Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Amwell Street and Myddelton Square area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp192-216 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Amwell Street and Myddelton Square area', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp192-216.

"Amwell Street and Myddelton Square area". Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp192-216.

In this section

CHAPTER VIII. Amwell Street and Myddelton Square Area

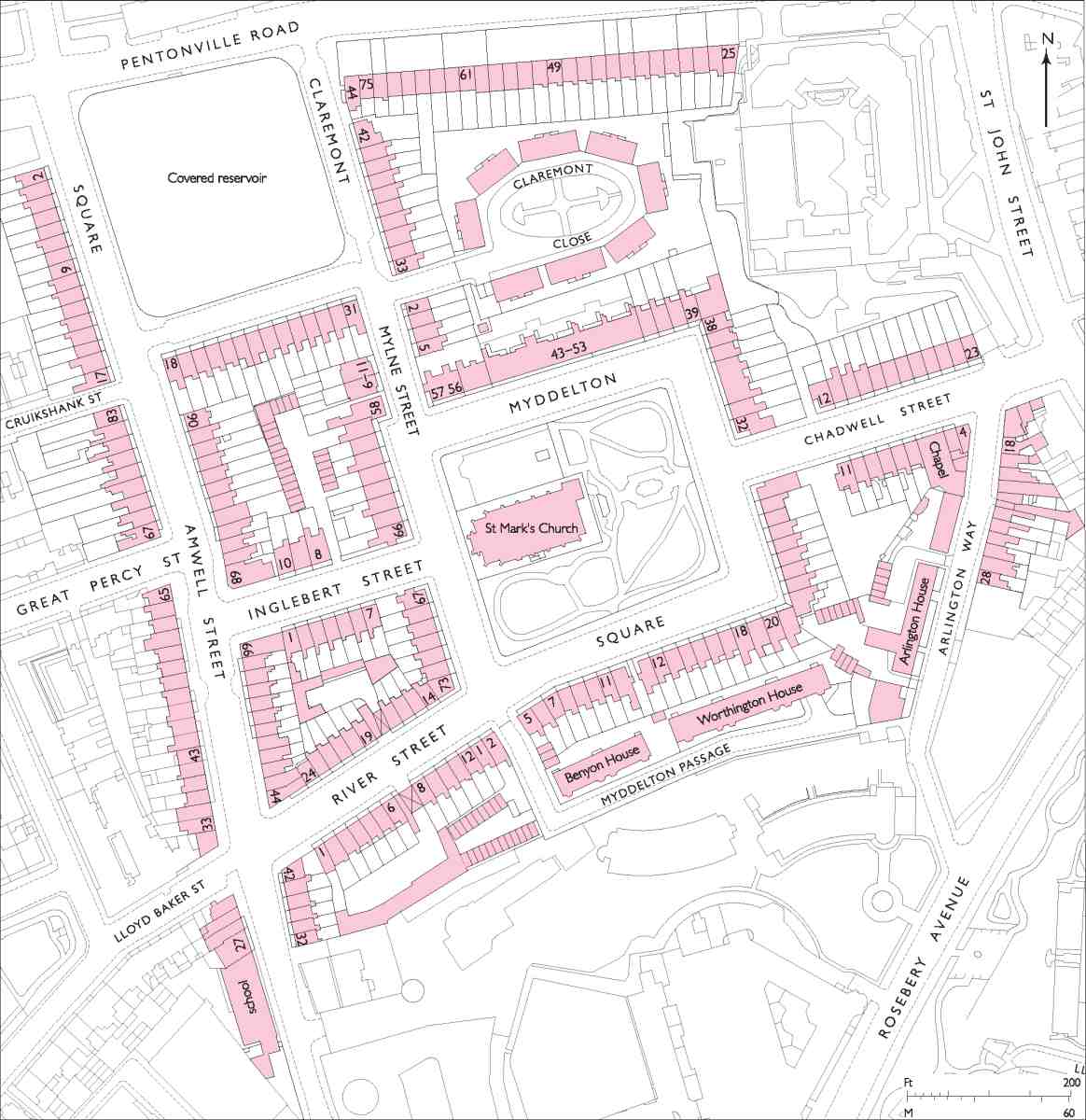

241. Amwell Street and Myddelton Square area in 2005

Almost the entire area around Amwell Street and Myddelton Square belonged historically to the New River Company, whose extensive Clerkenwell estate stretched from St John Street as far west as King's Cross Road. How this ground came to be acquired and built up with houses, and eventually disposed of, is related in the preceding chapter, which also discusses the planning and architectural character of the estate generally. The present chapter addresses in detail the individual streets, squares and buildings from Amwell Street eastwards. Bounded by Pentonville Road to the north, St John Street to the east and New River Head to the south (Ill. 241), this area derives unity from its concerted early nineteenth-century development with terraces and squares.

Following the chronology of development in the nineteenth century, the account starts in the north with Claremont Square, where the first houses on the New River estate were built, and the former Claremont Terrace in Pentonville Road. From there it moves to Amwell Street, a little-altered shopping thoroughfare of the 1820s, Myddelton Square, the best address, with the church of St Mark, and several short connecting streets. It concludes in the east and south with Arlington Way and Myddelton Passage, both extensively redeveloped in the twentieth century. Social and commercial characteristics, and notable residents, are briefly dealt with at the ends of the individual accounts of building and development.

Houses on the former New River estate fronting St John Street are described in volume xlvi of the Survey of London. The other parts of the estate are described in the present volume (see Ill. 238).

Claremont Square and Claremont Terrace

Claremont Square is a characteristically elegant early nineteenth-century square, stereotypical but for having only three built-up sides and, more remarkably, an aggressively prominent mound in place of a garden. This is built around a reservoir, originally open but now vaulted over, which antedates the houses by more than a century. When they were built, between 1815 and 1828, the north side was already long taken by the New Road between Marylebone and the Angel.

By this time the area north of the New Road was fully developed as the suburb of Pentonville, but still retained something of its old character of a semi-rural resort, with bowling greens and pleasure gardens. The ground by the reservoir, where a field path led towards fashionable Penton Street, was the obvious place to begin development of this northern part of the New River Company's land. Almost directly opposite, an independent chapel opened in the New Road in 1819, and it was from this that Claremont Square and the terrace immediately east took their names.

Upper Pond and Claremont Square Reservoir

The reservoir originated as the Upper or High Pond, dug in 1708 to provide a higher head of water than the Round Pond at New River Head, allowing New River water to be supplied to the West End. It was itself supplied by pump from New River Head. The pond was sited on the highest local ground, at the top of 'Islington Hill'. Almost square, with sides of about 200 ft, the one-acre pond was a substantial excavation for its time. It was part of a commercially important new departure for the New River Company, experimentally and expensively engineered by George Sorocold after years of discussion (see Chapter VI). To begin with, the pond was an open body of water with a sluice house on its south side; anglers availed themselves of its banks (Ills 208 on page 165, 239 on page 187). In 1757, following the formation of the New Road, it was enclosed by a 'high brick wall'. (fn. 1)

The reservoir was progressively embanked, to raise the water level. By the 1820s it was, Thomas Carlyle later recalled, 'all cased in tight masonry; on the spacious expanse of smooth flags surrounding which it was pleasant on fine mornings to take an early promenade'. (fn. 2) In 1826, soon after most of the square had been built, castiron railings with tasselled spearhead standards replaced the wall around the pond, the cost of the somewhat realigned enclosure being charged to the lessees of the houses (Ill. 242). Occupiers of the houses opposite in Pentonville Road refusing to contribute, the railings on the north side were taken down, sold and replaced with the brick wall that still stands. (fn. 3)

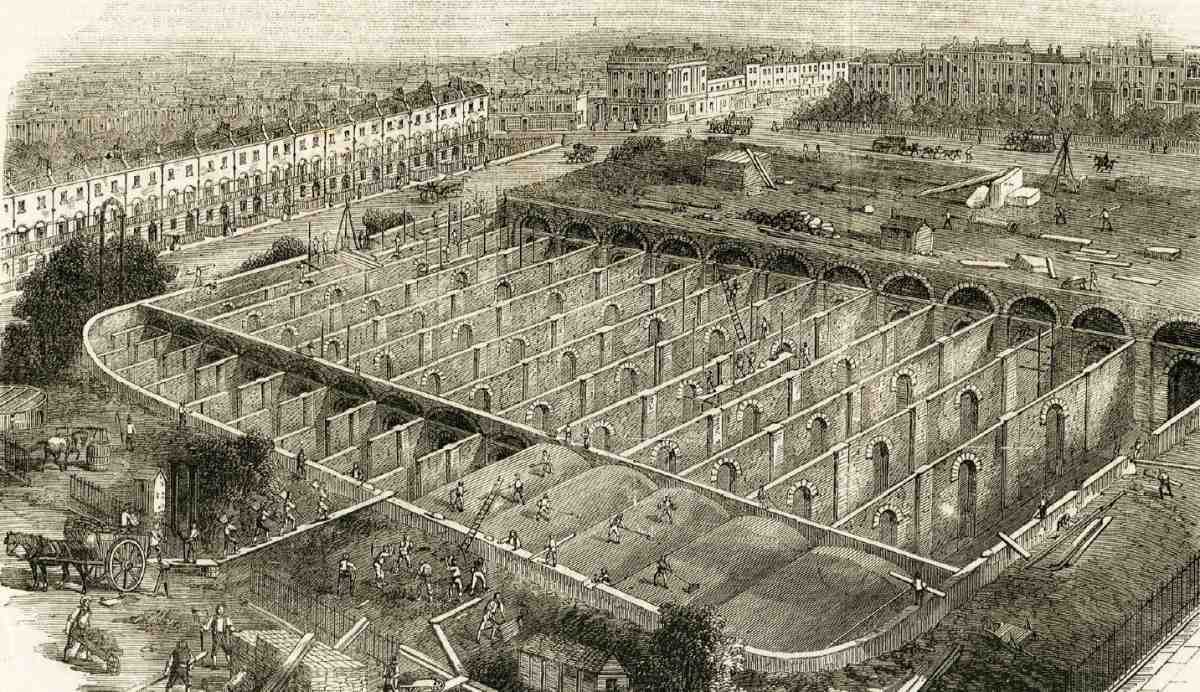

In 1854–5 the Upper Pond was reconstructed to comply with the requirement of the Metropolis Water Act (1852) that open reservoirs must be covered. Brick-lined, it is enclosed by massive walls up to eight feet thick, built within the sides of the old pond to allow a 21 ft depth of water over an area about 180 ft square, to hold about 3.5 million gallons. Across the floor a grid of arcaded walls rises to segmentally arched vaults, at a level high enough to permit the supply of water to Islington (Ills 243, 244). (fn. 4) The vaults were grassed over, and by the 1880s were home to 'a few melancholy sheep'. (fn. 5) At the north-west corner of the reservoir enclosure a public drinking-fountain, one of several in Clerkenwell supplied by the New River Company, was put up in 1862. (fn. 6)

