An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Oxford. Originally published by His Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1939.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Oxford(London, 1939), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/oxon/xviii-xxxiii [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Sectional Preface', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Oxford(London, 1939), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/oxon/xviii-xxxiii.

"Sectional Preface". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the City of Oxford. (London, 1939), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/oxon/xviii-xxxiii.

In this section

OXFORD CITY

Sectional Preface

(i) Earthworks.

Apart from the lofty and fairly well-preserved motte at Oxford Castle, the earthworks of the city are inconsiderable. The city-moat has been almost entirely filled in and the remains of the Civil War earthworks are negligible.

(ii) Ecclesiastical and Secular Architecture.

Building Materials.

Oxfordshire being a stone county, practically all the Oxford buildings are constructed of local materials. The numerous stone-quarries of the county, belonging to the Upper, Middle and Lower Oolitic formations, have been the subject of an article by Mr. R. W. Jeffery in the Victoria County History Vol. II. In mediæval and later times the main sources of stone have been the Headington and Taynton (near Burford) quarries, the former being used for structural and the latter for decorative work. The building-accounts of Merton, for the end of the 13th and the 14th centuries, show an extensive use of Taynton stone, but the place of Headington is here taken by other quarries in its neighbourhood, such as Wheatley, Cuxham, Cowley and Elsfield; Bladon, N.W. of Oxford, is first mentioned in 1378. Taynton stone was used for a new library at Exeter in 1383. At All Souls the stone used from 1437 to 1442 was from Taynton and Headington and at Magdalen from 1467 onwards the stone came from Headington, Wheatley, Thame and Milton under Wychwood. At Christ Church the stone used in the early 16th-century buildings was obtained from Headington, Burford, Taynton and Holton near Wheatley. Taynton and Headington stone continued to be used throughout the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries; the Fellows' Quadrangle at Merton and Wadham College are mainly built of Headington stone. From the middle of the 16th century onwards a considerable use seems to have been made of the dissolved religious houses of the neighbourhood as stone-quarries; thus Abingdon Abbey seems to have been almost completely robbed to the foundations and the same was probably the case at Eynsham Abbey, Oseney Abbey, Rewley Abbey and the Friars' houses in the city. Headington stone, particularly those beds used in the 17th and 18th centuries, has proved little resistant to modern atmospheric conditions, as may be seen from the present condition of such structures as the Library at Christ Church and the Fellows' Building at Corpus Christi. This surface-decay has rendered necessary the almost complete refacing of parts of Peckwater Quadrangle at Christ Church, Queen's College, the Judge's Lodging, etc.

The stone slates used in covering the great majority of Oxford roofs are also of local origin. Stonesfield was a well-known quarry in the 17th century and is still occasionally used.

Timber-framing was extensively used in Oxford from the middle ages to the 18th century, but chiefly for domestic buildings. Brick was sparingly used in the 18th century but even now it is not a prominent feature in the buildings of the city.

Ecclesiastical and Collegiate Buildings.

In the early middle ages the city of Oxford contained 15 parish churches—St. Martin Carfax, St. Ebbe, St. Mary the Virgin, St. Peter in the East, St. Budock, St. Mary Magdalen, St. Aldate, All Saints, St. Mildred, St. Michael North Gate, St. Peter le Bailey, St. Edward the Martyr, St. Frideswide, St. Clement and St. Thomas the Martyr with chapels of the Holy Trinity, St. Michael S. Gate, St. Cross Holywell and St. Peter Wolvercote. Of these churches St. Budock, St. Mildred, St. Edward the Martyr, St. Michael S. Gate and Holy Trinity have been destroyed but the rest survive. The new boundaries of the city also include the parish churches of Cowley, Headington, Iffley and Binsey. Many, if not most of the parish churches date from before the Conquest, but the only structural survival of that period is the tower of St. Michael North Gate, built in all probability in the early part of the 11th century. To the same period belong two fragments of tomb-slabs (Plate 9) now in the Ashmolean Museum, one found on the site of the New Schools in 1882, and one recently found on the site of a new building opposite the Town Hall. The broken slab preserved at the cathedral should probably be placed also within the limits of the same century.

The Queen's College. Mediaeval Chapel.

The earliest post-Conquest building in Oxford is the chapel of St. George in the Castle, of which the reconstructed crypt survives together with the lofty St. George's tower which stood at the W. end of the chapel and may have served as its belfry. The crypt has carved capitals of the crudest late 11th-century character and the great tower with its lack of freestone quoins and its numerous offsets is of much the same date. The middle of the 12th century is well-represented by the two fine churches of St. Peter in the East and Iffley; the former has a crypt and vaulted chancel with unusual detail and the rich decoration of the latter has long rendered it well-known as an example of English Romanesque. There are remains of the same period in the church of St. Ebbe. The chapter-house doorway at the cathedral dates from the second half of the century and the rebuilding of the cathedral itself to rather later in the same half-century. Though small in scale the cathedral is a remarkable example of the design of the period and actually was, or was intended to be, a church completely vaulted in stone. The combined main arcade and triforium had been earlier experimented with at Romsey Abbey and Jedburgh Abbey and was to be copied in a more Gothic form at Glastonbury. To the 13th century belongs the greater part of the beautiful chapter-house at the cathedral, the upper part of its tower and spire, the extension of the chancel at Iffley and also the major portion of the church of St. Giles; this church has an unusual series of gabled chapels on the N. side. The splendid tower and spire of St. Mary's are examples of the 13th and 14th centuries, but the greater part of this spacious church was re-built in the 15th century. The other churches are not of any outstanding interest. About 1500 the remodelling of the cathedral was begun and the remarkable vault constructed over the presbytery.

