An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the Town of Stamford. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1977.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Sectional Preface: Special Purpose Buildings', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the Town of Stamford(London, 1977), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/stamford/lix-lxiv [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Sectional Preface: Special Purpose Buildings', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the Town of Stamford(London, 1977), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/stamford/lix-lxiv.

"Sectional Preface: Special Purpose Buildings". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in the Town of Stamford. (London, 1977), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/stamford/lix-lxiv.

In this section

Almshouses

The earliest surviving almshouse building in Stamford is Browne's Hospital (48), established and built in 1475; the plan is derived from earlier medieval hospitals which had a single large room with cubicles for the inmates along the sides, and a chapel projecting from one end. At Browne's Hospital the main block includes the chapel but otherwise is of two storeys, with cubicles in a low poorly-lit ground-floor room. The first floor is occupied by the Audit Room, known as the Great Chamber in the 17th century (inventory of 1677 in hospital archives). The magnificence of this room invites speculation as to whether it was intended to have a public use. Comparison may be made with buildings such as St. Saviour's Hospital, Wells, built shortly after 1424 by Bishop Bubwith's executors, with a hall used as a town hall at the W. end (J. Parker, Architectural Antiquities of the City of Wells (1866), 69–70). In 1731 the small rooms were furnished with a bed, a shelf, a candlestick and extinguisher; by 1766 most had acquired a second shelf and a cupboard (inventories in hospital archives).

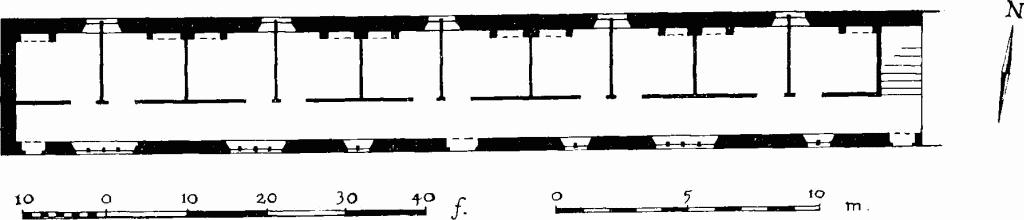

Fig. 9 (49) Lord Burghley's Hospital

Reconstruction of plan of range of c. 1616.

Lord Burghley's Hospital (49) is a rehabilitation of an older decayed establishment; the new range of lodgings probably built in 1616 survives much altered. Originally there was on the ground floor a long corridor with ten rooms opening off it (Fig. 9). This feature of an internal passage giving access to the rooms is found only occasionally in almshouses, a nearby example being the Maison Dieu at Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, of 1640. An open cloister, such as those of the 16th and 18th centuries at Abingdon, is more common. The upper floor at Burghley Hospital is a semi-attic, and was presumably used as a long gallery for indoor exercise.

All the remaining buildings follow the normal post-medieval pattern of single-room lodgings each entered from outside. Two, Fryer's and Truesdale's Hospitals (50, 53), share the distinction of having been designed by Basevi, while Snowden's (52) was designed by Pierce, a local man. Corporation Buildings (422), a municipal scheme for housing the poor of the town in 1795, was a double row of single-room dwellings. Williamson's Almshouse (398) was established in 1762 in an existing house, extra rooms being provided in a narrow wing built on the back; the plan resembled a pair of houses and each inmate may have had two rooms.

Hopkins' Almshouse (51) is of two storeys, with access to the first-floor rooms from an open terrace at the rear, an arrangement recalling that at Cobbs Well, Fowey, of c. 1700 (RCHM, Monuments Threatened or Destroyed (1963), p. 28). St. Peter's Callis, rebuilt in 1863, was in the early 19th century a building with lodgings on two storeys, the upper reached by an external stone staircase and a covered timber gallery on the rear or S. elevation (Stamford Report 2, 53).

Most of the almshouses were rebuilt in the early 19th century in the revived Gothic style; Hopkins' Almshouse of c. 1770 was the earliest in this style which was perhaps chosen in this instance because of the proximity of the medieval town gate which was destroyed at the time the almshouses were built.