242. Claremont Square, c. 1850, showing the south-west corner of reservoir with header pipe

243. Claremont Square Reservoir, reconstruction in 1855, looking north-west. W. C. Mylne, surveyor, 1854–5

244. Claremont Square Reservoir, interior in 2000

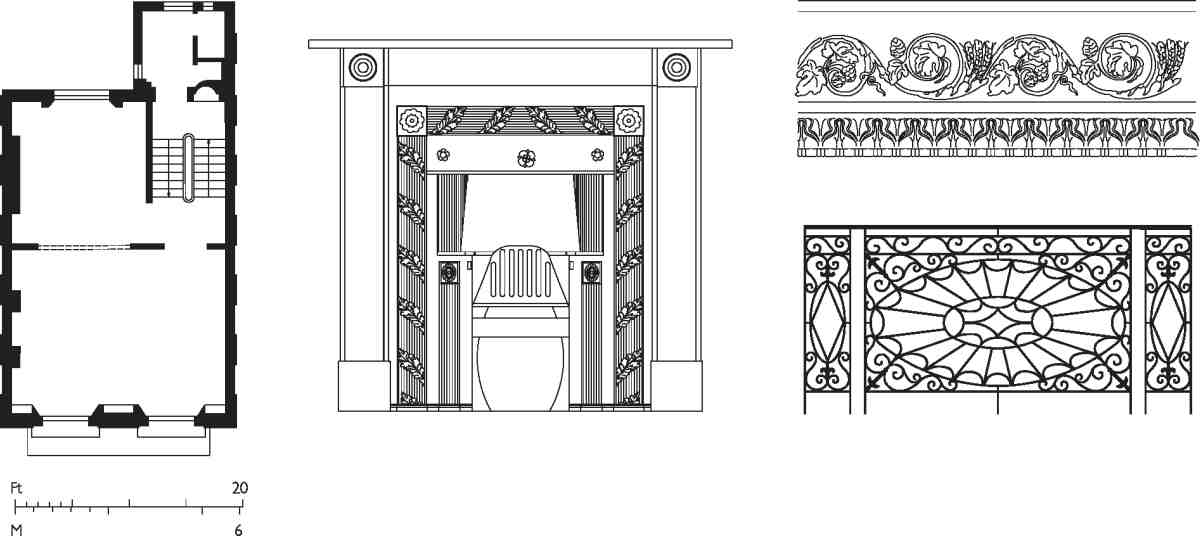

245. No. 16 Claremont Square. First-floor plan as existing, with details of cornice in first-floor front room, second-floor fireplace and balcony

The reservoir fell into disuse in the 1990s, but came back into service in 2003 to provide a kind of header tank or balancing reservoir for the London Ring Main, filling at night and emptying during the day. (fn. 7)

The houses in Claremont Square

246. Nos 2–17 Claremont Square (right to left) in 2005. Built as Myddelton Terrace

247. Nos 13–17 Claremont Square (right to left) in 2005. No. 16 built by and for John Scott, brickmaker, in 1821–3

The houses on the west side of Claremont Square were built in 1815–24 as Myddelton Terrace. This set the standard for the better houses of the New River estate, this being the first occurrence of the lower-storey rusticated stucco and first-floor blind arcading that was used hereabouts for the next twenty years. Behind 17 ft fronts the houses had two-room rear-staircase plans, with interconnecting front and back rooms. Beyond, there were long gardens. Thomas Carlyle observed in 1824 that the terrace was 'a new place; houses bright and smart, but inwardly bad as usual'. (fn. 8) There is no evidence that this row was initially projected as part of a square, but the presence of the reservoir would have made any other eventual outcome unlikely. The first twelve houses (Nos 1–11, with No. 1A at the north end, facing Pentonville Road) were built following agreements made in 1815, by Holborn and City speculators in the building trades who apparently worked in a consortium and bartered materials in lieu of payments (Ill. 246). Thomas Richard Read, a Gray's Inn Road glass merchant who had previously built on the Northampton estate in Clerkenwell, undertook the first seven houses (Nos 1A–6), and then assigned them all to others. Nos 1A and 1 (demolished 1922–3) were built in 1815–16 by Robert and George Cooke, glaziers and painters, of Fleet Street. Henry Hammond, a Holborn window-glass maker and dealer, already speculating elsewhere on the estate in Myddelton Street, took on Nos 2–5 and then, with a bricklayer, Thomas Abbot of Leather Lane, agreed directly with the New River Company to build five more houses (Nos 7–11), three of these being re-assigned to a stonemason, a painter-glazier and a plumber, all co-operating sufficiently as to avoid any straight joints in the front walls between Nos 3 and 12. (fn. 9) Charles Frederick Woolcott was 'running up' three of these houses in 1817, perhaps Nos 2–4, when Hammond, scarcely involved with the building work, fell bankrupt. There were links here to Thomas Woollcott, who had developed much of Woods Close (the area in and around Northampton Square) for the Northampton estate, in at least one instance with Read; and to George Woolcot, then a young surveyor, who later went into partnership with Bryan Browning, to whom Hammond owed £510. (fn. 10)

248. (top) Nos 18–31 Claremont Square (south side) in 1945

249. Nos 27–29 Claremont Square, reconstructed ground-floor plans

Myddelton Terrace was extended southwards in 1820–4, six more houses (Nos 12–17) being added so as to enable the formation of a square. Samuel Tustian, a Gray's Inn Lane plasterer who had built No. 6, was responsible for Nos 12 and 13. No. 14 was built by Henry Garling, an architect who had recently been appointed surveyor to the Rugby School estates. John Scott, the brickmaker who was later revealed as an embezzler, began to build No. 16 for his own occupation in 1821 by which time he had made more than three million bricks on the estate. His house is notably larger than the other houses, with a 20 ft front and four storeys, and strikingly fails to continue Mylne's elevational lines (Ills 245, 247). At the end of the terrace, No. 17 was occupied from 1830 by William Bond, who gave his name to Bond (now Cruikshank) Street. The entrance return to the house has been rebuilt. (fn. 11)

The square was only properly formed in 1822–5, being briefly known as River Square before the name Claremont was adopted in 1825. In 1822 negotiations for the development of the east and south sides by Thomas Oliver, a Goswell Road builder, fell through. Then in 1823 another builder, William Oliver of Duncan Terrace, City Road, who was then completing Claremont Terrace, undertook to build seven houses adjoining (Nos 38–44). Richard Chapman, an Islington builder, agreed to build the rest: six on the east side (Nos 32–37) and the whole south side (Nos 18–31), all as second-rate houses with 18 ft fronts. The whole east side was complete by 1825, except for No. 32 (demolished c. 1934). The fourteen-house terrace on the south side, which Chapman built himself, followed in 1826–8 (Ills 242, 248, 249). This was one of the largest single developments on the New River estate, and the only terrace in the area to make a nod towards a 'palacefront' conception. Symmetry is spoiled only by the position of the entrance to No. 24. Internally, front and back rooms interconnected, as was typical on the estate, with, unusually, curved corners at the backs of the front rooms. (fn. 12)

Outwardly the houses on both the east and south sides closely followed the Myddelton Terrace precedent, giving Claremont Square considerable visual consistency. As everywhere on the estate there are variations of detail, in doors and door surrounds, fanlights and first-floor castiron balconies. While the stucco impost bands to the west are plain, those to the south and east are reeded or corniced. There are mansards on the east and west sides, but not on the south, where there is a full fourth or attic storey with a stucco parapet (now interrupted by rebuildings), a difference calculated to maintain consistent height, compensating for the fall of the ground to the south. At the north-east corner Nos 42 and 44 are double-fronted (Ills 250, 251). No. 44 was built as part of Claremont Terrace, and for that reason has four full storeys. Its part-flat roof, railed round with Gothic cast iron, offers views down Pentonville Road to St Pancras.

250. No. 42 Claremont Square in 1983. Built and later occupied by William Oliver

The following list summarizes the development of the square. (fn. 13)

West side (originally Myddelton Terrace)

Nos 1 and 1A. Robert and George Cooke, builders, 1815–16. Demolished

Nos 2–5. Henry Hammond, builder, completed by others, 1815–21

No. 6. Samuel Tustian, builder, 1815–18

No. 7. George Burnell, builder, 1815–17

No. 8. Thomas Lovell, builder, 1815–17

No. 9. William Boyer, builder, 1815–17

Nos 10–11. Henry Hammond, builder, 1815–17

Nos 12–13. Samuel Tustian, builder, 1820–4

No. 14. Henry Garling, builder, 1822–3

No. 15. Richard Gifford, first lessee, 1821–3

No. 16. John Scott, builder and first occupant, 1821–3

No. 17. William Barlow, builder, 1823–4

South side

Nos 18–31. Richard Chapman, builder, 1826–8

East side

No. 32. Richard Chapman, builder, 1828–9. Demolished

Nos 33–34. Ralph Brown, builder, 1825

Nos 35–37. Ralph Brown, builder, 1824

Nos 38–42. William Oliver, builder, 1823.

Nos 43–44. William Lenton, builder, 1824.

Nos 25–75 Pentonville Road

This long row of 26 houses, immediately east of Claremont Square, was built in 1818–24 as Claremont Terrace. Built from east to west, the houses continue the set-back building line (required by the New Road Act) of Angel Terrace, the shorter row of 1818–20 that stood where the Angel Centre now is (page 366). A dozen or more builders were involved in the development, some only as speculators. Unity was ensured by the New River Company's surveyor W. C. Mylne, the house type following that established in Myddelton Terrace in 1815.

The earliest substantial agreement in 1818 was with Thomas Richard Read, who undertook to build six thirdrate houses (Nos 25–35), keeping the westernmost for himself and re-assigning the others. Nos 31 and 33 went to employees of the New River Company: James Treacher, Assistant Street Inspector, and Richard Saywell, Collector. Saywell also built Nos 39 and 41 and a house of c. 1819 in Myddelton Place opposite Sadler's Wells, where he lived. Thomas Woollcott had agreed to build Nos 41–47 in October 1818, but he was dead by June 1819 when the agreement was transferred to James Hall, a Charterhouse Square plumber. In 1819 and 1820 Thomas Elliott took on Nos 49–57, and in 1822 William Oliver agreed to build the seven houses (Nos 63–75) at the west end of the terrace. Oliver took No. 65 to live in himself (by 1840 he had moved to No. 42 Claremont Square), and assigned five of the rest to William Lenton, bricklayer. (fn. 14)

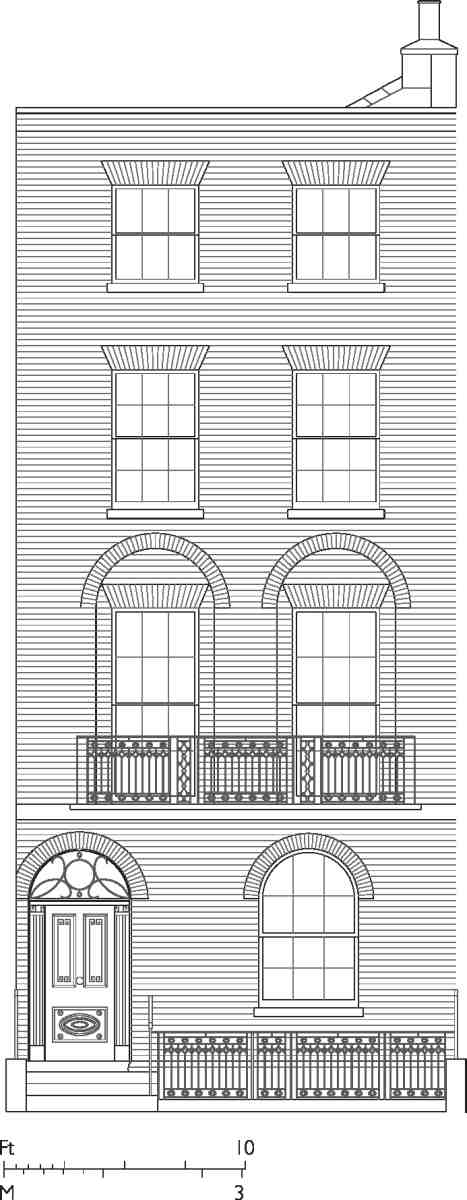

The houses all have four full storeys with basements (Ills 251, 252), 18 ft fronts and two-room rear-staircase plans. Most were built with water-closet wings from the start. As well as deep front gardens separating them from what has always been a busy road, there were originally long back gardens, of which there is a sole survivor at No. 67. Behind these gardens there was associated stabling in Claremont Mews, since redeveloped as Claremont Close. Broad uniformity is compromised, or enlivened, by considerable variation of detail. Nos 25–47 all have stucco ground floors, while houses further west do not. With the exception of Nos 67–75 there are no impost bands, as there were at Myddelton Terrace and on most local developments of the 1820s. There is much Gothick-patterned cast iron, on balconies and area and doorstep railings. Some variations in the features can be identified with particular builders, such as the medallionteardrop fanlight that recurs at Nos 33, 39 and 41, the houses built by Saywell. All the houses built under William Oliver have anthemion balconies, and Thomas Elliott's are distinctive for the Greek-Revival detailing at their entrances.

