Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Farringdon Road', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp358-384 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Farringdon Road', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp358-384.

"Farringdon Road". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp358-384.

In this section

- CHAPTER XIII. Farringdon Road

- Origins and Planning

- Construction, 1841–56

- Co-construction with the Metropolitan Railway, 1860–8

- The pattern of building development, 1864–92

- Social impact and social housing

- Commercial architecture in Farringdon Road, 1860s–90s

- House and shop building, 1870s

- Commercial character and change since the late Nineteenth Century

- North of Baker's Row

CHAPTER XIII. Farringdon Road

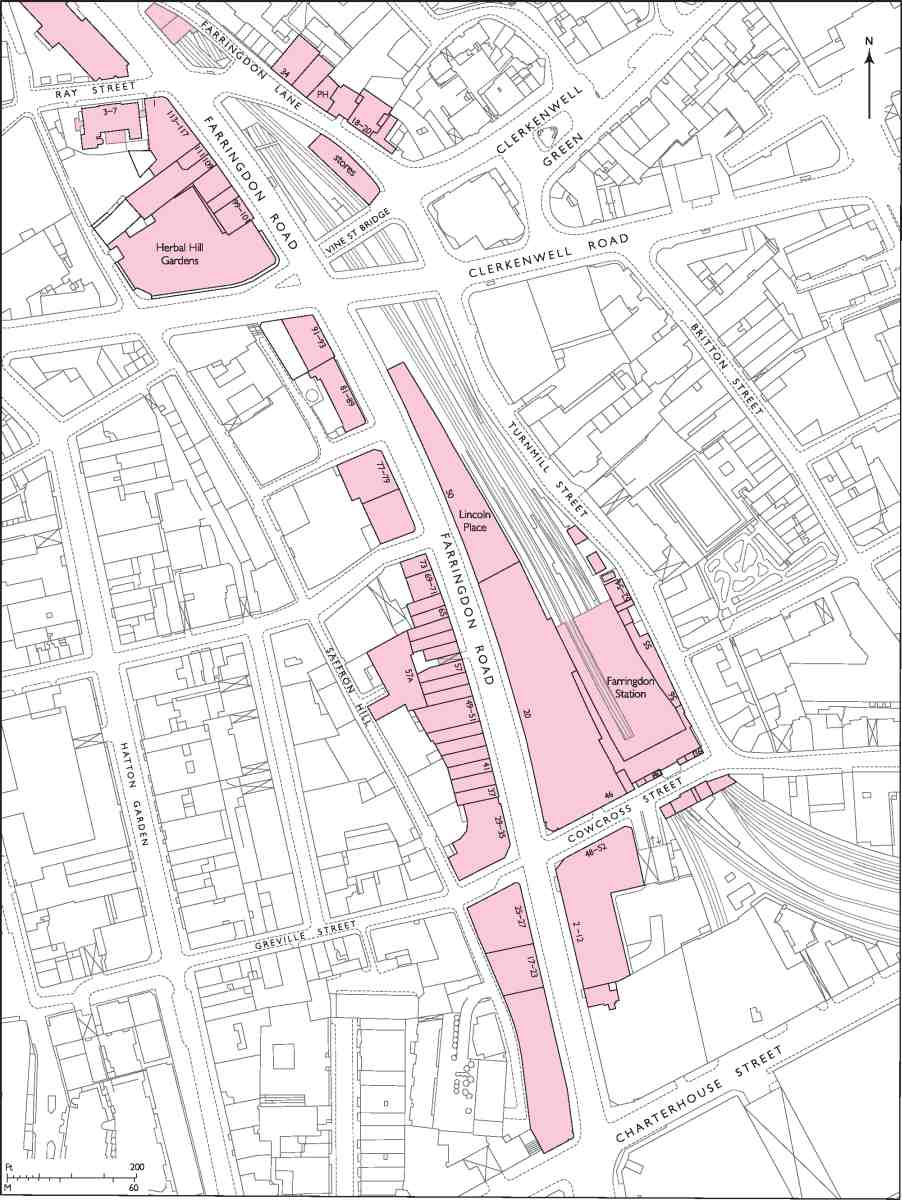

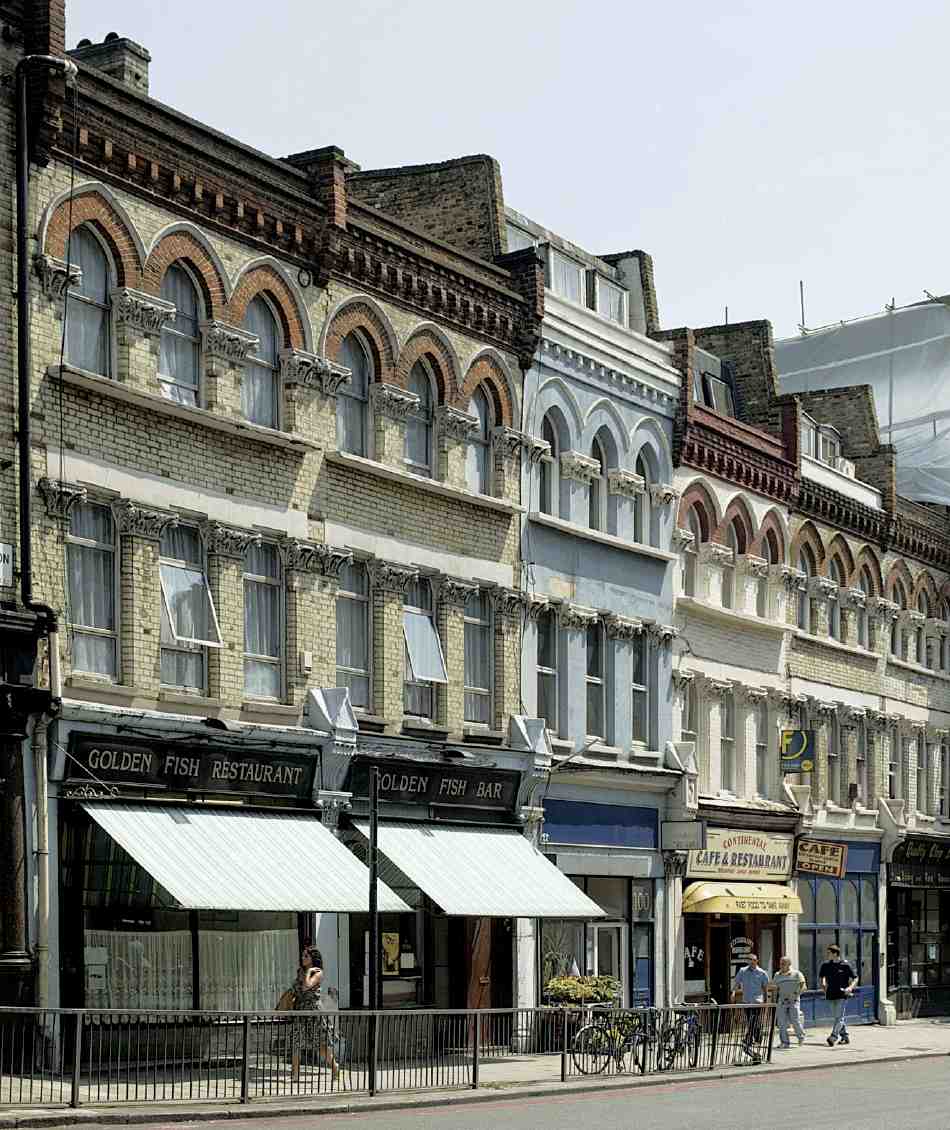

503. Farringdon Road, from Charterhouse Street to Ray Street

Farringdon Road, which forms the greater part of the highway between Blackfriars Bridge and King's Cross, is the earliest of three major roads cut through Clerkenwell in the Victorian period. Like Clerkenwell Road and Rosebery Avenue, it had an enormous impact on the terrain, not just as a new route and topographical boundary across a tortuously laid out district, but also in bringing about wholesale redevelopment of the building fabric. With the making of the road some of the worst social and sanitary blots were erased from the local map, and opportunities provided for the erection of commercial premises on a large scale, transforming the economic and architectural character of the western fringe of Clerkenwell.

This transformation was neither smooth nor speedy. There were several contributory factors, the most important being the lack of a single executive body to carry out the project, widely recognized as a thoroughly desirable one. The creation of the southern half of the road, from Farringdon Street in the City to Clerkenwell Green, took from 1841 to 1856, and this after years of proposals and preparations. The other half, not strictly a new road but a reconstruction of most of Coppice Row and part of Bagnigge Wells Road, was built in the 1860s in conjunction with the cut-and-cover work for the Metropolitan Railway. The underground railway, and additional mainline tracks from King's Cross, continued southwards in a cutting alongside Farringdon Road, necessitating a series of bridges for the side streets and one crossing of the railway lines.

For years, Farringdon Road was characterized by the wasteland of cleared sites and shored-up houses through which it passed. Building development, mostly for manufacturing and warehousing, but with some block dwellings, terrace-houses and pubs, did not begin until the mid-1860s and continued into the late 1880s. Essentially utilitarian, the big new mercantile buildings were, if seldom individually adventurous in style, imposing en masse. Despite considerable reconstruction since the Second World War, Farringdon Road retains much of this firstgeneration commercial development.

The following account covers the development generally of the whole length of Farringdon Road, part of which lies outside Clerkenwell, in the parishes of St Sepulchre Without and St Andrew, Holborn, and the Liberty of Saffron Hill. It also includes Farringdon Lane, the northern continuation of Turnmill Street up to Pear Tree Court, which was numbered as part of the eastern side of Farringdon Road from 1883 until 1979 (Ills 503, 504). Clerkenwell Workhouse, which stood on the site of the present-day Nos 143–157, and the eighteenth-century development north of the workhouse site as far as Rosebery Avenue, are described in volume xlvii of the Survey of London. The Peabody Estate in Pear Tree Court, which has a long frontage to Farringdon Lane, is described in Chapter I.

Origins and Planning

In some respects an archetypal Victorian improvement, Farringdon Road was nevertheless the final stage in a piece of town planning begun in the mid-eighteenth century, while in general terms it had been conceived of even earlier. A road through the Fleet valley linking the City with western Clerkenwell was part of Wren's thinking for his projected reconstruction of London after the Great Fire. But it was not until the building of the first Blackfriars Bridge in 1769 that the idea started to become a practical proposition. Such a road was suggested by John Gwynn, in his London and Westminster Improved, while the bridge was still under construction. The creation by the City Corporation in 1769–71 of Blackfriars Road, and the road intersection at St George's Circus, provided a magnificent approach to Blackfriars Bridge from the south, quite unmatched on the other side of the river. Carried on to Clerkenwell or beyond, a northern counterpart offered the prospect of 'a noble, free and useful communication' between Surrey and Middlesex, and of 'amazingly improved' property along the way. (fn. 1)

From the start, the formation of the northern road was bound up with the necessary task of covering in the Fleet, long since degraded from a river into a common sewer. Below Holborn, the Fleet had been canalized by the City, under the direction of Wren and Hooke, and, following the commercial failure of the canal, the stretch between Holborn and Fleet Street had been arched over in the 1730s for the construction of Fleet Market. (fn. 2) With the creation of New Bridge Street to link Fleet Market and the new Blackfriars Bridge, the process was taken further. North of the City, the Fleet remained in large part open.

Gwynn's was evidently not the only voice promoting a northern extension, which despite an absence of definite proposals was widely felt to be in the offing. Property owners along the presumed way even took the precaution of granting short leases or leases terminating should the road materialize. The scheme continued to surface from time to time, but not until about 1820 were any firm steps taken by the City authorities. (fn. 3) In 1826–32 Fleet Market was cleared, the site redeveloped as Farringdon Street (the name commemorating a City goldsmith of medieval times), and the old buildings were replaced by a new 'Farringdon Market' for fruit and vegetables on ground adjoining.

