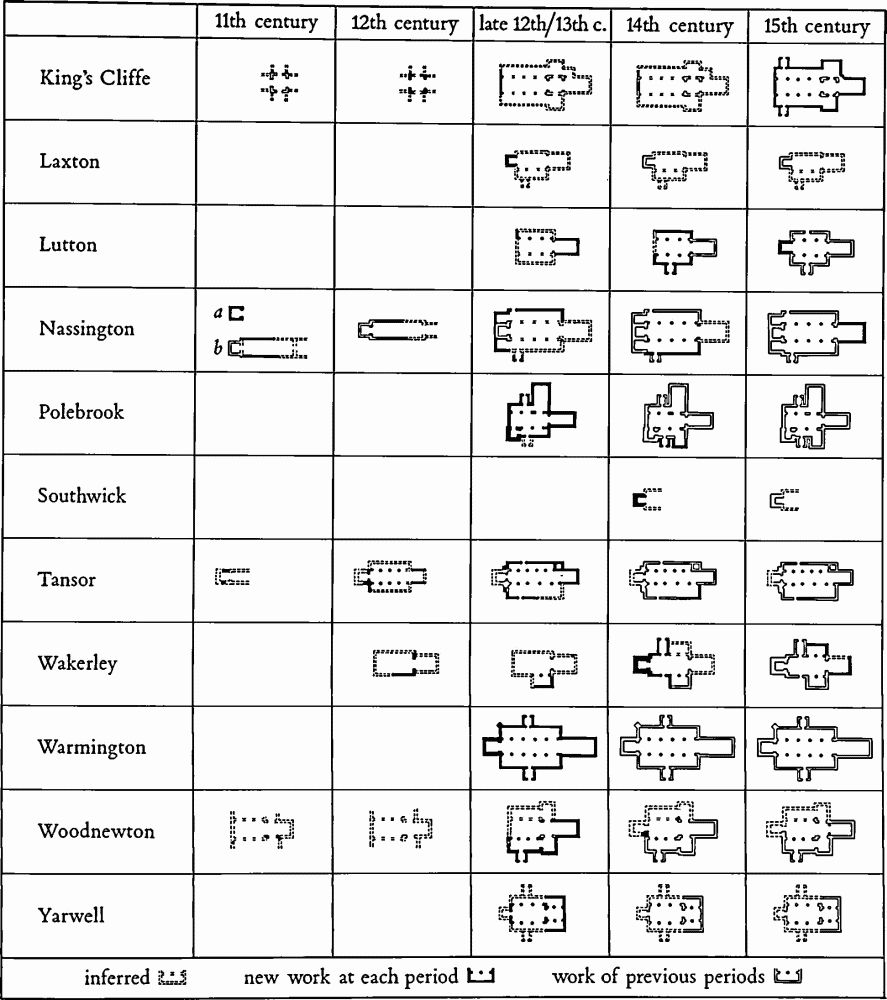

The available evidence gives a very fragmentary view of Saxo-Norman building in the area, but it is clear that there are some common elements of style and form. Perhaps the most consistent is that the towers at Nassington, Blatherwycke and King's Cliffe all had upper compartments from which an interior view of the church could be obtained, presumably to allow the main altar to be seen. This tradition seems to carry on into the 12th century as demonstrated at Tansor and perhaps Cotterstock. The earliest buildings in this group, King's Cliffe, and Nassington, have plans which are unmistakably pre-Conquest. Other buildings where evidence of plan form still exists, at Blatherwycke, Collyweston and Woodnewton, appear to have a plan type which persists until the late 12th century and this may be the clearest indication that they belong to the post-Conquest period (Fig. 10).

Norman

Fabric included under this heading is confined to that with clearly recognizable Norman characteristics. It is tabulated in column (2) of Fig. 9, and consists of work at Blatherwycke, Cotterstock, Duddington, Easton-on-the-Hill, Glapthorn, Nassington, Tansor and Wakerley, and has a date range from c. 1125 to c. 1190. The stylistic evidence consists of a number of well known forms ranging from cushion capitals and chevron ornament at Wakerley to scalloped capitals and billet ornament at Tansor. The full range is described in the Inventory. The outstanding work of this period is at Wakerley where the size of the building, the arrangement of the E. wall of the nave (Fig. 195) and the quality of the carved decoration throughout are remarkable (Plates 10, 11). The carving of the main capitals of the chancel arch has been compared by Professor Zarnecki with the work at Castor and a similar date of 1125 to 1130 suggested. The more abstract carving of the smaller capitals may be compared with the work at St. Peter's, Northampton.

Fig. 10 Norman naves of double-square proportion. Group 1 demonstrable. Group 2 inferred. Dimensions in metres.

The outlines of three naves at this period can be traced at Duddington, Glapthorn and Tansor. The first two of these and the earlier naves at Collyweston and Blatherwycke, though different in size, are all of the same proportion in plan which conforms to a double-square (Fig. 10, Group 1). The long dimension runs from the E. side of the chancel arch to the internal face of the W. wall of the nave and the short dimension is the internal width. As the double-square does not conform precisely with either the external or the internal measurements of the nave it is suggested that it was not merely an aid to setting out, but that it was a device for working out the interior space of the nave including that under the chancel arch. The double-square also clearly defines a division between nave and chancel on the E. side of the chancel arch. In this form of building the chancel arch is always within the E. wall of the nave and the chancel has only three structural walls. This line between nave and chancel, coincident in both structure and planning, may shed some light on the exact division of responsibility for maintenance of the church at this early date, later known to have been divided between parish and rector. Only at Collyweston is there an identifiable contemporary chancel but this is only a fragment and thus the dimensional relationship between nave and chancel is not recoverable. However, it is clear that this chancel was short, and narrower than the nave, and also that the outer faces of the side walls of the chancel were in line with the inner faces of the side walls of the nave. One further factor is an entrance on the S. towards the W. end found in the naves at Collyweston, Blatherwycke, Duddington and Easton-on-the-Hill.

Among this combined group of Saxo-Norman and Norman churches it is possible, therefore, to recognize the following characteristics of plan form:

A. A double-square system of proportion for the nave.

B. An entrance position towards the W. end of the S. side of the nave.

C. A relationship between the side walls of the nave and the chancel. (The inner faces of the walls of the nave line through with the outer faces of the walls of the chancel.)

D Short chancels.

(This factor is common to most churches of the period.)

Applying these characteristics to buildings without extensive identifiable work of the period it is possible to add three, or perhaps four, more churches to the group (Fig. 10, Group 2). Wakerley church has a double-square nave (A) and the nave and chancel wall relationship (C). Although the W. end of the nave was entirely rebuilt in the 14th century, the abnormally thick W. wall probably incorporates part of the Norman W. wall. There is now no trace of a Norman doorway in the nave because of re-building. This same combination of factors, nave proportion (A) and nave and chancel wall relationship (C), also applies at Woodnewton and provides a simple explanation for the plan and suggests the position of an early chancel arch. The single factor of the nave and chancel wall relationship (C) suggests that the W. ends of the N. and S. walls of the chancel at Easton-on-the-Hill are of Norman origin and perhaps contemporary with the S. wall of the nave. The door position in the S. aisle may suggest that this Norman nave was of double-square proportion, but the Norman W. wall has been lost. There is one other church, at Yarwell, which on the basis of nave and chancel wall relationship (C) and the short length of the chancel (D) may belong to this group, but it appears to have no fabric earlier than the 13th century.