251. Claremont Terrace (Nos 25–75 Pentonville Road), west end in 2005, looking south with No. 44 Claremont Square to right. W. C. Mylne, surveyor, 1819–24

Builders of the individual houses are as follows: (fn. 15)

Nos 25–29. Robert Foot, 1819–20

No. 31. James Treacher, 1819–20

No. 33. Richard Saywell, 1819–20

No. 35. Thomas Richard Read (also first occupant), 1818–19

No. 37. Charles Douglas, 1818–19

No. 39. Richard Saywell, 1818–20

No. 41. Richard Saywell, 1819–20

Nos 43, 45. James Hall, 1819–20

No. 47. Nicholas Mawbey Johnson, 1819–20

Nos 49, 51. Thomas Elliott, 1819

No. 53. Thomas Elliott, 1820–1

No. 55. Jonathan Barrett, 1820–1

No. 57. Richard Barrett, 1820–1

No. 59. Edward Higgs, 1822

No. 61. Thomas Oliver, 1822–3

Nos 63, 65. William Oliver and William Lawrence, 1822–3

Nos 67–71. William Lenton, 1822–3

Nos 73, 75. William Lenton, 1822–4

Social character and adaptations

Once it was essentially complete in 1827 Claremont Square was deemed 'the greatest improvement the parish has received for many years', (fn. 16) and it began with respectable middle-class occupancy, merchants and clergymen to the fore, as did Claremont Terrace, where Antonio Da Costa, a Brazilian consul, inhabited No. 57. The actress and music-hall singer Miss FitzHenry (real name Emily Soldene) was born in Claremont Square about 1838, the daughter of a lawyer. (fn. 17) In its early years Myddelton Terrace had two particularly notable residents. The first of these was George Cruikshank, the satirical illustrator and radical, who had been a successful caricaturist since 1811. His earnings in 1820 included £100 from King George IV who, unavailingly, asked him thereby 'not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation'. So enriched, Cruikshank had moved by early 1821, with his widowed mother and younger sister, to what is now No. 11 Claremont Square. In 1824 the family moved a short distance along the street to a new house, now No. 69 Amwell Street. Edward Irving, founder of the Catholic Apostolic church, who achieved fame as a preacher immediately upon coming to London from Scotland in 1822, lived at No. 4 for a few years from 1824. The year before he had published his first book, married, and begun planning a National Scotch Church in London. His close friend Thomas Carlyle stayed with him for a few weeks in 1824. (fn. 18)

Already in 1851 Nos 15, 30 and 31 Claremont Square were lodging and boarding houses, and other houses were sub-divided later in the century, when there were growing numbers of tradespeople in Claremont Terrace. Walter Sickert lodged briefly in Claremont Square in 1880–1 when a young actor, hosting a 'hilarious tea party at his book-strewn rooms' (fn. 19) for a bevy of young women that included Ellen Cobden, his first wife, whom he was then courting. Also resident in the square at this time (at No. 21) was the former Chartist, Robert Kemp Philp, compiler of Enquire Within Upon Everything, who lived in lodgings at No. 20 until his death in 1882. (fn. 20)

252. No. 49 Pentonville Road, reconstructed front elevation

In the 1890s the square was 'a noted residence of medical students' and John Scott's house at No. 16 had become the home of the vicar of St James's Clerkenwell, the Rev. John H. Rose; a later resident of this house was Edward Delfosse, whose light-engineering works were nearby, off Holford Square (see page 228). (fn. 21)

The New River Company oversaw many flat-conversions, from as early as 1935–6 at No. 10. A systematic conversion programme was carried out in the late 1970s and into the early 1980s, following the acquisition of the estate by the Borough of Islington. This was carried out under the borough architect Alf Head by Andrews Sherlock & Partners, architects of the borough's low-rise, highdensity Popham Street Estate (1968–74). At Claremont Square individual houses were made into two maisonettes (reducing density), the lower ones having their entrances at basement level and the upper ones having roof terraces. A number of houses had to be substantially rebuilt, No. 31 in its entirety. Claremont Terrace has also seen much subdivision, including the lateral conversion of Nos 29 and 31. Following right-to-buy legislation some homes were sold, and a few divided houses have lately been taken back into single or double occupation. (fn. 22)

Amwell Street

Situated on the slope of a hill, Amwell Street rises from the south to open out as a broad and picturesque shopping street, its upper stretches lined with regular stock-brick terraces of the early 1820s. These have integrity and dignity, as well as a lively aspect, with blind arcading rolling along up to Claremont Square (Ill. 253). The coherence of the essentially unaltered early nineteenth-century streetscape conceals a subtle and engaging variety of detail. Occupancy here has always been mixed commercial and residential, and groups of shops in houses, once unremarkable, have come to seem a precious survival. The lower and narrower part of the street, south of the parochial school, was known as Upper Rosoman Street from 1820 until 1936. Its much more disparate buildings are more appropriately discussed elsewhere (see Chapters III, IV and X).

Long before it was built up, the route of Amwell Street was a path, running from just west of New River Head towards Islington along the sides of fields known as the Great and Little Butcher's Mantles (Ills 208, 239). Somewhat diverted by the Upper Pond the path was rerouted to run straight along its west side, past a raised site where the Civil War Fort Royal had stood (page 2), and up, after 1756, to the New (now Pentonville) Road. Part of the field-edge path ran along a property boundary, Robin Hood's Field to the west being part of the Lloyd (later Lloyd Baker) estate. (fn. 23)

Building Development

The street's development in the early 1820s fell within the much bigger speculative building projects undertaken by the New River and Lloyd Baker estates. The two campaigns dovetailed effectively, to the extent that the street is not readily recognizable as the product of two centres of control. This was due to joint planning, put into effect by 1819 when W. C. Mylne, for the New River Company, and John Booth, for Lloyd Baker, had several meetings and shared their building plans. The company had been intending to build a new street along this route for several years, but it was not until March 1820 that it was formally agreed that this would be laid out along the existing path and on the company's land. In return for access to the street Lloyd Baker agreed to front it in Mylne's 'house style', very different from the architecture of his own estate.

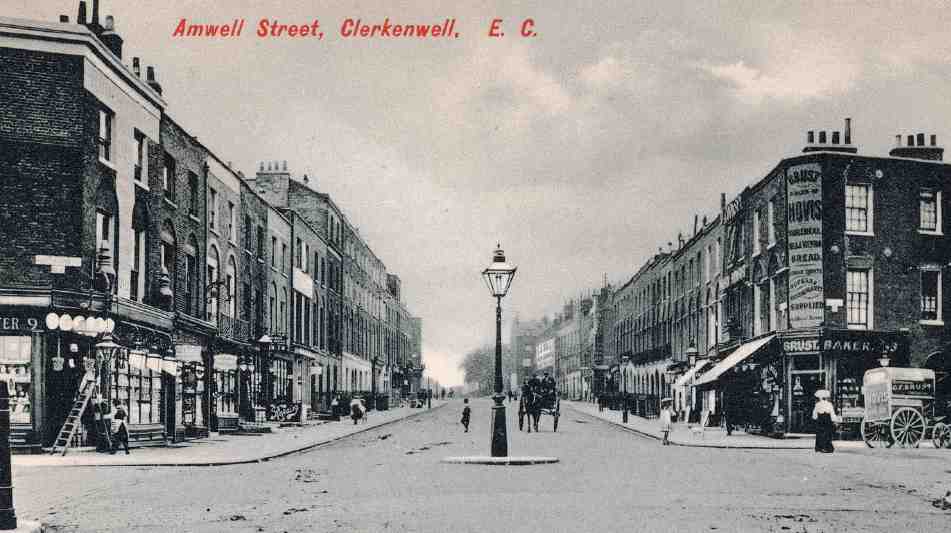

253. Amwell Street looking north in 1906. From junction with Lloyd Baker Street (left) and River Street

The Lloyd Baker estate was first off the mark, William Wade agreeing to develop its western frontage in 1820. The New River Company's first building agreements, also on the west side, were not made until early 1822. Progress thereafter was rapid, and both sides were mostly built up by 1825. Initially the street was known as Union Street, but in 1826, when development was virtually complete, it was redesignated Amwell Street, after one of the Hertfordshire sources of the New River. (fn. 24)

Nos 27–65 Amwell Street consist of twenty-two houses, comprising a longish terrace to the north of Lloyd Baker Street and a short one to the south, built about 1820–5. Except for No. 27 they were all on land belonging to William Lloyd Baker. They were originally called Thompson's Terrace, for reasons unknown; the name can still be seen on a tablet dated 1824, set into the brickwork between Nos 47 and 49. (fn. 25) A conspicuous feature of the two blocks was the large number of shops. Nos 37–41 and 63–65 are known always to have included shops, and others may have done too.

In return for access to the company's new roads here and in Great Percy Street, Lloyd Baker's surveyor, John Booth, had agreed with Mylne back in 1818, when Amwell Street had hardly advanced, that the fronts of the houses here should 'correspond with ones already built by the New River Company'. (fn. 26) But the builders of Thompson's Terrace were not required to follow Mylne's elevations exactly. Though the characteristic New River roundheaded relieving arches over the first-floor windows are present, the equally typical stone impost bands are lacking. Most of the houses in the two terraces were originally three storeys high, but the six at Nos 45–55, slightly off-centre, had four.

Thompson's Terrace was first undertaken by a single carpenter-builder, William Wade of Gloucester Street, Queen Square. In 1820 he contracted to erect eighteen houses to the north and two to the south of Lloyd Baker (then just Lloyd) Street, but he completed only six before succumbing to bankruptcy in 1823. Now numbered 29–35 Amwell Street and 24–25 Lloyd Baker Street, the majority were leased to John Summers, a neighbour of Wade's in Gloucester Street. (fn. 27)

254. Nos 57–65 Amwell Street (left to right) seen from Great Percy Street in 2007

Separately, on a site belonging to the New River Company and used for storing water pipes, Wade also built the house at the southern end of the terrace, now No. 27, which he occupied himself for many years. Though wider than his other houses with a central front door, it has the elevational treatment stipulated by the company, here looking a little stretched. (fn. 28)

After Wade's bankruptcy Robert Rawlings of Red Lion Square, gentleman, contracted in 1824 with Lloyd Baker to build the remaining houses along Amwell Street and to develop the return frontage in Great Percy Street and the east side of Lloyd Street. (fn. 29) Four of the plots in Amwell Street he subcontracted to his 'managing man', Benjamin Bellamy, a carpenter and coal dealer in Spa Fields, who in turn subcontracted them to John Ramsay, a tailor-turnedbuilder from Lambeth. Ramsay built Nos 37–43, completing them in 1825. The remaining houses (apart from No. 65) were nominally erected by Rawlings (Ill. 254). The builder could have been Bellamy, at least until his bankruptcy in September 1826, but a Hoxton builder, Benjamin Matthewson, was also involved with Rawlings. (fn. 30) All these houses were occupied by 1829, except for Nos 53 and 55 which remained empty until the 1830s. (fn. 31)

No. 65 was excluded from Rawlings's contract because Wade had earlier agreed to sublet this corner site for a public house. In the event it was leased in 1825 to a perfumer, James Wakefield of Lamb's Conduit Street, also Rawlings's nominee for the adjoining No. 63. (fn. 32)

Back on the New River land, Nos 67–83 were built in 1822–4 as an extension of Myddelton Terrace, in which they were numbered until 1877. They broadly follow the earlier houses in elevation and plan, but have slightly wider frontages of 18–20 ft and lack attics. Original details vary, and alterations have brought further variation. The main building agreement, made in July 1822, was with William Oliver, who took on the seven houses at Nos 67–79. The plots of Nos 67–73 were passed on to George Paul, a builder of Great Saffron Hill, whose houses were given stuccoed ground-floor fronts with round-headed windows, unlike the others. The corner house at No. 67, substantially rebuilt in 1894 and perhaps further rebuilt since, has always had a shop. At the other end, No. 83 was raised a storey in 1855, and its balconies were probably replaced at the same time. (fn. 33)

The whole east side of Amwell Street was undertaken as a single speculation. In December 1822 Edward Cowper Fyffe, a New Cavendish Street grocer, took out an agreement to build 30 third-rate houses on the lines of those already going up opposite, to include shops as he saw fit. (Fyffe also took on more property behind, in Inglebert Street, Myddelton Square and River Street). The northernmost section (Nos 68–90, originally Pentonville Terrace) and some of the shop-houses further south (Nos 40, 42 and 66) were erected during 1823–5 by several builders acting as Fyffe's assignees. These included Thomas Oliver, who built Nos 66, 76, 78, 88 and 90. The taller house at No. 76, which has a view down Great Percy Street, was for Oliver himself. It originally had a large Lshaped garden or yard with a frontage to what has become Inglebert Street. Still there in 1849, Oliver then styled himself a 'land surveyor'. (fn. 34) After Fyffe's bankruptcy late in 1824 his agreement was assigned to Edward Garland and Philip William Perkins, builders, then of White Conduit Street in Pentonville. Within two years they had built Nos 44–64, except Nos 58 and 60 which were put up by William Goodwin. Garland, who had earlier built No. 80 under Fyffe, was himself living over a shop at No. 48. The four most southerly houses at Nos 32–38 were built by Thomas Marsh in 1825–8. (fn. 35)

Amwell Street's houses are of Mylne's standard New River estate type, generally with 16–17 ft fronts and of three storeys, without attics (Ill. 255). Some ground-floor fronts are stuccoed, others not, and nearly all have roundheaded windows. There is much variety in doorcases, fanlights and balconies, and the ramping up of impost bands is an enlivening detail.

