Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Great Sutton Street area', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp280-293 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Great Sutton Street area', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp280-293.

"Great Sutton Street area". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp280-293.

In this section

CHAPTER X. Great Sutton Street Area

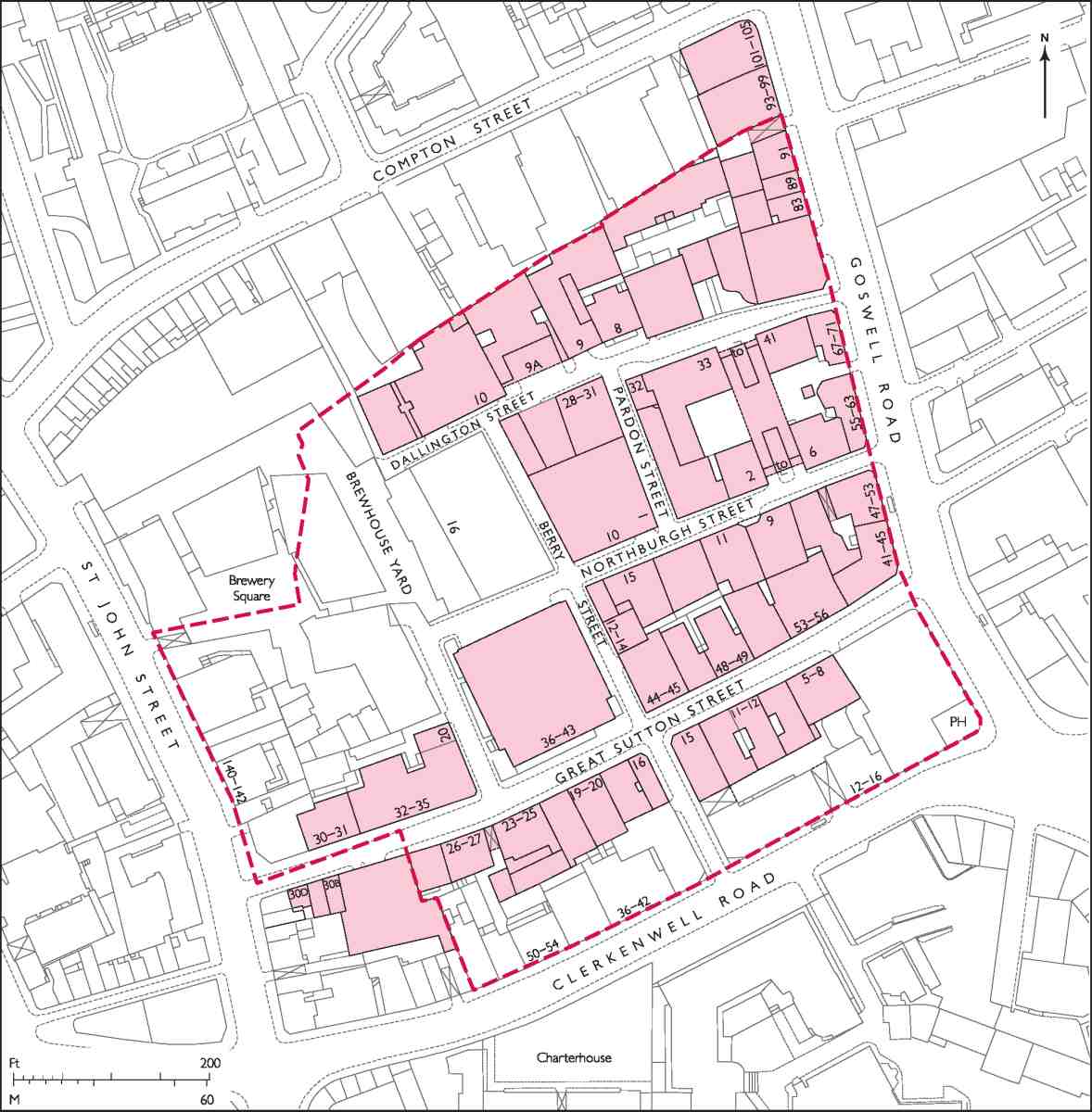

388. Great Sutton Street area. The broken red line indicates the extent of the former Charterhouse estate

The grid of streets south of Compton Street, in the angle of Goswell and Clerkenwell Roads, was mostly laid out in the second half of the seventeenth century, and its pattern has been little altered since. The streets are narrow, in some places with very narrow pavements or none at all: from this, and the tall, mostly industrial buildings the area derives its distinctive character (Ill. 388).

From 1611 until 1995 almost the whole of this district belonged to the Charterhouse (Sutton's Hospital), a small estate lying just outside the Charterhouse wall and let commercially. Most of it had formerly belonged to the Carthusian priory from which the Charterhouse evolved, remaining with it when the priory passed into lay hands after dissolution in 1538. Part had been used in the fourteenth century as a plague burial-ground, and the earliestknown building was a mortuary chapel therein, called Pardon Chapel. But it was as a predominantly industrial area that it developed in the seventeenth century, and it remained industrial until long after the Second World War. By that time the resident population, once teeming, had dwindled almost to nothing, squeezed out as new business premises replaced old houses and more recent model dwellings. With the decline of industry and commerce in the later twentieth century, this became one of the more run-down parts of Clerkenwell, but in recent years most of the hitherto shabby buildings—the majority of them unpretentious warehouses or factories ranging in date from the later Victorian period to the middle decades of the twentieth century—have been converted to loft apartments or otherwise renewed.

Clerkenwell Road, which closes the southern end of the area, did not come into being until the 1870s, and this part of it was adapted from Wilderness Row, a residential street laid out a century earlier. The present buildings in Clerkenwell Road are discussed with the rest of the road in Chapter XIV, but the development of Wilderness Row itself is dealt with here. The buildings in St John Street between Clerkenwell Road and Compton Street, together with the whole of the former Cannon Brewery site, are described in Chapter VIII.

Pardon Chapel

Founded in the wake of the Black Death by the Bishop of London, Ralph de Stratford, Pardon Chapel was built in 1348 in a field then owned by the Priory of the Order of St John, called St John's Meadow or Whitwellbeach (Ill. 389). An area around the chapel was made a burial ground for plague victims. In 1349 another plague burial ground was established to the south by Sir Walter Manny, who in 1371 founded a house of Carthusian monks on the ground between these two graveyards. (fn. 1)

The approximate site of Pardon Chapel—where masses were held to pardon the souls of those who had died before they could be given the last rites—lies to the rear of Nos 36–48 Clerkenwell Road and Nos 19–24 Great Sutton Street. The chapel itself survived well into the sixteenth century, the graveyard being used by St John's priory and, Stow relates, for the burial of suicides and executed criminals. (fn. 2)

By 1565 the chapel had been converted into a house, and had come into the ownership of Edward, Lord North, together with the surrounding fields and the former priory. The house then stood in a large walled garden, with an orchard of almost a hundred fruit and nut trees, a 'faire out house' and a dovecote. (fn. 3) During the seventeenth century it fell into decay. It was still referred to as Pardon Chapel or Church into the eighteenth century, though by then hardly any of the original fabric survived beyond some stone quoins. (fn. 4) In the early eighteenth century the Commissioners for Building Fifty New Churches considered Pardon Churchyard as a possible site for a new place of worship, and went some way towards that end, but eventually the scheme came to nothing. (fn. 5) All traces of the chapel were obliterated by redevelopment in the 1760s and 70s.