To summarise, seven churches with identifiable work of the late 11th and 12th centuries exhibit one or more of the characteristics listed above (Fig. 10).

| Blatherwycke | A | B | ||

| Collyweston | A | B | C | D |

| Duddington | A | B | ||

| Easton-on-the-Hill | B | C | ||

| Glapthorn | A | |||

| Wakerley | A | C | ||

| Woodnewton | A | C | ||

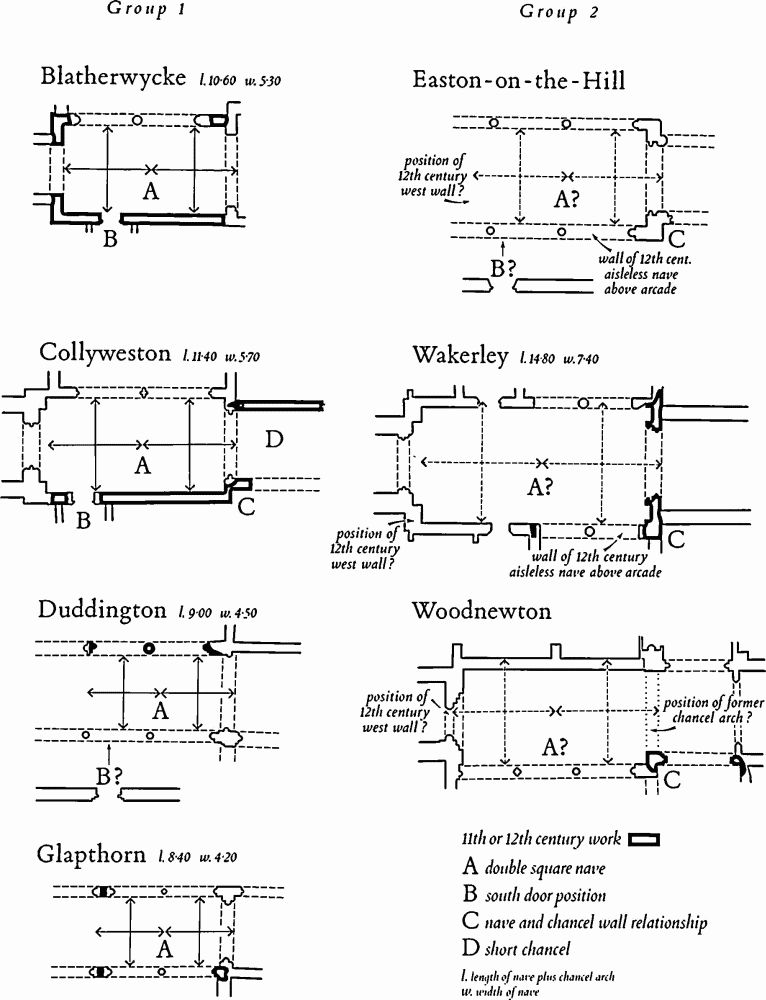

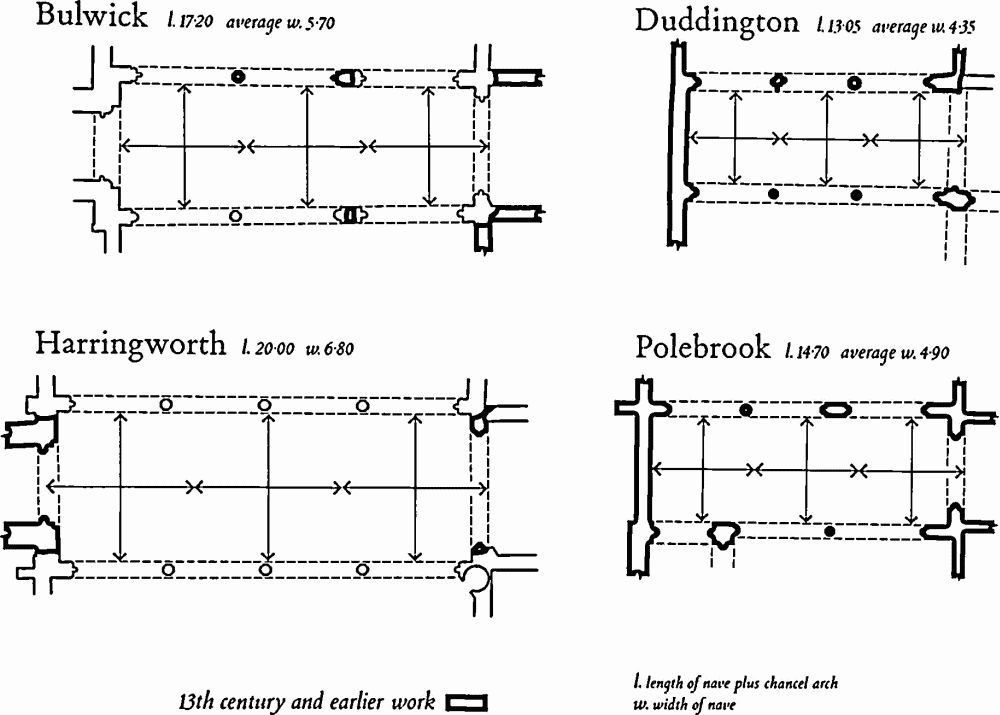

Fig. 11 Naves possibly of Norman origin

It may be possible to add three more churches, Harringworth, Lutton and Polebrook, to the list of those with Norman origins although like Yarwell, they appear to have no fabric earlier than the late 12th or early 13th century and to have a plan form typical of the Gothic period (Fig. 11). The position of entrance doors in the aisles at a point more or less central along the length of the nave, suggests that these churches once had a Norman double-square nave with an entrance at the W. end of the side wall (B). This observation is supported by the fact that when no earlier influence on planning existed, as at Apethorpe and Fotheringhay, which were entirely rebuilt in the 15th century, the main entrances were again placed at the W. end of the nave.

It is not possible to determine precisely what were the basic plan forms of these churches because of later alteration, but it is clear that by the mid 12th century most were more complicated than the simple two-cell form defined by Sir Alfred Clapham as the 'two-apartment type' (English Romanesque Architecture after the Conquest (1934), p. 104). Indeed Woodnewton appears to have had at least an aisle and transeptal chapel as early as the late 11th century. Clapham also makes a distinction between this type of Norman plan and the pre-Conquest plans of similar type which have naves of narrower proportion, as at Nassington, and perhaps Warmington. He further states that the simple nave and chancel type comprise the vast majority of early Norman churches, an observation confirmed in the area under study where most of these churches had naves with a double-square proportion (A).

A notable exception to this plan type occurs at Tansor, which was rebuilt, except for the W. tower, in the mid 12th century. The nave and chancel walls were built in line, the nave with arcades of four bays, and the chancel with semicircular-headed windows or blind arcading at a high level (Plate 12). The division between nave and chancel is now obscured by rebuilding, but is probably marked by a change in floor level. It is likely that there was no chancel arch and that the nave and chancel were roofed at the same level. A similar plan type occurs at St. Peter's, Northampton, at St. Mary in Castro, Leicester, and at All Saints, Laughton-en-le-Morthen, Yorkshire. The W. tower was converted to house a large first-floor gallery or pew with a wide semicircular-headed opening looking down the nave to the main altar, and an ample stair in a rectangular turret was constructed to serve it (Fig. 188). This uncommon plan and the upper compartment which dominated the W. end of the church suggest that this rebuilding was initiated by a person of some importance, possibly Hascuil de St. James who held five and a third hides in Tansor in the mid 12th century (VCH, Northants, I, 362–3). The other churches of this type are close to Norman castles which might indicate that they too were associated with people of importance. This unified plan form, which is more reminiscent of a choir and sanctuary of a conventual church than the nave and chancel of a parish church, may have been devised to combine the functions of private chapel and parish church.

There is a large variation in size within the group of naves which conform to a double-square proportion, the smallest being at Glapthorn (length 8.2 m., width 4.1 m.) and the largest at Wakerley (length 14.8 m., width 7.4 m.). A further impression of 12th-century naves can be gained from surviving features which illustrate their shape in cross section. The 12th-century eaves course of the S. wall of the nave at Wakerley is preserved indicating a wall height of 6.5 m., and the line of a matching roof with a pitch of about forty-five degrees is outlined by a weathering on the E. face of the later tower. The line of the 12th-century nave roof is also preserved at Tansor on the E. face of the tower. This also indicates a pitch of about forty-five degrees and suggests an eaves height for the nave similar to that at Wakerley (Figs. 188, 195). The nave width at Tansor is, however, only 4.2 m., scarcely more than half that at Wakerley. There are indications of 12th-century aisle widths at Duddington (1.9 m.) and Tansor (2.0 m.) but both have been rebuilt.

Very little exterior detail of 12th-century work survives. The tower at Cotterstock appears to have been unbuttressed and of rather squat proportions. The sole surviving stair, at Tansor, is built on a rough concrete spiral barrel vault and has discontinuous stone treads with a central newel. The stair is generous with a tread-width of 650 mm., and it rises to the first-floor room.

All churches of this period appear to have been built with rubble walls of local limestone, the size of blocks used being perhaps a little larger than in later work. Quoins, dressings, and decorative work are in better quality limestone, some of which is the hard shelly type associated with the quarries at Barnack. The only exception is at Collyweston where the earliest walls are quite distinct. They are built of very large roughly shaped blocks of limestone with a fair face, interspersed with narrow wedge-shaped levelling courses (Fig. 42).