Farringdon Street completed, the Corporation turned its attention to the next phase of the northern road, to Clerkenwell Green. Three possible routes had already been mapped out for the City by the architect James Elmes in 1830: two roughly following the Fleet valley, a third veering eastwards to cut through the south end of Red Lion (now Britton) Street and on to the south-east side of the Green. (fn. 4) Now the possibility was raised of a joint venture with the county of Middlesex. Strong support for the scheme, even the possibility of financial help, came from Clerkenwell Vestry, and the Clerkenwell architect Alfred Bartholomew busied himself with making plans and estimates. The local advantages were obvious. Aside from the improved transport link, there was the opportunity of clearing a swathe through the tumbledown old properties abounding in this part of Clerkenwell and Holborn and of further enclosing the Fleet. (fn. 5) In March 1833 the Corporation and the Middlesex justices settled on a plan by the county surveyor, William Moseley, which would have taken the road north through Rodney Street in Pentonville and on to Holloway Road. But the project was abandoned owing to the difficulty of raising county finance. (fn. 6) The public authorities having so far failed to make much progress, a joint-stock company (with Elmes as architect and surveyor) was projected to undertake the Farringdon Street extension to Clerkenwell Green with private capital. The return was to come from the leasehold development of houses alongside. But this scheme too came to nothing. (fn. 7)

In the later 1830s the Farringdon Street extension was endorsed by the Parliamentary Select Committee on Metropolis Improvements, full weight being given both to the social and sanitary benefits of the scheme and to the easing of traffic. (As things stood, vehicles going north through the City from Blackfriars Bridge tended to follow a congested route along Old Bailey and through Smithfield to St John Street—making no use of Farringdon Street, which ended with a T-junction at the Holborn end.) (fn. 8) Meanwhile the City Corporation, apparently in anticipation of a state-funded continuation of the road into the further reaches of the Fleet valley, went ahead and in 1837–8 obtained an Act authorizing it to extend Farringdon Street 'towards' Clerkenwell Green. (fn. 9) In 1840, by which time the Corporation had carried out the necessary property acquisition and clearance up to the City boundary, a further Act set up machinery for implementing the next stage, between the City and the Green. Responsibility for this was put in the hands of a 22-strong body of Clerkenwell Improvement Commissioners, mostly drawn from Clerkenwell Vestry but with representatives too from the parishes of St Andrew, Holborn and St Sepulchre Without, through whose territory the route passed. (fn. 10) Plans for the road were drawn up by the Commission's architect and surveyor, R. C. Carpenter (whose father Richard Carpenter was one of the members). He also produced plans and elevations for houses intended to be erected on lease alongside. (fn. 11)

In 1845 the Improvement Commissioners obtained further powers, allowing them to extend the road, on its completion, beyond Clerkenwell Green. (fn. 12) But their activities were undermined by an inability to raise sufficient money. It had originally been intended that they would receive funding via the Treasury, based on the estimated cost of the road as stated to the Select Committee by the Middlesex justices. When this was eventually made available it proved quite inadequate. More was raised by mortgaging the properties acquired by the commissioners, but though this exhausted their credit it was still insufficient. A scheme for raising money through a tontine was abandoned. Having run into the financial sands, and with their statutory powers of compulsory purchase expiring, in 1851 the commissioners bowed out and the entire enterprise was transferred to the City Corporation under new legislation. (fn. 13)

From the Improvement Commission came the original name for the new road, Victoria Street. It was also due to the commission that the road was made 60ft wide (including the footpaths), rather than 50ft as previously intended by the City. In agreeing to widen their own section, the Corporation insisted that the route follow a straight line from Farringdon Street, and so the final form of the present-day road began to take shape. (fn. 14) The next significant change of plan came in 1848, when at the behest of the Corporation and the City Architect, J. B. Bunning, the road was re-aligned to take a 'more easy Curve in to Coppice Row'. Instead of running direct to the Middlesex Sessions House at Clerkenwell Green, it now bypassed the Sessions House, linking up directly with the existing roadway going on to King's Cross—this northern extension being fundamental to the overall success of the road, as the Corporation realized. (fn. 15)

Construction, 1841–56

Work on the new road, supervised by William Mountague, the City Clerk of Works, began late in 1840 or early the following year. By May 1841 the road and new Fleet sewer had reached the City boundary at West Street. In August, Samuel Grimsdell was contracted to make the drains and pavement vaults, and in November attention turned to the question of paving and kerbing the footpaths, so as to facilitate letting the ground for building. This paving work, somewhat delayed by negotiations with the Holborn and Finsbury Commissioners of Sewers (who declined to contribute to the cost), was under way by April the next year; the contractor was James Chadwick of Grosvenor Wharf, Millbank. Further progress was held up by the Improvement Commission's failure to raise the capital for their section. Not only did this leave the ground cleared by the Corporation unusable for an indefinite period, but it cast a blight on the already decrepit property along the remainder of the route and, especially pertinent in view of successive outbreaks of cholera in London, prevented further work on the sewer. This was being aligned to the new road, only a short part of which was to run over the meandering bed of the Fleet. (fn. 16)

Acquisition and demolition resumed, and by August 1845 Grimsdell had completed the vaults on each side of the new road as far as the ground had been cleared: the junction with Peter Street, a turning—subsequently obliterated—on the west side of Turnmill Street just south of Benjamin Street. (fn. 17) Plots to let along the frontage were advertised, (fn. 18) but no takers came forward and at an auction in 1847 no bids reached the reserves. By 1849 it was quite clear that the Improvement Commission had no hope of fulfilling its task. The takeover of the improvement by the City Corporation in 1851 gave new hope, but before much progress could be made plans were upset by proposals for an underground railway between King's Cross and the City, on the line of the new street. (fn. 19)

While the rail scheme was making its way through Parliament, the roadworks were held up. Demolition of houses continued, however, and by 1854, when the line received Parliamentary approval, negotiations were taking place with the railway company for the purchase of land. (fn. 20) Following a change of plan, and an amending Act in 1859, the line was re-routed to run underneath the road as far south as Ray Street, continuing in an open cutting to a terminus on the east side of the road. (fn. 21) In 1860 the Metropolitan Railway purchased all the City Corporation's land on the east side of Farringdon Road (at a cost of about £35,000 an acre). (fn. 22) Construction of the railway took place in 1860–2.

Completion of the next section of the road, to Ray Street, was carried out by the contractor John Jay between December 1855 and August 1856. The work involved raising the levels of the ground—a mixture of alluvial soil and made ground—by as much as 25ft in places, and also clearance of the century-old paupers' graveyard on the west side of Ray Street. (fn. 23) The remains were transferred to a vault on the east side of the new road, itself removed a few years later for the construction of the Metropolitan Railway. (fn. 24) Announcing the opening of the street to carriages after years of delay, the Companion to the Almanac complained about the road levels, apparently chosen with no regard for the City's improvement at Holborn Hill, and blamed the defunct Clerkenwell Improvement Commission for the whole 'ill-managed undertaking'. (fn. 25)

Co-construction with the Metropolitan Railway, 1860–8

The final phase, from Ray Street to Lloyd Baker Street, was carried out in tandem with the construction of the Metropolitan Railway from 1860. No clearance was required at first, as the railway ran directly beneath the road, on the line of the existing roadway along Coppice Row and part of Bagnigge Wells Road. (fn. 26) When additional railway lines were laid in 1864–8, however, all the buildings along the east side of the route north of Ray Street had to be cleared. This stretch of the road was in use by the time the additional lines opened in 1868, though not quite finished until February 1869. The contractors were Sewell & Sons. (fn. 27)

504. Farringdon Road north of Ray Street

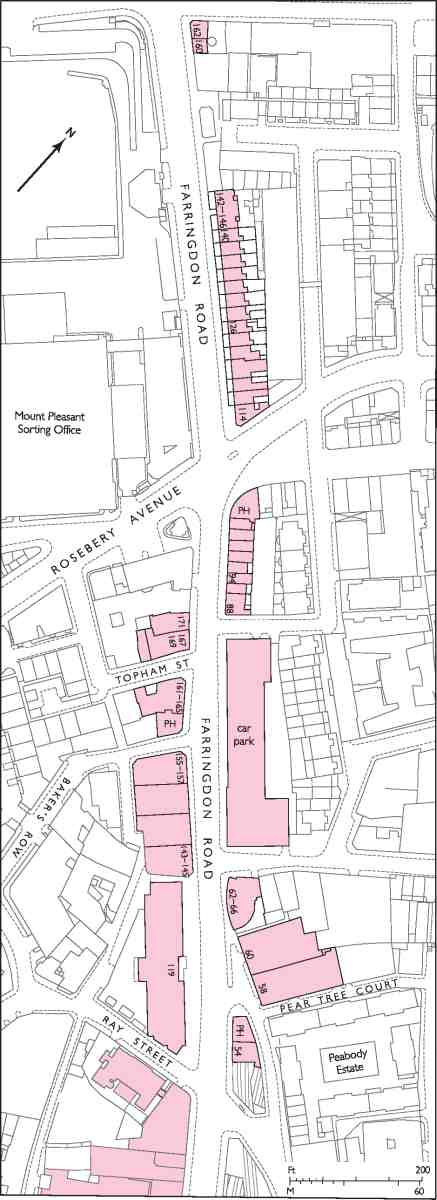

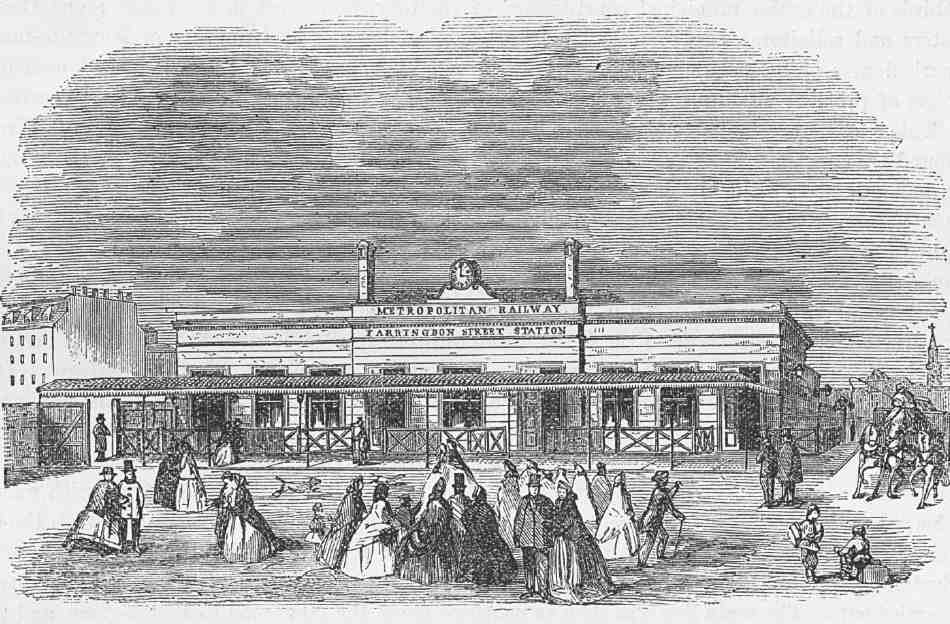

505. Farringdon Road and the Metropolitan Railway, 1868. Looking north from Turnmill Street

The idea of a railway between King's Cross and the City, which had first been suggested in the early years of railway speculation, had no more committed advocate than the City Corporation's solicitor, Charles Pearson. In 1851 Pearson and John Hargrave Stevens junior, one of the City district surveyors, produced plans for reconstructing the road from King's Cross to Farringdon Street with a railway line running beneath to a grand City terminus. This 'Fleet Valley Railway' was successfully opposed in Parliament in 1853 as going against the recommendations of the recent Royal Commission on Metropolitan Termini not to allow main stations so far into the centre of London. But the following year the promoters of the Metropolitan Railway were successful in gaining approval for their not dissimilar scheme, an underground railway from the Great Western terminus at Paddington via the Great Northern's King's Cross terminus to the City. Difficulties in raising capital, partly on account of the Crimean War, delayed the project until the late 1850s. At Pearson's urging, the City Corporation invested heavily in the venture in 1858–9, and in January 1860 excavation at last began. (fn. 28)