Outline of development

Early development was concentrated on the ground east of Pardon Churchyard, called Copthall after a house of that name built there after the Dissolution. In modern terms, Copthall was the area between Great Sutton Street and Clerkenwell Road, extending from a little way to the east of Berry Street up to Goswell Road. Several tenements had been built there by 1590, when a survey recorded such annoyances and encroachments as windows cut into the Charterhouse wall, laystalls, hog-yards and an open sewer running near the wall. (fn. 6) More building had taken place by 1635 when a survey of the Charterhouse estate was made by Samuel Parsons. In Copthall, Parsons found 'a handsome convenient house in good repair', with a carpenter's yard and tenement adjoining, but a number of other houses and tenements in very poor condition, including the Swan alehouse by the Charterhouse wall. Worst of all was a row of 'the most poor, rascally habitations', also built near or against the wall, whose lowlife inhabitants were in the habit of throwing excrement and other offensive rubbish into the garden, 'which in a contagious or infectious time of sickness is very dangerous both for those of the Charterhouse as also for those that desire to take the benefit of the air within the Wilderness'. (fn. 7)

389. Pardon Chapel. From the Charterhouse water-supply plan, early sixteenth century

Parsons also refers to rope-walks or 'twisting alleys' here, and a number of gardens. In the same survey, the house in Pardon Churchyard was found much out of repair, its orchard destroyed and its 'handsome complete garden' in disorder. Whitwellbeach, the much larger area north of Great Sutton Street, was then still mostly garden ground, with a few tenements and sheds. (fn. 8)

In an effort to improve this squalid patch outside its wall, the Charterhouse refused to renew the Copthall lease, which dated back to Queen Elizabeth's time, and determined to let the ground to some 'fit and able man' who would replace the old tenements. John Clarke, the Charterhouse Receiver, seemed to be such a man, and was granted leases of Whitwellbeach in 1639 and Copthall in 1641, undertaking to build three or four 'convenient' houses within seven years, agreeing also not to build within thirty feet of the wall or to make any windows looking towards the Charterhouse. (fn. 9) But he was hampered by the twenty-one year terms, the longest that the governors could grant under their Letters Patent, and was unable to find builders prepared to take building leases. Though Clarke left the Charterhouse pursued by a £2,000 claim for unpaid estate revenues, for which debt he was imprisoned, his leases of Whitwellbeach and Copthall eventually passed to his son, who seems to have overseen some development. An estate survey of 1655 records the existence of brick houses fronting Goswell Road, and weatherboarded shops on St John Street. The brick houses, called Goswell Row, consisted of two terraces built back-to-back, so that those fronting the road had no yards; the back row had small gardens. Each house comprised a cellar, with a lower room, an upper room and a garret. (fn. 10)

There were still rope-walks at this time and a number of other commercial and industrial premises, including a vinegar works, a wheelwright's and a timber yard, and a slaughterhouse. All these were on the southern part of the estate, most of Whitwellbeach remaining gardens. Some years later a 'noysome and dangerous' brew-house was built against the Charterhouse wall, its removal being ordered by the governors in 1666. (fn. 11)

Also in the late 1660s, a number of tenants, including Robert Clarke, distiller, Mary Chaire, timber merchant, Thomas Allen, gardener, and Stephen Hope, butcher, petitioned for new leases, having carried out improvements and rebuilding. By 1687, when the Charterhouse estate was thoroughly mapped by William Mar, almost the whole had been laid out in streets of small terracehouses—242 houses in all, with yards, gardens and sheds. (fn. 12)

The street pattern laid down was more or less a rectilinear grid and though clearly suggested in part by existing field boundaries (fn. 13) must have been planned with some thought and co-operation between the lessees. Great Sutton Street, following roughly the southern boundary of Whitwellbeach, was already long in existence, as was a short street running south from Great Sutton Street to the Wilderness gate of the Charterhouse. This latter street was replaced by Cross Street a little to the west in the 1770s, when Wilderness Row was created, so as to make a straight thoroughfare (the present Berry Street) from Allen Street to Wilderness Row. A northern continuation of Berry Street, a dead-end doubtless intended to link up in time with a street on the Northampton estate, survived until the mid-nineteenth century, while another piece of the grid, a continuation of Schoolhouse Yard (now the north—south arm of Northburgh Street) was later obliterated by the enlargement of Cannon Brewery in St John Street.

The two east—west streets crossing Whitwellbeach were named Little Swan Alley and Allen Street, after the gardener lessee Thomas Allen. Little Swan Alley later became Little Sutton Street. It was renamed Northburgh Street in 1937, after the Bishop of London instrumental in the founding of Sir Walter Manny's priory. At the same time Allen Street was renamed Dallington Street, after a seventeenth-century Master of the Charterhouse, and Clark or Clarke Street (probably named after the distiller Robert Clarke), became Pardon Street. Present-day Berry Street was formerly three streets: Gardens or Gardener's Street, later called Berry Street; Hooper Street, named after a seventeenth-century tenant of the Charterhouse, and Cross Street. They were united as Berry Street in 1889. (fn. 14)

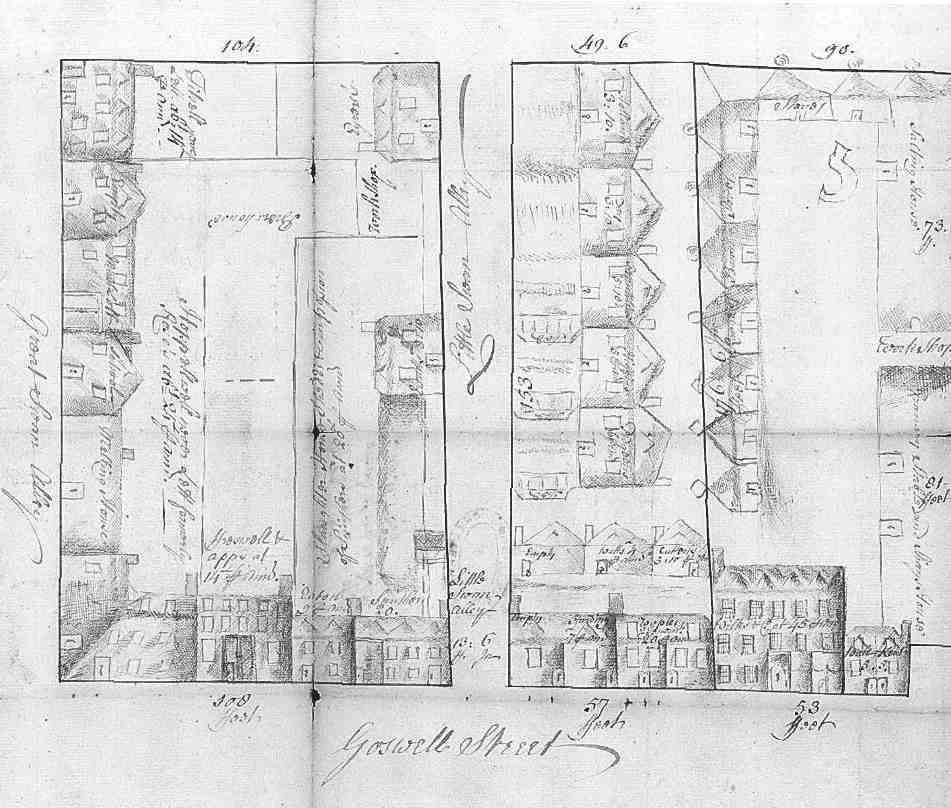

390. Charterhouse estate, 1739. Houses are shown pink, industrial buildings (or 'sheds') green

During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries the remaining gardens were built over with more workshops or courts of dwellings. Rope-walks came to take up most of the ground abutting the Charterhouse wall, including the greater part of what had been Pardon Churchyard (Ill. 390). Being close to St John Street and so in easy reach of Smithfield, the area attracted butchers, bacon-curers, slaughtermen and associated tradesmen, including, from the 1730s, the distiller Israel Wilkes the Younger, of St John's Square, who had a yard here behind Goswell Road, with slaughterhouses, a salting-house and lines of bacon-smoking stoves (Ill. 391). (fn. 15) In 1731 Philip Humphreys, the Charterhouse gardener—the kitchen garden lay west of the Wilderness—complained of the adverse effect on his crops of smoke 'from so many neighbouring Brewhouses, Distillers and Pipe-makers lately set up' in the vicinity. (fn. 16)