No fittings or furniture survive from this period except perhaps for a plain piscina at Tansor which has been reset. Evidence for secondary altars survives at Wakerley, where they were against the E. wall of the aisleless nave flanking the chancel arch (Fig. 195). The only other evidence for use is plan form which suggests that the congregation were never far from the chancel arch and, assuming a short chancel, they must therefore have been aware of the detail of worship.

Fig. 12 Thirteenth-century naves of three-square proportion. Dimensions in metres

Thirteenth Century

The period of rebuilding which began in the late 12th century left hardly a church untouched. Nearly all were expanded, and new plans and cross sections were developed. Chancels were made longer and in some cases wider, naves lengthened, and aisles were an almost universal feature exhibiting great variation in width. Tall rectangular towers were built and crowned with broach spires. So fundamental and extensive was this programme of expansion that the naves and chancels of many churches reached a plan size which was never subsequently increased. This work is tabulated in Fig. 9, column 3. The early part of this period is also remarkable for the widespread retention of the semicircular arch, for doors, archways and arcades. It was often used in combination with pronounced Early English detail and mouldings.

The naves of these churches had small clearstoreys or none at all (Fig. 172) and were lit mainly from low aisles. In exceptional circumstances there was a W. window, as at Duddington and Polebrook where there were no western towers, but even so naves must have been dark in contrast to chancels which had high walls and were directly lit.

The great innovation of the later 13th century in this area was the building of a fully developed clearstorey at Warmington, which, in combination with a wooden quadripartite vault and flat-pitched aisle roofs, transformed the volume of the body of the church and dramatically increased the level of lighting from the side and above (Fig. 202). The external appearance was also completely altered. Other churches in the area, however, have modest clearstoreys which mostly date from later in the medieval period.

The architectural development of Warmington church which took place throughout the 13th century is outstanding. The reason for this is not altogether clear, but the advowson was held, probably from the beginning, by Peterborough Abbey. Warmington was an outstandingly rich living; when churches in this area were assessed under the Taxatio Ecclesiastica of Pope Nicholas IV in c. 1291, the average valuation of a parish was £11.8s. 5d. whereas Warmington was assessed at £36.13s.4d. (M. J. Franklin, Northamptonshire Past and Present VI, No. 4, p. 197).

Enlargement of Churches

Enough evidence of earlier work remains at Collyweston, Duddington and Glapthorn to demonstrate in detail some of the ways in which Norman churches with double-square naves were enlarged. The simplest example is at Collyweston where the nave remained intact and only the chancel was extended. At Glapthorn the nave was extended to double its internal length, and the chancel was rebuilt, presumably wider and longer than the one it replaced. There were also N. and S. aisles and a N. chapel at this time. Duddington presents a more complex picture but the evidence is remarkably complete. The double-square nave was extended W. to give a plan with a proportion of three squares including the chancel arch. This was achieved by the addition of one square bay and probably displaced a W. tower, which was resited in the angle between the S. aisle and the chancel because of falling ground at the W. The earlier entrance position on the S. side of the nave appears to have been retained although the nave was by this time aisled on both sides. The chancel was rebuilt presumably wider and a great deal longer than its predecessor.

The remaining ten 13th-century naves which survive wholly or in part were examined in the light of these examples. It was found that three of them, Bulwick, Harringworth and Polebrook, have plans of a proportion of three squares including the chancel arch (Fig. 12). Of the remainder, Easton-on-the-Hill, Lutton and Yarwell are of between two and three squares including the chancel arch. King's Cliffe is of three squares internally. In this analysis the churches at Woodnewton, Cotterstock and Warmington were excluded as having earlier origins although they have 13th-century arcades.

The general trend was therefore for longer naves, and one third of the twelve conform to a proportion of three squares including the chancel arch. There is no evidence to suggest that any naves were widened at this period or inded at any other time.

The plan of Polebrook church is so similar to that of Duddington that it is suggested they developed in the same way. The differing abnormal positions of the towers appear to have been caused by steeply sloping ground at the W. end of the church. All these 13th-century naves had arcades and N. and S. aisles. At both Easton-on-the-Hill and Wakerley it can be clearly seen that arcades were cut through existing external walls when aisles were added, as earlier nave windows are cut by the arcade arches (Figs. 67, 195). It appears from the incidence of piscinae that aisles were built to house chapels and there is some evidence to suggest that these were screened from the nave.

No nave or aisle roofs of the 13th century survive but the outline of a number can be traced from weatherings and scars, as could those of earlier periods. At Warmington there is the weathering for the roof associated with the nave of c. 1200 on the E. face of the tower which indicates that there was no clearstorey and that the roof had a pitch of about forty-five degrees. Weatherings also indicate that the late 12th-century aisles at Polebrook had roofs pitched at about fifty-five degrees and presumably the nave roof followed the same angle (Fig. 172). The outline of the early 13th-century nave roof at King's Cliffe has a pitch of fifty degrees. These steep-pitched roofs would not have been difficult to cover satisfactorily; stone slate and thatch were available locally. However, aisles of the early 13th century were not always as narrow as those at Polebrook (2.3m.). The S. aisle at Tansor is wide (4.5m.), and there is no direct evidence to show how it was roofed. All aisles now have flat single-pitch roofs which must have gradually become the norm in the late Middle Ages as clearstoreys were built and aisle walls raised in height. These low pitched roofs must have been covered with lead which has always been expensive. It is therefore reasonable to assume that before the introduction of clearstoreys these wide aisles had steep gabled roofs or perhaps transverse gables over the windows (cf. RCHM City of Oxford, monument (32)).

There is evidence for a double-pitched roof in the S. chapel at Easton-on-the-Hill and the N. chapel at Glapthorn; both are 3.7m. wide and of 13th-century date. Each now has a low-pitched roof uniform with the adjacent aisle, and at Glapthorn there is no structural division between the chapel and the aisle. The chapel at Easton-on-the-Hill has the remains of an internal blind arch at its E. end which indicates that this wall was steeply gabled (Plate 34). At Glapthorn the top of the E. window is somewhat higher than the contemporary eaves of the chancel and therefore a former gabled roof is indicated. Because of the position of these examples they may have been given special architectural treatment, but nevertheless they do provide evidence for the use of steep double-pitched roofs in the 13th century.

The plan form of eleven chancels in use during the 13th century can be determined. Five of these are of the same width as their Norman predecessors: Collyweston, Easton-on-the-Hill, Tansor, Woodnewton and Yarwell. It is clear that all of these except Yarwell have been extended to the E. The remaining six at Bulwick, Duddington, Glapthorn, Lutton, Polebrook and Warmington have no identifiable fabric earlier than the 13th century. The relationship between nave and chancel walls is not constant, but generally they were found to be more or less in line. These six chancels built in the 13th century are all therefore wider in relation to the width of their naves than were the chancels of the Norman period.

All eleven chancels have a plan of a proportion which lies between two and a half internal squares at Woodnewton and one and a half squares at Yarwell. A double-square internal proportion would seem to be average as at Collyweston, Glapthorn, and Polebrook. All these chancels, with the exception of Yarwell, demonstrate a new plan proportion. There is evidence for compartments on the N. side of the chancel at both Polebrook and Tansor, but only the doorway now remains at Polebrook. These compartments were presumably vestries. Chancel roofs appear to have been steep-pitched throughout the 13th century and evidence to support this survives in many places for example, Polebrook, Glapthorn and Warmington. Five chancel arches survive from this period; the earliest, of the late 12th century, at Polebrook is the narrowest in proportion to the nave. Glapthorn and Yarwell, of the early 13th century, and Harringworth of later in the same century are wider but still have substantial responds. The chancel arch at Warmington is exceptional as it has no responds, spans the whole width of the nave, and is supported on wall shafts; this anticipates developments in the 14th century. Throughout all these alterations in plan the division between the nave and chancel remained static, that is to say, chancels expanded to the E. and naves to the W.

Apart from chancel, nave and aisles which are common to nearly all churches during this period, several other compartments form further extensions to this developed 13th-century plan. The chapels off the chancels of Easton-on-the-Hill and Glapthorn have already been mentioned, and similar chapels lie N. and S. of the chancel at Yarwell which has arcaded side walls. They formed extensions to the N. and S. aisles which were demolished in 1782 (Fig. 220). Wakerley church was provided with a short aisle or chapel at the E. end of the S. wall of the nave. Furthermore, a number of churches have transepts. At King's Cliffe they lay N. and S. of the central tower and at Woodnewton N. and S. of the early chancel (marked 'central area' on plan). In both cases the general arrangement is Norman or earlier, but the compartments remained in use during the 13th century. It appears that transepts existed in the 13th century at Bulwick N. and S. of the E. end of the nave but these were removed in the late 14th or early 15th century. At Polebrook a N. transept was built during the 13th century to replace one of the late 12th century. This compartment is almost as big as the nave and still retains contemporary wall benches (Plate 16). The function of these compartments will be discussed below.