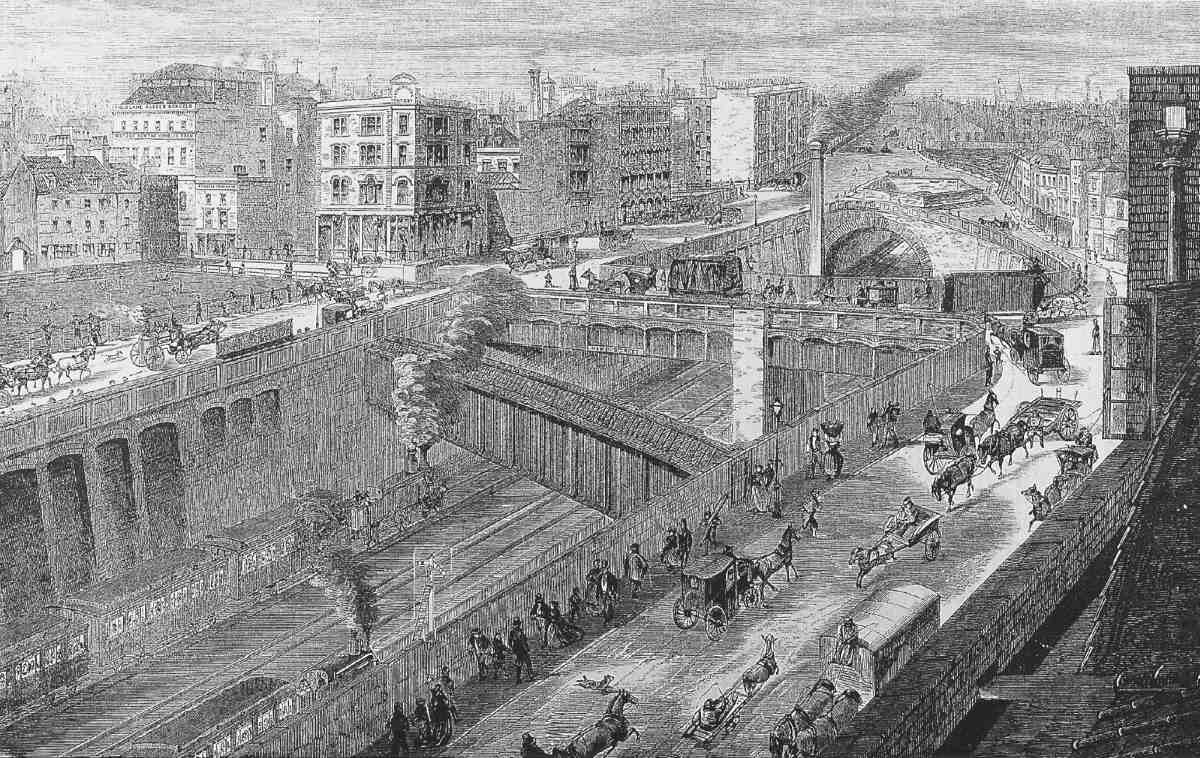

John Fowler acted as chief engineer for the railway company, with Thomas Marr Johnson as resident engineer. The technique used was what came to be called cut-and-cover. As the cutting proceeded, the supporting shores were replaced with brick retaining walls and piers, backed with concrete and—for most of the way—covered over with elliptical brick arches or cast-iron girder roofs. A backfill of concrete, with a coating of asphalt, and earth on top, completed the work. At its southern end, the cutting remained open, crossed by a series of bridges connecting Farringdon Road with the streets on the east side (Ills 505, 506). The brickwork itself, mostly done in white perforated bricks, was of high quality, better than most railway work of the day. (fn. 29) John Jay was awarded the contract for the section east and south of Euston: the route lay through hard London clay and made ground, crossed the Fleet three times and passed through a maze of water pipes, gas pipes and sewers. (fn. 30) In the low-lying land between the parish workhouse and the Sessions House, however, the ground level had to be raised. This was done with earth carted from the embankment of a disused New River Company reservoir at the bottom of Hampstead Road (on the site now occupied by Tolmers Square). (fn. 31)

The work was far from trouble-free. Loss of life was only just avoided in September 1861, when a 55ft-deep shaft in which two dozen or more men were building a section of the tunnel opposite the Cobham's Head public house was flooded by a burst water main. (fn. 32) The Cobham's Head itself, which stood at the corner of Cobham Row and Coppice Row (on the site of Clerkenwell Fire Station) was just one of many buildings which became unsafe because of subsidence caused by the excavations and had to be evacuated: much of the ground in the vicinity consisted of nothing more than a deep layer of ancient rubbish, and buildings crumbled readily. The old inn was reportedly badly cracked and leaning towards the tunnel when the inhabitants were ejected for their own safety by an inspector of lodging-houses in December 1861. Nevertheless it survived until 1866, when it was destroyed by fire. (fn. 33)

506. Farringdon Road and the Metropolitan Railway cutting. View south in 2002

Early in 1862 effluent was said to be leaking out of the Fleet sewer at a rate of several gallons a minute, filling the vaults along the new street for nearly a hundred yards and pooling against the walls of St Peter's Church and Schools in Great Saffron Hill. (fn. 34) In June disaster occurred when a section of the sewer fell in near Ray Street, the tide of sewage inundating the ground on the west side of Farringdon Road and backing up behind the new retaining wall of the railway cutting. Despite concerted efforts over the next couple of days by the railway contractors and the Metropolitan Board of Works (as the new sewers authority), the wall began to fail, shores and scaffolding across the cutting were smashed and the cutting and tunnel as far north as Exmouth Street (Exmouth Market) were flooded. The vault holding the bodies cleared from Ray Street burial ground, which stood exposed on the east side of the cutting, was broken open by shoring which had been laid against it. Blame for the incident clearly lay with the construction of the Fleet sewer, and if anything the incident showed how substantially the railway work itself was being carried out. With the flood temporarily diverted towards the Thames, the sewer was reconstructed, a section of it passing through the railway tunnel in an iron pipe. (fn. 35)

The new line was ceremonially opened in January 1863. But the terminus itself (Farringdon Street Station) was only a temporary one, and the final extent of the line still uncertain. Plans were already in progress for extensions, including one to the London, Chatham & Dover Railway terminus at Blackfriars and another going further east to Moorgate. Such plans for growth, and the increasing use of the line by the expanding suburban networks of the Great Northern and Great Western railways, prompted the building of a second set of tracks from King's Cross to Farringdon Street Station and sidings to the new meat market at Smithfield. These additional lines were solely for the use of the main-line companies (including the Midland Railway, whose terminus at St Pancras opened in July 1868), leaving the Metropolitan's original track free of long-distance passenger and goods trains. The work was carried out by John Kelk (also contractor for the Moorgate extension), with Fowler as engineer. (fn. 36)

507. Shored-up buildings along the route of the Metropolitan Railway at Coppice Row, 1862

The new tracks from King's Cross ran in a second tunnel immediately east of the existing line: a short section of this parallel tunnel had in fact been built at the same time as the original, with this duplication in mind. (fn. 37) Emerging at Ray Street, they crossed under the old line and continued in the cutting to the site of the temporary Farringdon Street Station, where a large goods depot was subsequently built by the Great Northern Railway Co., and where the Smithfield sidings were situated. At Ray Street the Metropolitan Railway was carried over the widened lines on a skew bridge, with the roadway above on Ray Street Bridge (part of the early 1860s work) spanning them both (Ill. 509). The new rail bridge, of latticegirder construction, suffered badly from corrosion and needed extensive renewal by the 1890s. It was finally replaced, using concrete beams and slabs, in 1960. (fn. 38) Further south, there were iron girder bridges at Vine Street and Charles (now the western part of Cowcross) Street, completed in September 1862. (fn. 39)

508. Farringdon Road and the temporary Metropolitan Railway station, seen from the tower of St Andrew's Church, Holborn, 1862. Behind are houses on the east side of Turnmill Street (then partly Cowcross Street). To the east and south of the terminus is a group of mostly industrial buildings in West Street, Black Boy Alley and Sharp's Alley, including Braden's Steam Mills for producing cattle feed. The prominent run of white buildings and the large dark building with the tall chimney are the former works of Galloway & Co., merchants, and Alex. Galloway & Son, engineers. They were then in the occupation of (from left to right): Charles Hancock's West Ham Gutta Percha Co. (with chimney); Field Lane Ragged Schools; and Cornelius Tipple Youngman's paper-bag manufactory

In addition to redirecting sewers, water mains and gas pipes, Fowler and Kelk had to rebuild parts of the existing line and underpin the retaining walls, while at the same time allowing a regular train service to operate. As a result, only a short section could be completed at any one time, and Kelk was penalized for falling behind with the contract. The new lines opened in February 1868, making Farringdon one of the most important stations in London. (fn. 40)

Railway buildings

When the Metropolitan Railway opened early in 1863, it ran to a temporary terminus beside Farringdon Road, west of the present Farringdon Station. The permanent station on the corner of Cowcross Street and Turnmill Street was erected in 1865 and, apart from the entrance block (rebuilt in 1922), the building remains substantially intact today. The old terminus site was redeveloped in the 1870s as the Great Northern Railway Goods Station, with a massive warehouse over the railway lines (now demolished), and a yard and stables south of Cowcross Street (now occupied by offices and shops—Caxton House and Cardinal House, built c. 1960). (fn. 41)

In 1909 the Metropolitan Railway Goods Station was built, north of Vine Street Bridge on the west side of Farringdon Lane. Its capacities were over-stretched within a few years, leading to traffic congestion, but by the late 1920s business had fallen off, owing to competition from road transport. The depot building, with sheer brick to the street and (originally) corrugated iron on the railway side, closed in the 1950s and is now used by London Regional Transport's lifts and escalator engineer as Vine Street Stores. (fn. 42)

509. Crossing of railway lines and bridges outside Farringdon Street Station, 1868

As far back as 1865, an approach was made by the Vestry to the Metropolitan Railway for a station north of Farringdon at Exmouth Street, but the suggestion was rebuffed, on the grounds that it would have required too many steps between street and platforms. Subsequently powers were obtained by the company for opening a station at Mount Pleasant, but these were never acted upon, and Farringdon remains the only railway station in Clerkenwell. (fn. 43)