Social and commercial character

Amwell Street has always attracted inhabitants from across a fairly wide if predominantly middle-class spectrum, with professionals, artists and craftspeople, particularly jewellers, alongside shopkeepers and other tradespeople. From early on there were lodging-houses, and in later times some houses were more formally divided into flats and bedsits.

George Cruikshank, already encountered at No. 11 Claremont Square (Myddelton Terrace), moved downhill in 1824 to become the first occupant of what is now No. 69 Amwell Street. In 1834 he moved to No. 71 next door, where he stayed until 1849, when a breakdown brought about by financial troubles and the death of his wife caused him to move away. (fn. 36) George Childs, another artist and, like Cruikshank, a friend of the radical publisher William Hone, lived at No. 49 in the 1840s and 50s, and Samuel Lacey, the book engraver, lived at No. 82 from when it was new into the 1850s; these people worked from houses that were not in any way specially adapted for their trades. From the 1850s to the 1880s No. 60 was successively occupied by Rowland Nash, a lawyer of some eminence; Thomas Cooper, a watchmaker; Charles Hunt, an aquatint engraver; and Alfred Gilliam, a jeweller. (fn. 37)

255. Nos 56–64 Amwell Street (right to left) in 2005

Many other houses were built with shops. Next door to Cruikshank, at No. 67, the first tenant in 1824 was a baker, Jonathan Everard, who stayed for more than twenty years. On the east side of the street there were originally twelve shops, all near the side streets, at Nos 40–52 and Nos 66–72. This continues to be the case, except at No. 40, which was built in 1823 by John Youens, a Holborn bootand-shoe maker. The large corner house at No. 42 (Ills 256–8), built the same year by John Summers, was first occupied by M. Lawrence & Co., 'oil and Italian warehousemen', that is vendors of olive oil and other imported groceries, a use that was perhaps introduced by E. C. Fyffe, the West End grocer, to raise the tone of the whole speculation. It was sustained by other occupants into the 1850s. Around 1860 the shop was taken by Henry Stanton, an auctioneer, who built a saleroom in the garden (since demolished) and in 1865–6 remade the shopfront, adding the present Doric portico. Auctioneers continued here until 1914 when the mansard attic was rebuilt and Lloyd Lloyd took the property, adapting it by 1921 to be a dairy, with the shopfront re-fenestrated. (fn. 38) Lloyd (known locally as 'Lloyd Squared') and his descendants continued through the rest of the twentieth century; their shop was described in 1972 as 'one of the finest existing dairies, worth anyone's pilgrimage'. (fn. 39) Following several years of disuse it re-opened briefly as a grocery in 2005–6, with the shopfront and much of the early twentieth-century interior still intact.

No. 44, on the facing corner, was a baker's shop from at least 1830 until the 1970s (Ill. 253); the ovens that remained thereafter included one installed in 1889 by Charles Frederick Brust, who had the bakery for about thirty years either side of 1900. There was even longer continuity at No. 46 where Daniel Cooksey & Son, funeral furnishers and undertakers, remained from the late 1830s until the 1980s. (Looking back over thirty years' trade in the 1890s, Cooksey noted 'There used to be what they called a "plum season" in the autumn, but improved drainage has completely put an end to this'.) (fn. 40) The shopfronts at Nos 48–52 originally had bow-window fronts, and Nos 50 and 52 still have them, though remade. No. 66 was first occupied by Thomas Phillips, linen draper, and by 1845 had become another Italian warehouse. Its corner shopfront, remade in 1851, retains a bowed fascia and outer pilasters. The shop, which continues as an off-licence, belonged to Edmund Davies, a wine merchant, in the early twentieth century when stabling and other accommodation was added along Inglebert Street.

256. No. 42 Amwell Street in about 1830 (then numbered No. 54)

257. No. 42 Amwell Street in 2007

258. No. 42 Amwell Street, as Lloyd's Dairy; interior in 1994

On the Lloyd Baker sector of the street, by 1841 No. 63 was occupied by a butcher, who used the yard at the back for slaughtering. Other occupants at that time included two chemists, two drapers and a grocer. (fn. 41) No. 35 was a chemist's shop from 1843 until quite recently and has retained its Edwardian fittings. The present shops at Nos 24 and 31 date from 1847, when Frederick Barlow, a surveyor, designed the shop fronts and a new entrance for No. 24, in a single-storey projection against the flank wall. (fn. 42)

On the opposite corner, No. 68 has always been a public house. Until the 1990s it was called the Fountain, no doubt in allusion to the spring at Amwell. Since then it has been Filthy MacNasty's Whiskey Cafe, which became wellknown as a haunt of bohemian musicians and literati, among them the singer Shane MacGowan and Allen Ginsberg. The present neo-Georgian building, broadly but not carefully in keeping with the street, with red-brick dressings and a ground-floor front of glazed tiles, dates from 1932–3. The architects were F. J. Eedle & Meyers. (fn. 43)

Clerkenwell Parochial Church of England Primary School

The school was built in 1828–9 to replace the 70-year-old schoolhouse at the corner of Aylesbury Street and Jerusalem Passage, where the lease expired in 1830. Negotiations for building ground on the New River Company's estate were opened in 1825 by the governors (led by the embezzler John Scott) and a lease was ultimately secured at nominal rent. This was for a former iron-pipe yard, opposite the company's works yard, which had became redundant with the completion of the wooden-pipe replacement programme (see page 188).

The school, designed by the architect John Blyth with input from W. C. Mylne for the New River Company, opened in 1830 having cost about £3,500. About half came from voluntary contributions, and £500 from the National School Society, whose system the parish had adopted in 1816. Long and low, it is built of whitish brick in a gaunt Tudor style (Ill. 259), with separate entrance bays for boys and girls to the north and south respectively. The adjoin ing schoolmaster's house is somewhat set back, with a great fig tree alongside.

259. Clerkenwell Parochial Church of England Primary School in 1943, John Blyth and W. C. Mylne, architects, 1828–9

There were originally two large schoolrooms— boys below and girls above. The boys' was the larger, measuring 90 ft by 40 ft, divided by two rows of seven cast-iron columns. Though an Anglican foundation, the scale of the rectangular rooms and the suggested capacity of 1,000 were in keeping with the principles promulgated by the Nonconformist educationalist Joseph Lancaster, whereby 'unclassified' children sat all together in rows in their hundreds, with an allowance of seven square feet per child.

In 1830, 338 boys and 210 girls were enrolled. By the 1890s the school was deemed full with 900 children, numbers declining thereafter to below 600 in the 1930s, and to 208 in 2000. The schoolrooms were subdivided in 1906–7, and further alterations were made in 1952–4 when the lettering on the parapet was lost. (fn. 44)

Myddelton Square

Myddelton Square is the largest square in Clerkenwell. Its amplitude and its plain stylistic cohesiveness provide a stately precinct for a substantial church, forming the principal set piece of the New River estate's developments of the 1820s. Some post-war and other rebuilding has not significantly compromised these qualities, but, as is usual in the area, the impression of uniformity proves on closer examination to be deceptive. Centrally approached from the east, where there are re-entrant corners, the square is more irregular on the west side, with a kink in the building line to the southwest. There is what Ian Nairn called a 'cheerful stumble uphill' on the east and west sides, and considerable variety in the elevational details of the square's 75 houses, erected over twenty-one years by thirteen different builders.

By 1818 the New River Company had in mind a square with a church, and three years later W. C. Mylne was preparing plans for a generously laid out square on what had been the Butcher's Mantles. The first building agreement and the go-ahead for the church came in 1822, but it was not until 1823 that development commenced in earnest, and the name of the square was resolved. Initially it had sometimes been called Chadwell Square, but it was the name of the New River Company's founder that stuck. By January 1824 agreements had been reached with ten builders for the development of all four sides, each side essentially being divided into three unequal parcels, of from three to nine house plots. Building was not completed until 1836.

First to start was David Barkley, a St John Street butcher, who took on Nos 3–7 on the south side in 1822. The break in the building line between Nos 7 and 8 suggests that work may have begun before the final lines of the square had been set out. In early 1823 Edward Cowper Fyffe, already engaged on Amwell Street, agreed to build Nos 65–73 on the west side and Richard Chapman undertook Nos 51–57 on the north side at the same time as he committed to the south side of Claremont Square. Following his bankruptcy Fyffe's agreement transferred to Garland and Perkins in 1825 (see Amwell, Inglebert and River streets). Later in 1823 William Oliver agreed to build four houses at the east end of the south side (Nos 18–21). Thomas Priddle of Cross Street, Islington, and William Manser of Wardour Street, both carpenters, arrived on the scene as partners and agreed to build eighteen houses (Nos 9–17 and 22–30) to complete the south side and begin the east. James Armsby, a City Road builder, James Mansfield and Thomas Oliver each took three-house plots, on the north, east and west sides, respectively, Oliver working with William Smith of Arlington Street (Arlington Way), who called himself a surveyor. Samuel James Buckingham took the last plots on the north side, and Chapman added the north end of the west side to his commitment. Finally, William Harris, a Holborn optician and speculator, agreed to build Nos 1 and 2 (part of a bigger parcel with Nos 8–12 River Street), and 34–38.

260. Myddelton Square, west side in 1939

261. Myddelton Square, north side in 1906

262. Myddelton Square, south side in 2005

By 1826 there were nineteen houses on the south side, of which seventeen were occupied, and by 1828 this side was complete; 62 of the 73 houses then intended were listed in the ratebooks, implying that so many plots were at least staked out, only Chapman's ground at Nos 51–61 being omitted. In 1829 the square was enclosed with railings and laid out with ornamental gardens. This work, paid for by the lessees, was by Mansfield and Durant Hidson. The gardens were for use by the inhabitants only, the church being separately railed. Despite these advances progress had slowed down significantly in the late 1820s when the building boom had bust. Only 48 houses were complete and occupied in 1830. The New River Company grew impatient, and there was much chivvying of builders to complete the square in 1829–31. Armsby, now living in the square and working with Thomas Sowter, alternatively identified as another builder of City Road, or as a pianoforte maker of Lloyd Square, had taken over Buckingham's unfulfilled agreement for Nos 39–46 in 1827. He was threatened with Chancery in late 1831 to get him to build his last house at No. 39. Mansfield only finished his east-side corner at Nos 31–33 in 1833, and in 1834 Chapman's second agreement had to be transferred, along with plots on the west side of Mylne Street, to James Fisher, another City Road builder, who had already built Nos 65 and 66 under Garland and Perkins in the late 1820s. Fisher completed the last four houses at Nos 58–61 in early 1836.