Periodic low-quality rebuilding on short leases continued until 1760, when the Charterhouse obtained an Act of Parliament enabling it to grant 99-year leases. In that year an agreement was made with a long-standing tenant, John Pullin, to rebuild the entire estate. (fn. 17) Pullin, a wheelwright, promised to spend £5,000 within seven years on rebuilding, but in fact lacked the necessary resources. Twelve years on, much cleared ground still lay 'bare & uncovered', and the houses that he had built were insubstantial. (fn. 18)

However, Pullin's position improved somewhat in the late 1770s. He inherited money from his brother Samuel, an Islington landowner and dairy farmer, and was able to mortgage his lease for £3,000 to a widow in Hatton Garden, Elizabeth Reynolds. (fn. 19) Progress was to remain slow, however, most of the redevelopment being carried out by Pullin and his sub-lessees up to the late 1790s, and in the event they probably rebuilt less than originally intended. (fn. 20)

Of the three hundred or more houses erected in Pullin's time, none survives, as they were steadily replaced from the mid-nineteenth century. Most were of two or three storeys, with narrow frontages between 14ft and 17ft, and had conventional two-room plans. In some inner parts of the estate there were small houses of one room to a floor, and tucked away between the Cannon Brewery and a tannery on the west side of Berry Street, in a narrow passage called Slade's Place, were some very small houses of only 12ft by 13ft. On the main roads the houses tended to be significantly bigger and better-built, particularly in Wilderness Row (see below, and Ills 396, 397). (fn. 21) Minor alterations were made to the street pattern in the way of straightening or widening. Wilderness Row, running alongside the Charterhouse wall, was the only entirely new street. (fn. 22)

Generally, the estate attracted tradesmen and some professionals to houses on the main roads, with industrial activity carried on behind, especially in and around Allen and Great Sutton Streets. (fn. 23) One of the largest of several new factories was a drug mill, built in the 1780s by John Hurwood, millstones from which are preserved outside the present building on the site, Nos 36–43 Great Sutton Street. (fn. 24)

391. Part of Goswell Street (now Road) and the eastern end of Great and Little Swan Alleys (now Great Sutton Street and Northburgh Street respectively), 1739. Right of centre is Wilkes & Co.'s bacon yard with bacon curing stoves

Already by the 1820s some houses were giving way to further industrial developments, including slaughterhouses, a dye-house, breweries, and vinegar, vitriol and gas works. Complaints were made to the Charterhouse in 1832 about the nuisance of these works and their steam engines, and to the Vestry in the 1850s about the 'boiling of putrid meat and other offal' and blood running into the drains. (fn. 25) Concerned by this malodorous neighbour, the Charterhouse refused Pullin's heirs a new lease in 1850, and when the old lease expired took the estate into direct management, with advice from the architect Philip Hardwick. New sewers were constructed, roads widened, and some of the poorest housing was pulled down. The rental value was raised tenfold. But sub-standard housing and often noxious industries continued. (fn. 26) 'Dull, badlybuilt, badly-ventilated, overcrowded' was how John Hollingshead characterized the district in 1861. (fn. 27)

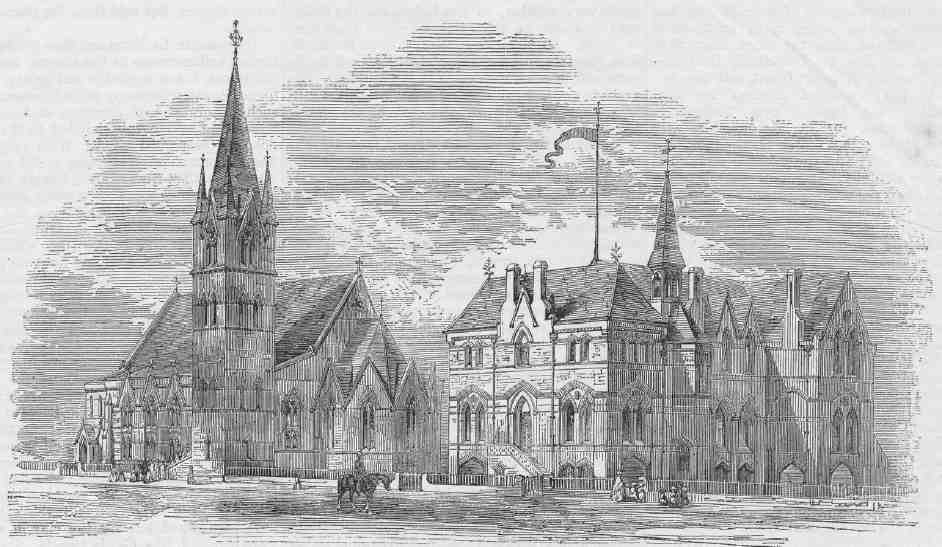

392. Designs for St Paul's Church and School, Allen Street, by T. Roger Smith, 1860. Only the school, now demolished, was built

The mid-century saw a scheme to build a church here for the new ecclesiastical district of St Paul's, Clerkenwell, of which these streets formed a large part. This followed the opening of a makeshift school and church in Compton Passage. In 1859 the vicar of Clerkenwell, the Rev. Robert Maguire, secured from the Charterhouse the offer of ground in Allen Street for permanent buildings, and designs by W. P. Griffith for a conventional Decoratedstyle church with a tower and adjoining school were published. These were not executed, however, being superseded by plans drawn up by T. Roger Smith (Ill. 392). In July 1861 the Marchioness of Northampton laid the foundation stone of the school before a 'gay and animated crowd'. (fn. 28) The completed building, which incorporated an open-arcaded basement for use as a covered playground, was judged by the Building News to have 'no very positive artistic originality, and no glaring defect'. (fn. 29)