The temporary station

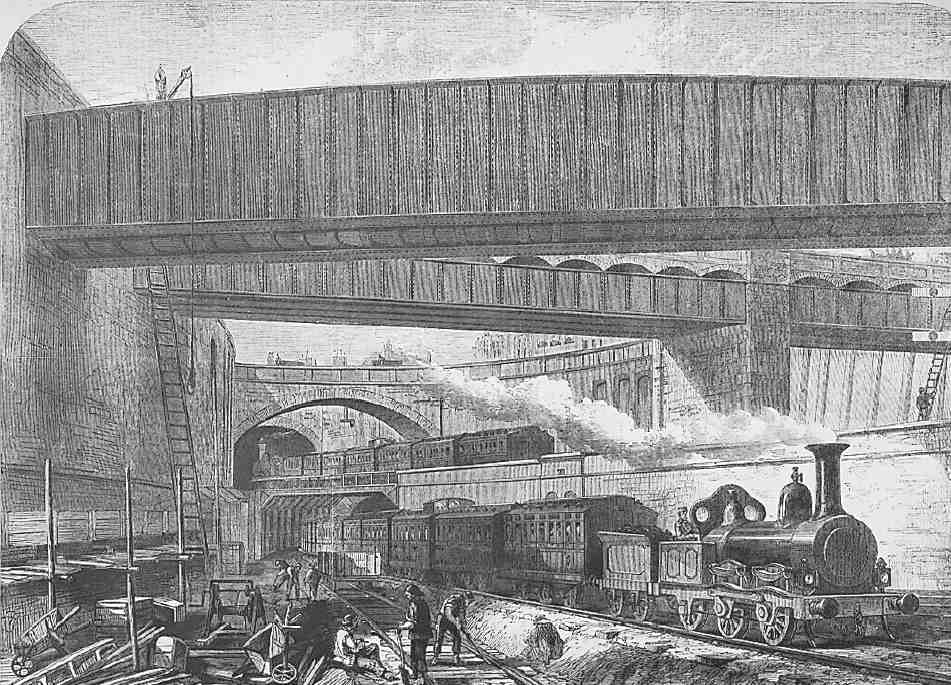

Fowler's plans for the temporary station were finalized early in 1862: Illustration 508 shows the terminus later in the year, with the buildings well advanced. (fn. 44) Along the roadside as far as the corner of West Street, broken only by the turning into Charles Street, is a high brick wall. To the south of Charles Street, at right angles to Farringdon Road, is the entrance building, beyond which are the still far from completed sheds over the platforms, at a lower level and bisected by the bridge forming the western end of Charles Street. Completed in September 1862, the bridge consisted of 'seven ponderous girders' of wrought iron, manufactured by Westwood, Baillie, Campbell & Co., with brick arches between, tied with wrought-iron bands. (fn. 45)

As completed, the main approach to the station was from the south, through a gate a little way along West Street and across an open yard or forecourt adjoining the booking hall. (fn. 46) A contemporary illustration shows this forecourt and additional access at the sides of the station, from Farringdon Road and Charles Street (Ill. 511). It also shows a covered way or veranda along the front of the entrance building and a clock over the parapet. Neither of these features, nor any gate in the wall along Farringdon Road, are shown in another view, published in December 1862, shortly before the rail service opened, and it is not certain if they were indeed added.

510. Farringdon Street Station platforms in 1866

Although temporary, the station was substantial and sufficient, as was acknowledged when the equally wellconstructed temporary Moorgate Station opened in 1865. (fn. 47) The platform sheds comprised side walls built of white perforated brick with blank arcading, and timber queen-post roofs, with central lantern-lights and louvres. The entrance building, presumably built of similar brick to the shed walls, contained a central semi-circular booking office, with the heads of the stairs leading down to the platforms on either side. (fn. 48)

511. The temporary station, c. 1863

To mark the opening of the line in January 1863, a banquet for 700 guests was held in a temporary room erected adjoining the station. This was presumably on the yard between the booking hall and West Street, or the present station site; one report, however, describes the station itself as having been 'fitted up in its whole length … as a dining-hall' for the occasion. (fn. 49)

With the opening of the permanent station, the temporary buildings continued in use serving Great Northern and Great Western trains. The temporary station was finally closed at the end of February 1866, and the site subsequently redeveloped as the Great Northern Railway Goods Station. (fn. 50)

Farringdon Station

Work on the permanent terminus was put in hand soon after the Metropolitan Railway opened. Fowler's plans were ready in January 1863, and John Jay was engaged to carry out the excavations, retaining-wall construction, and extension of the Charles Street bridge. In May, his concern regarding liability for any damage to the houses in Turnmill Street caused Jay to back out, and he was replaced by John Kelk. (fn. 51) The new Farringdon Street Station was under construction by the end of September 1865 and completed by the following February. (fn. 52)

Most of the original building survives, the main exception being the entrance block fronting Charles Street. This was built of yellow brick in the simple Italianate manner adopted for the stations along the Metropolitan Line generally; a few bays are left alongside Turnmill Street (Ill. 512). It consisted of a single storey with a bridge at the back giving access to stairs down to the platforms. There were two booking offices (one for first- and second-class passengers, the other for third-class), and a refreshment room, run by Spiers & Pond, who had established their catering business in Australia in the 1850s, serving golddiggers on the Melbourne and Ballarat Railway. (fn. 53) Only the western half of the booking-office bridge remains (with its iron lattice-work front), the other half having been replaced by an extended circulation space for passengers using the Metropolitan platforms. Two further bridges which originally crossed the station have been removed.

512. Farringdon Street Station, c. 1916. Designed by John Fowler, Metropolitan Railway chief engineer, 1865

Downstairs from the entrance hall, the station is irregular in plan and on a split level, the slightly higher platforms, on the east side, being for the Metropolitan Railway; the western platforms were originally used by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway's trains, running to Blackfriars. The main roof is in two spans, each with shallow iron bowstring trusses, carried on cast-iron columns with curved brackets and at the sides by white brick walls with blank arcading (Ill. 510).

By the First World War the entrance block was in need of replacement. It was too small for the number of travellers, and had very little space for commercial letting. Besides the small Spiers & Pond restaurant, there was a tobacco kiosk, a W. H. Smith's bookstand, and a fruit stall on the pavement outside. Plans for a new two-storey building were drawn up in 1915 under the supervision of Charles Walter Clark, architectural assistant to the Metropolitan's engineer, but work was deferred because of the war and it was not until late 1922 that the rebuilding went ahead. The contractor was W. J. Maddison, of the Minories. (fn. 54)

The new building, not greatly altered since, incorporated four lock-up shops on Cowcross Street, together with a refreshment room for Spiers & Pond, who also took the first floor for a restaurant, large enough for a hundred diners. The booking hall and circulation area were greatly improved in accordance with the latest thinking on crowd control, providing more space for booking and a parcels depot. Externally, it was in the new Metropolitan Railway 'house style'. Broadly Classical in treatment, it is faced in ivory-coloured faience tiling, with Art Deco-ish ornamentation and curved corners for the shops; the restaurant originally had old-fashioned leaded windows (Ill. 513). A frieze and entrance canopy bore the new name of Farringdon and High Holborn Station, chosen to convey an impression of the wide area west of Farringdon Road served by the station. (fn. 55)

513. Farringdon Station in 1923, soon after refronting by Charles Walter Clarke, architect

Clark also designed the matching two-storey range of shops and offices on the opposite side of Cowcross Street (Nos 54–60), built in 1923 by the Unit Construction Co. Ltd of Regent Street (see Ill. 243 on page 193). (fn. 56) In recent years, plans have been put forward to extend the station south of Cowcross Street, demolishing some of the shops there.

Station Chambers at No. 56 Turnmill Street was converted from part of the 1865 station building in 1932 and leased by the architect Samuel A. Spear Yeo for his office. (fn. 57)

Great Northern Railway Goods Station (demolished)

Proposals for a large goods depot at Farringdon Station were put forward in 1864 by William Burchell junior. Burchell's father, with whom he was in partnership, was solicitor to the Metropolitan Railway. The scheme was floated unsuccessfully the following year by the Metropolitan Railway Warehousing Co. Ltd, which was finally wound up in 1872. (fn. 58) Meanwhile, the construction of the additional lines from King's Cross in 1864–8 allowed the Great Northern Railway to begin carrying freight to Farringdon early in 1868, and by 1874 work had begun on a warehouse over the lines, between Farringdon Road and the permanent passenger station.

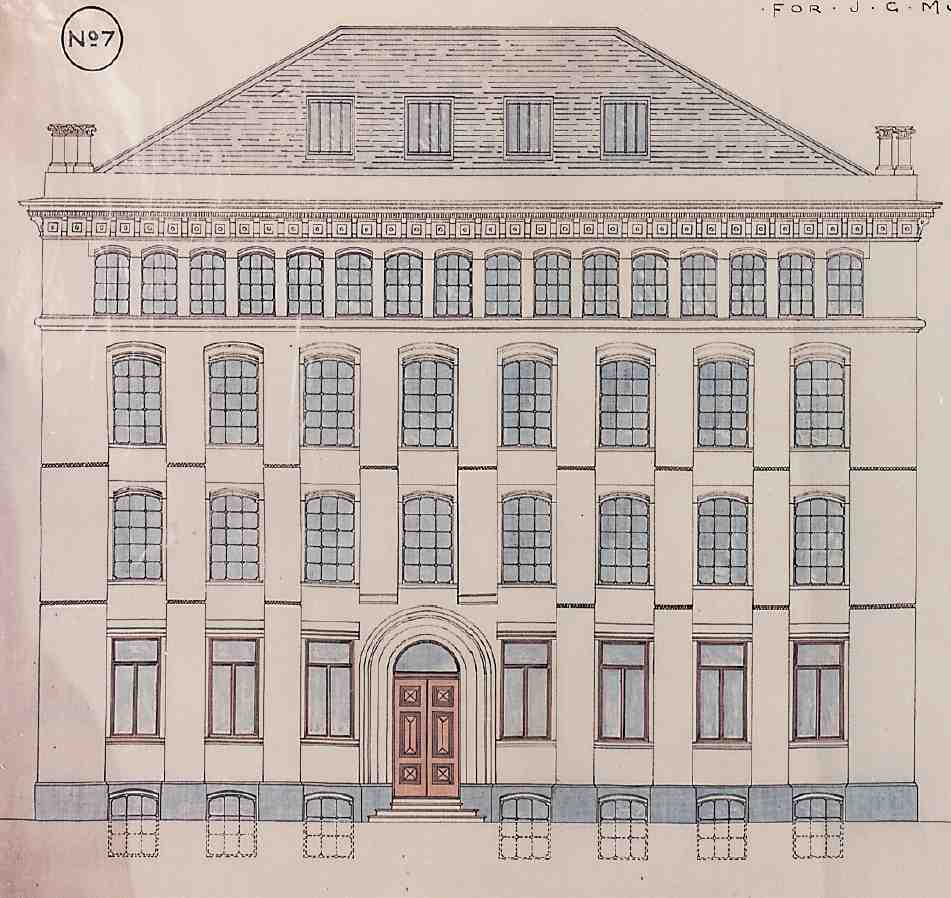

Designed by the GNR chief engineer, Richard Johnson, this block had a frontage to Farringdon Road of over 300ft, rose 60ft above the street level and covered a ground area of some 28,000sq. ft (Ill. 514). South of Charles (Cowcross) Street was the goods station yard, extending for another 200ft, from where a ramp led back under the street to the goods platforms. Building the depot was a considerable project, taking five years to complete and costing £100,000, exclusive of the £40,000 paid for the site. The construction work was undertaken by two main contractors, supervised by a resident engineer, W. Wilkinson. Westwood, Baillie & Co., who supplied the ironwork for the building, carried out the substructure, and upper parts were built in conjunction with them by Kirk & Randall of Woolwich. (fn. 59)

Westwoods' contract involved complex groundwork and reinforcement of the existing structures. The railwaycutting retaining wall alongside Farringdon Road had to be underpinned and strengthened, and the iron columns of the bridge over the lines at Charles Street replaced with brick piers.

The warehouses were carried on a substructure at the railway level comprising piers and arches of Staffordshire blue brick and cast-iron columns, with wrought-iron girders running across. In the upper storeys, the floors were supported on cast-iron columns, or wrought-iron stanchions and box girders where large open areas were required. The floors themselves were constructed on Westwood, Baillie & Co.'s patent corrugated-truss fireproof system, its first major use. This comprised corrugated-iron plates, riveted together and bolted to wrought-iron trusses underneath, and filled on the upper side with concrete and asphalted. The windows were Moline's patent wrought-iron sashes, and the roofs too were of iron construction. For the rest, the warehouses were built of brick, chiefly Burham wire-cut whites. On the street front were dressings of Pether's pressed bricks (made of the same clay as the wire-cut bricks), and window arches of red brick with Portland stone keys.

514. Former Great Northern Railway Goods Station in 1977. Designed by Richard Johnson, GNR chief engineer, 1874–9. Demolished

Goods-handling at the new depot was carried out with hydraulic machinery, including a series of cranes in the basement (the two largest able to raise three tons each), capstans for hauling railway wagons, and hoists to move wagons between the basement and first floor. Two goods lifts of two-ton capacity and four jiggers for loads up to 10cwt served all levels of the building.