Towers and broach spires were built in the late 12th and early 13th centuries at Duddington, Harringworth, Warmington, Polebrook and Laxton, and the upper part of the central tower at King's Cliffe was remodelled and a broach spire added. The towers at Polebrook and Laxton were unbuttressed; those at Duddington and Harringworth have pilaster buttresses. Warmington was remodelled in the mid 13th century when a belfry, broach spire and angle buttresses were added; belfries were also built at Tansor and Cotterstock. The towers are built of rough blockwork or rubble with alternating quoins and at Harringworth these are accentuated by the use of ironstone. The belfry, spire and buttresses at Warmington are of ashlar. All spires are octagonal and built of single thickness ashlar; they rise from the top of the tower, the corners of which are bridged by squinch arches internally and weathered externally by plain broaches. At Warmington and Polebrook a series of rough corbels remains inside the lower part of the spire and were presumably used to support interior scaffolding which stiffened the structure during construction. The apex of each spire is built up solid and finished with a boss. There is considerable variation in height, most spires having three tiers of lucarnes, but the smallest only two. Spires weather the tops of the towers and all, except Harringworth which suffered later modification, have a corbel course at this junction. At Laxton and Duddington these are continuous but at King's Cliffe, Polebrook and Warmington, where the central sections of the belfry walls are recessed, the corbel courses are interrupted at the corners. Unlike Romanesque towers, none of these appears to have been occupied. Vices at Harringworth and Warmington are narrow and lead up to a first-floor ringing chamber and then on to the belfry.

Traces of a late 12th-century belfry survive at Glapthorn (Fig. 96). The W. wall of the nave is abnormally thick and central in it, above the estimated level of the contemporary roof, was a semicircular-headed opening looking W. Above the nave behind this wall was a timber turret supported on cantilevers. This belfry remained in use for some time because the single round-headed opening was replaced by a pair of small pointed openings set slightly lower in the wall (Plate 5) and both the tower and clearstorey are of post-medieval date.

There are a number of porches which date from the 13th century, and no earlier examples now exist. All have wide entrance arches and most have steep-pitched roofs and interior benches. Both the N. and S. porches at Warmington are vaulted in stone. All have been extensively rebuilt and repaired.

This analysis shows clearly how small Norman two-compartment churches were expanded to give larger churches of quite different plan. This enlarged form is the main characteristic of these early Gothic churches. It will be seen that the introduction of the pointed arch was somewhat hesitant, and in many cases later than the new plan form. Cross sectional development, that is to say the introduction of clearstoreys and the raising of aisle walls, is a modification mainly of the late Middle Ages.

Early 13th-century Architectural Development

During the early part of the 13th century semicircular arches remained in use in a number of churches over openings of wide span, as well as over doorways. Indeed, it can be seen that five of the twelve naves with the new 'Gothic' proportions discussed above were built with arcades with semicircular arches; these are at Bulwick, Duddington, Easton-on-the-Hill, Glapthorn and Polebrook. In all instances these arches have been recognized as late examples of their type because they occur with Early English decoration or mouldings, ranging from capitals with water-leaf at Duddington to stiff-leaf at Polebrook. These late round-headed arches are also marked by a change in the proportion of arcade openings, culminating in those in the S. aisle at Polebrook, which are exceptionally tall and slender, and in marked contrast to the lower semicircular arched N. arcade of perhaps thirty years earlier (Plate 17).

It is also clear that pointed arches were in use from the beginning of the 13th century. Harringworth tower arch, of c. 1200, is pointed and the capitals are decorated with leaf forms, plain on the N. and full water-leaf on the S. (Plate 13). Warmington provides an interesting example of early arcades of two-centred construction, perhaps of 1200 or a little earlier (Plate 30). The homogeneous nature of the arches of two rectangular orders worked with pointed rolls suggest that both arcades were built at the same time; also, the openings are tall and the columns thin. In contrast to this uniformity, piers are octagonal on the N. but circular on the S., and the capitals have a wide variety of decoration ranging from scallops, normally associated with Norman work, to up-to-date water-leaf decoration. The Early English character is evident in both the abacus mouldings and the water-holding bases, throughout both arcades.

Thirteenth-century entrance doorways with semicircular heads were built at Duddington, Easton-on-the-Hill, Nassington, Polebrook and Woodnewton. The doorway at Duddington is now in a 14th-century aisle wall and the head has been reconstructed as a narrower two-centred arch (Fig. 59). It is interesting to note that two other semicircular arches have also been made pointed; these are the entrance arch of the N. porch at Polebrook which was very slightly altered (Plate 25), and the chancel arch at Wakerley which was more extensively rebuilt (Fig. 195). There is no indication when these changes were made, but the work at Wakerley was a considerable undertaking, executed with great care, perhaps suggesting a medieval date.

The doorways at Duddington, Easton-on-the-Hill, Nassington and Woodnewton have pronounced Early English mouldings and decoration (Figs. 59, 68; Plates 15, 34), while the main doorway at Polebrook is more restrained, as are the priests' doors at Polebrook and Woodnewton (Plate 14). The vestry door at Polebrook is of transitional type and should perhaps be considered with this group as it has a plain chamfered two-centred arch under a semicircular hollow-moulded label.

Arches of the 13th century with semicircular heads occur at Easton-on-the-Hill, between the chancel and the mid 13th-century S. chapel, and in the N. porch at Polebrook (Plate 25), which has multi-roll moulding, stiff-leaf capitals and dog-tooth decoration. It would appear that the latest occurrence of round-headed arches in the area is at Polebrook, both on the evidence of this porch, and the proportion and decoration of the S. arcade. All these semicircular arches are of wide span and perhaps the form was retained because of a conservative attitude to construction although the masons were clearly conversant with new Early English work as demonstrated by their use of up-to-date decoration and mouldings, and by the occurrence in the area of contemporary examples of pointed arches with similar decoration. There seems to have been no hesitation in adopting the new pointed head for windows but these openings were narrow and can have presented little or no structural problem. Semicircular heads were only used in the low level windows of the towers at Duddington and Polebrook. There are also transitional windows with twin pointed lights within a semicircular surround at Duddington in the belfry stage of the tower and in the N. vestry at Tansor. All other windows of the laste 12th and early 13th century are of lancet type with pointed heads, even when the rear arch is still semicircular as at the E. end of the S. aisle at Polebrook.

The high proportion of late 12th and early 13th-century work which survives in this area has provided much information on the transition from Romanesque to Gothic. It has been possible to demonstrate the evolution to an expanded plan type, and to examine the architectural context in which this expansion took place. The reasons for this widespread rebuilding of churches during the 13th century are not immediately apparent. Further historical studies, beyond the scope of this survey, may provide an explanation.

Internal Arrangement

The broader aspects of structure have been examined and it is now necessary to review the more detailed evidence relating to the use of these buildings during the 13th century. Evidence consists primarily of the detail of the fabric, and features which are built into it. The most complete example of an early 13th-century chancel is at Polebrook. The piscina in the S. wall indicates the position of the main altar. There is a priest's door in the S. wall towards the W. end and at the W. are a pair of low-side windows, one on each side of the chancel. They are rebated to take external shutters in the lower part and presumably indicate the positions of reading desks or seats for the clergy. Piscinae at Polebrook, Tansor, and Woodnewton are double and at Glapthorn there are two separate piscinae in adjacent window sills presumably affording the same facility for separate washing of communion vessels and the priests' hands as was customary during the 13th century (F. Bond, The Chancel of English Churches (1916), p. 146). Vestries were not universal in the 13th century, and in this area only one, at Tansor, remains and another, at Polebrook, is indicated by a doorway. The vestry at Tansor is constructed within an earlier compartment and has screen walls (Plate 12). All other surviving 13th-century compartments off chancels were chapels, that is to say at Easton-on-the-Hill, Glapthorn, Woodnewton and Yarwell, and all except the last have piscinae; that at Glapthorn is in the form of a pillar (Plate 41). The tower at Duddington has openings into both the chancel and the S. aisle and was fitted out as a chapel.