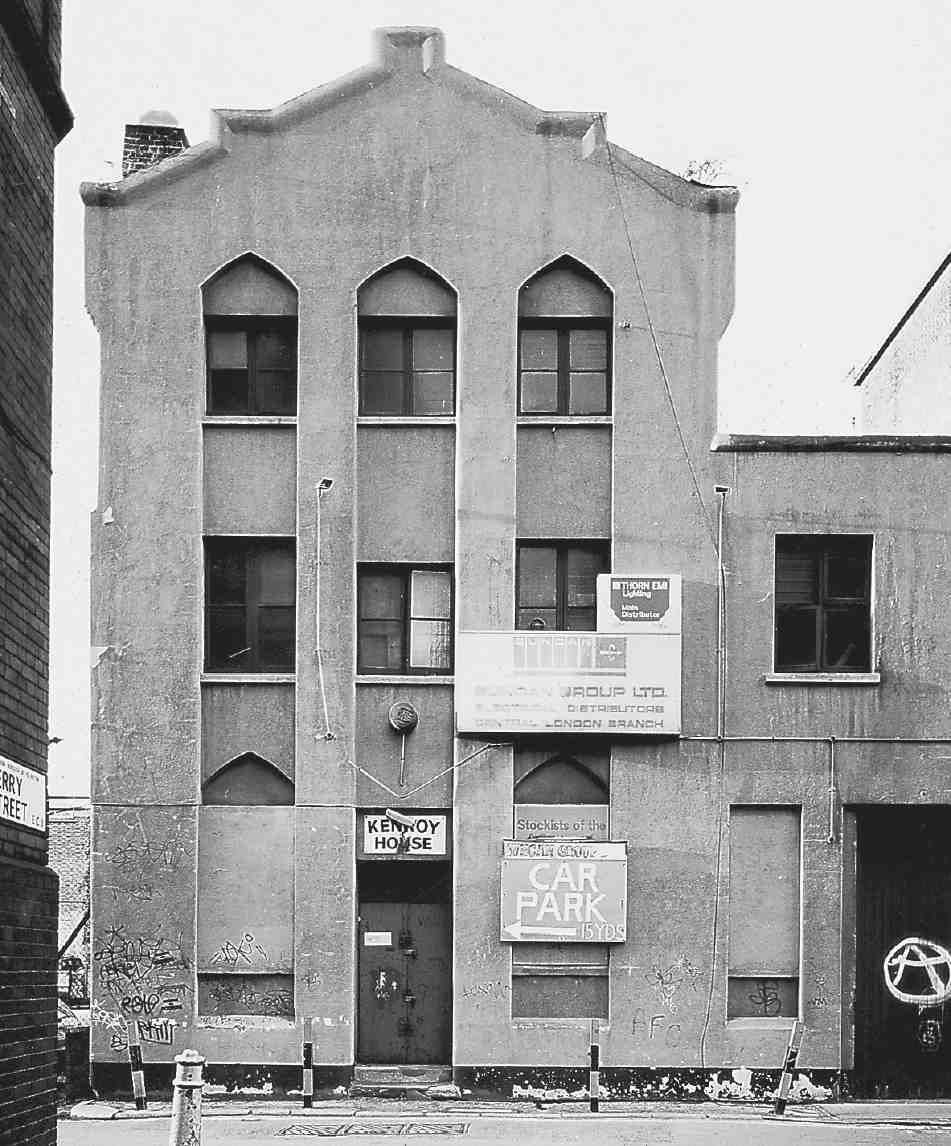

393. Kenroy House, No. 10 Dallington Street, in 1999. Speculative warehousing of 1866–7

In the end St Paul's Church was built elsewhere, in Peartree Street, on the east side of Goswell Road (in Finsbury), and to designs by Ewan Christian. By this time—1874—the school had been taken over by the School Board for London and renamed Allen Street School. It became redundant in 1881 when Compton Street School (page 324) was built almost directly behind, and by the end of the decade the site had been redeveloped with artisans' dwellings (see below). (fn. 30) Today the only relic here of the district of St Paul's is No. 8 Dallington Street (now Dallington School), a plain, stock-brick building, erected in 1905–7 as St Paul's Church Institute. (fn. 31)

394. Great Sutton Street area, mid-1870s

The site which had been intended for the church was taken for three commercial buildings, the speculation of Thomas Rowland Hill and Joseph Hill. Of these all that remains is the warehouse façade, long rendered over, and altered, of No. 10 Dallington Street, built in 1866–7, now incorporated into the front of a development of apartments (Ill. 393). (fn. 32) The first tenants of this building were a firm called Neidlinger, manufacturers of sewing machines; by 1872 it had become a printing works for James Thomas Pickburn, publisher of Clerkenwell News. (fn. 33) Its later name, Kenroy House, came from Kenroy Ltd, electrical goods merchants, here from 1970.

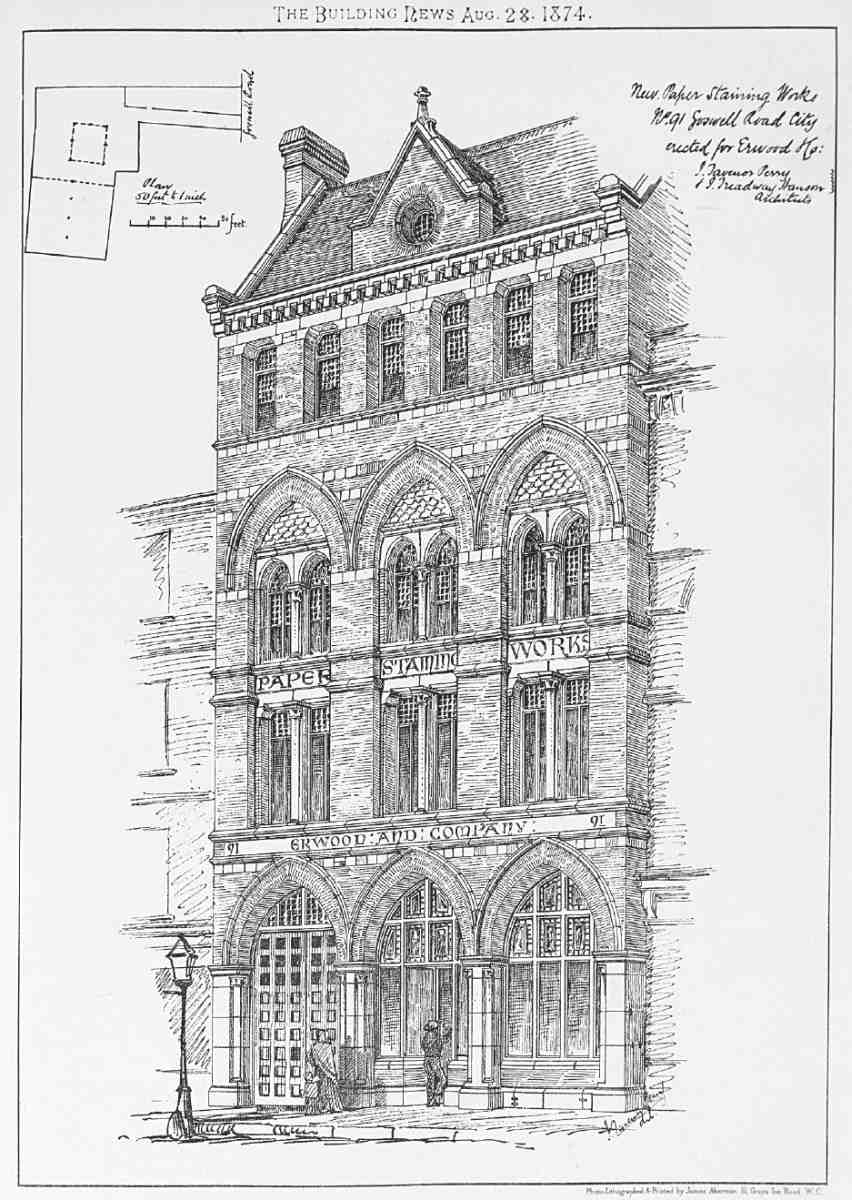

Other new buildings of the 1860s and 70s included a brass foundry of 1860 (now demolished) on the north side of Allen Street, designed for Isaac Frost by W. P. Griffith, one of several foundries in the area at this time (Ill. 394). (fn. 34) Erwood & Co.'s new paper-staining works at No. 91 Goswell Road, of 1873–4, was designed for John Edward Erwood by the architects J. Taverner Perry & J. Treadway Hanson, of the Adelphi (Ill. 395). (fn. 35) Behind a handsome Gothic façade on the narrow street frontage, of red brick and terracotta, the works comprised a large L-shaped range of workshops, warehousing and offices. The Gothic front was destroyed for the widening of Goswell Road in the early 1900s (see below); parts of the back premises may have survived, in what became Tanqueray Gordon & Co.'s wine and spirit stores. (fn. 36)

Extensive redevelopment of the Charterhouse estate followed remarks in 1884–5 by the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes as to the badness of the houses there. Although spared the particular opprobrium directed at the adjoining Northampton estate, the Charterhouse was criticized for allowing comparable problems—the incidence of house-farmers, severe overcrowding and badly constructed, poorly ventilated housing—to continue on its property. One house in Allen Street was found to be occupied by thirty-eight people, eleven of them in one small room; similar conditions were found in the cottages of Slade's Place. Many of these properties were occupied by costermongers with 'very precarious' earnings (whom the Commission felt would do better 'if they kept from drink'). (fn. 37)

395. Erwood & Co.'s paper-staining works, Goswell Road. Perry & Hanson, architects, 1873–4. Demolished

Such pressure for improvement coincided with the falling-in of a large number of 21-year leases held by one landlord for property on Great and Little Sutton Streets. In addition, the agricultural depression, which severely reduced income from its extensive country estates, focused the Charterhouse's attention on to this urban property. (fn. 38) As a result, many of the old houses and sheds were replaced by factories, warehouses and model dwellings, mostly built on 80-year building leases, granted from 1886 onwards (see below).