A broad gap had been left between Nos 11 and 12 for a road to Sadler's Wells. This was never formed and so Nos 11a and 12a were inserted in 1842–3, leaving just a narrow path along which the northern arm of Myddelton Passage ran until 1950. These two houses were built by Richard Saywell, the New River Company employee who had been speculating on the estate since 1818. (fn. 45)

Builders of the individual houses in the square are listed below. (fn. 46)

South side

Nos 1–2. John Ramsay, 1826–8

Nos 3–7. David Barkley, 1822–3 (Nos 3 and 4 demolished)

No. 8. David Barkley, 1823–4

Nos 9–11. Thomas Priddle and William Manser, 1823–4

Nos 11a, 12a. Richard Saywell, 1842–3

Nos 12–14. Priddle and Manser, 1823–4

Nos 15–17. Priddle and Manser, 1825–6

Nos 18–21. William Oliver and William Lawrence, 1823–4

East side

Nos 22–24. Priddle and Manser, 1829

Nos 25–26. Priddle and Manser, 1829–30

No. 27. Priddle and Manser, 1829–32

Nos 28–29. Priddle and Manser, 1829–30

No. 30. Priddle and Manser, 1827–30

Nos 31–33. James Mansfield, 1829–33

Nos 34–38. William Harris, 1827–31

North side

No. 39. James Armsby and Thomas Sowter, 1831–2

Nos 40–42. Armsby and Sowter, 1827–9

Nos 43–46. Armsby and Sowter, 1829*

Nos 47–49. Armsby, 1824–5*

No. 50. John Bringloe, 1824–5*

Nos 51–53. Richard Chapman, 1829–30*

No. 54. Chapman, 1829–30

Nos 55–57. Chapman, 1830

West side

Nos 58–59. James Fisher, 1834–6

Nos 60–61. James Fisher, 1834–5

Nos 62–64. Thomas Oliver and William Smith, 1823–6

No. 65. James Fisher and William Smith, 1825–9

No. 66. James Fisher and George Bishop, 1825–9

Nos 67–73. Garland and Perkins, 1825–7

*Rebuilt 1947–8 by New River Company, following war damage

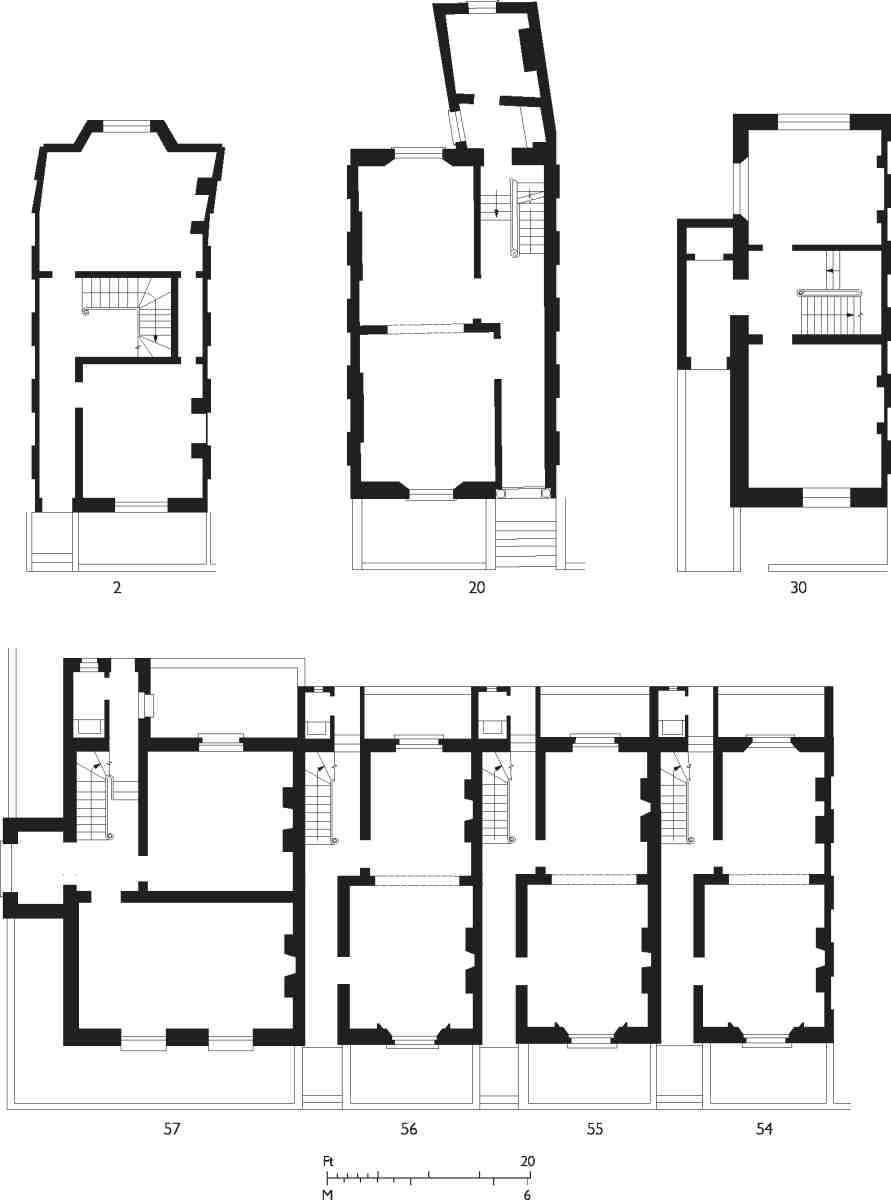

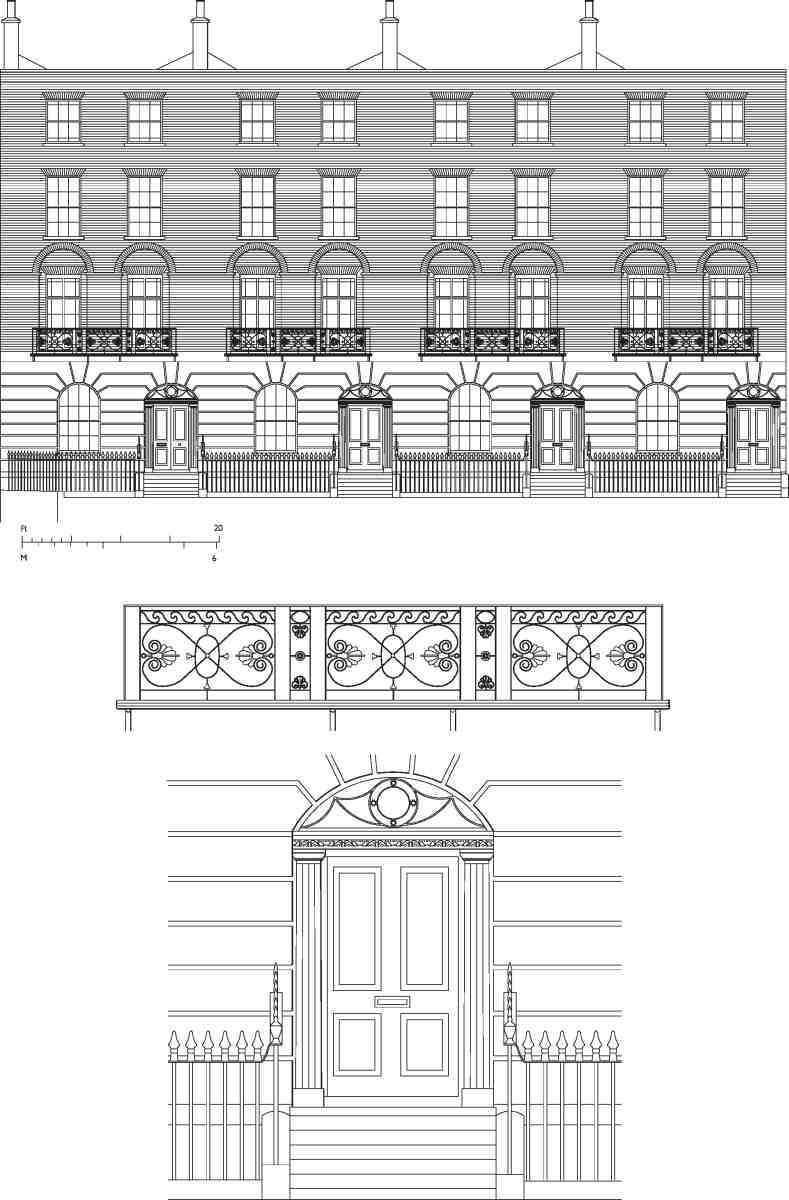

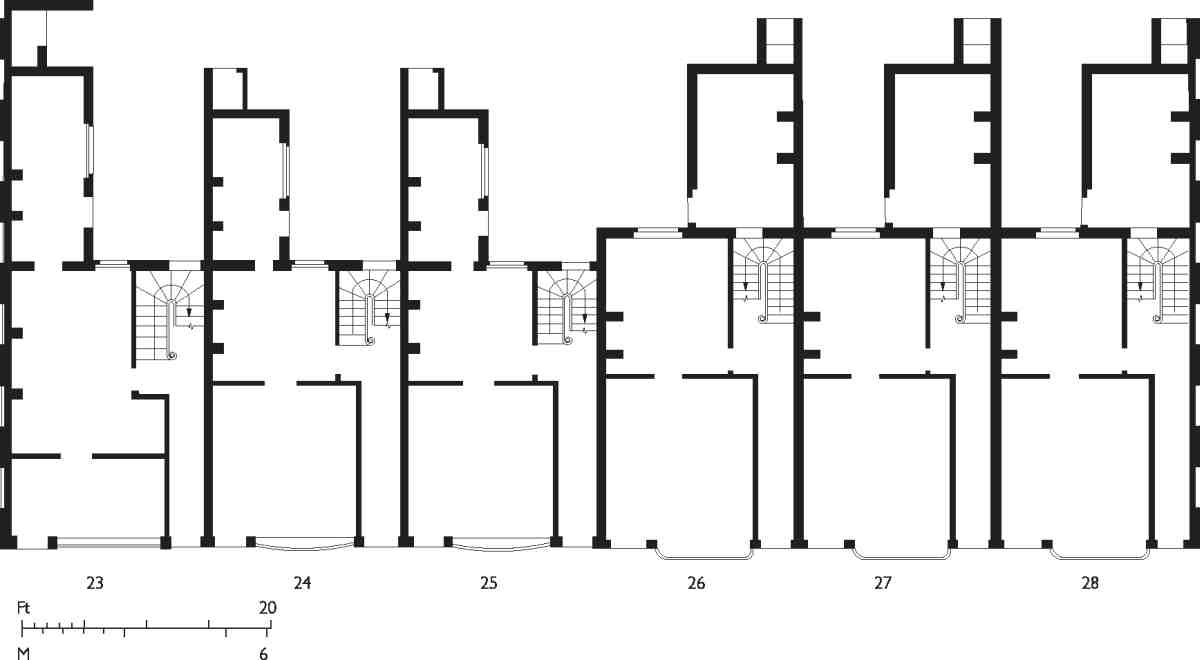

Typically the houses have two-bay fronts of 17 or 18 feet, and vary in depth between 27 and 30 feet, the standard tworoom rear-staircase plan providing interconnecting rooms, with wash-house and water-closet wings. They rise four storeys over basements and have round-headed groundfloor windows with first-floor blind arcading (Ills 260–4). There uniformity stops. The ground floors of Nos 39–49, Armsby's houses, were not given the rusticated stucco facing that was present elsewhere. The houses on the south and east sides built by Barkley, Priddle and Manser, and Harris (Nos 1–17, 22–30 and 34–38) do not have the stuccoed impost bands seen in various forms on the estate: reeded at Nos 54–57 (where Chapman kept to his Claremont Square type), corniced at Nos 18–21 and panelled at Nos 62–66. Stepping up in height and with 20 ft fronts, Nos 18–21 are rather bigger than their neighbours. They are also more finely detailed. Similar doorcases on Amwell Street seem to confirm a link between William and Thomas Oliver. No. 20, which appears never to have been sub-divided, retains simple but elegant internal door and shutter joinery with doubly rebated panels. Throughout the square there is great variety in doorcases and fanlights, rather less in the first-floor cast-iron balconies, most of which are of the anthemion type. Several street-corner houses have their entrances in stuccoed porches on their side-street returns; the porch on No. 67 was added in 1829 to mirror that on No. 66. No. 30 has a central-staircase plan, as does No. 2, not originally on a corner, but an exceptionally deep house that had a comparatively huge garden and a rear bay window, necessitating the non-standard layout. No. 22, a large square-plan re-entrant corner house, was extended in 1833–4 over part of its big garden. No. 58 is another large corner house with an unusual plan; the fanlight and balcony details give away its mid-1830s date.