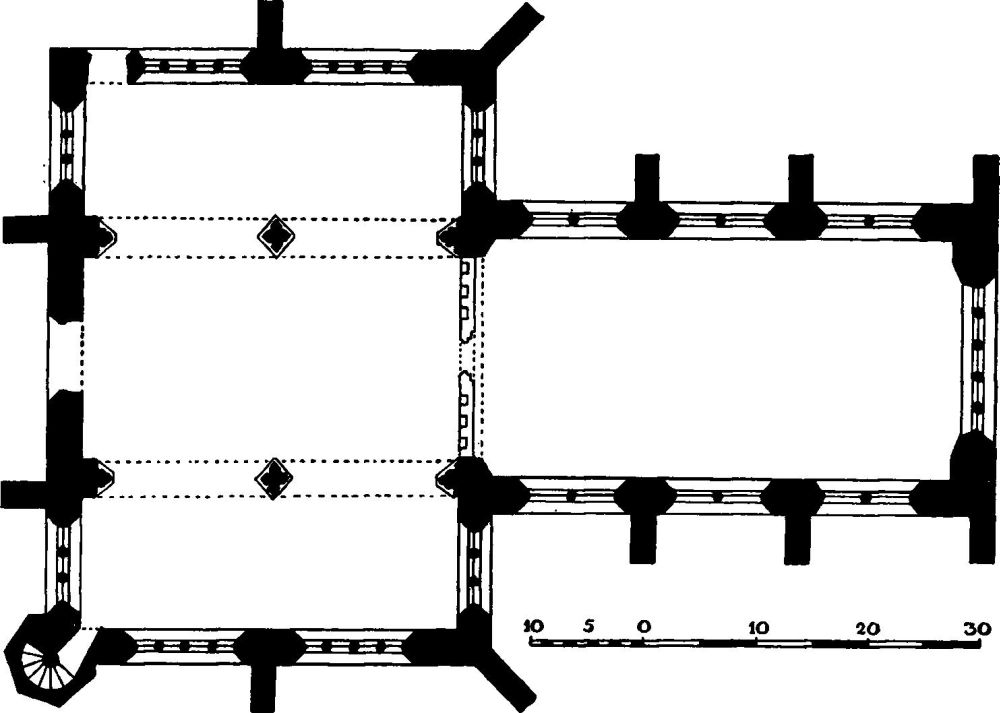

The earliest of the college chapels is the uncompleted cruciform structure at Merton which is an admirable example of the end of the 13th century with 14th and 15th-century additions. The three chapels at New College, All Souls and Magdalen stand together as examples of the last period of Gothic architecture and bear a general resemblance to one another; all are timberroofed and have double arcades across the ante-chapels. The addition of an ante-chapel to the 14th-century chapel at Queen's, brought this structure also into the same category and a plan of the building (here reproduced) was made, fortunately, before its destruction early in the 18th century. The early 16th-century chapel of Corpus Christi is a simple rectangular building of its period, but of the great chapel designed for Cardinal Wolsey at Christ Church and never proceeded with, not even the plan has been preserved.

The stone vaults of the Divinity School (1480–83) and the presbytery of the Cathedral (fn. 1) (c. 1500) are highly remarkable examples of late Gothic vaulting which though actually of lierne type have the elaborate pendants generally seen with fan-vaulting. The construction at the Divinity School is more bold and apparent, the main cross-ribs being largely concealed at the Cathedral; at the Cathedral also the side bays are roofed by cross barrel-vaults which are not represented at the Divinity School.

Apart from these two examples the mediæval churches and chapels of Oxford show the usual English a version from stone-vaulting. Only minor buildings are covered in this manner, such as the chancel at Iffley, the crypts of the castle chapel, St. Peter in the East and St. Aldate, the Congregation House at St. Mary the Virgin, the porches of St. Peter in the East and St. Michael North Gate, the vestibules of All Souls and Magdalen chapels and the Hall staircase at New College. In addition to these mention may here be made of the vaulted domestic crypts at the Mitre Hotel, Nos. 106–107 High Street and at the Town Hall. The best mediæval roofs surviving are those over the chapel at All Souls and the nave at St. Mary the Virgin, both of the 15th century. The former is of hammer-beam type, as is the early 16th-century roof of the hall at Corpus Christi. Another mediæval roof, of hammer-beam type, from St. Mary's College, has been re-used over the chapel at Brasenose.

Before further describing the actual architecture of the colleges and their chapels it will be as well to consider the general form and characteristics of their plan.

The essential features of the fully developed mediæval College-plan consisted of the Hall and Kitchen, the Chapel, the Library, sets of chambers for the members of the college and their head and a gatehouse. Normally these features were built round a central quadrangle, though it is likely that the earliest collegiate buildings were the result of more haphazard planning and the relative positions of the hall and chapel at Merton show that here, at any rate, the early arrangement did not include a formal quadrangle. The Hall followed the normal type of the mediæval domestic hall with a dais at one end and screens at the other, behind which were doors communicating with the buttery and kitchen. The Hall at Merton dated from the 13th century but has been almost entirely re-built. Halls of the late 14th and 15th centuries survive at New College, Balliol, Lincoln and Magdalen and the early 16th-century hall at Christ Church is the largest of the mediæval halls. This hall and that at New College were, from the beginning, built on an undercroft or lower storey and several of the other halls had cellars inserted beneath them at a later date (e.g. Lincoln and Brasenose in the 17th century). On one or both sides of the hall, near the dais-end, there were commonly projecting bay-windows called oriels, but occasionally these were added at a later date.

Kitchens, in whole or in part, mediæval, still survive at New College, Magdalen, Lincoln, Corpus Christi and Christ Church.

The evolution of the college-chapel plan at Oxford is a matter of considerable interest. The chapel must always have consisted of two parts, the chapel proper in which were the stalls of the members of the foundation, and the ante-chapel at the W. end, screened off and forming a vestibule. This is a plan which must have been adopted earlier in such of the smaller churches of some monastic orders, particularly nuns, where there was no admittance of the general laity. In the smaller college-chapels at Oxford these divisions were ritual only and the building formed a simple rectangular plan. In some instances, such as Lincoln, Exeter and Brasenose, these chapels (all now transformed or destroyed) were upon the first floor, but in other cases such as Balliol (re-built) and St. John's they were on the ground floor. The greater colleges, in the later middle ages, evolved a plan which was largely confined to Oxford and consisted of a choir or chancel with an ante-chapel at right-angles to it, in the form of a transept. The earliest example of this is the chapel at Merton where a complete cruciform church with a central tower and an aisled nave was projected, but the nave was never actually built and seems to have been definitely abandoned in the 15th century. The resultant plan was thus the typical Oxford chapeltype with the addition of a tower, produced fortuitously; it can probably never be decided if this was the determining factor in the production of the type. The next in date of these chapels is that at New College where an alteration in the course of building the great W. window may perhaps imply that an open arch and consequently a nave was, for a short period, in contemplation. If this were so it greatly strengthens the claim of Merton chapel to be the archetype. This form of chapel was repeated at All Souls, Magdalen and, by reason of a late addition, at Queen's (now destroyed). After the Reformation, it was reproduced at Oriel, Brasenose and Wadham. Outside Oxford an ante-chapel of the same type was built at Eton College in 1479, presumably under the influence of Waynflete. Only three colleges possess bell-towers, one standing over the crossing at Merton and the others separate structures standing on the town-wall at New College and on the street-front at Magdalen. The other college-chapels seem to have been content with bell-cotes.

Many chapels were built or re-built in the 17th century, including, besides those mentioned above, University, Lincoln, Trinity, Exeter (destroyed), Jesus and St. Edmund Hall. The chapel of Trinity is a purely Renaissance building, as is that at St. Edmund Hall. It seems probable that the design of the chapel at Lincoln was based on that of the 15th-century chapel at Trinity re-built in 1691–4.