At the south end of the block, fronting Cowcross Street, were the depot offices. These were in the same style as the Farringdon Road elevation, and had an additional storey in the form of a mansard (see Ill. 513).

In 1893 the goods yard south of Cowcross Street was improved with the erection of a floor at street level, carried on steel stanchions and girders and with a steel roof over, together with platforms, a traverser way and offices facing Farringdon Station. The work, costing £39,400, was carried out to Johnson's designs by Matthew Pitts of Stanningley, near Leeds. (fn. 60)

Badly damaged at the southern end by bombing in 1941, the goods station (which had belonged since the 1920s to the London & North Eastern Railway) closed in January 1956, remaining derelict thereafter. (fn. 61) The property developers Gable House Estates had acquired the site by October 1987, and the warehouses were demolished in 1988 to make way for offices. The new buildings, two adjoining blocks ranging from three to six storeys, were erected in 1988–92 by Bovis Construction to designs by the Seifert Group. The taller, southern block, originally called Farringdon Court, occupies the site of the old warehouses; the other, Lincoln Place, extends further north over the site of the open railway cutting. Special secondary glazing incorporating steel gauze, and sheets of 6mm galvanized steel behind the external cladding, protect computer equipment from crashing as a result of radio frequency interference caused by trains changing from overhead to third-rail power. (fn. 62)

Dark-glazed and clad in pink and grey panels of polished granite, the development was derided by the critic Hugh Pearman as 'Early Learning centre architecture' and nominated by him as one of the two worst buildings of 1992. (fn. 63)

Between Farringdon Station and the goods depot site, No. 43 Cowcross Street was built about 1891, and first occupied as a tobacconist's shop. (fn. 64)

The pattern of building development, 1864–92

Because of the protracted nature of the road and railway projects, it was many years before the City Corporation was ready for building development to begin. There was a false start in 1856, when John Jay, who as main contractor had already constructed pavement vaults, undertook to develop both sides of the road (which had reached Clerkenwell Green) with warehouses. However, he defaulted on his agreement, and following this failure the City appears to have been reluctant to grant any building leases while improvement works were still in progress. (fn. 65) Accordingly, nothing was built before the temporary Metropolitan Railway station in 1862; in the meantime, all the City's ground on the east side of the road had been sold to the railway company.

In 1864–5, with the City's model dwellings scheme (Corporation Buildings) getting under way, the surplus cleared ground on the west side of the road was divided into parcels and offered on 80-year building leases by public tender. Lessees had the option to buy the freehold (which under the enabling legislation the City had no power to keep permanently, reversions having to be disposed of within five years of buildings being erected). (fn. 66) Buildings had to be completed within twelve months to plans approved by the City Architect and following strict specifications as to the materials used. In addition to a premium, lessees were charged for the costs incurred by the City in constructing the pavement vaults. (fn. 67)

The first commercial developments were immediately south of Corporation Buildings, on the block between Ray Street and Vine Street: a group of warehouses and factories for the printing industry, and a corner pub (No. 95, the Metropolitan Tavern). The remaining frontage here was filled in with warehouses and model dwellings (No. 97, part of Victoria Dwellings in Clerkenwell Road) during the 1880s. Development continued on this side of the road with buildings on several corner sites in the 1870s, the large remaining gaps being filled in, mostly with warehouses, over the following decade. The only noncommercial building here was a drill hall (No. 57A), set behind the warehouses with a cartway entrance from the street: the original idea seems to have been for a cross street at this point, running through to Great Saffron Hill. (fn. 68)

A large plot immediately south of Vine Street was taken in 1864 by Thomas Peet Glaskin, a Hackney builder, but was still vacant in the 1870s when part was appropriated by the Metropolitan Board of Works for the construction of Clerkenwell Road; a warehouse was built on the remaining portion c. 1880. (fn. 69)

Corporation Buildings marked the northernmost clearance area on the west side. In 1883 the demolition of the parish workhouse immediately north of this, on the corner of Baker's Row, opened up another large site for redevelopment. This was temporarily occupied by an iron board school (opened in 1886 and closed on the opening in 1893 of the Hugh Myddelton School in Sans Walk). (fn. 70) In the early 1890s another range of warehouses was built there (Nos 143–157).

Development on the Metropolitan Railway's land along the east side of the road took place from 1872 and, except for the Peabody Buildings site and No. 58, was complete by the end of the decade. The first buildings to be erected formed a disparate sequence: Robson's coach-works at No. 60, Orrin & Geer's bookbinding works and warehouse at Nos 62–66, the model dwellings comprising Farringdon Road Buildings, and a terrace of houses and shops. More houses and shops followed, taking up almost the whole of the west side of the street from Vineyard Walk to Lloyd Baker Street. In the mid-1870s a couple of buildings, Nos 54 and 56, the latter a pub, the Butcher's Arms, were erected over the southern end of the Metropolitan Railway eastern tunnel. Further south the open cutting precluded much development, and the only buildings erected here over the tracks were the goods depots of the Great Northern and Metropolitan railways (1874–8 and 1909). East of the railway cutting, some old buildings survived along part of Ray Street (now the southern half of Farringdon Lane). These were gradually replaced with commercial and industrial buildings from the mid-1870s to the 1920s. The White Swan public house at No. 28 was rebuilt about 1896. (fn. 71) The rebuilding of Nos 14–16 in 1923–4 led to the rediscovery of the ancient Clerks' Well, which was left visible through a window at street level. (fn. 72)

The following schedule summarizes building development in 1864–97, together with first occupants or uses where known. Numbering (No. 89 seems never to have been used) is as allocated in 1883, 1889 and 1898. (fn. 73)

West Side (to Baker's Row)

No. 1 (demolished). 1875, tobacco factory. G. B. Williams, architect, for A. Burton. First occupants: Pritchard & Burton, tobacco manufacturers (fn. 74)

No. 3 (demolished). 1875, granary. Edward H. Badger, architect, for G. S. Mumford. First occupants: Peter Mumford & Son, flour factors (fn. 75)

No. 5 (demolished). 1875, warehouse. Builder and building lessee Samuel Sansom, builder and architectural sculptor. (fn. 76) First occupant: Durable Patent Roller Composition Co.

No. 7 (demolished). c. 1870, warehouse. (fn. 77) First occupants: Dresser & Holme, merchants

Nos 9–13 (demolished). c. 1874–6, warehouses. Peter Dollar, architect, for Thaddeus Hyatt, pavement-light manufacturer (fn. 78)

No. 15 (demolished). c. 1875, warehouse. (fn. 79) First occupants: Henry Bird, egg importer; Joseph Izod, fancy goods importer

No. 17 (demolished). c. 1876, warehouse. Edward Withers, builder and lessee. (fn. 80) First occupant: A. J. White, patent medicine manufacturer

No. 19 (demolished). c. 1875, warehouse. Edward Withers, builder and lessee. (fn. 81) First occupants: Vaughan & Brown, art metal workers

Nos 21–23 (demolished). 1870–1, warehouse. First lessees Robert Frederick Sandon and Alfred George Sandon. (fn. 82) First occupants: Sidney Williams, picture-frame maker (21); J. & W. B. Smith, glass manufacturers (23)

Nos 25–27 (rebuilt behind façade). 1873–5, banknote printing works. Arding & Bond, architects, for Bradbury, Wilkinson & Co., engravers

No. 29 (demolished). 1870–1, factory. E. A. Gruning, architect, for Frederick Giesler Lloyd of Sales, Pollard, Lloyd & Co., tobacco manufacturers. (fn. 83)

Nos 31–35 (demolished). 1880, warehouses. Lamb & Church, architects, for Edward Withers, builder. (fn. 84) First occupants: Food of Health Restaurant (31); Anglo American Drug Co. Ltd (33); Beckwith & Co., clothworkers (35)

Nos 37–41 (No. 37 demolished). 1880, warehouses. Lamb & Church, architects, for Edward Withers, builder. First occupants: Brown, Lyman & Co., patent medicine warehousemen; Vogeler & Co., patent medicine vendors (39); Hop Bitters Co. (41)

Nos 43–47. 1883, warehouses. W. D. Church, architect, for Edward Withers, builder. First occupants: Bromhead- Tester Manufacturing & Trading Co. Ltd (43); George Heath & Co., manufacturing jewellers (43); E. Maurice & Co., clock manufacturers (43); Charles A. Vogeler Co., patent medicine manufacturers (45); Ellis & Co. Ltd, bicycle manufacturers (47)

Nos 49–73. 1885–7, warehouses. William Dunk & John Mease Geden, architects, for William Stubbs, general contractor. (fn. 85) First occupants: Pearce's Dining Rooms Ltd (49); George Whight & Co., sewing machine makers (51); Whight & Mann, sewing machine makers; Henry Parkes Skidmore, tube maker (57); John Fogg Shorey, manufacturing chemist (57); Willard Oliver Felt, mechanical engineer (63)

No. 57A, and No. 39 Saffron Hill. 1888, drill hall and caretaker's house, etc. Alfred J. Hopkins, architect, for 2nd City of London Rifle Volunteers. (fn. 86)

No. 75 (demolished). 1875, warehouse. John Wimble, architect, for William Mather, wholesale druggist. (fn. 87)

Nos 77–79. 1882–3, showrooms, offices and workshops. William Brass, builder, for William Marshall & Co. of Gainsborough, engineers. (fn. 88) Exterior incorporates cast iron by H. Young & Co. of Eccleston Iron Works, Pimlico

No. 81 (demolished). 1877, warehouse/factory. Lamb & Church, architects, for Sherriff Martin (trading as Henry Williamson), jet ornament manufacturer (fn. 89)

Nos 83–87 (demolished). 1887, warehousing. J. & A. Bull, architects. (fn. 90) First occupants: Falk, Stadelmann & Co., glass manufacturers and importers of gas-fittings, etc

Nos 91–93 (demolished). 1880, warehouse. Henry E. Wood, architect, for John Gloag Murdoch, publisher and bookbinder

No. 95 (demolished). c. 1864–5, public house (Metropolitan Tavern)

No. 97 (demolished). c. 1884. Model dwellings (part of Victoria Dwellings in Clerkenwell Road). Built for Soho, Clerkenwell & General Industrial Dwellings Co. Ltd (fn. 91)

Nos 99–101 & 105–107. 1887, warehouses. John Grover & Son, builders, for Alfred Brown, woollen draper. (fn. 92) First occupants: Wanzer & Defries Patent Safety Lamp Manufacturing Co. Ltd (101); Vicars & Poirson, embroidery designers (105–107)

No. 103 (partly demolished). 1865, factory with offices, shop and dwelling. John Butler, architect, for J. & R. M. Wood & Co., type-founders and printing-press makers (fn. 93)

Nos 109–111. 1865, warehouses. Henry Jarvis, architect, for William Dickes, artist and chromolithographer

Nos 113–117, and Nos 1–7 Ray Street. 1864–8, warehouses and type-foundry. Arding & Bond, architects, for James Figgins, type-founder

Nos 119–141 and Corporation Buildings (demolished). 1864–5 and 1879–80, shops and model dwellings. Alfred Allen and Horace Jones, architects, for City of London Corporation. First occupants of shops: greengrocer; confectioner; bootmaker; milliner; Aerated Bread Co.; coffee-rooms; tailors; beer retailer; furniture dealer; grocer; printer; looking-glass maker

Nos 143–157. 1894–7, warehouses. Alfred Waterman, architect, for Nathaniel Fortescue, builder. First occupants: Michael Henry Nathan & Co., Christmas card publishers (143); J. G. Childs & Co., printer's ink makers (145); HM Works & Public Buildings Stores (147); Edward Langridge & Co., engravers (147); Gormully & Jeffery Manufacturing Co., cycle manufacturers (147–149); Max Krauss, manufacturing stationer (151); R. Maples, Moffat & Son, clock importers (153); Monarch Cycle Co. (155); General Post Office Stores