Inns and Public Houses

Standing on the Great North Road half-way between London and York, Stamford had a large number of inns from the Middle Ages onwards. A 'great in called Kyngesin' is mentioned in 1388 (Cal. Inq. Misc. v. (1387–93) no. 93) probably in St. Mary's Hill. The Angel, later George and Angel, 13–14 St. Mary's Street (350), is mentioned in 1458 (Peck XIV, 47) and was part of the endowment of Browne's Hospital. The Blue Bell (243) was rebuilt shortly before 1595, but within a hundred years had declined greatly and was sub-divided into small tenements. All the earlier inns were built with courtyards which survive to a greater or lesser degree at the George (239), George and Angel (350), Blue Bell (243), Black Bull (352), Eagle and Child (355); smaller hostelries simply had a yard behind the street frontage, as at the Bull and Swan (216), and Coach and Horses (209), with stables and other outbuildings arranged informally. A large entry for the passage of wheeled vehicles was an essential feature of the larger inns.

Of the early inns, only the George remains (239). Built in the early 17th century, it consists of four rooms flanking an open entrance passage, and two stair turrets at the rear. The ground-floor rooms included a kitchen and a dining room; on the upper floors were lodging rooms but the circulation system is not easily reconstructed. Probably an access linked the stair turrets across the W. front, and the E. rooms were reached by short passages leading from it (Fig. 132). Galleried ranges of uncertain date flanked the yard, and were replaced in the 18th century. The new N. range had lodging rooms reached from a central stair and apparently by a corridor along the rear wall.

The Black Bull was almost completely rebuilt as the Stamford Hotel in 1810 (352), but inventories allow the arrangement of rooms to be reconstructed (LAO, 116/173 (of 1614); 131/407 (of 1626); 36/501 (of 1630); 17/115 (of 1674)). The lodgings were on two storeys, in pairs on either side of staircases; possibly there was no gallery. The Stamford Hotel was not originally an inn but a centre of social and political activity, and only became a commercial concern in 1828.

Built in the mid 18th century, the former Globe, 8 High Street (174), has recently been gutted. It is known to have had a bar, kitchen and large dining room on the ground floor, and 14 bedrooms on the two upper floors, reached from the staircase by a long passage (Mercury, 21 July 1768). Smaller hostelries of the late 18th and early 19th centuries resemble the more substantial small houses of the period. The Salutation (16 All Saints' Street (80), late 18th-century) and Coach and Horses (19 High Street St. Martins (209), partially rebuilt 1798) are basically class 9 houses. The Salutation had a bar and two tap rooms on one side of the hallway and private rooms on the other, with bedrooms on the first floor (1845 Survey, Browne's Hospital Archives). Public houses and ale houses were usually dwelling houses which, like the Carpenter's Arms (54 St. Leonard's Street (326)) had one front parlour converted into a public bar. The house of Sarah Kidington, victualler, contained in 1738 a great room with closets, presumably drinking booths (LAO, 210/30). The Balloon (6 Blackfriars Street (125)) is an example of a building intended from the start to be a public house; it had a parlour and a bar at the front, a kitchen behind, and dining-room and bedrooms on the upper floors (Mercury, 28 Dec. 1827).

Shops

The first documentary reference to a shop in Stamford is in the early 13th century (PRO, E 315/44, p. 39). Like many of the shops described in medieval documents, this was a small building consisting of a cellar, a shop and a solar and is similar to one mentioned later in St. Martin's parish (PRO, E 315/32, p. 21). A building lease in 1434 of an empty plot in St. Mary's parish specifies no more than a shop with a solar above (PRO, E 315/31, p. 3). A larger building is described in a draft building lease of 1484, as having a hall, shop, two chambers, and a kitchen at the back (Ex. MS, 53/4).

The most important medieval shop to survive is the undercroft at 13 St. Mary's Hill (338), which has steps leading down from street level through a door flanked by windows into a part-underground vaulted room of high quality. The remaining undercrofts include two (23 High Street (183) and 4 St. Mary's Place (342)) which have doors leading to the street; in 23 High Street, this may have originally been the only access. Both of these could have served as shops although that at 4 St. Mary's Place was beneath a guildhall. Other undercrofts and cellars referred to in medieval documents (see Cellars, above) may also have been shops. As early as the Middle Ages buildings in Stamford were sub-divided into shops and tenements in separate occupation. Some time before 1362 John Absolom gave the guild of St. Mary a cellar beneath Peter Wisbech's solar (PRO, C 41/174; Cal. Pat. 1361–4, 227). Four shops below one solar, apparently in Red Lion Square, were clearly all separately occupied in 1235. (Cal. Chart. 1226–57, p. 205).