Regularity was further broken in 1857 when the mansard roof on No. 64 was added, without the New River Company's consent, an alteration unique in the square. The addition of an upper storey on the side porch at No. 30 was among extensive lease-end repairs and alterations made by the company in 1909–14, carried out by several local builders under the supervision of C. S. Sanders. (fn. 47) The most significant change before the Second World War was the demolition of Nos 3 and 4 in 1938–9 for the widening and re-routing of Myddelton Passage.

On 11 January 1941 the north side of the square was bombed. Nos 43–53 were rebuilt in 1947–8 as flats behind a 'facsimile' façade— an early piece of reconstruction and a pioneering example of this approach. The work was probably overseen by Daniel Watney, Eiloart, Inman & Nunn. At the same time the square garden, which had become derelict during the war, was re-landscaped and rerailed, with a playground north of the church and a new paved layout to the east in what had become public gardens. (fn. 48)

263. Myddelton Square, reconstructed ground-floor plans

Social character and notable residents

One of the first householders in Myddelton Square, at No. 7 in 1826–7, was the actor, playwright and stage-manager of Sadler's Wells, Thomas Dibdin. (fn. a) But for the most part the early residents were members of the more mundane professions, particularly medicine and the law, or else merchants. Respectability was carefully guarded, by the inhabitants as well as the New River Company: in 1832 residents complained that boys using the square as a playground were 'dangerous and annoying'. The first tenant at No. 9 in 1825 was William Davies, who employed and boarded a few female 'tambour workers' (circular-frame embroiderers). Permission for this was seen as exceptional, the New River Company being anxious to keep away the lower forms of 'trade'. (fn. 49)

264. Nos 18–21 Myddelton Square (left to right), front elevation with doorcase and balcony details

Richard Carpenter, the developer of Arlington Street (now Way), was the first inhabitant of No. 62, from c. 1826 until 1842; his son, the architect Richard Cromwell Carpenter, also probably lived here through these years, during the first of which he was articled to John Blyth, with whom he may have worked on the parish school in Amwell Street. A lesser architect, John Bull Gardiner, lived at No. 67 in the 1830s and 40s, and William Slater, R. C. Carpenter's former pupil and partner, who took over the practice on Carpenter's death, lived at No. 54 through the 1860s. The square's suitability for architects found its way into fiction. In Peter Ibbetson (1892) George Du Maurier here installed Mr Lintot, a 'quite self-made' architect, and had him build himself an office in the garden. The locality was dismissively characterised as 'clean, virtuous and respectable'.

Du Maurier's description could doubtless have been applied earlier. Not only was the square then more solidly professional in tone, but there was some association with Methodism, going by the presence there of at least three important figures in the movement. Jabez Bunting, who completed the separation of the Methodists from the Anglican Church, lived at No. 30 from 1833 until his death in 1858, as a plaque records. (This house, subsequently enlarged, became a doctor's surgery and was later the estate office.) Another prominent Wesleyan minister, the elder John Hannah, was living at No. 8 in the early 1840s, and this house was subsequently occupied by the missionary Elijah Hoole, until his death in 1872. His son, also Elijah, a civil engineer and later prolific architect of Wesleyan chapels, lived there as a boy and young man. A rather less than respectable note was struck by the builder William Manser, who in the 1850s resided in the large corner house he had built at No. 22, together with his 'housekeeper' Isabella Priddle (probably his former partner's daughter), with whom he had two children. They were later married and moved to No. 17. (fn. 50)

Already by 1841 there were some skilled manufacturers in the square. No. 50 was occupied by two chronometermakers, Henry Appleton and Peter Birchall, and No. 16 by George Guillaume, a Swiss watchmaker. No. 71 had become a lodging house, its occupants including two Spanish merchants, and there were small schools for girls at Nos 40 and 63, run by Frances Muston and Martha Bowman. Lodging-house use gradually spread, but many houses remained in single-household occupation; No. 19 became a pub. Through the later nineteenth century those in the professions tended to give way to clerks and other white-collar workers, tradesmen and artisans. Among skilled workers watchmakers were prominent, with the names Guignard and Golay, noted Swiss watchmakers, occurring at Nos 11, 15 and 46. Whether Victor Piaget, a watch manufacturer at No. 48 in the 1860s, was of the same family as the famous firm of Piaget & Co. is not known. (fn. 51)

Other nineteenth-century names connected with the square are: Annie Abram, medieval social historian, born at No. 45 in 1869, the daughter of a law stationer; Golding Bird, physician and pioneer of electrical treatment, resident at No. 19 in the 1840s; Sir George Buchanan, epidemiologist, born in the square in 1831, son of a general practitioner; Stanley Lees Giffard, newspaper editor, first occupant of No. 39, where he stayed until 1857; Joseph Frederick Green, peace campaigner, born at No. 12A in 1855, the son of a merchant and JP; Edward Hughes, portrait painter, born in the square in 1832, the son of George Hughes, painter; Emily Nicholson, artist, resident at No. 70 in the 1840s. (fn. 52)

At the end of the century the erstwhile 'highly fashionable' square remained the best address in the area, characterized by 'ferns in china pots in windows'. (fn. 53) It was still middle-class, but from having been a residential quarter for families it was now mainly given over to lodging houses, largely inhabited by young professional men. Watchmaking and jewellery were fast disappearing. (fn. 54) In 1909–10 the young Fenner Brockway, then a journalist with the Independent Labour Party, moved here from the Claremont Mission settlement in White Lion Street, to lodge at No. 60, occupied by Alfred Harvey Smith, secretary of the ILP. The household included Smith's sister Lilla, later Brockway's wife, and drew in numerous young socialists. (fn. 55)

Multiple occupancy having long since become widespread, the outright conversion of the square's houses to flats began; the large corner house at No. 58 was converted in 1936. More flats were formed across pairs of houses, by cutting through party walls and replacing redundant front doors with windows. (fn. 56) The New River Company's conservative approach in this work was presented as exemplary in 1944, and appreciated for its recognition of the square's 'well-thought-out design' and 'already delightful rooms'. (fn. 57)

After post-war rebuilding on the north side, many more lateral conversions followed in the late 1950s and early 60s (Nos 5–9, 34–35, 54–55, 60–65). The writer B. S. Johnson lived in one of these, Flat 4 in No. 5, in 1965–9, during which time he produced some of his most important and uncompromisingly experimental work. By the early 1980s, when Nos 11–12, 15–16 and 39 were converted by the London Borough of Islington, there were relatively few undivided houses left. Most rear gardens had already been reduced in size by New River Company developments of the mid-century. (fn. 58) This tide was turning. In 1975 the City University acquired No. 20 as a house for its vice-chancellor, the lease prohibiting occupancy by more than one family, and in the 1980s Islington began to sell properties through 'right-to-buy' legislation. The square has now been partially re-gentrified, some sub-division being unpicked. One consequence of these changes is that the number of residents has declined significantly since about 1960. (fn. 59)

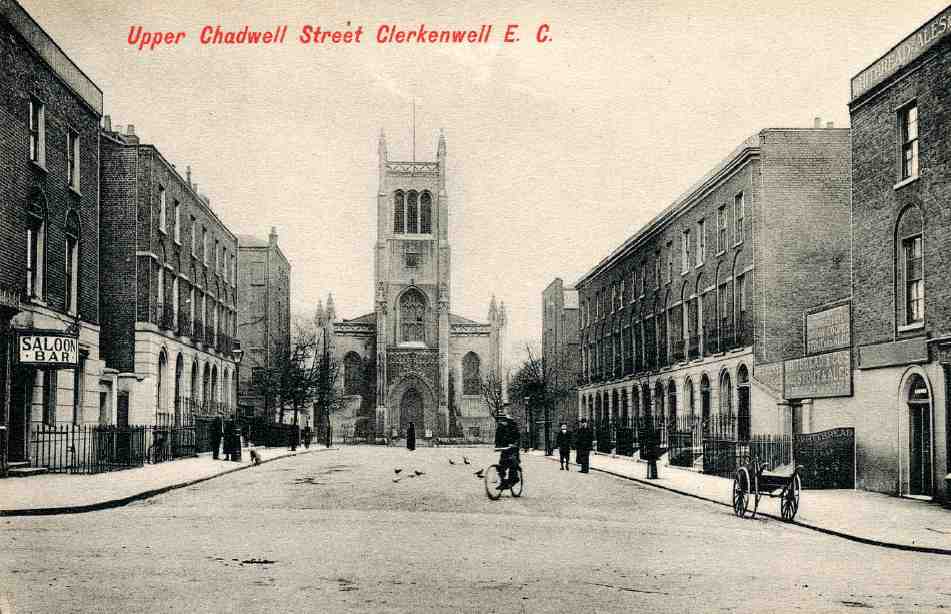

St Mark's Church

Built in 1825–7, St Mark's is a Commissioners' Church and characteristic of the genre, though the stone-faced west tower is a unexpectedly powerful composition. The interior has been greatly altered, most recently in a spartan remodelling of the early 1960s, following significant war-damage.

In 1818 the Commissioners appointed under the new Church Building Act approached the New River Company with a view to building a church in a square on the estate, but it was late 1822 before matters progressed. A site in the then nascent Myddelton Square, 'the most commanding, centrical and convenient situation', (fn. 60) was given by the company, subject to conditions. These included completion of the church within six years, its enclosure by railings, and a ban on burials. As it happened, burials were not prohibited outright but were discouraged through high fees. The company's request that its surveyor, W. C. Mylne, be employed as architect was agreed to, provided his plans were 'of a plain Gothic character'. (fn. 61)

This was the only church Mylne designed. He struggled to meet his brief, which called for accommodation for 2,000 at a cost of £15,000, confessing in 1823 that 'although plainer than almost any church I have seen executed in Gothic, the estimate exceeds in a small degree the stipulated amount'. (fn. 62) When the building was completed in 1827 the final cost was about £18,000, of which the parish contributed £2,000. (fn. 63)

265. St Mark's, Myddelton Square, from west in 1963

266. St Mark's, Myddelton Square, from south in 1966

Construction began in 1825 with the laying of a sixfoot-thick raft of lime concrete, which proved a cheaper option than conventional brickwork or piling. This was the work of Durant Hidson, not the main contractor Robert Streather (who built several of the Commissioners' churches in London). Hidson was credited by the Commissioners with the similar foundations at Millbank Penitentiary: devised by Robert Smirke and laid in 1817–22, these were the first of their kind in England, but the contractor was in fact Samuel Baker, who had perhaps employed Hidson. The decision to found the church in this way was made in the same month (April 1825) that Smirke and Baker began to underpin the partially collapsed Custom House with concrete foundations, a high-profile project that brought the technique wider acceptance. (fn. 64)

Faced in Bath stone and rising 94 ft on a hilltop, the view-stopping west tower is the chief feature of St Mark's (Ills 265, 271). In 1907 the church historian T. Francis Bumpus wrote that it 'is really of such excellent proportions and details that it is surprising how the same person could have designed anything so irremediably bad as the body of [the] church'. (fn. 65) He wrongly claimed that the fourstage tower was 'copied from that of Frampton Church, near Gloucester'. It is unlike those in either Framptonupon-Severn or Frampton Cotterell, but does incorporate features characteristic of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century churches in south Gloucestershire and north Somerset, notably the tight three-light belfry openings and cusped chevron parapets, which balance the scaled-up west entrance and openwork tracery panels. This pre-antiquarian Gothicism may have been informed more by local knowledge than by pattern books, for as a teenager in the 1790s Mylne worked in the area under his father on the Gloucester and Berkeley Ship Canal. However, as he nowhere else showed either such an understanding of Gothic forms or such architectural flair, it is indeed questionable whether the design of St Mark's tower can have been his own unaided work. (fn. 66) (fn. b)