At Polebrook there is also evidence indicating how other compartments were used. The S. aisle had an altar at its E. end in the 13th century, marked by the double piscina, now in the 14th-century chapel, S. of its former position. The N. transept was clearly intended as a large chapel. It had an altar against the E. wall under a window, and the N. and W. walls were furnished with a splendid set of canopied seats in the form of wall arcades set above stone benches. No record is known of this chapel but its arrangement suggests a collegiate foundation (Plate 16). There are also piscinae in the aisle at Tansor, Wakerley and Warmington, which indicate the existence of chapels. There are indications at both Tansor and Warmington that each had two chapels in the S. aisle, the western probably having a freestanding reredos or screen behind the altar. How these chapels were enclosed is not clear but at Warmington the plinth block of the second column of the S. arcade is shaped perhaps to accommodate the corner of a screen running just S. of the arcade piers.

It would appear that the enlarged plan of the 13th century provided greater space for the clergy and put the main altar further away from the nave, which in most cases was also extended. Other compartments appear to have been occupied by secondary altars and chapels. This arrangement is in contrast to the two-cell. Norman plan which had no ancillary space so that secondary altars had to be accommodated within the nave on each side of the chancel arch as at Wakerley.

No Romanesque fonts survive except perhaps for a rest bowl at Blatherwycke, but 13th-century examples remain at Duddington, King's Cliffe, Polebrook, Wakerley and Woodnewton (Plates 38, 39). They are all sited near the principal entrance of the church and, except for that at Wakerley, in aisles. This position may be contrasted with that of most of the later medieval fonts which are on the centre line of the nave towards the W. end, as at Collyweston, Cotterstock, Easton-on-the-Hill, Fotheringhay and Warmington. The consistent siting of early and late fonts suggests that they are in situ and may indicate some major change in the practice of baptism in the later Middle Ages. The font at Lutton, of early 14th-century date, provides certain evidence for position, as it forms part of the composition of the S. arcade and is contemporary with it (Plate 39). It is adjacent to the S. door of the church, which is the principal entrance, and thus lends support to the idea that most early fonts may be in situ.

With the possible exception of some bench ends at Polebrook, no wooden furniture survives from this period, but a number of stone benches can be associated with 13th-century fabric. Glapthorn and Warmington churches have plain wall benches in the chancel and Yarwell has rather narrow benches in the N. and S. chapels off the chancel. The N. arcade of the nave at Glapthorn has exaggerated pier plinths which may have been built as seats, and the N. aisle at Tansor has a wall bench along its N. and W. walls. There are similar benches in the N. and S. aisles at Cotterstock; those in the S. aisle are presumably 14th-century but perhaps reflect an earlier arrangement. All stone benches stop short of the E. end of the aisle in which they occur, presumably to allow space for an altar. The arcaded seats in the N. transept at Polebrook have already been mentioned, and a parallel can be made with those in the S. porch at Warmington.

Later 13th-century Architectural Development

The mixture of architectural styles which occurred at the end of the 12th century and at the beginning of the 13th century have been discussed up to about 1230 when the use of the semicircular arch appears to have died out. A style was emerging during this period which seems to have persisted well into the second half of the century. The detail of this work is in the main unexceptional, and follows the normal course of Early English architecture. None of the work can be closely dated and the conventional stylistic development covering the period has been accepted. However, there is some evidence to suggest that as the style developed, early and late forms were used simultaneously. Examples can be found in the N. aisle at Nassington, the S. aisle at Warmington and the S. wall of the chancel at Glapthorn (Plates 21, 24, 30). It is always difficult to be certain that features have not been reworked or replaced but in the examples given the fabric of the wall looks undisturbed and at Nassington wall-painting survives on the rear arches of many of the windows.

Warmington church was transformed in the 13th century. A new chancel was built, the clearstorey constructed and the N. and S. aisles rebuilt wider and higher (Fig. 202). The W. tower was also heightened and a broach spire built. The work when looked at in the context of the development of the plan and section of the building has the appearance of a unified scheme. However, the upper parts of the tower, the spire and the S. aisle are in developed Early English style which cannot be much later than c. 1250, while the clearstorey, the N. aisle and the chancel have windows consisting of two main pointed lights with a quatrefoil in the head, typical of the early Decorated style. No independent evidence exists to indicate the date of this work, but if the suggestion that it forms part of a unified campaign is accepted then it should not be very different in date from the developed Early English work.

The source of this work is also difficult to determine without documentary evidence. It may be that it was the product of the main stream of early Decorated architecture dependent on work at Lincoln or even Westminster, but it is also possible that it may have been derived at least in part from more local Early English sources. Certainly all the elements to support this view have been found within the Inventory area: single lancet windows, their use in pairs, the introduction of a shaped opening between the heads of the lights, first perhaps oval and then circular, can all be seen at Tansor and in the S. wall of the chancel at Glapthorn (Plates 18, 24). It is then only necessary to look at the N. chapel window, also at Glapthorn, to see the process complete except for cusping within the roundel, which can be found at Duddington in the E. window of the N. aisle (Plate 27) or in the belfry at Cotterstock.

Whatever the origin of the decorated work at Warmington, it would be logical to suggest that it is a very early occurrence. It is also clear that the building broke with 13th-century form and may have set a standard for the later development of the churches of the area.

Fourteenth Century

There was no major advance in plan form during the 14th century but the cross section of the body of a number of churches was altered, following the example set at Warmington. Work generally consisted of the widening of aisles, the rebuilding of arcades and chancel arches, and the construction of clearstoreys. Building activity was less than in the previous century, giving the impression of consolidation after advance. There were, however, three works of considerable scale, and possibly a fourth of which only part now remains. Early churches at Blatherwycke and Wakerley, which had survived the changes of the 13th century more or less intact, were much altered. Cotterstock church was remodelled as a result of the benefaction of John Gifford, and it may well be that a rebuilding was undertaken at Southwick by John Knyvet, but only the tower and spire remain. The work of the 14th century has been tabulated in column 4 of Fig. 9. The development of plan form was limited. A large chancel was built at Blatherwycke and transepts were removed at Bulwick. The very large choir that was constructed at Cotterstock cannot be considered in the strict context of parish church development as it was built for a college of priests. The only widespread change was the enlargement of chancel arches at Blatherwycke, Bulwick, Collyweston, Cotterstock, Duddington, Easton-on-the-Hill, Lutton and Nassington. The desire for a wide chancel arch was so strong that at Easton-on-the-Hill, which has a narrow chancel, the responds were set back within the line of the chancel walls. This unsatisfactory solution was avoided at Blatherwycke and Lutton where the chancel arches are carried on corbels. No chancel screen survives from this period but the arches at Collyweston and Bulwick have shallow grooves in the soffit presumably to accommodate timber tympana set above screens. This suggests that the increased opening between nave and chancel was made to house larger and perhaps more elaborate screens and tympana, and not to provide a better connection between nave and chancel.

A chapel was built at Easton-on-the-Hill, opening off the chancel, and another was built at Polebrook, off the S. aisle. These additions probably did not increase the number of altars in either church, but they perhaps show that larger chapels were desired. More importantly they demonstrate the way in which fully developed churches with chancel, nave and aisles could be extended with the minimum of disruption to the existing fabric, by breaking away from a strictly E. and W. arrangement of compartments.

The major building activity of the period was the reorganization of the main body of the churches at Bulwick, Cotterstock, Duddington and Harringworth. In all cases the plan of the nave remained unchanged, but the walls were raised to form a clearstorey which was covered with a low-pitched roof. This type of roof was suitable for the high, less stable, walls of the clearstorey and also allowed the level of the apex of the roof to remain more or less unchanged. Aisles were widened, except for that on the N. at Duddington, and covered with low-pitched lean-to roofs which allowed for the maximum height of aisle wall and an unobstructed clearstorey. The interior of the churches, formerly dominated by steep-pitched roofs and lit by narrow windows in low walled aisles, became lofty spaces, well lit from above and from spacious aisles with larger windows. This change also had its effect externally as low aisle walls with perhaps a narrow clearstorey dominated by large areas of roof gave way to elevations of wall and window. All four churches demonstrate how this new form was used to create elevations of some architectural quality and it is not surprising that the S. sides, those with the principal entrances, were singled out for special treatment. Both Bulwick and Harringworth have S. aisles with fine ashlar walling and large traceried windows. Duddington has a unified elevation with similar windows at both aisle and clearstorey level.

In contrast to the almost total rebuilding of aisles in these four churches, nave arcades received less drastic treatment. Those at Cotterstock and Duddington of the 12th and 13th centuries have survived but at Bulwick round-headed arches were made pointed (Fig. 35), and only at Harringworth were they entirely replaced. Aisles were also rebuilt at Easton-on-the-Hill, Glapthorn, Lutton and Nassington and all have lean-to roofs.