Wilderness Row

Wilderness Row was named after the large garden laid out with trees and walks which belonged to the Charterhouse and over which a number of the houses in the row looked (the site of the present-day St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical School). It was not strictly speaking a through road, for at the west end it tapered off into a footpath, Pardon Passage, the medieval alley which had given access to Pardon Churchyard.

A proposal to build a new street from St John Street to Goswell Road 'near the hospital wilderness' was made to the Charterhouse by 'some workmen' in 1726. The governors reacted favourably, but the scheme was nonetheless soon dropped. (fn. 39) But with the redevelopment of the estate by John Pullin from 1760 the idea returned. The name Wilderness Row first appears in ratebooks for 1775, along with nine new houses there. Two more had been built by 1778; another nine were added in 1780–5, and more were still being built in the late 1790s. (fn. 40) Several builders were involved, taking leases from Pullin. Some of the bigger takers were: Thomas Lupton, bricklayer of St Martin in the Fields; John Casbolt of Cloth Fair; Andrew Nicholl, stonemason of Aldersgate Street; and George Head, a Clerkenwell bricklayer. (fn. 41)

396. Nos 12–30 Clerkenwell Road, c. 1905, formerly part of Wilderness Row. William Thackeray lodged at the house second from left (No. 28) in 1822–4

The houses of Wilderness Row were the best on the estate, having relatively broad frontages, and generally comprising three floors with mansard attics (Ill. 396). Ostensibly they had an attractive outlook over the Charterhouse, but lessees complained of the 'decayed state' of the Charterhouse wall, which 'affords a very bad object … & greatly impedes the letting [of the houses] & the further covering of the said ground'. (fn. 42) A number of clergymen resided here, including the vicar of St James's, Clerkenwell, the Rev. Henry Foster. In 1804–5 the antiquary and topographer John Britton lived at No. 21 (on the site of the present No. 48 Clerkenwell Road), and with him his pupil, the watercolourist Samuel Prout. Two of the clown Grimaldi's family lived at No. 25, Samuel c. 1800–4, and James in 1805; their successor at the house was the engraver Joseph Beckwith, an early member of the London Corresponding Society, here from about 1807 to 1830. William Elliott, a scientific-instrument maker, occupied No. 26 from 1808 to 1816. (fn. 43) During the 1820s two houses were used by Charterhouse School to accommodate boys, among them Thackeray in 1822–4, in what was later No. 28 Clerkenwell Road. (fn. 44)

In 1785 Welsh Calvinistic Methodists opened, or more likely re-opened, a chapel in a yard at the west end of Wilderness Row—the site is at the rear of the present Nos 64–68 Clerkenwell Road. This was probably the place where John Wesley had preached in 1769, noting in his journal that it had been built 'on the very spot of ground whereon … Pardon Church stood'. (fn. 45) Enlarged in 1806, this Wilderness Row Chapel was acquired in 1823 by Wesleyan Methodists, who also had a vestry and schoolroom adjoining. They moved to St John's Square in 1849, after which the building was re-opened by Baptists as Zion Chapel. It closed in 1878 but was still in existence in 1920 when it was in use as a builder's store and workshop. Its remains were later incorporated into a garage, since demolished. (fn. 46)

When Wilderness Row became part of Clerkenwell Road in 1879 the houses were unaffected. Many had by then been adapted and extended into workshops and showrooms for the jewellery and watch-making trades, which had begun to be concentrated here from about 1840. (fn. 47) By about 1890 this was one of the main centres for the clock and watch industry in Clerkenwell, and was to be one of the few streets where makers and dealers remained in force once cheap imports had brought decline in the early 1900s. Several branches of the trade were represented here as late as the 1980s. (fn. 48)

Goswell Road Improvement

The west side of Goswell Road north of Great Sutton Street as far as Upper Ashby Street was set back by the London County Council in 1904–5. Local residents and their representatives in the vestries had long been clamouring for such widening, as the roadway here was frequently congested. Not only was this a major route for buses and general commercial traffic, but there were two businesses here with large fleets of vehicles: the hauliers Carter Paterson, and the distillers Tanqueray Gordon. Both had extensive premises on each side of the road (though their main buildings were on the east side, which was unaffected by the scheme). (fn. 49)

Clerkenwell Vestry pressed the LCC to take on the widening as a 'metropolitan' street improvement, whereby the Council incurred all the costs, but the LCC refused to act until 1899 when both Clerkenwell and St Luke's Vestries agreed to contribute £20,000 between them— something under a tenth of the estimated cost. (fn. 50) Under the terms of the LCC (Improvements) Act of 1900 authorising the work, the Charterhouse and the Marquess of Northampton bought back the surplus land, and so, unusually, it was not the metropolitan authority that oversaw the redevelopment of the street frontage after the widening, but the original landowners. (fn. 51) An exception to this was was the house and surgery of Dr Evan Jones, which the LCC was obliged to rebuild in 1904–5, following legal action. The new building, two doors away, took the old number (Ills 397, 398). Its design, by the LCC Architect's Department, had to be approved by E. B. I'Anson, surveyor to the Charterhouse, to which the freehold reverted on completion of the building. (fn. 52)

397. Nos 73–89 Goswell Road in 1903, shortly before demolition for road-widening. Dr Evan Jones's surgery (No. 89) at far right

398. Goswell Road in 1951, showing buildings erected after road-widening in 1904–5. Left to right: Nos 81, 83, 89, 91 and part of 93–99. Nos 81 and 91 demolished

The surgery apart, the buildings erected here on the Northampton and Charterhouse estates shortly after the road-widening were mostly warehouses or factories of the same utilitarian character as in the streets behind. At the northern end, on Northampton land, Nos 93–99, since rendered and converted to offices and flats, were built in 1907–8 as showrooms, stabling and stores for George Redhouse & Son, carriage builders. The adjoining block at Nos 101–105, at the corner with Compton Street, was added for Redhouse as warehousing in 1909–10. (fn. 53) Redhouse's architect was William Leonard Dowton, of City Bank Chambers, Bedford Row. (fn. 54)

On the Charterhouse estate, Nos 55–63 and 67–71 were designed by Edward Haslehurst for the builder Frank Linzell of East Finchley, and erected as a speculation in 1907–8. (fn. 55) A row of segmental pediments along the roofline adds rhythm to the otherwise commonplace red-brick and concrete elevations. The only other survivor from the period is No. 83 (adjoining No. 89: there is no 85 or 87), built in 1907 by W. Irwin of Essex Road for the City Sites Development Co. as warehousing and public diningrooms (Ill. 398). (fn. 56)

The frontage between Great Sutton Street and Northburgh Street remained empty for many years, largely because of the glut of new warehousing already erected on the widened road. (fn. 57) After a number of failed attempts to find a taker, the Charterhouse finally agreed a lease with A. Class & Son, who in 1927–8, with Herbert Wright as architect, erected a factory for Charles Straus, a leather-bag manufacturer: Straus House, now Nos 47–53. (fn. 58) This was to be the first of many such buildings developed on the Charterhouse estate in the ensuing years by this builder and architect (see below).