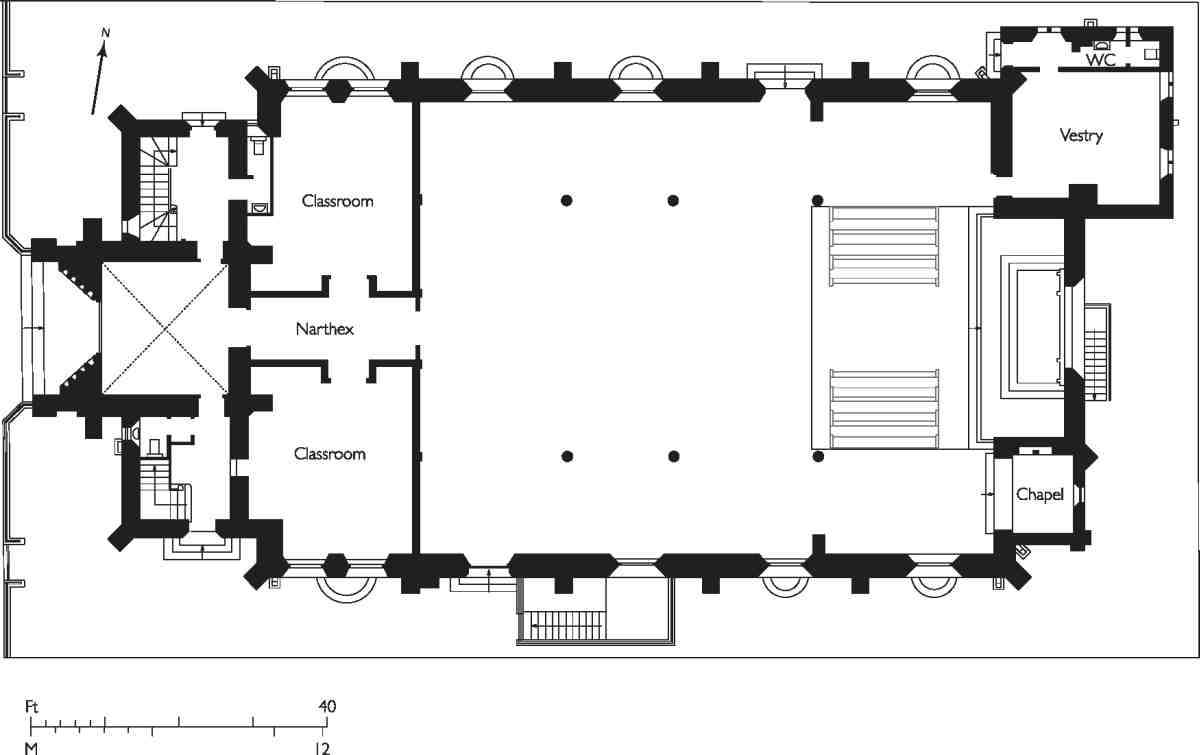

267. St Mark's, Myddelton Square, ground plan following alterations of 1939–40 and restoration of 1960–2

The stock-brick body of the church, in stark contrast, is certainly plain, and was soon criticized, by Edward John Carlos in the Gentleman's Magazine, for 'excessive clumsiness' and 'utter want of taste'. (fn. 68) In the gaunt side buttresses Bath stone gives way to Portland stone, reused from Wanstead House, Essex, and introduced at Streather's request (Ill. 266). The short chancel was originally flanked by small vestry rooms at the corners of the building (Ill. 267). There are cast-iron window frames, except in the largest openings at the east and west ends, which were given stone mullions, again at the request of Streather. (fn. 69)

The undivided interior stands over shallow-arched crypts. In the event it was built to house, 1,915, and originally had galleries on three sides, supported by cast-iron columns, for about 600. The west gallery, on twelve columns, was huge, with upper galleries for children flanking the organ. (fn. c) A triple-decker pulpit stood in front of the altar, and a flat diagonally ribbed plaster ceiling, unsupported across a 60 ft span, cut across the head of the east window, an original if odd arrangement. Patterned glass here was replaced with pictorial glass by William Warrington in 1851–2; this too has been replaced. (fn. 71)

In the 1870s the interior was given an ecclesiological overhaul (Ill. 268). Plans for re-ordering, which included the addition of an apse and a north vestry, were prepared by the architect William Slater, Carpenter's protégé, a churchwarden and resident of the square. Slater was working on this project when he died in December 1872. His partner, Carpenter's son Richard Herbert Carpenter, took over and obtained a faculty in 1873, but the work was deferred until 1879–82, and the apse abandoned. T. H. Adamson & Son were the builders. The church was reseated, the pulpit replaced to make way for a choir, and new tiled chancel steps, communion rails and a reredos were installed. In addition, the south vestry was replaced by a small side chapel, and a font was placed in the centre aisle. The font and the St Mark window in the south chapel commemorate the Rev. Henry Jones, vicar in 1872–8. Congregations having declined, the upper galleries were removed and the organ was brought down. (fn. 72)

268, 269. St Mark's, Myddelton Square, interior from west c.1900 (above) and in 2005 (below)

From a later generation there is a three-light window of 1912 in the south wall, by James Powell & Sons, depicting the Angel of Resurrection with SS Paul and Thomas, and commemorating the Rev. Richard Lockwood Giveen. Another south-wall window, its authorship unknown, shows the Annunciation and commemorates William Hackett (d. 1913). War-memorial embellishments on the pulpit were added in 1921. (fn. 73)

The Rev. Frederick John Dove, of the Islington building family, was vicar from 1932 to 1965, during which time he oversaw two major changes, either side of bomb damage in the Blitz. In 1939–40 the north and south galleries and some pews were removed, and a wall was put up under the west gallery. This permitted the formation of a 'narthex', housing the font and lined with reset Gothic dado panelling, between a classroom and a choir vestry. Thomas F. Ford was the architect, and W. Silk & Son Ltd the builders, the specification having been prepared by Dove Brothers. (fn. 74)

Within three months of the completion of this work, glass was blown out and the roof left unsafe by the bomb that wrecked the north side of the square. The main body of the church was closed to services until after a restoration of 1960–2, carried out by Doves under H. Norman Haines, architect. Six slim reinforced-concrete stanchions were inserted to support steel reinforcement of the original timber king-post truss roof. These stanchions were enclosed in fibrous plaster and given decorative 'capitals', and a new patterned ceiling and light fittings were installed (Ill. 269); the walls, stripped of plaster, were lime-washed. The font was moved again, with a new cover given by Dove. A new east window, re-using all of the original tracery, was made in 1962 by A. E. Buss of Goddard & Gibbs. It depicts the Ascension, with small panels below showing Sir Hugh Myddelton at New River Head, Dame Alice Owen, the Angel Inn and Sadler's Wells. (fn. 75)

Planning permission was refused in 1968 for a scheme, designed by Sir Basil Spence & Partners, to convert part of the building to a school. In 1972 the west gallery was enclosed to serve as the parish hall. The next year the church hosted a lecture and exhibition about transcendental meditation. It would not then have been foreseen that, just short of thirty years later, in 2002, the World Community for Christian Meditation would establish the London Christian Meditation Centre in the former west gallery. (fn. 76)

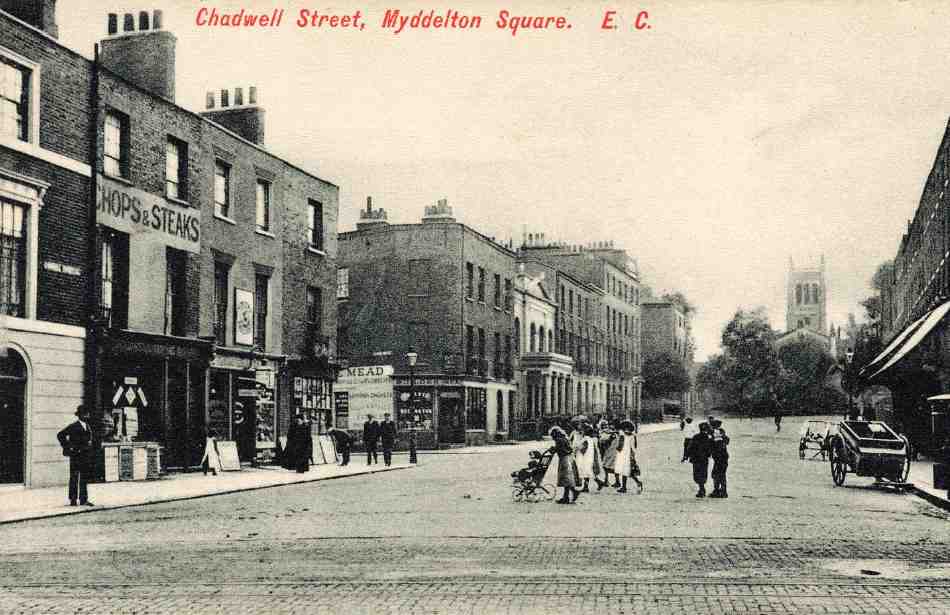

Chadwell Street

Named after one of the sources of the New River, Chadwell Street was begun in 1822, with agreements for the building of all but No. 11 made by 1823. However, the street was not fully built up until 1838, and there is a consequent lack of coherence (Ill. 270). The earlier developments were towards the east or St John Street end, and included a Nonconformist chapel of 1823–4. Shophouses at Nos 1–3 were built along with the adjoining St John Street frontage in 1822–4, Daniel Toohey, a victualler, being the developer. In 1823 James Hall, a Charterhouse Street plumber, undertook, in partnership with Charles Haynes, to build sixteen more houses, seven flanking the chapel at Nos 4–10, and nine more on the north side at Nos 15–23. Only Nos 4. and 5, with shops, and Nos 20–23, put up by William Pateman, another plumber and glazier, were completed before Hall's death c.1830. Then the principal builder on Hall's take was John Ramsay, who gave W. C. Mylne considerable difficulties with poor materials and construction. James Mansfield had taken the plots for Nos 12–14 in 1822, but deferred development into the 1830s, as did Priddle and Manser at No. 11 opposite. Both these builders held adjacent plots fronting Myddelton Square, and left the finishing of Chadwell Street until after the completion of their parts of the square. (fn. 77)

270. Looking west along Chadwell Street to Myddelton Square

Builders of the individual houses were: (fn. 78)

Nos 1–3. James Armsby or George Bishop, 1822–4

Nos 4, 5. James Hall, 1823–4

Chapel. Thomas Elliott, 1823–4

Nos 6–10. John Ramsay, 1829–32

No. 11. Thomas Priddle and William Manser, 1829–34

No. 12. James Mansfield and Sons, 1829–35

Nos 13, 14. Mansfield and Sons, 1835–8

Nos 15–19. Ramsay, 1828–30

Nos 20–3. William Pateman, 1824

The houses here are entirely typical for the area. On the south side, where the continuity is in any case broken by Arlington Way and the chapel, there is a step up from three to four storeys near the more desirable Myddelton Square end. The north side is all four-storeyed and more unified. However, while there is ground-floor rustication with square-headed windows on the south side and in Mansfield's group opposite, there is plain brick with round-headed windows on the ground-floor fronts of Hall's north-side development. The shop plots at the corners with Arlington Way (Nos 3 and 4) have irregular shapes, while the houses at the west end (Nos 11 and 12) are the largest, and have side-porch entrances (see Ill. 4), No. 11 having been built with a bow window to the rear. It also has an added attic.