The Library was almost universally on the first floor and commonly in one of the ranges of the main quadrangle. The earliest, however, at Merton and dating from 1371–9, was on two sides of a minor quadrangle, and the windows here, as elsewhere, are arranged to light the spaces between the book-cases. Later mediæval libraries survive at Trinity, Balliol, Magdalen and Corpus Christi and the old library at All Souls has been put to other uses. At Christ Church the monastic Frater became the first library and late in the 16th century the S. wing of St. John's Library was built, to be extended to an E. wing by Archbishop Laud. The 17th-century libraries at Wadham, Brasenose and Jesus may also be mentioned, together with the splendid late 17th-century library at Queen's, the 18th-century Codrington Library at All Souls and the nearly contemporary building at Christ Church.

The sets of chambers, in the later Middle Ages, consisted of a large sleeping or living room used in common by two, three or four persons and a small separate study for each individual, opening off it. Remains of this arrangement can be studied at New College and elsewhere.

The Gatehouse was an essential feature even if there was no formal quadrangle, as all the colleges were enclosed and the entrance was in charge of a porter. Most of the Oxford gatehouses have been extensively refaced or re-built, but mediæval structures survive in whole or in part at Magdalen (Founder's Tower), Brasenose, St. John's, All Souls, Merton, etc. The most ornate of these is the first named, which survives intact; the stone panelling on the gatehouse at Brasenose has been renewed. The great gate at Christ Church was only completed in 1681–2.

An occasional adjunct to a college was the cloister but the only independent structure of this type is at New College, where it was built as a cemetery. The cloister at Magdalen forms part of the main quadrangle and the small cloister at Corpus Christi was re-built early in the 18th century. The former cloister at All Souls has been destroyed and the projected cloister at Christ Church was never completed.

As may be gathered from the above the earlier post-Reformation collegiate buildings did not greatly differ either in form or purpose from those of the 15th century and the Queen's College is the only example in Oxford of completely Renaissance style and lay-out. The Canterbury Quadrangle at St. John's is more Renaissance than Tudor, but Peckwater Quadrangle at Christ Church is again purely Renaissance, as are the late 17th and 18th-century buildings at Worcester, Magdalen and Trinity.

The practice of providing Common Rooms for the fellows seems to have been begun at Cambridge (Trinity College) in the middle of the 17th century. The earliest Common Room at Oxford was introduced at Merton in 1661. Before the end of the century most of the colleges had been so provided and many of these rooms are fine examples of late 17th-century panelling.

The phenomenon of the survival of Gothic and semi-Gothic forms in the architecture of 17th-century Oxford has long been looked upon as symptomatic of the conservative and traditional outlook of the University in artistic matters. While it is true that these forms seem to have survived longer in Oxford than in any other important centre, yet it should also be remembered that Oxford is not an isolated example of this tendency. It would seem indeed that Gothic, in some form, was looked upon throughout England in the 16th and much of the 17th century as the appropriate style for church-building. It will be sufficient, in this connection, to cite such examples as the chapel at Staunton Harold (1653), the tower at Hillingdon (1629), and the churches re-built by the Lady Anne Clifford in Westmorland (1658–60), to show how general was the use of Gothic in church-building of the 17th century. So strong was this tradition that it seems to have induced if not compelled even Inigo Jones to the use of a modified Gothic at St. Catharine Cree, London (1628), and Sir Christopher Wren to design entirely Gothic structures such as St. Mary Aldermary (c. 1670), St. Alban Wood Street (1682–7) and the tower of St. Dunstan in the East (1670–1). This almost universal Gothic tradition seems to have been applied at Oxford to College building in general and not to churches and chapels alone, and with it was developed a taste for the more showy and eccentric features of Tudor Gothic such as the fan-vault. The vault of c. 1500 over the presbytery of the cathedral is not strictly speaking a fan-vault, but it may nevertheless have set the fashion for roofs of this character and forms indeed an obvious model for the combined wood and plaster ceiling at Brasenose chapel (1659). Fan-vaulting in stone is to be found at Wadham gatehouse (1610–13), the Schools gatehouse (1613), Oriel gatehouse (1620–22), the Convocation House, etc. (1634–7), University gatehouse (1635–7), Christ Church great staircase (c. 1640), Tom Tower (1682–3) and University, Radcliffe gatehouse (1716–19). Of these by far the most remarkable is the vault of the staircase at Christ Church which is more truly Gothic in character than any of the others. The early 18th-century example at University is in keeping with the Tudor character of the whole of the Radcliffe Quadrangle and, with part of the N. range at St. Edmund Hall, forms the latest expression of this tradition. The revival of Gothic in the 18th century had little or nothing in common with this tradition and Hawksmoor's quadrangle at All Souls is merely a professional architect's excursion into a foreign and little understood field. The Gothic tradition in 17th-century Oxford is further exemplified by a series of chapels and halls; of the former Wadham (1610–13), Lincoln (1629–31), Oriel (1637–42), University (begun 1637) and Brasenose (1656–9) still survive, but Exeter (1624) has been destroyed. It seems likely that the chapel at Lincoln was in part a copy of the 15th-century chapel at Trinity, destroyed at the close of the 17th century, and the chapel at Brasenose shows a freer introduction of Classical details than the others. The halls at Wadham, Oriel and University were designed with their accompanying chapels and the hall at Exeter (1618) is of similar general character.

One somewhat unusual departure from tradition must be mentioned here as occurring in three instances at Oxford. The S. side of the Fellows Quadrangle at Merton (1608–10) has a central feature with four of the Classical orders superimposed; this feature is repeated in a less accomplished manner in the Quadrangle at Wadham (1610–13) and all five orders are to be found on the inner face of the gate-tower of the School's Quadrangle (1635–7, refaced); the first and last of these are presumably the work of the Halifax masons to be mentioned later.

The gatehouses, of the period, are generally undistinguished forming part of an embattled tower rising a stage above the adjoining range; they follow the type of the 15th and early 16th-century gatehouses of St. John's, Brasenose and Corpus Christi but occasionally some Renaissance detail was introduced. The Renaissance gateway (1599) of St. Alban's Hall (Merton) is one of the few examples of Elizabethan decorative architecture in Oxford and the gatehouse at Pembroke (1673–94) had, before its restoration, a Renaissance front and this was advanced a stage further in the gatehouse of Exeter (1701–3) with its Palladian front and domed vault set in a range of traditional Tudor character; the front of this gatehouse perished in the restoration of 1883–4.

Perhaps the most pleasing of all the partially Renaissance buildings of Oxford is the Canterbury Quadrangle at St. John's (1631–6); its graceful loggias and ornate central features combine quite harmoniously with the Tudor windows of the upper storey.