Industrial dwellings of the 1880s and 90s

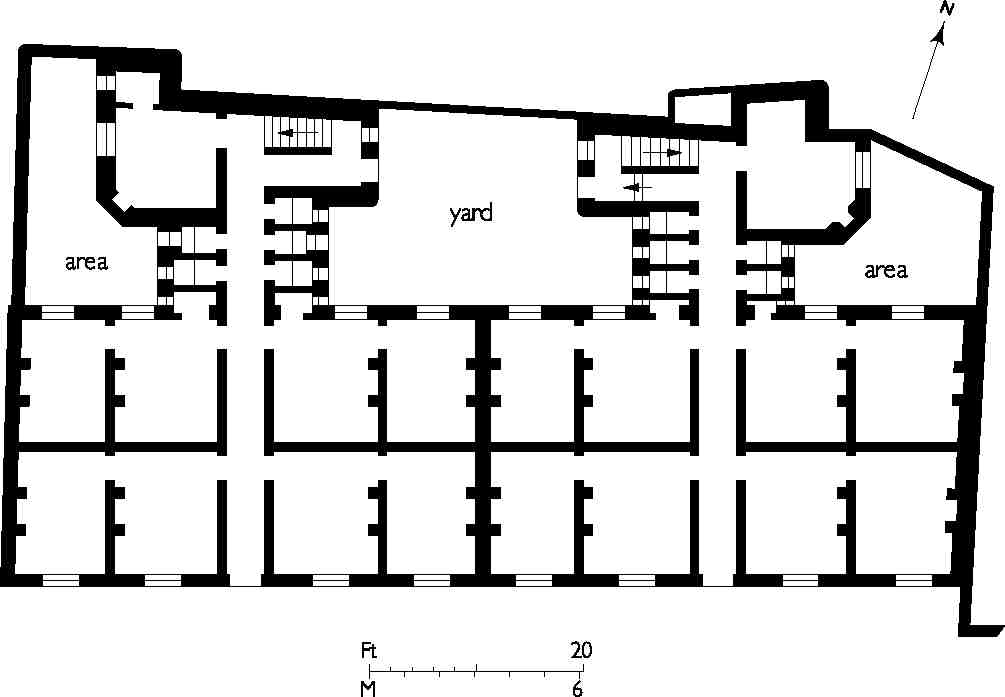

Four separate groups of model or 'industrial' dwellings were erected on the Charterhouse estate in the late nineteenth century, all but one of them after 1886, once the governors had absorbed the findings of the Royal Commission on working-class housing. None survives. All were privately built and run, and though occupied generally by 'respectable' tenants seem to have lacked the greater privacy and better facilities that by then were becoming usual in blocks built by the philanthropic dwellings companies.

The first was Charterhouse (later Charter) Buildings, a small block on the west side of Hooper Street (now part of Berry Street), erected in 1880–1, in advance of the Royal Commission. The developer was William Philip Turner, a Peckham builder, for whom a lease had been negotiated by John Clark Williams, owner of the adjoining drug mills. Having constructed the dwellings himself, Turner almost immediately sold his interest on to John Grover, the Islington builder, who retained and presumably ran the block, which comprised 16 three-roomed apartments, each of the four floors having a shared washhouse and WCs. (fn. 59) At the time of Charles Booth's social survey the general decency of the residents was suggested by flowers and the absence of broken windows. (fn. 60)

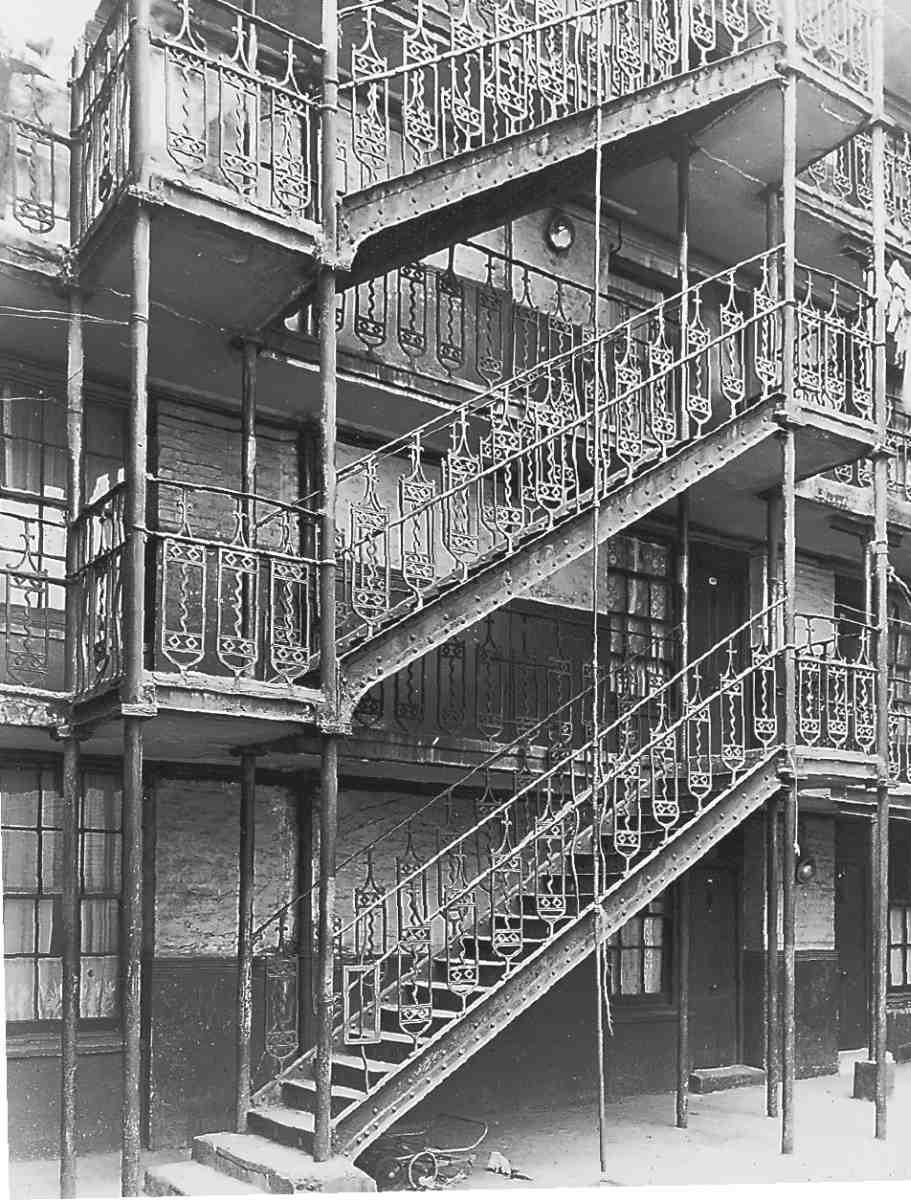

In 1889 the short-lived Allen Street School, which had been re-purchased by the Charterhouse from the London School Board, was taken by William James Feary, a Goswell Road builder, as a site for artisans' dwellings. (fn. 61) Known at first as St Paul's Buildings and later as Cavendish Buildings, these opened in 1890, with 72 twoand three-roomed flats arranged in four linked six-storey blocks, those at the north and south ends apparently retaining some of the school fabric. (fn. 62) Access was via a doorway on Dallington Street into a small courtyard, where a large, cast-iron staircase with decorative balustrading led to long, gallery-like balconies of similar design (Ill. 399).