In the 17th and 18th centuries most shops were simply one room on the ground floor of a house, distinguished by a more generous provision of windows. At 14 and 15 High Street (178, 179) window-openings on the ground floor had a rebate and a hollow-moulding; occupying the full width of the tene ment, they had low sills, and lintels almost at ceiling level. No. 55 High Street (191) had windows with low sills and ovolo-moulded jambs which also appear to have occupied the full width of the room (Fig. 110). Similar ovolo-moulded jambs with sills 2½ ft. above floor-level were observed at both 18 and 19 High Street (180) of c. 1720.

In 1775 the plans for rebuilding 15 St. Mary's Street (351) (Fig. 173) show the shop as a heated room with two closely-placed windows. A similar arrangement of two windows, but here apparently separated by a door, formerly existed in the E. room of 1 Red Lion Street (283), built in 1793. Perhaps the early 18th-century High Street shops had several closely-placed windows in this fashion. The front room of 25 Broad Street (139) was apparently designed for use as a shop or office, with a central door flanked by windows, and a separate side entrance to the house (Fig. 95). The interiors of all early shops have been altered, but an inventory made in 1721 of fittings in the house in High Street leased by John Spencer, mercer, included in the shop two sashes (i.e. removable windows), counters, drawers, wainscot and the inner door (LAO, LD 40/52).

During the 19th century shops in the centre of the town grew progressively larger, and began to encroach deeper into the building. The drapery shop built by Edward Thorpe at 3 High Street c. 1823 had a shop and counting house occupying the whole ground floor and a three-storey warehouse behind, the living quarters being mainly above the shop (172) (Fig. 101). The two modest shops at 50–51 Broad Street (149) have a small front room for a shop and a larger living room behind. No. 6 Ironmonger Street (244) is a larger building with a shop fitted with cupboards on the ground floor, and a kitchen behind, the remainder of the living accommodation being on the upper floor. At 21 High Street (182) the shop was probably confined to the S. room before 1836 when the present shop front was installed (Mercury, 17 Feb. 1815, 6 May 1836) and the shop extended to occupy the whole of the ground floor.

In the late 18th and early 19th century several shop fronts of impressive design were put up. That at 18–19 High Street (180), perhaps installed by the chemist Mills, was the most splendid before its recent mutilation; it consisted of a series of fluted Corinthian columns supporting an entablature (Plate 93). No. 4 St. Mary's Street (344) and 7 High Street (173) are two accomplished examples of shop-design of the early 19th century with shallow bowed windows (Plates 138, 139). The design of 7 High Street resembles some of the plates in Designs for Shop Fronts (1792) by I. and J. Taylor. Less elaborate designs were made in the economical Doric or Tuscan styles, as at 25–26 High Street (184), and 21 High Street (1836) (182). Fronts of even more simple design have moulded pilaster strips in place of engaged columns, as at 28–29 High Street (185). Of the later fronts, 9 Ironmonger Street (246) and 13–14 St. Mary's Street (350) of c. 1849 are noteworthy. The bow window of 31 Broad Street (141) of 1848 projects ten inches, the maximum allowed under the Stamford Improvement Act.

Offices

In the 18th century offices were frequently no more than a convenient room set aside in a private house. Such domestic counting houses are still in use today and involve no special planning; a room entered from near the front door is all that was required. The strong-room and adjoining two rooms at Torkington House, St. Peter's Street (417), approached from a side-door under the carriage-entry, were probably offices for James and John Torkington, attorneys, in the early 19th century.

The earliest building which can be identified as an office is 24 St. Mary's Street (358), built by James Bellaers, merchant, next to his house, sometime before 1779. There were two ground-floor rooms, the front one with a central entrance; the first floor was used as an extension to the house. Immediately after 1827 T. H. Jackson, an attorney, built an office at 21 St. Mary's Street (357) adjoining his house. Again there were two rooms on the ground floor, and a small strong-room behind. The wine cellar below was separately entered and sublet. The mid 19th-century office at 15 Barn Hill (102) is also of two-room plan with a strong-room below the stairs (Fig. 81).

Wharves and warehouses

The Welland, though not a river of impressive size, must have been navigable as far as Stamford during the entire medieval period, even if only by the comparatively small boats that were in use at that time. In the 13th century wool was being exported from Stamford mainly through Boston (Rot. Hund. I. 353, 357) and it was presumably the better river connection that favoured that town against King's Lynn. By the 16th century navigation was impossible, the townsmen alleging that watermills up-stream from Deeping were the main obstacles (Act of 13 Eliz. I). During the early 17th century a canal 9½ miles long was dug to bypass this stretch of the Welland (27). By the early 19th century traffic along the canal was by means of gangs of up to four lighters, each lighter of between 7 and 14 tons burden. The total load for a gang was 36 to 42 tons and the journey from Boston took up to four days (Drakard, 393).