With the advent at Oxford of the individual architect, in contradistinction to the working mason, the more or less pure Palladian style was introduced into the city in buildings not strictly ecclesiastical. Thus Inigo Jones built the isolated gatehouse (c. 1630) at Magdalen, destroyed in 1844, and Nicholas Stone designed the still-existing gateways of the Botanic Garden; he also designed the porch at St. Mary the Virgin (1637) with its concession to ecclesiastical tradition in its fan-vault. The work of Sir Christopher Wren at Oxford is at its lowest estimate considerable and his authorship of the designs of the Sheldonian Theatre (1664–9), of the range of the garden quadrangle at Trinity (1665) and of the completion of Tom Tower (1681–2) is unquestioned. The design of the Old Ashmolean Building (1679–83) has been ascribed to him but, apart from its general excellence, the evidence is against the ascription. The chapel at Trinity (1691–4) may well have been inspired by one of his designs though the extant correspondence shows that he did not actually act as the architect. In regard to Queen's the state ment, in his list of works, that he built the chapel here is certainly misleading; he may have been responsible for the design of the Library (1693–6) and possibly produced a general scheme for the rebuilding of the college, but the scheme adopted was in other hands. Nicholas Hawksmoor is generally accredited with the actual design of the college, which is much influenced by Vanbrugh under whom Hawksmoor worked at Blenheim (1710–15). Hawksmoor certainly designed the Old Clarendon Building (1711–13) and the N. quadrangle at All Souls (1714–15), already referred to. To Sir John Vanbrugh himself has been ascribed the front of the house No. 20 St. Michael's Street and to nearly the same period, but by another architect, belongs the Judge's Lodging (1702) in St. Giles. Among the architects of this age are to be found also two amateurs—Henry Aldrich (1647–1710), Dean of Christ Church, and Dr. George Clarke (1661– 1736), Fellow of All Souls and Member for Oxford. The former designed the new Peckwater Quadrangle (begun 1705) at Christ Church, the Fellows Buildings at Corpus Christi (begun 1706) and the church of All Saints (1707–8). Dr. Clarke's contribution is more doubtful but he is credited with the design of the New Library (begun 1716) at Christ Church, the new buildings at Worcester (begun 1720) and with other works at All Souls. Edward Holdsworth (1684–1746), another amateur, produced a design for a general rebuilding of the main quadrangle at Magdalen (illustrated in Williams' Oxonia), but of this only the N. range (begun in 1733) was completed and is now known as New Buildings. James Gibbs (1682–1754) designed the central feature of Oxford—the Radcliffe Camera (begun 1737)—and is credited also with the stone screen in the hall at St. John's (1742). Henry Keene (1726–76) was employed by Magdalen in 1750 and is said to have completed the N. side of the Quadrangle at Worcester. He designed the Anatomy School at Christ Church (1766), the Fisher Buildings at Balliol (1769) and the Radcliffe Infirmary and Observatory (1772). James Wyatt (1746–1813) designed the new buildings of the Canterbury Quadrangle at Christ Church (1773–8), before he had begun to adopt the Gothic convention. All these late 17th and 18th-century buildings illustrate the general phases of development of the later English Renaissance and if few of them are of outstanding merit, their general level is high and such structures as the Old Ashmolean, Queen's Library and the Radcliffe Camera stand in the first rank.

Craftsmen and Artists.

It is perhaps desirable to include here a short account of some of the more prominent craftsmen employed on the Oxford buildings from the 15th century onwards. It should, however, be understood that these notes do not profess to be in any way complete and do not depend on any original research into documentary sources.

Masons. The names of a certain number of mediæval masons have been preserved in the accounts of the Divinity School and of various colleges and elsewhere. Thus Richard Winchcomb and Thomas Elkyn were master-masons at the Divinity School in 1429 and 1439 respectively. The vault there (c. 1480) was probably the work of William Orchard, who was also master-mason at Magdalen in 1475 and worked at St. Bernard's College in 1502; he was buried at St. Frideswide. Richard Chevynton was master-mason at All Souls. William Raynold was the mason responsible for building the bell-tower at Magdalen. William Vertue and William Est were the master-masons for the building of Corpus Christi; the former was at that time the king's chief mason. The master-masons employed by Wolsey at Christ Church from 1525 to 1528 were John Lubbins and Thomas Redmayne.

There are numerous records of masons employed on the 17th-century college-buildings. Amongst the earliest of these are the partners John Akroyd (1556–1613), John Bentley (1574– 1615) and his brother Michael, who migrated from Halifax to Oxford, probably at the instigation of Sir Henry Savile; they were employed on the Fellows Quadrangle at Merton (1608–10) and on the Schools Quadrangle (begun 1610). Akroyd was buried in St. Mary's Church and Bentley at St. Peter in the East. Both their buildings make use of the superimposed Classical orders (four at Merton and five at the Schools) and the same motive was adopted at Wadham. Here, however, the master-mason seems to have been William Arnold who was succeeded in 1612 by Edmond Arnold, no doubt a relative. John Jackson (fl. 1634–63) was employed as master-mason on the Canterbury Quadrangle at St. John's (1634), the Selden End of Bodley (1634–7), the porch at St. Mary the Virgin (1637) and on Brasenose chapel (where he designed the ceiling) and library (1657–9); he was buried at St. Mary Magdalen. The vault of the staircase at Christ Church (c. 1640) was built by a certain Smith "artificer" of London who cannot be further identified. Sir Christopher Wren brought to Oxford a number of masons and craftsmen who had been employed by him elsewhere. Among these were Thomas Robinson, employed on the Sheldonian (1664–9), Thomas Strong, who owned the Taynton quarries, at Trinity and Christopher Kempster on Tom Tower at Christ Church. Thomas Wood was employed as mason on the Old Ashmolean and has been suggested as the author of the design. William Bird worked as a stone-carver on the Sheldonian and the same man or a namesake was the mason in charge of the Garden Quadrangle at New College (1682–3). If he is also to be identified with the William Bird who signs the Fettiplace monument (1657) in Swinbrook church, he was presumably of local extraction.

Carpenters and Joiners. Humphrey Coke, chief carpenter to the king 1519–31, built the roof of the hall at Corpus Christi and probably also the roof of the hall at Christ Church. Thomas Holt of York, master-carpenter, worked with the Halifax masons at Merton and the Schools Quadrangle and was also responsible for the carpentry at Wadham. He died in 1624 and was buried at St. Cross church, where his tombstone described him as architect of the "Public Schools." John Bolton was the joiner entrusted with the screens in the chapel and hall at Wadham. Chrysostome Parkes was employed as a carpenter at Brasenose in 1635–6. William Clere and Richard Clere were employed on the Sheldonian as joiner and wood-carver respectively; both of these worked also on Wren's city-churches as did also Jonathan Mayn, a wood-carver, who worked on the hall at Corpus Christi in 1700. Thomas Barker, joiner, made the reredos at University in 1694. The best known joiner and carver of this period at Oxford is, however, Arthur Frogley who, though he acted as master-carpenter at the Sheldonian was not one of Wren's craftsmen. He worked at Brasenose in 1678 and 1684, on the Common Room at Merton in 1680, on the chapel at St. Edmund Hall about 1682, on the Common Room at Lincoln in 1684 and on the Hall at Corpus Christi in 1700. Richard Frogley, no doubt a relative, was carpenter at the Old Ashmolean in 1679–83. The best known of all the wood-carvers of the period, Grinling Gibbons, is not certainly represented at Oxford, but the carving in the chapel at Trinity may be ascribed to him, not only by reason of its excellence but also from the fact that Miss Celia Fiennes (c. 1695) asserts that it was by the same hand as the carving she had seen at Windsor, on which, according to the extant accounts, Gibbons was certainly employed.