399. Cavendish Buildings, Dallington Street. External staircase, 1956. Demolished

At about the same time two other smallish five-storey blocks of dwellings were built on the north side of Little Sutton Street near Goswell Road. They were called Little Sutton Dwellings, and later became Nos 2–4 Northburgh Street. Work began in 1887 under a Mr Wood (with whom the Charterhouse had agreed a lease), but soon drew to a standstill. E. Cousins & Co., the local builders who took over the job, also failed to complete it. (fn. 63) The dwellings were finished in 1892 by a Wandsworth Road builder, E. J. Thorp, for a new owner, Frederick George Coward, an architect of Great James Street, Bloomsbury. (fn. 64) Despite Coward's involvement, the buildings seem to have been completed to designs by Wood's original architect, a 'Mr Evans'—possibly W. C. Evans (later Evans-Vaughan), who had some local connection and later designed Finsbury Town Hall. (fn. 65) Little Sutton Buildings provided 48 mostly two-room tenements, with common lavatories on each floor, and a wash-house on each flat roof (Ill. 400). From the outset the Charterhouse had worried that Evans's plans seemed to be for dwellings of 'a very moderate character'; Booth's investigator thought them 'rather rough' and the residents poor, but found no thieves or prostitutes. (fn. 66)

400. Little Sutton Buildings, Little Sutton (now Dallington) Street, typical floor-plan showing two-room tenements. W. C. Evans, architect, 1887–92. Demolished

A much larger development was Sutton Buildings, of 1888–9, which replaced some houses between what are now Berry, Northburgh and Dallington Streets. This was another venture by W. J. Feary, who built them on a long lease from the Charterhouse, obtaining a mortgage from the Monarch Building Society of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Grouped around a courtyard, they contained more than a hundred flats. As part of the scheme, Feary also adapted the adjoining houses at Nos 5–9 Little Sutton Street. (fn. 67) Sutton Buildings were pulled down in 1894 to make way for a new fermenting house at the Cannon Brewery (now No. 16 Brewhouse Yard, page 234). (fn. 68)

Little Sutton Buildings were roundly condemned in a 1920s report on the Clerkenwell property of the Charterhouse and St Bartholomew's Hospital, for their 'general neglect, filth and dirt', the tenants all appearing 'apathetic and dulled with the depression of their surroundings'. (fn. 69) They survived until after the Second World War. Cavendish Buildings were demolished in 1959, Charter Buildings about 1968. (fn. 70)

Commercial redevelopment from the 1880s

In the closing decades of the nineteenth century many of the remaining small house-plots disappeared with the building of more factories and warehouses. Nearly all of these were speculative ventures, built on 80-year leases granted by the Charterhouse from 1886 onwards. All were substantially built with plain exteriors, mainly of pale Suffolk, York or gault brick, or grey stocks, sparingly ornamented with salt-glazed brick or stone dressings; their four or five floors of showrooms or workshops well lit by large plate-glass windows. Inside, timber floors were supported on strutted timber joists, iron or steel beams and cast-iron columns. (fn. 71)

Among the developers the most prolific was Mark Bromet, rag and general merchant and tenant of the Charterhouse, often in partnership with his brother, Albert. A large quantity of their characteristic pale-brick faced warehousing survives, in and around Northburgh, Berry and Great Sutton Streets (Ill. 401).

A few slightly more architecturally adventurous buildings were individually commissioned by their occupiers, such as Nos 8 and 10 Northburgh Street (1892 and 1893–4), built for manufacturers respectively of folding boxes and paper bags (Ill. 402).

In the new buildings the range of activities was in some contrast to the noxious trades previously in evidence. Among early occupants were clothing manufacturers: milliners, mantle-makers and collar-makers, leather manufacturers, glove-makers and furriers. The printing trade was also well represented, along with book-binding, engraving and stationery manufacture. Continuing a long-standing tradition were several butchers and tripedressers. Many of these trades remained until the late twentieth century. (fn. 72)

In the early twentieth century the widening of Goswell Road (see above) led to yet more new building of a similar sort, and the 1930s saw extensive redevelopment with warehouses, particularly along Great Sutton Street, by the builder-developers A. Class & Son. This firm had started in the 1920s at No. 80 Chapel Street (now Market) in Pentonville, dealing in glass and china, but moved into building and developing, with a yard at Nos 28–29 Great Sutton Street. (fn. 73)

Class & Son's involvement in this area began at a time when the Charterhouse was looking to dispose of the remaining old houses to developers. (fn. 74) Their early work on the estate included Nos 50–54 Clerkenwell Road (1932–4), Nos 21–29 Great Sutton Street (1933–6) and Nos 140–142 St John Street (1937). Thereafter the Charterhouse came to rely on the firm, which dominated the rebuilding of the estate well into the 1950s. They worked generally in collaboration with the Pentonville architect Herbert A. Wright (later the firm of Wright & Tidmarsh), and also worked in other parts of Clerkenwell including Chapel Market and Rosebery Avenue. Stylistically, their buildings were severely plain but instantly recognizable, with broad red brick façades, long rows of squarish windows, and continuous concrete or stone lintels, the relentless horizontality only occasionally interrupted by giant brick pilasters (Ill. 403).

During the Second World War about a dozen properties were damaged beyond repair and subsequently demolished. Several factories and warehouses were built on these bomb-sites in the late 1950s and early 60s, and commercial development continued into the mid-1970s, when a large speculative warehouse was built at Nos 36–43 Great Sutton Street.

Unlike other parts of Clerkenwell, the Great Sutton Street area was still distinctly run-down when in 1995 the Charterhouse sold its property here, for £7.5 million, to Bee Bee Developments, the company established by the Irish entrepreneurs Alfred Buller and Craig Best. At the time the annual gross rental income was over £900,000, of which £565,000 came from leases due to expire in the following three years. But within those three years property values here rose by some 50 per cent, partly driven by the developers' first warehouse conversions, and the area has since become a thriving residential and business quarter, characterized by creative and media companies, art galleries and designer-furniture showrooms. (fn. 75)

401. Warehouse developments of the 1890s by Mark and Albert Bromet and others at the corner of Berry Street (Nos 12–14, left) and Great Sutton Street (Nos 44–49)

402. No. 10 Northburgh Street in 2007; William Cubitt & Co., builders, 1893–4

403. Great Sutton Street, looking east towards the junction with Berry Street. Warehousing of the 1930s, mostly by Wright & Tidmarsh, architects, for A. Class & Sons; Nos 32–35 to left, Nos 21–29 to right

Individual buildings

Berry Street

No. 4, and No. 15 Great Sutton Street (Berry House). This was built in 1937 for the existing tenants at No. 4 Berry Street, Lees & Sanders Ltd, precious metal refiners, bullion dealers, and sweep smelters. The architect was Frederick J. Gibbins of Goswell Road (Ill. 404). (fn. 76) The building is steelframed, and faced in bands of Fletton and gault brick, with concrete lintels. It originally comprised a basement refinery, with offices, workshops, showrooms and stores above. (fn. 77)

In 1996–7 the building was converted to offices and apartments by the architects Campbell & Campbell, who lengthened most of the window openings, and added the upper-floor metal balconies and roof extension. (fn. 78) A large metal clock on the Berry Street front is a relic of Lawson, Ward & Gammage, wholesale jewellers, who were here for some years from the 1950s. (fn. 79)

Nos 12–14. Warehouses, faced in gault bricks, completed 1892 (Ill. 401). William Scrivenor, builder, of Regent's Park, for Mark and Albert Bromet. (fn. 80)