East Side and Farringdon Lane

Great Northern Railway Goods Station (demolished). 1874–8. Richard Johnson, engineer

Nos 18–20 Farringdon Lane. 1894, warehouses. Lewis Solomon, architect. First occupant: Thomas Glover & Co., gas-meter makers (fn. 94)

Nos 22–24 Farringdon Lane. c. 1884–6, warehouse. First occupant: Thomas Joseph Griffiths, earthenware dealer

No. 34 Farringdon Lane. 1875, warehouse. Rowland Plumbe, architect, for John Greenwood & Sons, clock and watch manufacturers and importers

Nos 54, 56 Farringdon Lane. 1874–5, warehouse and public house (Butchers' Arms, now Betsey Trotwood). Built for John Earley Cook of Knowle Hill, Cobham. (fn. 95) First occupant (54): Richard Ambridge, earthenware dealer

No. 58. 1883–4, ice factory. John Grover, builder, for Vacuum Pump & Ice Machine Co. Ltd (fn. 96)

No. 60. 1875, coach-building works. Probably by J. M. Macey, builder, for Thomas Charles Robson, wheelwright (fn. 97)

Nos 62–66 (demolished). 1872, factory. W. Seckham Witherington, architect, for Orrin & Geer, bookbinders (fn. 98)

Nos 68–86 and Farringdon Road Buildings (demolished). 1872–4, shops and model dwellings. Frederic Chancellor, architect, for Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes. First occupants (shops): wine merchant; barrel-organ builders; surgeon; greengrocer; dairy; oilman; coal & charcoal merchants; pork butcher

Nos 88–112, and No. 2 Exmouth Market (Nos 108–112 demolished). 1872–3, houses with shops, and public house. Rowland Plumbe, architect, for George Day, builder

Nos 114–152 (Nos 142–152 demolished). 1874–5, houses and shops. Walter William Wheeler, builder. No. 114 altered and extended by London County Council 1896 to provide shop fronting Rosebery Avenue

Nos 154–156 (demolished). Mid-1870s, houses. [?] Walter William Wheeler, builder

No. 158 (demolished). c. 1878, warehouse. Built for James Soanes, waste-paper dealer. (fn. 99) First occupants: Eley Brothers Ltd, ammunition manufacturers (fn. 100)

Nos 160–162. Mid-1870s, houses. Walter William Wheeler, builder (fn. 101)

Nos 164–170 (demolished). Mid- 1870s, houses and shops. Walter William Wheeler, Arthur Mazzini Wheeler, William Warren, builders (fn. 102)

Social impact and social housing

The populous and densely built-up area through which much of Farringdon Road was to pass had a long history of insalubrity. Many of the buildings were ancient and dilapidated, trades and industries included some of the most noxious character, and the inhabitants were predominantly poor and deprived. It was also associated with crime and prostitution. In West Street in 1844, for instance, all but one of the houses were said to have been for many years brothels 'of the worst description'. (fn. 103) Moving sluggishly through its centre was the Fleet ditch, the silted-up repository of waste, from domestic sewage to refuse from slaughterhouses and rendering works.

Although the squalid and vicious nature of the district provided a convenient argument in justification of the road scheme, little consideration was given to the impact of the clearance on the existing inhabitants and local businesses. The displaced people were absorbed into nearby districts, contributing particularly to the social deterioration of Pentonville. As for the factories and works, there is evidence that some removed to the nearest available undeveloped ground, north of King's Cross in Maiden Lane and 'Belle Isle'. Others moved further afield. Charles Braden, the cattle-feed manufacturer whose premises (actually cleared for the Holborn Valley, not the Farringdon Road, improvement) are shown in Illustration 508, moved to Bermondsey. (fn. 104)

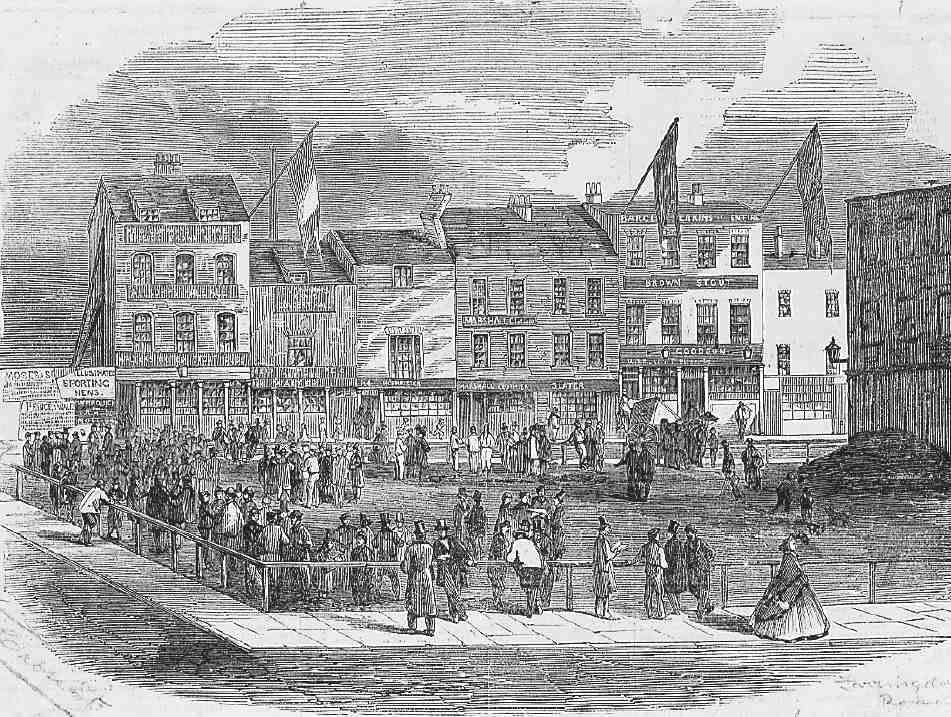

The cleared sites attracted their own temporary society. Early on, congregations of boys and other idlers became a nuisance. By the 1860s the 'Farringdon Street Wastes', or 'The Ruins', as the sites were known, had become a well-known gathering place for betting men, and steps had to be taken by the City to remove them (Ill. 515). (fn. 105) Parts of the vacant land were let on a temporary basis to contractors working in the area, such as Mowlems, who secured the contract for cleaning and maintaining the new road. (fn. 106)

It was not for a decade after clearance began that the subject of social housing provision seems to have been considered at all. A clause in the 1851 Clerkenwell Improvement Act (which transferred control of the entire improvement scheme to the City) authorized the City Corporation to build dwellings for the poor, either on the cleared land or sites bought elsewhere for the purpose. There was, however, no obligation placed on it to do so.

515. 'The Ruins', Farringdon Road, in 1863. The site is now occupied by Nos 29–43 Farringdon Road, the side street at the left being Charles (now Greville) Street, not Cross Street, as marked on the engraving. Behind are buildings in Great Saffron Hill

In the mid- 1850s the Corporation did begin to stir itself to action. Model dwellings in London were investigated, funds allocated, a site on the west side of Turnmill Street was acquired and cleared, and plans were prepared by the City Architect, J. B. Bunning. The proposed dwellings were to have accommodated eighty small and twenty large families, with 'sleeping apartments' for 105 single people of each sex. An alternative arrangement provided for family accommodation only, and included twenty shops. Doubts as to the financial viability of the scheme, prompted by the disappointing returns so far obtained by the Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes from their property, caused the scheme to be abruptly dropped. (fn. 107) A few years later the Turnmill Street site was sold to the Metropolitan Railway.

When the subject was revived in 1863 the agenda was different. Thanks to the efforts of the philanthropist (Sir) Sydney Waterlow, a Common Councilman and later Alderman, the Corporation had been persuaded to consider housing from a moral rather than business standpoint. Building homes for the poor might lose money, but it would do something to offset the problems brought about by large-scale improvement schemes. (fn. 108) Waterlow had recently built, at his own expense, a remunerative block of model dwellings in Mark Street, Finsbury (Langbourne Buildings), and in 1863 founded the Improved Industrial Dwellings Co. to carry out further developments. He argued convincingly that the Corporation should assist those whose homes had been destroyed. (fn. 109)

The result was Corporation Buildings, erected in the mid-1860s. Farringdon Road Buildings, erected by the Metropolitan Association, followed in the 1870s, nearly opposite the earlier blocks. Two other large groups of model dwellings with frontages to Farringdon Road were built later on, in the early 1880s. The Peabody Trust (which had attempted to obtain a site in Farringdon Road in 1863) built on the large Pear Tree Court site between Clerkenwell Close and Farringdon Lane. (fn. 110) The other development (mostly outside Clerkenwell in the Liberty of Saffron Hill) was Victoria Dwellings in Clerkenwell Road, one block of which fronted Farringdon Road at No. 97.

Corporation Buildings (demolished)

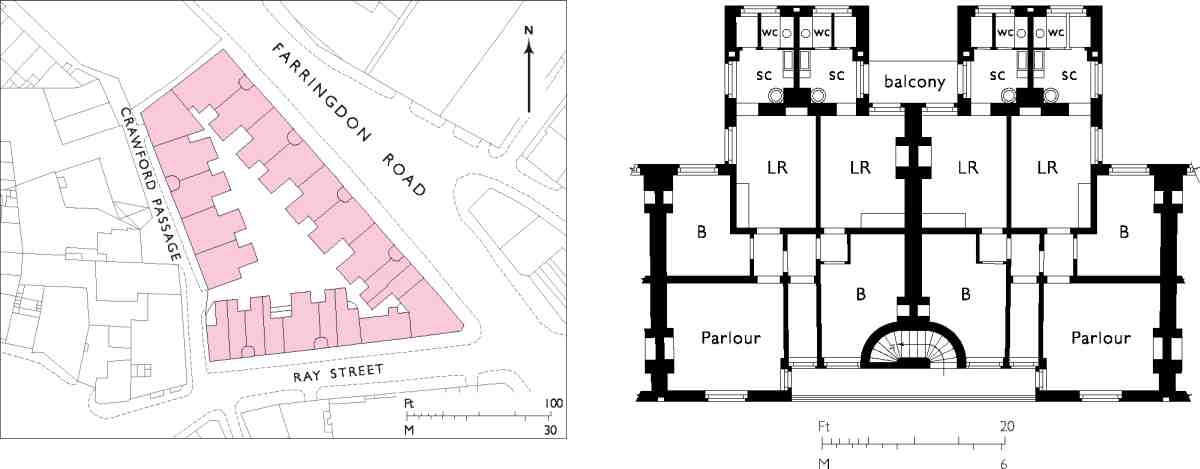

The City's model dwellings, Corporation Buildings, were not only a pioneering venture for the Corporation itself, but the first 'council housing' to be provided in England. They were built in 1864–5, and the site—the corner on the north side of Ray Street, now occupied by the offices of the Guardian (see page 383)—was the first to be developed along the new Farringdon Road.

Plans for the buildings were drawn up in 1863–4 by Alfred Allen, chief clerk in the City Architect's department, who had taken over most of the running of the office on account of the illness and resignation of J. B. Bunning. (fn. 111) His façades, designed 'with strict regard to economy', were modified at a late stage by Bunning's successor, Horace Jones, who realized that a slightly more ornamental building would help attract developers to Farringdon Road, and 'ultimately prove the truest economy'. (fn. 112) The scheme incorporated a row of shops along the main front and warehouse space in the basements: these features were seen by Allen as of some importance, helping to harmonize the blocks with the intended largely commercial character of the road, as well as providing a financial return. The buildings were erected by Browne & Robinson, of Worship Street, Finsbury, at a cost of just over £37,000. (fn. 113) Many dwellings were occupied before the whole development was finished. (fn. 114)

Jones's modifications apart, in general appearance, as in planning, Corporation Buildings were very similar to the Mark Street dwellings erected by Sydney Waterlow. These had been designed by another Worship Street builder, Matthew Allen, but derived from the type devised for Prince Albert by Henry Roberts, which had formed part of the Great Exhibition.