There are three towers with spires, all stylistically similar, at Bulwick, Southwick and Wakerley. Each tower has a parapet which masks the base of a slender octagonal spire with two tiers of lucarnes. The earliest of the group is at Southwick where the tower and spire have the arms of Knyvet and a variation of the arms of Basset, indicating that it was built for John Knyvet (d. 1381) after his marriage to Eleanor Basset, an heiress, and presumably after the death of his father Richard in 1352. Inside the tower are four head corbels which were placed there to carry a vault which was never constructed. These corbels are very similar to those in the undercroft of the S. block at Southwick Hall and it is suggested that this work is probably contemporary with the church tower and was also built by John Knyvet. At Bulwick and Wakerley towers and spires are of a type similar to that at Southwick, but they are larger and may be considered as a pair. Shared details include belfry openings, similar buttresses at the upper level, decorative bands of quatrefoils below crenellated parapets and spires with ribs on the angles, although the spire at Wakerley is highly decorated with crockets. These towers were probably built in the 14th century or perhaps early in the 15th century, but they, and other closely connected fabric, have been included with 14th-century work in column 4, Fig. 9, because of the stylistic affinity with Southwick.

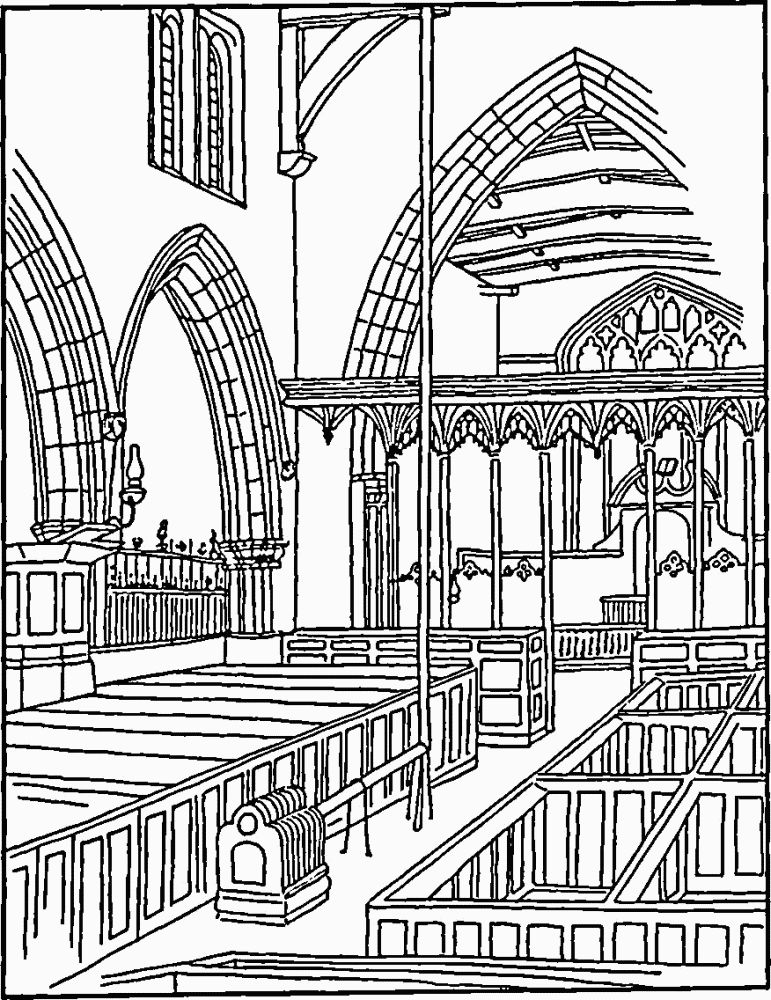

There is one other example of firmly dated work in the 14th century, the choir of the college founded by John Gifford at Cotterstock in 1338. Before this time the parish church had been a modest structure consisting of a chancel, nave without clearstorey, narrow aisles and a W. tower. The college consisted of a Provost and twelve clerks, and to accommodate this considerable community the chancel was rebuilt on a large scale, and residential buildings were constructed N. of the church. The church W. of the chancel arch was retained by the parish, and the nave remained unaltered in plan, but a clearstorey was added and the aisles were rebuilt perhaps a little wider. Nothing survives of the residential buildings except part of the W. wall of a narrow building adjoining the chancel but Church Farm (Cotterstock (15)) occupies at least a part of the site. The college was generously endowed by John Gifford and as a part of those arrangements the Rectory of Cotterstock was made over to the Provost and clerks in January 1340. Much of the medieval arrangement of the chancel survives despite a very extensive restoration by G. E. Street in 1876. There are two 14th-century doorways in the N. wall: that on the E. opens into the vestry of 1876 which was built on the footings of the building which linked the church to the residential quarters; the other on the W. gives access to the chancel from the outside. The present chancel floor is all of 1876 but on the evidence of the thresholds of these doorways, the levels appear to respect the original arrangement of three zones in the manner of a conventual choir. The sanctuary was at the highest level and was divided from the choir by a lower area defining the presbytery. There is also some evidence for the arrangements at the W. end of the chancel. Two doorways survive at the N.W. corner; the lower one gave access to a stair which stood in the N. aisle, and the upper at the top of the stairs led onto a gallery within the chancel, of which no trace survives. This arrangement suggests a pulpitum rather than a rood screen, and may have consisted of a verandah-like structure. There is little evidence to show how the W. part of the church was used, but the. S. aisle was only slightly smaller than the nave. It was furnished with a squint when the choir was built and had an altar at its E. end. This may have been the main parochial altar as there is no trace of it having been in the restricted nave.

Ashlar was used much more widely in the 14th century than century hitherto and is of variable quality. The best work is in the chancel at Cotterstock and at Harringworth at the E. end of the S. aisle, where the fine-jointed limestone blockwork is banded with courses of ironstone. The S. aisle at Nassington provides an example of poor quality work where the ashlar has in some areas deteriorated into coursed rubble. Coursed rubble was used for clearstoreys and for other works, for example the aisles at Cotterstock and the S. aisle at Lutton. Towers and spires are, as would be expected, of ashlar. Both rubble and ashlar are of local Oolitic Limestone.

A number of 14th-century fittings survive, the majority of which are built into the fabric of the churches. Piscinae are of two types, single and combined with a sedilia. The former are found in most chapels in aisles which were rebuilt at this time, but the latter occur at Bulwick, Cotterstock and Harringworth. Stone benches were built in the aisles at Cotterstock, and a number of timber bench ends with scroll tops of late 13th or more probably 14th-century date survive reused in the S. chapel at Polebrook. These benches perhaps indicate that seating in the body of the churches was coming into use as preaching became more common during this century.

Fifteenth Century

Building activity during this period continued in much the same way as it had in the previous century with the rebuilding of towers and chancels and the construction of a number of clear-storeys. With the exception of the collegiate church at Fotheringhay, there was no marked increase in the size of churches, or alteration from the plan form which had been reached in the 13th century. Four works, at Apethorpe, Collyweston, Fotheringhay and King's Cliffe, dominate the building activity of the period. The first three are known to have been instigated by powerful patrons and this may also have been the case at King's Cliffe. Fig. 9, column 5 shows the extent of 15th-century work in the area. The church at Apethorpe is exceptional in that it owes very little to the structure it replaced except perhaps for the position of the chancel arch, which may have been inherited from the previous church, as at Fotheringhay. Most of the 15th-century building survives and gives a clear impression of modest parish church architecture at this time. The plan and section make no departure from the form evolved in many churches during the Middle Ages except that side entrances are towards the W. end of the nave, reverting to the position common in Norman churches.

The churches at Collyweston, Easton-on-the-Hill, Lutton. King's Cliffe, Nassington and Woodnewton have clearstoreys of the 15th century, and the first three also have towers of this date. Easton-on-the-Hill also has a 15th-century clearstorey over the chancel. The clearstorey at Woodnewton and that of the 14th century at Tansor do not respect the earlier divisions between nave and chancel. Both naves were extended eastwards at the expense of the W. parts of the chancels, a most unusual occurrence, and the E. walls of the clearstoreys were carried on new thin arches; at Tansor the arch is of timber and at Woodnewton of stone. Before these rearrangements it appears that there was no chancel arch at Tansor but at Woodnewton the arch was of masonry and stood at the point where clearstorey and lower wall set in on the S. side of the church. There is no indication as to how these new arrangements affected ritual or the division of ownership between nave and chancel.