Sculptors. The carved figures and monuments at Oxford are not often to be ascribed to an individual artist until the 18th century. It is known, however, that John Blackshaw carved the figures at Wadham. Hubert le Sueur was the artist responsible for the bronze figures of Charles I and his queen in the Canterbury Quadrangle at St. John's and no doubt also for the bust of the king at the Bodleian Library. Nicholas Stone, according to his note-books produced the Bodley (Merton), Littleton (Magdalen) and Barker (New College) monuments, as well as the architectural works mentioned above; his son John produced the Banks monument in the cathedral. William Stanton, of London, executed the Holloway monument (1679) in St. Mary the Virgin; I. Latham signs the Grandison monument at the cathedral (after 1670), and a certain T. Hill signs the Levinz monument (1699) at St. John's. The figures on the tower at Trinity have been ascribed to Caius Gabriel Cibber and it is known that the series of figures on Queen's Library (1693–6) are from the hands of an artist named Vanderstine. Francis Bird worked for Wren at St. Paul's Cathedral and executed the figure of Wolsey on Tom Tower in 1719. Sir Henry Cheere designed the monuments of Dean Aldrich and Archbishop Boulter at the cathedral, executed statues at Queen's and in the Codrington Library at All Souls and is credited with figures on the Sheldonian and the Old Clarendon Building.

Monastic Buildings, etc.

The Cathedral with its adjoining structures is the only monastic building of any importance in Oxford. It was the church of a priory of Austin Canons and the chapter-house, frater and much of the cloister and dorter-range still survive. A subsidiary building, of uncertain purpose is all that remains of the rich Augustinian Abbey of Oseney and a stretch of wall with a doorway alone represents the Cistercian Abbey of Rewley. Of the houses of the four orders of Friars still less survives; a few fragments may be assigned to the Franciscan house but of the Dominican, Carmelite and Austin houses there are no recognisable remains. Outside the city, some walls and ruined buildings now represent the Benedictine nunnery of Godstow.

Of the various monastic colleges, existing in the later Middle Ages, there are still some remains. Durham and Gloucester Colleges are represented by some of the buildings of Trinity and Worcester. Both these were Benedictine foundations as was Canterbury College, now replaced by the late 18th-century Canterbury Quadrangle at Christ Church. The Cistercian College of St. Bernard was substantially the existing main quadrangle at St. John's and the Augustinian College of St. Mary is represented by parts of Frewin Hall and its gatehouse. None of these buildings seem to have differed greatly from the ordinary college-plan except Gloucester College where the various Benedictine houses had each a separate camera, built at its own expense.

Of the minor religious houses, there are some remains of the hospital of St. John the Baptist incorporated in the buildings of Magdalen. The hospital of St. Bartholomew at Cowley is represented by its 14th-century chapel and by a range of buildings, presumably almshouses, erected by Oriel College in 1649. In St. Clement's Street is the block of almshouses founded by William Stone in 1700.

Secular Buildings.

There are few remains of mediæval domestic architecture in Oxford apart from the colleges. The three crypts with ribbed vaulting have already been referred to and there are numerous other stone-built cellars which may also be mediæval but are quite featureless. Though forming part of Merton College, the small two-bay hall of stone incorporated in the N. range of the Front Quadrangle, may be mentioned here as being a purely domestic hall, perhaps that of the Warden's Lodging built in 1299–1300; the original and unusual roof with queen-posts still survives. A 13th-century building also survives at Iffley Rectory. There are some remains of the hall of Tackley's Inn at Nos. 106–107 High Street, built early in the 14th century; it was a stone building and one of the original windows still exists. Other stone-built mediæval houses survive in part at Beam Hall and No. 26 Ship Street; the latter retains a 15th-century doorway and an oak window of the same date. Several houses retain evidence of 15th-century timber-construction but the only surviving structure at all complete is the N. range of the Golden Cross Hotel.

The principal examples of 16th and 17th-century architecture are mostly timber-framed and of these Kemp Hall, the Old Palace and No. 126 High Street may be mentioned. The N. front of the Old Palace is a handsome example of early 17th-century work with projecting stories and oriel-windows; the front of No. 126 High Street masks a 15th-century building. The house, formerly Littlemore Hall, in St. Aldate's is an early 17th-century building of stone, which, though altered, retains much of its original appearance. The houses in Holywell Street, though none of them of any great individual distinction, give a pleasing character to the whole street. Various other houses of this period have internal features, generally plasterwork, of considerable interest; these features are dealt with elsewhere.

The outstanding examples of early 18th-century design have already been referred to. The front of Vanbrugh House is ascribed to Sir John Vanbrugh but the architect of the Judge's Lodging is unknown. Owing to the perished condition of the stone-surface it has had to be largely refaced quite recently.

Fittings.

Bells: The earliest bell in the district is the second at St. Clement's church which seems to date from early in the 14th century but is uninscribed. The two bells at the cathedral dedicated to St. John and St. Mary are of c. 1400 and from a London foundry; they with the great bell in Tom Tower came from Oseney Abbey but the great bell has been recast. The seventh bell at Magdalen is by William Dawe and the fifth at Headington by John Danyell; both date from the 15th century. Of the 17th-century founders those best represented are Ellis Knight with 9 bells, Richard Keene with 16, and Michael Darbie with 8. Henry Knight has four and Newcombe of Leicester two, one of which is the curious music-bell, at St. Mary the Virgin, of 1612. The largest bell in Oxford is Great Tom at Christ Church, formerly at Oseney Abbey and re-cast by Christopher Hodson in 1680. Abraham Rudhall was responsible for a considerable number of bells at the end of the 17th and in the early part of the 18th century.

Brasses: The Oxford colleges are comparatively rich in monumental brasses, particularly New College and Merton. At the latter is the earliest brass in Oxford, that of Richard de Hakeborne, 1310, with a figure of a priest in the head of a cross; another mutilated brass of similar character, in the same college, dates from c. 1370. The other brasses with figures are all of the 15th century or later. The brass of two priests on a bracket and with a canopy, c. 1420, and the fine figure in an enriched cope of Henry Sever, Warden, 1471, are both at Merton. At New College is a long series of Wardens and fellows, mostly in academic costume; the earliest is to Richard Malford, Warden; the brass of Thomas Cranley, Archbishop of Dublin, 1417, and of John Young, Bishop of Callipolis, 1526, are important examples of episcopal figures in mass-vestments; the archbishop stands under a canopy. The earlier brasses at Queen's have been much defaced; they include a figure in a cope of Robert Langton, 1524. The earliest brass in the cathedral is a figure of Edward Courtenay, c. 1450, in civil dress. The brass of Henry Dow 1578, is a palimpsest; on the back of the figure is the head of a man and on that of the inscription, a figure in tabernacle-work. The only later brasses which need be mentioned are the figure in a shroud at Corpus Christi (1537) and the remarkable mural plates with elaborate allegorical subjects of Henry Robinson and Henry Airay, both 1616, at Queen's.