The nature of the site, with frontages to Farringdon Road, Ray Street and Compton Passage, allowed the blocks to be grouped face-outwards around a courtyard (Ills 516, 517). Accommodation was provided for 168 families in a combination of two- and three-room tenements. By the standards of the day, the accommodation was good, each tenement having its own scullery, WC, coal store, and access to a dust-shoot. There were fireplaces and ventilators (linked to a shaft running through the chimney stacks) in all rooms. The roofs were flat and intended for recreation and clothes-drying. (fn. 115) Iron guards were fitted to prevent children climbing from block to block, following a fatal accident in 1868. (fn. 116)

516. Corporation Buildings, Farringdon Road, 1865. Alfred Allen and Horace Jones, architects. Demolished

With an eye to future commercial development, the very corner of the site was left vacant, but it was eventu ally utilized, in 1879–80, for more dwellings, helping to meet the housing need brought about by the Corporation's Holborn Valley improvement. This extra block, providing 15 new tenements at a cost of just over £5,000, was designed by Jones and constructed by T. W. Phelps & T. Bisiker. (fn. 117)

517. Corporation Buildings, Farringdon Road, site plan and upper-floor plan of typical block

Beyond the means of the very poor, the new dwellings were eagerly sought after and occupied mostly by respectably employed working men, including many in the local printing and brewing trades, railwaymen, and a number of white-collar workers. (fn. 118)

In poor condition and considered obsolescent, Corporation Buildings were demolished in 1970. (fn. 119)

Nos 68–86, Farringdon Road Buildings (demolished)

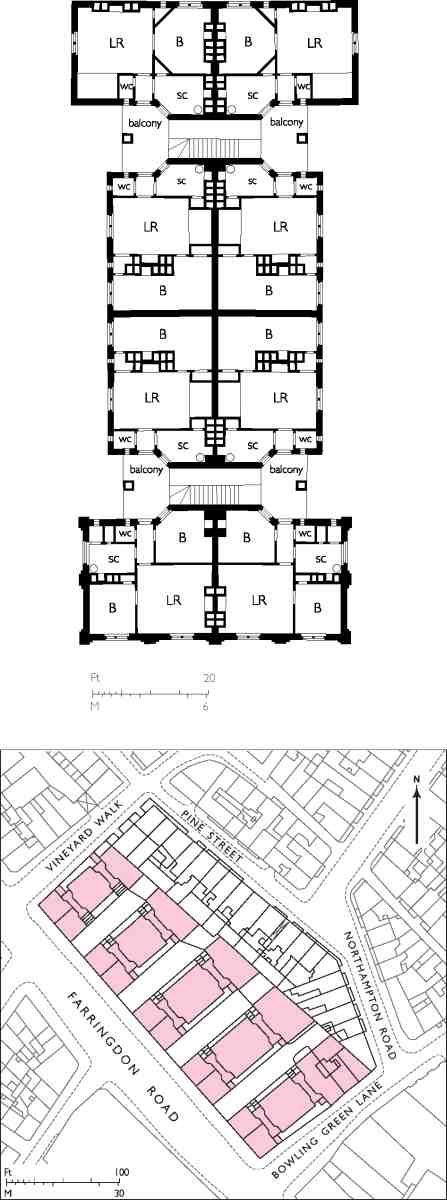

These buildings stood on the east side of Farringdon Road between Bowling Green Lane and Vineyard Walk. They were erected in 1872–4 by the Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes, one of the oldest-established of the model-dwellings companies. Designed by the architect Frederic Chancellor, they were planned along novel lines, embodying ideas long advocated by Charles Gatliff, the Association's secretary. Working-class dwellings, argued Gatliff, had to be built to a high density, both to take account of the high land values in the inner city and to reflect the actual rather than supposed needs of families. This meant tall buildings, with flats containing one or two bedrooms rather than the three conventionally regarded as necessary—third bedrooms being superfluous to many working-class parents, whose younger children often slept in the main living-room. (fn. 120) Farringdon Road Buildings were erected by James Brown of Finsbury Pavement, a builder and contractor with brickworks at Braintree and Chelmsford, whose tender of £39,360 was accepted in November 1872. (fn. 121) The dwellings were formally opened on 13 November 1874 by the Home Secretary, Richard Cross, whose Artisans' Dwellings Act was passed the following year. (fn. 122)

Rather than a long double range of dwellings, with the road on one side and a yard on the other, as originally intended, Chancellor decided on five parallel blocks at right angles to the road, with 20ft courtyards or playgrounds between (Ill. 519). Each block was of six storeys plus basement, and included two shops on Farringdon Road, in the manner of the City's earlier Corporation Buildings. Several advantages were claimed for this arrangement, including an increased density of dwellings on the site, and protection from the spread of fire. The basements were used partly for dwellings, partly as cellars for the shops. Each block contained fifty-two tenements, comprising 10 three-room, 14 two-room and 28 one-room apartments, all with a WC, pantry, and scullery, the whole development giving accommodation to well over a thousand people. Sleeping accommodation was included in the living-rooms of some tenements by means of alcoves for beds—a feature already adopted at Corporation Buildings.

The flats were arranged (Ill. 519) on what Chancellor called the 'Balcony plan', which sought to avoid the drawbacks of the existing types of block dwelling: the staircaseaccess type, where staircases proliferated or, as in Corporation Buildings, unduly affected the internal layout; and the loss of privacy (and light) experienced in gallery-access flats, where neighbouring tenants going to and fro passed right in front of the windows. His solution was to group four flats around each staircase in two pairs, each pair with its own balcony. Privacy and security were increased by providing iron gates at the entrance passages to each flat. Chancellor thought the balconies would not only increase ventilation, but allow the inhabitants to express (and improve) themselves by cultivating flowers there: 'I do not believe that a man who is fond of his flowers could ever thrash his wife, or that a wife who takes a pride in her flowers will ever have a slovenly and untidy dwelling'. (fn. 123)

518. Farringdon Road Buildings from the north-west, early 1970s. Frederic Chancellor, architect, 1872–4. Demolished

The accommodation of the individual flats was also informed by Chancellor's view of the importance of privacy. Each was fully self-contained, for, as he put it, shared wash-houses and WCs were 'a constant source of quarrelling and illwill', and 'loss of modesty and self-respect may in countless cases be first traced to the necessity of using in common one closet by two or more families'. (fn. 124)

Rooms were ventilated by means of air-bricks opening on to flues—which some tenants immediately covered up. (fn. 125)

The floors were constructed with rolled-iron joists set in coke-breeze and Portland cement concrete, the relatively cheap and fireproof material employed by Sydney Waterlow's builder Matthew Allen, and used by him in Waterlow's Langbourne Buildings and in Waterlow & Sons' factory in Hill Street, Finsbury. (fn. 126)

519. Farringdon Road Buildings, site plan and upper-floor plan of typical block

Externally, the blocks were fairly plain, with façades of yellow stock brick, red-brick banding, and cills of the same concrete used for the floors. There was a small amount of ornamentation—a machicolated cornice with shields, and statues or heraldic beasts against the gable surmounting each block (Ill. 518). Asphalted flat roofs provided space for drying clothes and beating carpets, as well as recreation.

From the start, the flats were 'highly appreciated' by the tenants, typically general labourers, warehousemen, and porters; because of the high proportion of one-bedroom flats many were single men. (fn. 127) Although criticisms were made on sanitary grounds, the new buildings were generally well-received. Nevertheless, they came to typify what were widely seen as the worst features of block dwellings, their ugliness and supposedly dehumanising scale: What terrible barracks, those Farringdon Road buildings! Vast, sheer walls, unbroken by even an attempt at ornament; row above row of windows in the mud-coloured surface, upwards, upwards, lifeless eyes, murky openings that tell of bareness, disorder, comfortlessness within … Acres of these edifices … millions of tons of brute brick and mortar, crushing the spirit as you gaze. Barracks, in truth; housing for the army of industrialism … (fn. 128)

Farringdon Road Buildings were declared unfit for human habitation in 1968 by the Greater London Council, and demolished in 1976. (fn. 129) Their site is now occupied by a multi-storey car park erected c. 1989–90 for National Car Parks. (fn. 130)

Commercial architecture in Farringdon Road, 1860s–90s

The commercial buildings forming the larger part of the nineteenth-century development along Farringdon Road fall into two main categories: the comparatively large and sometimes ornate buildings specially erected for particular firms, often connected with the printing trades; and the creations of the speculative builder.

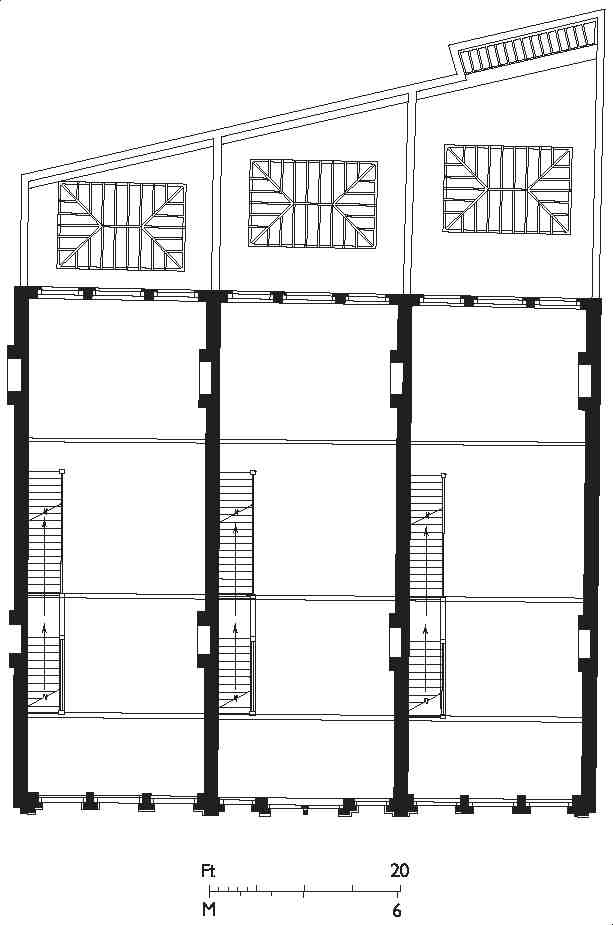

Built in groups of two or more, the speculative buildings were general-purpose commercial premises, suitable as warehouses, showrooms, offices and factories. They were effectively terraced, each unit having a narrow frontage no wider than that of a good-sized terrace-house. Where the depth of the plot permitted, as on the west side of the road between Charterhouse Street and Charles (now Greville) Street, there was rear access, in this case from Great Saffron Hill. Elsewhere, as in the strip immediately to the north, this was not possible and natural light at the back of the premises was achieved by stepping back the upper floors, the rear ground floor being lit with a skylight. Typically, fireplaces were set in one party wall and a simple wooden staircase against the other (Ill. 520).

These terrace-warehouses were presumably designed in this way at least partly for reasons of conservatism, replicating the narrow premises on older streets. With a plentiful supply of small businesses, such small units must also have presented a relatively low risk to the speculator, and enabled part of a development to be let before the rest was complete. There was also the advantage that individual floors within the unit could be let or sub-let, giving flexibility to both landlord and tenants.