Dallington Street

Nos 1 and 2. No. 1 offices; curved, blue-painted front with glass-block panels (Ill. 405). No. 2 (Enclave Court) flats, faced in stock brick. 1997–2001, James Lambert Architects for Dallington Lofts Ltd. (fn. 81)

404. Berry House, No. 4 Berry Street and No. 15 Great Sutton Street in 2007; Frederick J. Gibbins, architect, 1937

405. Nos 1–2 Dallington Street in 2007

No. 9. Red-brick warehouses of 1909, built for Reginald Filmer, folding-box manufacturer. (fn. 82)

No. 9A. Small factory-warehouse of 1960, designed for Lumos & Co., tableware manufacturers, by Johnston Evans & Co., surveyors; recently remodelled as flats (Ill. 406). (fn. 83)

406. No. 9a Dallington Street in 2007

No. 10. Apartment building of 2003–5 by GML Architects for the developers CYZ Ltd, incorporating the retained façade of a warehouse of 1866–7, Kenroy House. (fn. 84)

Nos 28–31. This was built in the early 1900s as stables and stores on either side of a yard. For many years the stables to the west, originally single-storey, were used by the Cannon Brewery Co., and the two-storey stores by a firm of drug and chemical manufacturers. The whole block was substantially rebuilt about 1958 under the surveyors Chamberlain & Willows, for E. Mason & Sons, drawingoffice equipment suppliers. In 1996–8 it was enlarged and converted into maisonettes and mews flats as 'Dallington Square', to designs by Campbell & Campbell, architects. (fn. 85)

Nos 33–41 (and 2–6 Northburgh Street). Extensive warehouse speculation of 1961–2 on site of bombed buildings, by Hackney Estates. Architects: Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn. H-shaped blocks with central staircases to both street fronts, faced mostly in dark-grey and lightbrown brick. (fn. 86)

Great Sutton Street

Nos 5–8. Workshops and warehousing of 1962, built for East City Investments Ltd; part of same development as Nos 12–16 Clerkenwell Road (1959), behind. Both designed by Richard Seifert & Partners: brick and glass facing, on a reinforced-concrete frame. (fn. 87)

407. Nos 17–18 and 19–20 Great Sutton Street in 1935, in occupation of Robert Pringle & Sons

Nos 9–10, 13–14. Speculative warehousing of the 1950s, replacing bombed buildings (along with Nos 18–30 Clerkenwell Road) by A. Class & Son; Wright & Tidmarsh, architects. (fn. 88)

Nos 11–12. Rebuilding of bombed premises, c. 1951, for J. L. Bruce Ltd, manufacturing opticians, the existing lessees. (fn. 89)

No. 16, Sutton Arms. Rebuilding of 1897, with red-brick upper floors and stucco surrounds to segmental-headed windows. (fn. 90)

Nos 17–18. Speculative warehouse built by Perry Brothers for Mark Bromet, 1897–8. (fn. 91)

Nos 19–20. Part of the watchmakers Robert Pringle & Sons' Wilderness Works (see Nos 36–42 Clerkenwell Road, page 400 and Ill. 576). No. 20 was built for Pringles in 1897–8 and No. 19 was rebuilt as an extension to it in 1907–8. During the First World War Pringles expanded further, taking over Nos 17–18 adjoining (Ill. 407). (fn. 92)

Nos 21–29 (Ill. 403). Nos 23–29 were built as a speculation by A. Class & Son in 1938, to designs by Herbert Wright, architect. Nos 21–22 were added c. 1953, in matching style, following bomb damage to the existing building on the site. (fn. 93)

408. Nos 30b–d Great Sutton Street, houses and shops of 1887–9, in 2007

Nos 29½ and 30A. These two sites, largely cleared c. 1994, are undergoing redevelopment with offices and flats at the time of writing (2007). The new building incorporates the retained façade of No. 30a, built as a dairy in 1886 to the design of George Waymouth, architect. No. 29½ was formerly a car park. The architects for the new scheme, for Bee Bee Developments, are Hawkins/Brown and the work is being carried out by a design-and-build company, Gilmac Building Services. (fn. 94)

Nos 30B–D. This row of red-brick houses and shops was built in 1887–9 for Richard Bowman, probably a Goswell Road jeweller of that name (Ill. 408). (fn. 95)

Nos 30–35 (and No. 20 Northburgh Street). Factory, built as a speculation by A. Class & Son, 1935; Herbert Wright, architect (Ill. 403). (fn. 96)

Nos 36–43. Large, square and oddly official-looking, this is one of the handful of commercial buildings in Clerkenwell dating from the economically troubled decade of the 1970s; it is also among the more architecturally refined of post-war commercial buildings locally (Ill. 409). Originally to have been a warehouse and showrooms, it was designed in 1973–4 by the architect Ronald Trebilcock for Withdean Securities, a development company belonging to Nathan and Philip Class, of the family of builderdevelopers closely associated with the Charterhouse estate from the late 1920s.

The development seems to have been sold well before completion to two insurance companies. A lease was agreed in 1977 with the news agency Reuters, which wanted the building for its London Technical Centre. A number of alterations were made, with Trebilcock as architect, including the insertion of a mezzanine between the ground and first floors, the building being completed in 1978. The main contractors were Marples Ridgway Building Ltd. (fn. 97)

The facing of grey-brown brick, uninterrupted by ornamentation or dressings, makes a seamless transition from areas of curtain-walling to the cladding of elements of the reinforced-concrete frame, which are thrown into prominence by the recessing of the windows. The top two floors are contained in a glazed mansard, the framework here of steel, clad in aluminium.

Displayed in front of the building, on the corner with Northburgh Street, are six mill-stones, discovered during excavation for the new building. These belonged to the drug mills erected here around 1786 by John Hurwood. (fn. 98)

Nos 44–47. Warehouses, faced in gault bricks, completed 1892 (Ill. 401). William Scrivenor, builder, for Mark and Albert Bromet. (fn. 99)

Nos 48–49. Warehouse of 1893–4, faced in gault brick (Ill. 401). Built for John Oliver, jewellery-case maker, who was among the early occupants. The builder was A. J. Jones of Ealing. (fn. 100)

409. Nos 36–43 Great Sutton Street, in 1999; Richard Trebilcock, architect, 1974–7

Nos 50–56 (and Nos 9–11 Northburgh Street). Extensive speculative development of 1960–2, designed by G. H. Inman, H. A. G. Darlow and M. Platt of Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn. (fn. 101) Concrete frame, with green aggregate panels.

Northburgh Street

No. 8. Superior warehouse building with Classically treated façade in pale brick with minimal moulded ornamentation. Built 1892 by Thomas Crossley of Bromley for Reginald Filmer, folding-box manufacturer, whose firm remained here until the Second World War. The building was refurbished for commercial use in the early 1990s, but having remained empty was converted to flats (for Sky Properties) five years later. (fn. 102)

No. 10 (with Nos 8 Berry Street and 1 Pardon Street). Factory, built 1893–4 by William Cubitt & Co. for Edward Saunders, paper-bag manufacturer (Ill. 402). Brick-built, with iron girders and columns. Faced externally in red brick, with sparing decoration in the form of ground-floor rustication and rubbed-brick voussoirs to the windows. Pedimented entrance on Northburgh Street.

Saunders' firm remained here until 1937, when it moved to Park Royal. The building has since been occupied by the Post Office (for stores), button manufacturers and printers. (fn. 103)

Nos 13–17. Built as warehousing or factory space in 1899–1900 by Perry Brothers for the developers Mark and Albert Bromet. Faced in gault brick. No. 15 was from the first intended as a new printing works for Gilbert & Rivington of St John's Square. (fn. 104)