Chests: The church-chests of Oxford include a much restored example of c. 1300 at St. Mary Magdalen, with carving cut out of the solid. There are iron-bound chests of more ordinary type at St. Michael and St. Peter le Bailey. Attention may be called here to a number of highly important chests belonging to colleges. It has not been the custom of the Commission to include articles of movable furniture, except in churches, but some reference seems desirable to the chest with late 13th or early 14th-century ironwork in Merton Library, the splendid carved chest with scenes from the battle of Courtrai at New College and the 14th-century chest in the Smoking Room at Magdalen.

Communion Rails and Tables: There are enriched 17th-century communion-rails in the collegechapels of Lincoln, Oriel and Wadham. The enriched wooden rails at Trinity date from c. 1694 and the wrought-iron rails at Queen's from early in the 18th century. The only Communion Table that need be mentioned is one of c. 1600 with enriched bulbous legs, from Ilminster, now in Wadham Chapel.

Doors: A very fine door with rich late 13th-century ironwork has been preserved in the re-built hall at Merton. A second 13th-century door with ironwork survives at St. Thomas the Martyr. There are panelled 15th-century doors, more or less enriched, in the gatehouses of Merton and St. John's and in the Founder's tower at Magdalen; a fourth has been re-set in the W. range at Balliol. To the early part of the 16th century belong the doors in the gatehouses of Brasenose, Christ Church and Corpus Christi. The 17th-century doors in the gatehouse at Hertford and the elaborate doors in the gateway of the Schools Quadrangle at the Bodleian should also be noticed. There are enriched doors of minor importance in the Garden entrance at St. John's, in the Library at the same college, in the Library at Balliol and elsewhere.

Fireplaces and Overmantels: There are throughout Oxford numerous examples of stone fireplaces of the usual Tudor type, with four-centred arches in square heads; this type survived far into the 17th-century as did so many other Tudor features. In a number of later examples the mouldings of the arch are returned at right angles half way down the jambs. Many fireplaces are provided with elaborate oak overmantels, commonly supported on pilasters or columns flanking the opening. The earliest of these date from late in the 16th century and the type continues through the first half of the following century. The arched motive is a favourite one and heraldic carvings are frequent; occasionally there are figure subjects as in the series of fables at University. The best examples of this period in the colleges are to be found in the room over the gate at Corpus Christi (late 16th-century), in the corresponding room at Oriel (1622), in the Principal's Lodging at Jesus, in several rooms at All Souls, the Junior Common Room at Corpus Christi and in the President's Lodgings at St. John's. The overmantel of 1575 in the Senior Common Room at University came from a demolished house in High Street and the early 17th-century overmantel in the Master's Lodging at Pembroke came from No. 3 Brewer Street. Examples in private houses may be mentioned at Beam Hall, Postmaster's Hall, Frewin Hall, 90 High Street and Church Farm Wolvercote. Many of the Senior Common Rooms have fireplaces and panelled overmantels of late 17th-century date, sometimes with carved enrichments; the example at Wadham is of similar character but seems to date from 1724–5. The carved overmantel of c. 1700 at the Greyfriars may also be mentioned.

Fonts: There are 12th and 13th-century fonts of simple design at Binsey, Cowley, Iffley and Wolvercote; the Iffley font has a square bowl and five supporting shafts, but the others are all three cylindrical. The 13th-century font at St. Giles is of more elaborate type, with dog-tooth ornament. To the following century belong the fonts at St. Mary Magdalen, with elaborate panelling, and All Saints (from St. Martin Carfax), with carved figures. The 15th-century font at St. Aldate's has a 17th-century pyramidal cover, painted with scenes of the Exodus.

Glass: From the end of the 13th century onwards Oxford provides perhaps the most complete and consecutive series of glass-paintings of any place in the country. This is particu larly so in regard to the 17th and 18th centuries, in which regard Oxford stands alone. The earliest glass in the city is the group of late 13th-century figures in St. Michael's church, but to the end of the same or the beginning of the next century belongs the largely intact glass in Merton Chapel; the rich tracery-glass in St. Lucy's chapel, and the glass in the N. windows of the Latin Chapel, both in the cathedral, belong to the first half of the 14th century. To the close of the 14th century belong the fine series of windows in the ante-chapel of New College and remains of the windows in the chapel itself. The 15th century, again, is well-represented. At All Souls ante-chapel is a series of figures of saints and a second series of kings and bishops, formerly in the Library; the Library at Trinity retains also a series of figures with heraldry and Merton chapel has some fine figures in the E. window and small figures in the tracery of the W. window. There are remains of glass of the same period in the church of St. Peter in the East. Glass of the first half of the 16th century is mainly represented at Balliol and Queen's. At the former the E. window dates from 1529 and the S.E. window with scenes of the martyrdom of St. Catherine from about the same period. At Queen's the early 16th-century glass from the former antechapel was re-arranged, restored and re-set early in the 18th century. The delicately enriched initials at Christ Church Chapter House should also be noticed.

With the first half of the 17th century an important revival of glass-painting took place which is chiefly represented in Oxford. The most prolific artists were the two van Linges, Bernard and Abraham; they belonged to a family of glass-painters at Emden. Bernard designed and executed the E. window at Wadham in 1622–3 and the side windows at Lincoln, 1629–30, are certainly his work, as in several instances they duplicate his figures at Lincoln's Inn Chapel, London, dated and signed 1623–4; the same applies to the figure of Bishop King in the cathedral where the background is duplicated in Lincoln's Inn Chapel. Abraham van Linge was responsible for glass of a distinctly different type with landscape and other backgrounds; he executed windows at Queen's in 1635, Balliol in 1637, Christ Church in the same decade and at University in 1641; all this glass survives in whole or in part. To the same period belongs the fine E. window at Lincoln (1629). The much inferior glass in the side windows at Wadham is rather earlier, that on the N. being of 1613–14 and that on the S. of 1616; the N. windows are ascribed to Robert Rudland of Oxford. Probably of the second quarter of the 17th century is the E. window of St. Peter in the East, which may have been brought from elsewhere. The windows in chiaroscuro in the ante-chapel at Magdalen are ascribed to Richard Greenbury who supplied glass to the chapel in 1632.