520. Nos 43–47 Farringdon Road, first-floor plan. W. D. Church, architect, 1883

Nos 39–73 form the greater part of a row of these speculative warehouses built in stages between 1880 and 1887: four more, at Nos 31–37, have been demolished (Ills 521, 529). Another example of the genre is the range at Nos 143–157, erected in 1894–7 on the site of Clerkenwell Workhouse (Ill. 522). This was designed by Alfred Waterman for Nathaniel Fortescue, a Hackney builder-developer, on lease from Holborn Poor Law Union. The mansard floor dates from a refurbishment of the late 1970s. (fn. 131)

521. No. 45 Farringdon Road, keystone head, 2007. W. D. Church, architect, 1883

The early development of Farringdon Road coincided with the vogue for Venetian Gothic as a suitable style for commercial buildings, given its mercantile associations. It was not used very widely here, but there are a few good examples. Nos 109–111, in red brick and Portland stone, were built in 1865 for the artist, engraver and chromolithographer William Dickes (Ill. 526). They were designed by Henry Jarvis, and built by William Henshaw of City Road Basin; the carving was by William Plows. The buildings originally comprised two warehouses with a large machinery room at the rear. (fn. 132) Nos 25–27 (1873–5), on the corner of Greville Street, was designed by Arding & Bond as a banknote printing works; it was rebuilt behind the original façade c. 1990, with the addition of a mansard and corner turret (Ill. 531). (fn. 133)

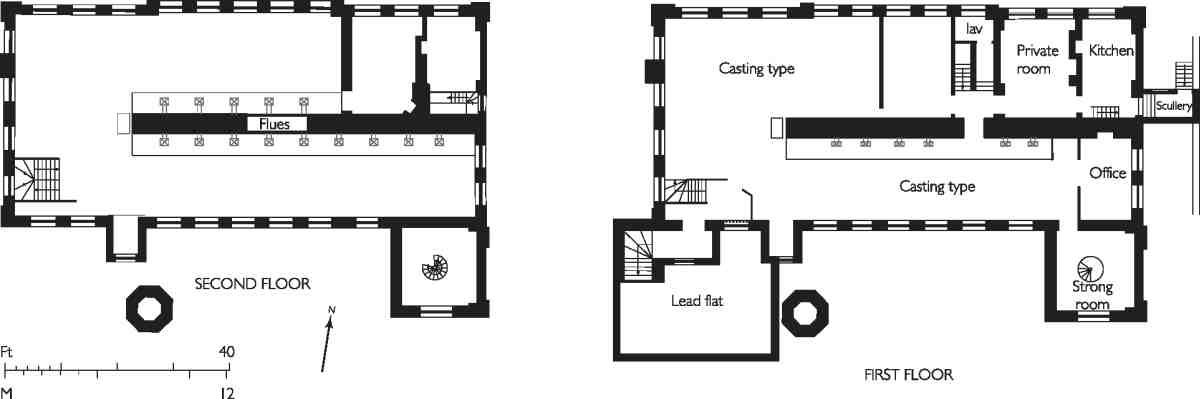

In contrast to these decorative but anonymous-looking buildings is another warehouse inspired by North Italian Gothic, No. 34 Farringdon Lane, which has a highly individualized façade (Ill. 525). Designed by the architect Rowland Plumbe, this was built in 1875 for the clock- and watchmakers and importers John Greenwood & Sons, whose old premises in St John's Square were pulled down for the making of Clerkenwell Road. The front is a showy design, executed in stock and rubbed brick, stucco and Portland and Bath stone. As well as having a large clock in the gable, it is decorated with symbols of time such as the hour-glass, sundial, sickle and serpent. The Greenwood arms and motto ut prosim ('that I may be of use') also appear, and the family theme is continued in the inscription on the foundation stone, recording that it was laid by Greenwood's granddaughter. In construction and layout the building is conventional, with large open rooms, the floors carried on timber joists and iron columns (Ill. 523). The basement was intended for packing, the ground and first floors for showrooms, and the upper floors for warehousing; a detached range at the rear comprised a workshop, stables and house. (fn. 134)

522. Nos 143–157 Farringdon Road in 1988. Alfred Waterman, architect, 1894–7

523. No. 34 Farringdon Lane, section and plan c. 1912

524. Nos 58 and 60 Farringdon Road in 2007, right to left

Commercial architecture in Farringdon Road

525. No. 34 Farringdon Lane in 2006. Rowland Plumbe, architect, 1875

526. Nos 109–111 in 2007. Henry Jarvis, architect, 1865

527. Nos 77–79 in 2007. William Brass, builder, 1882–3

528. No. 103 in 2007. John Butler, architect, 1865

529. Nos 29–47 (left to right) in 2007. Nos 39–41 (with red awnings), Lamb & Church, architects, 1880; Nos 43–47, W. D. Church, architect, 1883

530. Nos 91–93 in 2007. Fuller, Horsey, Sons & Cassell, architects, 1923

531. Nos 25–27 in 2007. Arding & Bond, architects, 1873–5; Simon Smith & Michael Brooke Architects, c. 1990

532. V. & J. Figgins's warehouses and foundry in 1988

533. Detail of monogram on foundry railings, 2006

Two other specially commissioned industrial buildings on the east side of Farringdon Road are Nos 58 and 60 (Ill. 524). No. 58, of white brick, in a round-arched, Italianate style, was erected in 1883–4 as an ice factory for the short-lived Vacuum Pump and Ice Machine Co. Ltd. The builder was John Grover of Wilton Works, New North Road. (fn. 135) No. 60, now remodelled as the Newsroom (see below) is essentially Georgian in style. It was built in 1875 as a wheel and coach works for Thomas Charles Robson and remained in use by the family firm, latterly makers of commercial vehicle bodies, until 1971. (fn. 136)

534. Rear view of former foundry at Nos 3–7 Ray Street in 1994

535. V. & J. Figgins's type foundry, Nos 3–7 Ray Street, first- and second-floor plans in the 1890s

The most monumental of the surviving Victorian commercial buildings in Farringdon Road are also the earliest, and give an impression of how the road generally might have looked had the initial impetus in development been sustained through the difficult financial period in the late 1860s. These buildings, at the corner of Ray Street, were erected for the type-founder James Figgins as printingmaterials warehouses and a type-foundry (Ills 532, 534, 535). The architects were Arding & Bond, the contractors Browne & Robinson of Worship Street. (fn. 137) The typefoundry (Nos 3–7 Ray Street) was erected in 1864–5, and the warehouses (Nos 113–117 Farringdon Road) in 1868; Browne & Robinson were again the builders. (fn. 138)

536. Nos 91–93 Farringdon Road, elevation by Henry E. Wood, architect, 1880. Demolished

These buildings are of six storeys above the basements and executed in buff brick with minimal dressings of stone or terracotta, and much of the detailing is carried out simply in brick: rusticated quoining and, on the warehouses, sunk panels dividing the double-height window openings of the intermediate floors. The foundry, of similar brickwork, was formerly surmounted by a segmental pediment with the name figgins, and the cast-iron railings in front have a motif based on the firm's monogram (Ill. 533).

Nos 77–79, built in 1882–3 by William Brass of Old Street for a Gainsborough engineering firm, Marshall, Sons & Co., is a fairly standard commercial block of that date, built of yellow brick and artificial stone dressings in a vaguely Italianate manner. The name of the architect is not known (Ill. 527). (fn. 139)

A slightly more unusual type, loosely Italianate again but with a hipped roof and dormers, was the warehouse at Nos 91–93, built in 1880 for John Gloag Murdoch, publisher, to designs by Henry E. Wood (Ill. 536). (fn. 140)

No. 103 was erected in 1865 as offices and living accommodation, with a large warehouse at the rear extending behind the sites—not built on until 1887—of Nos 99–101 and 105–107. It was designed by the architect John Butler for James and Richard Mason Wood & Co., typefounders, press manufacturers and suppliers of printing materials and equipment, whose existing premises were pulled down for the construction of the new Smithfield market. (fn. 141) The warehouse, latterly used as a garage, was demolished in the late 1980s for redevelopment and is now occupied by part of Herbal Hill Gardens. (fn. 142) The office building is mostly of stock brick, with twisty iron columns dividing the windows on the upper floors (Ill. 528).

House and shop building, 1870s

North of Farringdon Road Buildings, the east side of Farringdon Road (over the Metropolitan Railway's eastern tunnel) was built up with speculative houses and shops in 1872–6, erected on long leases from the railway company.

In 1872–3 George Day, a builder and contractor of Camden Town, erected the present Nos 88–106 Farringdon Road and No. 2 Exmouth Market, and five more shops on the opposite corner of Exmouth Street, these last being demolished for the construction of Rosebery Avenue about 1890. Fairly described at the time as 'handsome, substantial and commodious', (fn. 143) the buildings were designed for Day by the architect Rowland Plumbe, in a polychrome Venetian Gothic style. They are executed in Beart's gault brick and red brick, with Bath stone pilasters betwen the shops and foliated capitals of Doulton's terracotta (Ill. 537). (fn. 144) The Clerkenwell Tavern on the corner (No. 106, later incorporating No. 2 Exmouth Market and in recent years called the Penny Black) is of similar materials to the shops, but in a variant style. Opportunity was taken by the Vestry to improve the junction by further cutting back this corner, which had been rounded off as part of rebuilding in 1792 in order to keep clear of a New River Company water main. (fn. 145)

In addition to the main-road houses, Day built a few houses adjoining, in Vineyard Walk, and sheds and workshops on the ground at the rear. For several years Day himself seems to have been running both the new pub and a grocery next door at the present No. 104, as well as his construction business. (fn. 146)

No. 94 (the Quality Chop House) has been used as a restaurant since it was built, acquiring a measure of celebrity since the Second World War on account of its old-fashioned interior, the quaint slogans on the shopfront and, until recent years, the resolutely traditional workingclass fare. The principal decorations and fittings, restored in 1989–90 when the Chop House became an up-market restaurant, appear to be the result of a succession of improvements in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries, rather than the result of a single refitting of the premises. They include spartan benches of wood and castiron, an ornate frieze and a linenfold-panelled dado, and a ceiling of Steleonite stamped metal (Ill. 540). The chief item of interest, however, is the shopfront, fitted with panes of etched glass proclaiming 'London's noted cup of tea', 'Civility' and other attributes, together with the epithet 'Progressive Working Class Caterer' (Ill. 539). These were almost certainly added by William Robinson Putterill, an early proprietor, probably around the turn of the twentieth century; the facia is of more recent date. W. R. Putterill, or perhaps his father, took over the restaurant about 1880, and he continued there until about 1904, for much of which time he was an active member of Clerkenwell Vestry. He stood more than once for election to Finsbury Borough Council in the 1900s as a Progressive, and also served on the Holborn Union Board of Guardians, using with a fellow overseer the phrase 'Vote for the Workers' in their joint election publicity— referring specifically to their attendance record at meetings and trips to the Holborn workhouses to entertain the inmates, but also perhaps to their progressive politics. (fn. 147)

537. Nos 96–104 Farringdon Road in 2006, from the northwest. Rowland Plumbe, architect, 1872–3

538. Nos 116–152 Farringdon Road in 2006. Walter William Wheeler, builder, 1874–5

539. Quality Chop House, No. 94 Farringdon Road, in 1994

540. Quality Chop House interior, 1994, with Steleonite stamped metal ceiling

The remaining frontage as far north as the junction with King's Cross Road, purchased by the Metropolitan Railway from the Northampton Estate, (fn. 148) was built up almost entirely with houses and shops, the only large commercial building being a warehouse at No. 158 (now demolished). This was built for a waste-paper dealer, James Soanes, who also developed adjacent land in Attneave and Margery Streets. (fn. 149) Nos 114–152, a long, not entirely regular, terrace of bay-fronted houses, was erected in 1874–5 by a Notting Hill builder, Walter William Wheeler (Ill. 538). Wheeler was for a time in partnership with two other builders from Notting Hill, Arthur Mazzini Wheeler and William Warren, and all three took and developed other plots of clearance land near by, at Nos 164–170, further north, and in King's Cross Road and Lloyd Baker Street. (fn. 150) The houses north of Attneave Street, of which only a couple survive (Nos 160–162), were all flat-fronted.