No. 1 appears to have begun as a butcher's shop, and a baker, Thomas Reynolds, was the first occupant of No. 3. From 1826 he and John Reynolds ran a 'gentleman's academy' at No. 23 that had links with the London Gymnastic Institute (see Chapter IX). This and the adjoining house incorporated shops from 1878. No. 4 has a late nineteenth-century shopfront, and there is a restored early twentieth-century painted sign advertising 'Thomas B. Treacy Funeral Directors' on its Arlington Way return, behind which there is a single-storey former chapel of rest. No. 3, demolished c. 1978, was wholly rebuilt by Hugh Davies in 1993–7, in keeping with the street generally at the front, but refreshingly new to the rear. Other rebuilding has been more piecemeal. (fn. 79)

271. Looking east along Inglebert Street to Myddelton Square

Word Centre (formerly Angel Baptist Church)

This was built as Providence Chapel for a congregation of Calvinistic Methodists. Thomas Elliott, who had come to the New River estate in 1819 to build houses in Claremont Terrace (Nos 49–57 Pentonville Road), agreed to build the chapel in 1821 in what was then still a field. He deferred work until 1823–4, only proceeding once pressed by the New River Company, also erecting a house behind the chapel to face Arlington Way. (fn. 80)

In 1827 the congregation left for Rawstorne Street, and the building was taken over by former members of the new Scottish Presbyterian church in Regent Square who objected to Edward Irving's teachings. They too did not last, and further congregations came and went, including that of the Rev. Ridley Haim Herschell, a converted Jew. In 1853 the chapel was acquired by a Strict Baptist congregation and renamed Mount Zion Chapel. This occupancy lasted until 2002, the building latterly being known as Angel Baptist Church.

272. Angel Baptist Church, Chadwell Street, in 1991

The chapel followed the slightly earlier Claremont Chapel in Pentonville Road in the simple classical forms of its street elevation, though it is smaller and proportionally lower and wider in relation to the flanking houses (Ill. 272). The stucco facing and the Ionic porch may not be original, the porch being absent from a lease plan. (fn. 81) If so, they may have been among works undertaken for the newly settled Baptists in 1854–5, when Richard Minton was the builder. The doorways within the porch had their heads raised for fanlights over new doors, probably in 1894, and the outer portico columns have since lost their volutes.

Internally, alterations were made from time to time through the second half of the nineteenth century, and it is not entirely clear which features belong to which phase. The most prominent are the three-sided, panel-fronted gallery on slender cast-iron columns, and three pedimented aedicules on the end wall—one behind the former raised pulpit and the others framing doors to the vestries. These were probably installed at the same time as the baptistery, in 1854–5. The designedly open timber roof and match-boarded ceiling were probably made in 1872–3, and the glazed partition behind the vestibule was most likely fitted in 1894. Twelve gallery benches survive from a reseating of 1884, but the pews and raised pulpit of the same date were removed in 2004 as part of the conversion carried out for the present Pentecostalist congregation. (fn. 82)

Mylne Street

This short link between Claremont and Myddelton squares was named after the New River Company surveyor, more likely the deceased father, Robert, than the son, William Chadwell. Richard Chapman, who was responsible for the adjoining plots on both squares, agreed to develop both sides of the street in 1823, but it was only in 1828–9, once Claremont Square was otherwise complete, that he built the east side, Nos 1–5, along with No. 32 Claremont Square beyond a carriageway opening to Claremont Mews. In 1934–6 No. 1 was demolished to widen access to Claremont Close, and the fronts of the other houses were partially rebuilt. The two houses opposite were built in 1834–6 by James Fisher, who was then completing Myddelton Square on the adjoining plots to the south. This mirrored semi-detached pair is now in flats and numbered 6–11; the southern house was already divided in 1871. (fn. 83) It departs from the standard local type of the 1820s in both form and detail, revealing its later date in having slightly recessed three-storey entrance bays and cast-iron balconies to both ground- and first-floor windows, as well as by the absence of first-floor arcading. A cast-iron overthrow with a lamp bracket survives in front of the entrance to Nos 6–8.

Claremont Close

Hidden behind the east side of Claremont Square, Claremont Close occupies a site first developed in the 1820s as Claremont Mews, serving Claremont Terrace and the north side of Myddelton Square. (fn. 84) By the early twentieth century the mews had been largely converted to industrial use, but a few families were living there, in conditions that were condemned in 1929. The New River Company swept the mews away to form the present suburban-classical close in 1934–6 (Ill. 273), employing Lewis Solomon & Son as architects, and Henry Kent Ltd as builders. No. 32 Claremont Square and No. 1 Mylne Street were demolished to widen access. (fn. 85) Eight blocks of six flats curve round an oval lawn and flowerbeds, with elevations in a municipal neo-Georgian style. The two southernmost blocks (Nos 37–48) were heavily damaged in January 1941 in the same attack that accounted for the north side of Myddelton Square. They were rebuilt to the original plans and the close was otherwise restored in 1946. (fn. 86)

273. Claremont Close in 2005. Lewis Solomon & Son, architects, 1934–6

Inglebert Street

In 1818 W. C. Mylne intended to form a street off the north-west corner of Myddelton Square in continuation of what was to become Great Percy Street. Five years later the road was laid out further south, to align with the west front of the intended church. (fn. 87) First known as Upper Chadwell Street, to correspond with (Lower) Chadwell Street on the opposite side of the square, this short link to Amwell Street (Ill. 271) was renamed in 1935 to commemorate William Inglebert, who was involved with the engineering of the New River. The first houses were Nos 1–7 on the south side, undertaken by Edward Cowper Fyffe in 1823, but built in 1827–8 by Garland and Perkins. Nearest Amwell Street, No. 1 originally had a shop. Nos 2–6 retain good radial fanlights. On the north side a deep plot with the available frontage of about sixty feet was leased to Thomas Oliver for a yard behind his garden at No. 76 Amwell Street. For a time this remained undeveloped as the New River Company required easy access to the water main beneath, supplying the Upper Pond at Claremont Square (see also Nos 7 and 18 River Street). In 1830–2 Oliver built Nos 9 and 10 on part of the frontage (having failed to secure permission to squeeze in four narrow houses). The line of the main was not covered until 1839–40 when the wider (25 ft) house at No. 8 was built, displacing two stables that had been used by Oliver and Richard Carpenter. The first occupant of No. 8 was Henry Clare, a feather-bed manufacturer. (fn. 88) Nos 8–10 faithfully perpetuate the idiom of the 1820s, but with mansard attics. The yard to the rear of No. 8 was lined with garages until 2006–7 when it was redeveloped as Ingle Mews, a small cluster of houses built by Gannon Homes (UK) Ltd and designed by Oxford Architects. (fn. 89)

River Street

River Street also links Amwell Street and Myddelton Square, but departs from the otherwise square grid, so as to align with Lloyd Baker Street. When first laid out in 1823 it was called Fyffe Street, after the speculator Edward Cowper Fyffe who took on much of the frontage, along with the east side of Amwell Street (see above). His bankruptcy in 1824 put paid to what would have been a departure from the New River Company's usual selfregard in naming streets. Responsibility for the development of the north side passed from Fyffe to Garland and Perkins, who built the eleven houses at Nos 14–24 in 1825–7. Agreements to develop the south side had also been made in 1823 and 1824, Fyffe taking on the west end (Nos 1–3), and William Harris the rest. On Harris's frontage John Ramsay built Nos 8–12 in 1824–7. John Scott, the brickmaker of No. 16 Claremont Square, built Nos 2 and 3 in 1826–7, Nos 4–7 in 1827–8 and No. 1 in 1828–30. The single-bay house infilling the west end (No. 25) was built in 1838–40 by Richard Pulford. Mansard attics were added to Nos 20–23, starting with No. 21 in 1841. (fn. 90)

The houses of River Street, which are typical of the estate in the 1820s, have three storeys, except at No. 24, which has two, and No. 12, which has four. In the lowerstorey stucco facing, the rustication has narrower bands on Ramsay's houses at Nos 8–12, and there are stucco impost bands and a cornice on the north side, but not on the south side. Several margin-glazed ground-floor windows survive. No. 25 maintains the 1820s treatment on its lower storey, but not above, introducing stucco architraves. As elsewhere, front walls have seen much rebuilding, notably at No. 7, which, like No. 18, breaks forward slightly over a widened carriageway on the line of the New River Company's main to the Upper Pond.

The carriageway at No. 7 gave access to a mason's yard, occupied by John Scott from 1831 and later by William Spencer Dove, the founder of the building firm, who rebuilt a workshop here in 1852. The northern carriageway at No. 18 did not serve an equivalent yard until the early 1930s when sheds were built by the New River Company. These have been replaced by lean-tos, now numbered 18c. (fn. 91)

Arlington Way

274. Nos 23–28 Arlington Way, reconstructed ground-floor plans

Arlington Way follows the line of a cross-field path that ran from upper St John Street (then St John Street Road) to Sadler's Wells and, via a bridge over the New River, to Sir Hugh Myddelton's Head, New Tunbridge Wells and New River Head (Ill. 239). It was briefly called Arlington Place, and then, until 1936, Arlington Street; the significance of the name Arlington in this context is unknown. The street was not part of Mylne's layout in 1818, but the plans changed and it was built up in 1822–4 with seventeen fourth-rate houses on each side, of which Nos 18–28 on the east side survive (Ills 274 and 275). The developers were Thomas Richard Read and Richard Carpenter in partnership.

275. Nos 18–27 (left to right) Arlington Way in 2005

Nos 18–22 Arlington Way were built by Henry Johnson and John Trigg for Carpenter, Nos 23–25 by William Pateman, a Goswell Road plumber who took No. 23 for himself, and Nos 26–34 by Samuel James Buckingham, variously described as a bricklayer or plumber. (fn. 92)

This street was always commercial and relatively humble in character, maintaining the earlier path's function as an approach to places of entertainment. With three storeys and 15–16 ft plain-brick fronts, the houses here are small by comparison with other surviving developments on the New River estate, though they were given small rear wings behind the standard two-room plans. The blind arcading ubiquitous on the estate's better houses is absent, as on Myddelton Street. Most of the east side incorporated shops from the start, balancing those being built at the same time on Amwell Street, the other flank of the estate as far as it was laid out in the 1820s.

An original bowed shopfront survives at No. 26, though wholly reglazed and with its part-glazed shop door boarded up. First leased to a tailor, James William Cooke, who also had Nos 5 and 29–34, this building was occupied by Samuel Marston, a cooper and then an undertaker, from about 1835 into the 1870s. Where they were not shopkeepers, early occupants in the street were engaged in trades including gem-cutting and ivory-working, often in sub-divided houses; in 1841 No. 26 housed twelve people, in Marston's and two other households. The public house at No. 27 was a beer house from c. 1848. It was known as the Harlequin by 1894 when its pilastered front was made by S. Inkpen & Son, for Mann, Crossman & Paulin, brewers.

276. Arlington House, Arlington Way, in 2005. 'Unity' flats built in 1958; entrances altered 1987

At No. 22 is a carriageway to what was originally a livery-stable yard, now occupied by No. 22A, an office/studio building of c. 2001 attached to No. 381 St John Street. Above the shopfronts there has been much rebuilding of the front walls, at Nos 21 and 22 in 1901–2, and Nos 23 and 26–28 in 1908–9. As Sadler's Wells expanded so Nos 29–34 were acquired and demolished in the 1930s and 1980s, No. 28 surviving as a part of the rebuilt theatre's premises. (fn. 93)

The west side of the street was entirely redeveloped in the twentieth century. At the south end the Shakespeare's Head (No. 1), a beer house from the 1850s, was rebuilt in 1949–50 by W. Loweth & Sons, to plans prepared in 1938–9 for Courage & Co. (fn. 94) The New River Company replaced Nos 2–16 in 1958 with two lowrise blocks of two-bedroom flats, Arlington House (Nos 1–15) and Nos 16–19 (Ill. 276). In a break with its early post-war preference for brick-built blocks of flats the company adopted system building. Kendrick Findlay & Partners, the architects, were associated with Unity Structures Ltd, the builders, whose Unity construction was a widely used concrete-block prefabrication system. The 'rationalised traditional' form used here was introduced in 1957 for two-storey blocks, built with concrete slabs, brick cross-walls and prefabricated timber nonstructural walls and roof trusses. The development included eleven garages in what had been the garden of No. 22 Myddelton Square. (fn. 95) To the north stood a house (No. 17) attached to the back of the chapel on Chadwell Street, to whose congregations it belonged. In 1929–30 the Baptists replaced it with a school. This plain but wellproportioned red-brick neo-Georgian building, No. 7, was designed by Herbert A. Wright of Pentonville Road, and built by J. Webb & Son. It continues in use as a Sunday school, with offices for the Association of Grace Baptist Churches. (fn. 96)

Myddelton Passage