After the Restoration Henry Gyles (1640–1709) of York, his pupil William Price Sen. (d. 1722) and Joshua Price (d. 1717) his brother, worked at Oxford. The first produced the Nativity in the E. window at University (1687), of which some fragments survive. William Price glazed the E. windows of the Cathedral (1696) and Merton (1711–2); of the cathedral window some fragments have been preserved in the transept clearstorey; the Merton window has been removed from its place but is still extant. Joshua Price repaired and re-set the earlier glass at Queen's (1715–17) and himself produced the E. window there; he also repaired the van Linge windows at the cathedral. John Oliver (1616–1700) of London produced glass for the cathedral which has not survived. William Price Jun. (d. 1765), son of Joshua Price, executed the S. windows at New College in 1735–40. William Peckett, who worked extensively on the glass at York Minster, was employed (1765) on the windows on the N. side of New College; he also executed the Presentation in the Temple (1767) at Oriel. James Pearson produced the Christ and the four Evangelists (1776) now in the W. window at Brasenose. It remains to mention the W. window at New College, executed by Thomas Jarvis (1778–85) from the designs of Sir Joshua Reynolds and the renewal of the W. window at Magdalen by Francis Eginton in 1794.

Heraldic glass is common in many of the colleges, beginning with the 14th-century shields at Merton and Christ Church, and followed by 15th-century heraldry at Balliol, Trinity, etc., and later work in various colleges. A considerable amount of foreign glass has been installed in the Bodleian Library, at Merton, Magdalen and Trinity and in St. Mary Magdalen church.

Lecterns: The college-chapels of Oxford have an interesting series of brass lecterns, the earliest of which at Merton of c. 1500 has a gabled book-rest. All the rest are of the more usual eagle-type and, except for the early 16th-century example at Corpus Christi, are all of the 17th century. These are to be found at Magdalen (1633), Balliol (c. 1635), Exeter (1637), Queen's (1653), Oriel (1654) and Wadham (1691). The brass lectern with a gable book-rest at Jesus was given by John Brickdale in 1716–17.

Libraries: A considerable number of the college libraries of Oxford retain their ancient fittings. Of these a part of the presses at Corpus Christi date apparently from 1517. The presses in the W. wing at Merton are of uncertain date but those in the E. wing were copied from them in 1623. The fittings of the W. wing at St. John's date from 1596 when the old library was built. Duke Humphrey's Library was refitted by Sir Thomas Bodley in 1598–1600 and he added the Arts End in 1610–12, which possesses the earliest English example of the wall-system with a gallery. The fittings of the library at Jesus date from c. 1623 and were refixed in the present building in 1679. The presses, etc., at Trinity, were made about 1625. To the end of the century (1694) belong the library-fittings of Queen's. The 18th-century Codrington Library at All Souls and the new libraries at Christ Church and Oriel may also be mentioned. A detailed study of the earlier libraries has been made by Canon B. H. Streeter in The Chained Library (1931).

Monuments: The earliest surviving memorials in Oxford are the broken 11th-century slabs in the Ashmolean Museum and the slab with a face at the cathedral; the last has some affinities with the carvings of the capitals in the castle crypt and may thus be of late 11th-century date. To the 13th century belong the remains of the finely carved shrine-base of St. Frideswide (1289) and an ornamental slab, of 1297, brought from Oseney Abbey; both are in the cathedral. Five monuments with mediæval effigies survive in Oxford; of these three are at the cathedral and include the fine canopied tomb ascribed to Prior Sutton, 1316, and the monument of Lady Furnival, 1354; the monument of Richard Patten, c. 1450, father of the founder, was brought to Magdalen from the church of All Saints Wainfleet; the tomb and effigy of John Noble, 1522, at St. Aldate's completes the list. The elaborate tomb and chapel called the Watching-loft at the cathedral should also be mentioned as should the late Gothic monument of Bishop King, 1557, in the same building; it is a Purbeck marble structure of a well-known London type. To the middle of the century (1559) belongs the beautiful monument of Sir Thomas Pope and one of his wives at Trinity; owing to its enclosure its details are not readily seen. The more ordinary Elizabethan and Jacobean monuments are represented by a long series of altar-tombs, wall-monuments and tablets; of the first class may be mentioned those of William Levinz, 1616 (All Saints Church), Sir John Walter, 1630 (Wolvercote Church), and the lofty monument of Sir John Portman, 1634 (Wadham); the best wall-monuments include Lawrence Humphrey, 1590 (Magdalen), Sir Thomas Bodley 1613 (Merton), Sir Henry Savile, 1622 (Merton), Sir William Langton, 1626 (Magdalen), Sir Eubule Thelwall, 1630 (Jesus), and Sir William Paddy, 1634 (St. John's); of the smaller tablets mentioned should be made of those commemorating Sir Thomas Bodley (1605) and Charles I (1636) in the Bodleian Library, and that of Robert Burton, 1639, in the cathedral. The monument of Sir Thomas Bodley at Merton is a work of Nicholas Stone, who is also represented at Oxford by the Littleton monument (1635) at Magdalen and the Barker monument (1632) at New College. His son John Stone produced the Banks monument (1644) in the cathedral.

Post-Restoration memorials are commonly less important but there is a fine monument to Richard Baylie, 1667, at St. John's and a very considerable number of well-executed tablets.

Paintings: The mediæval paintings in the cathedral are mostly much faded and damaged. The 14th-century censing angels on the vault of the Lady Chapel are, however, still apparent as are other angels at the E. end of the S. aisle of the presbytery. In the chapter-house is a series of 13th-century roundels with figures, those towards the E. being fairly well preserved.

Painted domestic wall-decoration is best represented in the well-preserved painted room at No. 3 Cornmarket Street; here there are some remains of late mediæval decoration but the main scheme is of mid to late 16th-century date. There are some remains of later wall-decoration at Brasenose, St. Edmund Hall, St. John's, Merton library and elsewhere.

The allegorical painted ceiling of the Sheldonian Theatre was executed by Robert Streater, Serjeant-painter to Charles II. The main panel of the ceiling of the chapel at Trinity encloses a painting of the Ascension by Pierre Berchet (d. 1720).

Panelling: Linen-fold panelling of the first half of the 16th century is used in the halls of Magdalen and New Colleges. At the former are carved friezes and a series of admirably carved panels with figure subjects; the panelling at New College also has carved panels with heraldic and conventional decoration and at the top of the panelling at the dais-end is a vaulted cove and cresting. Of 17th-century panelling there are numerous examples, of which the Drawing Room of the Principal's Lodging at Jesus is perhaps the finest example. Panelling in Merton Library, Beam Hall and 13–14 Pembroke Street may also be mentioned. The series of late 17th-century Common Rooms provide good examples of panelling of that period and the Delegates' Room in the Old Clarendon Building is a handsome panelled apartment of the beginning of the 18th century.

Plasterwork: Oxford is very rich in plasterwork, both in the colleges and in private houses. The most ingenious and elaborate example is the fan-vault adapted to the hammer-beam roof in Brasenose chapel in 1659. The enriched barrel-ceiling of the Old Library at All Souls was erected in 1598 and is a very pleasing example of the period. Of late 17th or early 18th-century date are the main ceilings of Trinity Chapel (c. 1694), Queen's Library (1696) and All Saints Church (1708).