In other churches alterations of a less complex nature were carried out. Chancels were rebuilt at Harringworth, Nassington and Wakerley, and it is probable that each follows the outline of its predecessor. The short chancel at Wakerley, although of the 15th century, may follow a Norman outline, the positions of the N. and S. walls of which are clearly defined by 12th-century details.

These new churches were given flat-pitched roofs, as was the refurbished chancel at Warmington where the new roof cut across the 13th-century chancel arch. This awkward junction must have been masked by a tympanum. An alteration frequently made during the 15th century was the replacement of windows, particularly the E. windows of chancels, as at Collyweston, Easton-on-the-Hill, Tansor, Warmington, Woodnewton and Yarwell. At Glapthorn church the aisles were almost entirely refenestrated.

The churches at Collyweston and King's Cliffe were considerably rebuilt during the 15th century. At King's Cliffe the work can be divided into two phases: the first, early in the century, consisted of the rebuilding of the nave, aisles, and S. transept, and the second, later in the century, of the chancel, and N. transept. The church was therefore totally rebuilt with the exception of the central tower, but without any great change in plan. As at the churches of Apethorpe and Fotheringhay, N. and S. entrances are at the W. end of the aisles; nothing now remains to show the earlier arrangements, but it is clear that the plan of the nave was not enlarged when rebuilt. Regular design was achieved by the uniform spacing of the clearstorey and aisle windows and by identical treatment of the N. and S. sides of the body of the church.

The other church which was considerably rebuilt in the 15th century was at Collyweston. This was probably carried out under the patronage of Lady Margaret Beaufort who acquired the manor in 1487, and a date of c. 1490 is suggested for the work. Compared with the scale of the buildings carried out in her name at Cambridge and elsewhere the work at Collyweston is modest. The plan of the nave and chancel remained unchanged, but a large chapel was built on the S. of the chancel, presumably for the personal use of Lady Margaret. Access was from the chancel and a view of the main altar was gained by a large squint in the form of a two-light window. In addition to the rebuilding of the body of the church a W. tower was constructed. New windows in the S. wall of the nave are of unusual design; they are large, rectangular, and of three lights, with very shallow cusping. A similar window in the N. transept at King's Cliffe might suggest that this transept and the chancel are also of c. 1490.

Apethorpe church was entirely rebuilt in the late 15th century, much in the style of the work at Collyweston; the nave arcades are particularly alike (Figs. 20, 43). The rebuilding may have been influenced by Sir Guy Wolston who built Apethorpe Hall soon after he acquired the manor in c. 1480. The plan makes no innovation except perhaps for the positions of the nave doorways. The elevations of this church exhibit a sense of design similar to the work of the first phase at King's Cliffe; the symmetrical section of the nave and aisles with its low-pitched roofs, the high walls and the uniformity of architectural detail all reinforce this impression of deliberate regularity.

The parochial nave of the church at Fotheringhay is exceptional (Plate 46). Commissioned by Richard third Duke of York to complement the collegiate choir which was the conception of Edward second Duke of York, this nave is a work of almost Royal status and thus has little connection with the locality. The large scale and carefully considered detail of the architecture clearly separates Fotheringhay church from the humbler parish churches of the area. The whole church was built between 1415 and 1441 and it is known that the nave was started soon after 1434. According to the contract much of the detail was derived from the choir and therefore the design of the nave must be to some extent considered a product of twenty years earlier.

There are four towers of the 15th century, at Collyweston, Easton-on-the-Hill, Fotheringhay and Lutton. The designs are broadly similar, having clasping buttresses, crenellated parapets and no spires. This last characteristic distinguishes them clearly from the towers of the 13th and 14th century all of which were built with spires. However, the tower at Fotheringhay was built with an octagonal lantern and the very much earlier tower at Nassington was crowned with a spire on an octagonal base of the 15th century. The towers of the churches at Collyweston and Easton-on-the-Hill are very similar and both have particularly large crocketed octagonal finials at each corner. A comparison may be made between these towers and those at the churches of St. John and St. Martin in Stamford (RCHM, Stamford (30), (31)). The Stamford towers appear to be the earlier and may therefore be a source of design.

There was little change in building materials during the 15th century; both rubble and ashlar were used, all of which came from local sources. However, the proportion of work executed in ashlar appears to be higher than before and the stone usually chosen was fine-grained which allowed for accurate cutting and precise jointing.

Surviving medieval roofs are all of 15th-century date. Nave roofs at Apethorpe, King's Cliffe and Lutton are low-pitched and of similar form, with cambered principal rafters, wall posts and brackets alternating with plain cambered intermediate principals, supporting ridge and side purlins which carry the common rafters. The nave roof at Fotheringhay is similar but has no intermediate principal rafters. Contemporary aisle roofs survive at Apethorpe and Fotheringhay; both have braced principal rafters which support purlins and common rafters which span the width of the aisle as a lean-to roof. At Fotheringhay there is a set of short rafters which span from the arcade wall to a 'ridge' purlin, so imitating a symmetrical roof when viewed from below. The uniform picture which is given by these nave and aisle roofs may be contrasted with the two 15th-century chancel roofs which survive at Easton-on-the-Hill and Polebrook; both are of steeper pitch and of individual design.

It is clear that the plan form of churches did not alter greatly during this time and it also appears that the position and number of altars remained much as they had been in the 14th century. A large group of fittings survive from this period, providing information on some aspects of internal arrangement. Earlier chancels do not appear to have been refurnished in the 15th century. The new chancels at Harringworth, Nassington and Wakerley show no innovation in arrangement. The floor levels at Nassington are similar to those of the choir at Cotterstock which suggest a division into sanctuary, presbytery and choir. Several stalls of high quality which came from the collegiate choir at Fotheringhay survive at Tansor and Hemington (Plates 54, 55). Evidence for the presence of former chancel screens and rood lofts is plentiful. Rood stairs survive at Bulwick. Duddington, Easton-on-the-Hill, Harringworth and Warmington and brackets for a rood beam also remain at Apethorpe, flanking the chancel arch on the W. side. Rood screens survive at Harringworth and Warmington and some fragments of a screen form part of the 17th-century nave seating at Easton-on-the-Hill. The screen at Harringworth suffered little damage and still has its loft (Plate 33). No chapel screens or furniture survive, but there is some nave furniture including a pulpit of exceptional quality at Fotheringhay and late medieval seating in a number of churches. Some bench ends were reused at King's Cliffe after their removal from the nave at Fotheringhay in 1817. A few 15th-century fonts survive, most of which are sited on the centre line of the nave towards its W. end. This position is in contrast with the siting of earlier fonts, and occurs at Collyweston, Cotterstock, Easton-on-the-Hill and Fotheringhay.

Decoration of Wall Surfaces of Medieval Churches

The interior wall surfaces of most churches in the area are plastered but those at Cotterstock, Southwick and Woodnewton have been stripped to show stonework, as have the chancel walls at Tansor. This work was carried out in the 19th century or later and is particularly unfortunate at Cotterstock and Woodnewton where the rubble walls have been pointed with raised joints and at Southwick where all traces of the 18th-century interior have been removed including plaster ceilings. Laxton church was rebuilt in 1867 and the interior wall surface of coursed squared rubble was left unplastered.

The walls of the remaining eighteen churches are plastered internally and have generally been whitewashed but fragments of wall painting can be seen in a small number of churches. The earliest example may be at Tansor where there is foliated scroll-work of 12th-century style on the soffit of the semicircular arches of the nave arcade, but this work has been repainted in modern times. Painting of the 13th century is visible in three churches. At Easton-on-the-Hill there is a small area of architectural painting showing blockwork decorated with flowers and an outer order of chequer-work voussoirs framing part of an arch of the nave arcade (Fig. 67). At Polebrook, in the N. transept, there are traces of two nimbed figures each occupying an arch of the blind arcade. A short length of foliated frieze survives in the N. aisle at Glapthorn.

Fourteenth and fifteenth-century painting can be seen at Glapthorn and Nassington, both of which have areas of 14th-century architectural painting showing blockwork with flowers and traces of Doom paintings of the 15th-century on the E. walls of the naves. Nassington also has in the N. aisle a number of nimbed figures, a Wheel of Fortune and a scene of St. Michael weighing souls, all of the 14th century, and a scene showing St. Martin of Tours, of 15th-century date, in the nave. At Glapthorn there is a large figure of St. Christopher, also of the 15th century, in the N. aisle opposite the S. door. No painted plasterwork survives from the post-reformation period. There is, however, a watercolour painting showing a 'shadow' of the tomb of Elizabeth I which was formerly on a wall in Cotterstock church (K. A. Esdaile, St. Martin in the Fields New and Old (1944), 58).