The obstruction created by Stamford Bridge caused wharves to be confined to the banks on the downstream side. In 1756 Henry Ward made a quay on the N. bank of the Welland E. of the bridge (Court Rolls), and this is the only warehouse which remains today (450); others formerly existed on the N. side of Water Street where c. 1740 James Bellaers was landing coal and sending grain and malt down river (deeds, 16 Water Street). In 1731 Alderman Collington was importing Scandinavian timber and clay from the Isle of Wight (Mercury, 5 Aug.) and Drakard records that coal and timbers were the main items of trade in 1822 (Drakard, 393).

In 1840 the new plan for Blackfriars Estate included a wharf to the E. of Brownlow Street, but it was not built. River trade was superseded by the opening of the railway in 1846; coal was being brought from Peterborough by the following February (Mercury, 12 Feb. 1847), and the canal finally ceased to carry traffic in 1863.

Industrial buildings

Two watermills dating from the 17th century survive in the town; they are rectangular structures with water wheels at the ends (65, 66). Only the base of one windmill was recorded (67).

There are few other industrial buildings in the town, and they generally date from the early 19th century. Stamford's importance as a marketing centre for agricultural products is reflected in the early growth of a flourishing brewing and malting industry. Most of the brewery buildings have been rebuilt but maltings are still a prominent element in the town's architecture. Dating from the 19th century, they are of rubble construction with small windows and heavily-constructed floors, and most are in St. Martin's parish.

Several attempts were made to establish silk throwsting in Stamford. Of the buildings erected for this, known as 'spinning schools', only that of George Gouger remains but greatly altered (143). Part of a brass foundry of c. 1843 survives at Broad Street (138).

The number of apothecaries in the 19th century is an indication of Stamford's local status; the business at 2 Red Lion Square (278) has been in existence for 250 years. Thomas Mills was one of the more important chemists, and his apothecary's workshop survived until recently behind 19 High Street (180).

Markets

In the Middle Ages markets in Stamford were held in the open, both in the streets and in Red Lion Square. The booths in the latter became progressively more permanent until they were rebuilt as proper small shops with rooms above; these encroachments were removed in the late 18th century. The market in High Street had a covered building, rebuilt in 1751 as a roofed space with open sides (Nattes' drawing of 1804); other traders had stalls against the adjacent buildings. It was demolished in 1808 when a new shambles and market were built (61) to designs by W. D. Legg (Fig. 60). A covered corn exchange was built in 1839 to replace an open market in Broad Street (Plate 66), but this was only used until 1859 when it was replaced by a closed hall on the opposite side of Broad Street. An open Buttermarket was built in Red Lion Square in 1861 to designs by Edward Browning, and still survives.

Gardens

The larger town gardens have been altered or sub-divided, and those of c. 1840–50 on the Blackfriars site are now abandoned. The Castle site was terraced for gardens but they too have gone. William Stukeley had a large garden at 9 Barn Hill (97) with prospect mound, temples, obelisk and summer house, of which only the early 17th-century gateway, remodelled as a great alcove, remains. His collection of medieval sculptured masonry, one of several to adorn 18th-century Stamford gardens, has, like its fellows, been dispersed. (See also S. Piggott, William Stukeley, 141, 151.)

Barn Hill House (96) retains part of a formal garden, overlooked by a classical summer house (Plate 104). The surviving formal features at the garden of Vale House (250), consisting of a terrace and a bridge spanning the mill leat, are now incorporated in an informal setting (Plate 150).

Several large houses retain in their gardens terraces which lie on the line of the town wall, probably incorporating part of it. In each case the terrace faces the garden and has a parapet on the external 'wall' face. That at 38 St. Peter's Street (417) may date in its present form from c. 1840; the terrace at 3 Broad Street (128) incorporates early masonry, and its parapet was refurbished in 1721, probably by George Denshire. At 14 Barn Hill (101) and 18–19 Broad Street (136) the terrace was raised over a loggia which faced the garden. A wooden loggia was built in a similar commanding position at 8 Rutland Terrace in about 1830 (288).