Amongst the ceilings of rooms of ordinary size those over the gates of Oriel (early 17th-century) and Corpus Christi (c. 1570–80) are perhaps the best examples of Elizabethan work. Of the examples of late 16th and early 17th-century work in private houses, the most important are at 82–3 St. Aldate's, Frewin Hall, the Old Palace St. Aldate's, 2 Brewer Street, Nos. 86–7, 90 and 104 High Street and Iffley Rectory. Late 17th or early 18th-century ceilings are represented in some Common Rooms, in the Greyfriars and in the Judge's Lodging. The elaborate plastered beam and cresting in the Library at Corpus Christi deserves a mention and there is plaster-decoration on the end walls of the Library at Merton.

Piscinæ: In the few churches dealt with in the present volume, there are few piscinæ of interest. The best are the 13th-century examples in St. Michael, the Lady Chapel at the cathedral and at Iffley. There is an enriched 14th-century piscina in the S. aisle of the presbytery of the cathedral and a canopied recess of the same century at St. Mary the Virgin.

Plate: It has not been thought desirable to include in this Inventory any account of the private plate of the Oxford colleges. This, though both extensive and of the highest interest and importance, has been exhaustively dealt with in the literature of the subject and would seem to come into the same category as the plate of the London City Companies which also was judged to be outside the purview of the Commission.

Of the church-plate of Oxford city the earliest piece is the Edwardian cup and cover-paten of 1551 from St. Clement. This is a highly unusual survival and the bowl is decorated with incised ornament similar to that on Elizabethan cups. There are cups of the usual Elizabethan type at St. Michael (1562), St. Cross (1569), St. Peter in the East (1569), St. Ebbe (1569) and All Saints (1597); a cup of the same general type at St. Peter in the East, appears to date from 1626. The splendid set of communion plate, given by Dr. John Fell to the cathedral in 1661, is decorated with elaborate repoussé work. The two vergers' staves may also be noted.

Pulpits: The finest pulpit in Oxford is the elaborately carved early 17th-century example with a sounding-board at the cathedral. All Saints church has a good early 18th-century pulpit also with a sounding-board. The college-chapels produced a particular type of pulpit, generally polygonal and standing on short legs with stretchers and easily movable. Nearly all of these date from the first half of the 17th century and may be seen at Brasenose, Corpus Christi, Jesus and Wadham; the example at Balliol is of more substantial form and both it and the square pulpit at Lincoln have lost their bases. The early 18th-century pulpit at Merton is of the traditional form but the 17th-century example at Wadham stands on a central stem.

In this section it is necessary to note the external stone pulpit of the 15th-century at Magdalen, a feature which it would be difficult to parallel elsewhere in this country.

Reredoses: The great reredoses, with numerous tiers of niches and figures, in the chapels of New College, All Souls and Magdalen are in great part modern restorations; the reredos at All Souls, however, retains considerable portions of original work in the backs of the niches and their vaults; New College reredos is almost entirely a restoration based on remains found at the restoration of the chapel, but the figure subjects from above the altar have been preserved in the vestry; the reredos at Magdalen seems to be entirely modern. The late 17th-century wooden reredos at Trinity is remarkable for the extraordinary delicacy of its carved ornament. The reredos at All Saints church was given in 1717.

Screens: The great majority of the Oxford screens are to be found in the chapels and halls of the colleges. Purely ecclesiastical screens are very infrequent. There are some remains of the curious stone Tudor screens inserted in the transept-arches of the cathedral and removed in one of the restorations; these remains are now to be found in one of the canons' gardens. The little chapel of St. Bartholomew Cowley has a chancel-screen of 1651.

The screens of the college-chapels belong most frequently to the second and third quarters of the 17th century; they are often richly carved and frequently have two canopied stalls against the E. face for the head of the college and his deputy. Such screens survive at Lincoln (without canopies), Oriel and Wadham; the screen from Exeter is now in the church of Long Wittenham, Berks.; the rather later screens at Brasenose, Corpus Christi, Jesus, St. Edmund Hall and University are of the same general character. The screens at All Souls, Trinity and Queen's are of more strictly classical form; the first was given in 1664 and the second, of c. 1694, has elaborate and delicate carving similar to that on the reredos; the early 18th-century screen at Queen's is a severely classical composition.

The screens of the college-halls commonly have two doorways to the screens-passage and a gallery over. The early 16th-century screen at New College is formed of linen-fold panelling. To the first half of the 17th century belong the screens at Exeter, Jesus, Magdalen and Wadham. The screens at Lincoln and Corpus Christi date from c. 1700. Mention should also be made to the stone screen of 1742 at St. John's, ascribed to James Gibbs. There are screens of late 16th-century date and of c. 1623 in the two wings of the library at Merton.

Sedilia: The late 13th-century sedilia at Iffley Church and the 15th-century sedilia at St. Mary the Virgin are worthy of notice and there are remains of the 15th-century sedilia at All Souls and of the early 16th-century sedile in the chapel at Corpus Christi.

Staircases: The earlier staircases in the Oxford colleges are generally featureless, being straight flights between timber-framed walls. With the first half of the 17th century there begins a series of fine staircases of oak with ornamental features. To this period belong the staircases in the Schools Quadrangle at the Bodleian (c. 1620), in the Old Warden's Lodging at Merton (c. 1630), in the Provost's Lodging at Oriel (c. 1640), in the Master's Lodging at Pembroke, and in the President's Lodgings at St. John's. There are staircases of similar character at Kemp Hall (c. 1637) and Nos. 13–14 Pembroke Street (1641). The actual great staircase at the end of the hall at Christ Church has been re-built but the enclosing building with its 17th-century vault survives.

Of the later 17th and early 18th-century there are many examples; the best of these are to be found at the Old Ashmolean Building (c. 1680), leading to the Library at Jesus, at Queen's (c. 1696), at the Judge's Lodging St. Giles Street (c. 1702), at Greyfriars (c. 1700) and at 41 St. Giles Street (c. 1700).

Stalls: Oxford is particularly rich in stalls and stall-work, five churches and chapels having mediæval fittings of this type. The surviving stalls at the cathedral are in the Latin Chapel and include two misericordes of the 14th century and some richly carved early 16th-century popeyheads. The stalls at New College have a long series of admirably carved late 14th-century misericordes, some of which are of great elaboration and delicacy. The corresponding 15th-century series at All Souls and Magdalen are of inferior merit and execution but are nevertheless of considerable interest. The stalls at the church of St. Mary the Virgin are of more ordinary character but retain their panelled backings and desks. Stall-work of the 17th century is also of very frequent occurrence and of a more standardised type, with enriched panelled backings against the side walls. Perhaps the earliest are the stalls at Wadham of c. 1613; those at Lincoln of c. 1630, have simply carved misericordes in the mediæval tradition; here also a second range of stalls has been added late in the 17th century with a series of well-carved figures on the deskends. Stalls of the 17th century are also to be seen at Oriel, Brasenose, Corpus Christi, and St. Edmund Hall. To the end of the 17th century belong the stalls at University and Trinity and those at Queen's to the early part of the 18th century.

c—(381