Exterior wall surfaces of churches vary from fine ashlar to the coarsest rubble and are now bare except for small areas at King's Cliffe and Fotheringhay. The clearstorey at King's Cliffe is built of rubble with freestone dressings and an area of plaster survives on the exterior of the N. wall. It surrounds a window and is feathered out so that only a uniform freestone surround remains visible. The quoins of an adjacent window are very irregular and flush with the wall surface and it is suggested that they were always intended to be covered with plaster. There is no other direct evidence for this treatment of rubble walling but throughout the Middle Ages windows within this type of masonry have very irregular quoins which were presumably meant to be hidden. No finish can be seen on the plaster at King's Cliffe but at Fotheringhay the fine ashlar of the W. tower appears to have been covered with a thick layer of limewash. These two fragments suggest that the exterior of churches during the Middle Ages were more uniform than they now appear and that sometimes at least they were whitened with limewash.

Post-Reformation

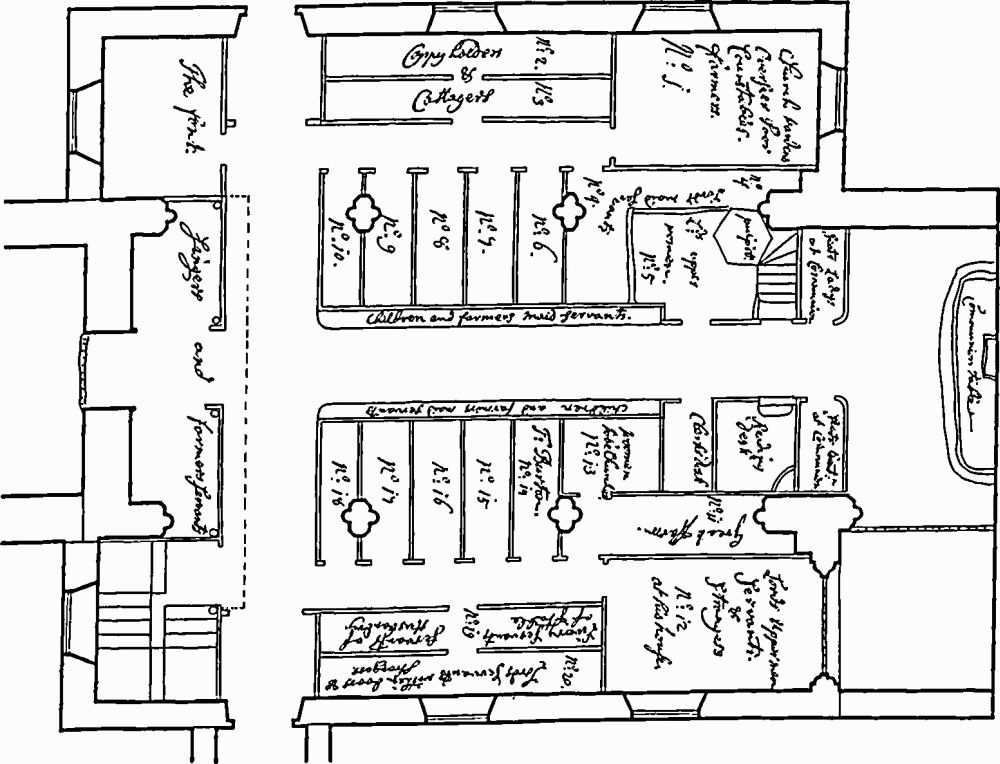

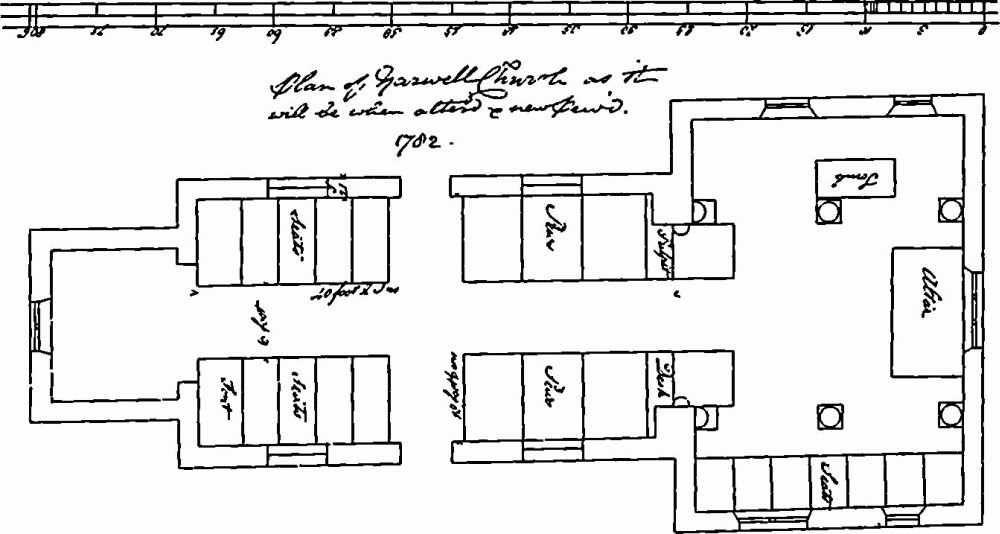

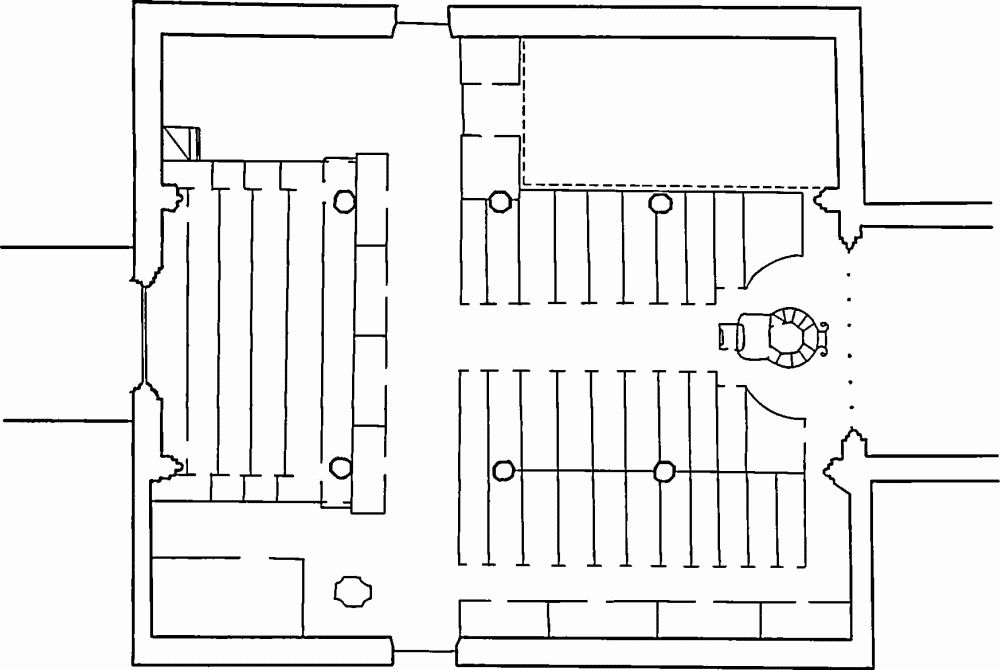

After the Reformation the form of most churches in the area remained unchanged but because of the thorough restorations undertaken during the 19th and early 20th centuries little survives to show how interiors were adapted to meet the demands of new liturgy or architectural fashion. Work carried out in the 16th and 17th centuries was broadly in Gothic style, and although some detail shows classical influence, the style can be described as 'Gothic Survival'. Changes in plan form occurred only at Apethorpe, Woodnewton and Hemington. Elsewhere building work was limited to repair or replacement on the old lines. The shells of two churches rebuilt in the 18th century in the classical style, survive at Southwick and Yarwell, but most of the classical detail has been subsequently removed. Only the chapel at Ashton, built in a mixture of Gothic and Classical styles, remains unaltered. During the 19th and 20th centuries there was little new building and ancient structures were treated with respect, although interiors were generally refitted in the Gothic taste.