A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for the Institute of Historical Research, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Henley: Origin and Development of the Town', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16, ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp31-49 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Henley: Origin and Development of the Town', in A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Edited by Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp31-49.

"Henley: Origin and Development of the Town". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 16. Ed. Simon Townley (Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2011), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/oxon/vol16/pp31-49.

In this section

ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE TOWN

Origins and Pre-Urban Topography

Prehistoric, Iron-Age and Romano-British activity in the south-west Chilterns is well attested, and from an early date there was probably a ford at or near the site of the town. (fn. 1) The earliest unequivocal evidence of settlement is a substantial, possibly two-storeyed Romano-British building excavated west of Bell Street, with associated 2nd-century pottery. The site lay close to the Roman road from Dorchester, but whether it formed part of an isolated farmstead or of a more significant settlement near the river crossing is unclear. (fn. 2) More Roman pottery, daub and burnt flint has been found south-west of the market place near Rotherfield Court, in an area known by the 16th century as 'Ancastle'. (fn. 3) No other archaeological evidence of Roman or early Anglo-Saxon occupation has yet been found.

By the 8th century Henley belonged to the large royal estate centred on Benson, and was retained by the king long after surrounding areas such as Badgemore, Bix and the Rotherfields were granted to local lords. (fn. 4) Presumably this reflected the importance of the river crossing and, perhaps, the usefulness of the riverside meadows and of the upland wood-pasture which gave Henley its name. (fn. 5) Isolated pottery finds of the 7th–8th and 11th–12th centuries (fn. 6) may indicate a small rural settlement on or near the site of the modern town, and by the 1140s, when King Stephen almost certainly issued a charter at Henley, there may have been a small royal lodge or home farm on the site of Phyllis Court and Countess Garden, near the river crossing. Possibly there was a chapel on the site of the present church, since by 1200 Henley church was virtually independent, and the churchyard seems not to fit well with the planned layout of the medieval town. (fn. 7) The evidence is inconclusive, however, and the form and location of any such settlement is unknown.

The date and circumstances of the town's creation are unrecorded, although it was well established by the 1260s–70s when it had a merchant guild and was occasionally called burgus. (fn. 8) Circumstantial evidence points to a late 12th-century foundation by Henry II, who laid out New Woodstock around the same time. (fn. 9) In 1177–8 Benson manor (including Henley) fell back into royal control after a long lease, and the same year the king acquired land at Henley 'for making his buildings'. Possibly this referred to urban development, although as the resulting decay of rent was only 2s. 6d., more likely it referred to the building or rebuilding of a royal manor house. (fn. 10) Around the same time the bridge appears to have been built or rebuilt in stone, (fn. 11) and a fair grant was acquired between 1199 and 1204, possibly in an attempt to capitalize on Henley's new urban status. (fn. 12) Then or soon after, the town was detached from the rest of the Benson estate in Henley as a separate 'Henley manor', which was later held with the park and a few small pieces of agricultural land. The town's layout is consistent with such a date, and clearly it thrived, since by the early 14th century it had been extended northwards along New Street. Despite its urban character and increasing self-government through the guild, however, its status remained undefined until the acquisition of a royal charter in 1568. Usually it was referred to as a villa rather than a borough, and throughout the Middle Ages it remained a seignorial town theoretically subject to the lord's manorial jurisdiction. (fn. 13)

The Medieval Town

Planned Layout and Burgage Plots

Early layout

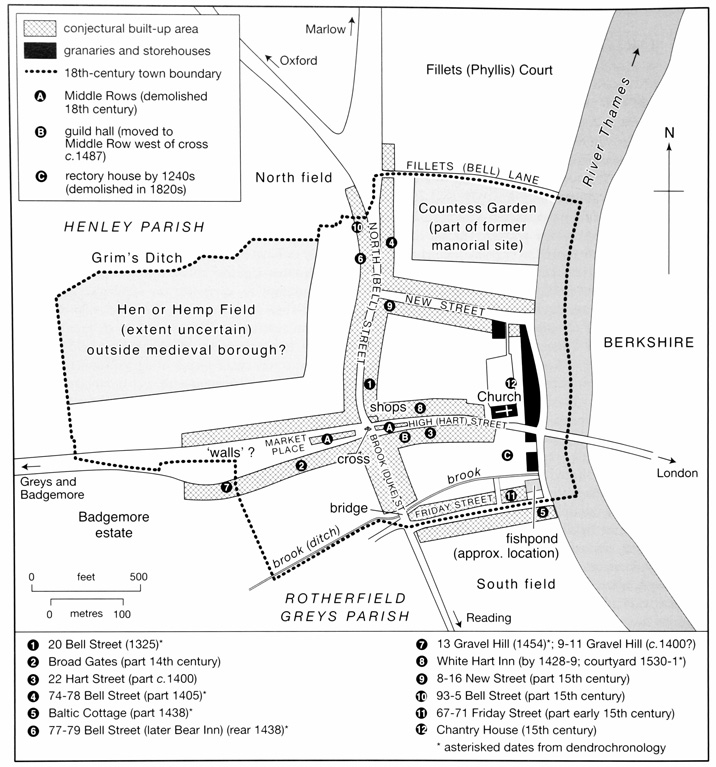

As first laid out, the new town probably comprised a wedge of land focused on the main crossroads, bounded on the east by the river Thames and on the south by the town brook or ditch, which flowed into the river just north of Friday Street (Fig. 7). The western boundary abutted the separate manor of Badgemore, while the northern one may have followed Grim's Ditch, part of an Iron-Age earthwork which ran probably along the line of New Street. Beyond there was the manorial enclosure, probably originally incorporating the sites of both Countess Garden and Phyllis Court. (fn. 14)

7. Medieval Henley: a conjectural reconstruction of the town c. 1400, showing the location of some important surviving medieval buildings. (Adapted from a map by R. B. Peberdy)

The town's street plan was simple, comprising an east–west road from the bridge which intersected the sinuous north–south route from Dorchester to Reading, before opening out into a large wedge-shaped market place. Beyond there, the road presumably continued (as later) up what became Gravel Hill, running on to Badgemore and Greys Court. Though possibly rerouted, both roads almost certainly pre-dated the town, the wide wedge of the market place perhaps incorporating an earlier funnel-shaped droveway leading to the river. Throughout the Middle Ages, the street leading northwards from the crossroads was called North Street, and that leading southwards South or Brook Street (from the town brook). The former became known as Bell Street (from the Bell Inn at its northern end) by the 17th century, while the latter became Duck and later Duke Street, probably both corruptions of Ditch Street. (fn. 15) The name Hart Street (for the road from the bridge to the crossroads) was established by the 1660s, after the White Hart inn on the street's north side; (fn. 16) earlier, the whole length of Hart Street and Market Place was known as High Street. (fn. 17) The name Northfield or Northfield End, for Bell Street's northern end beyond the town, was recorded from the 15th century, replacing the earlier Old field, Aldfeld or Naldefeld. (fn. 18)

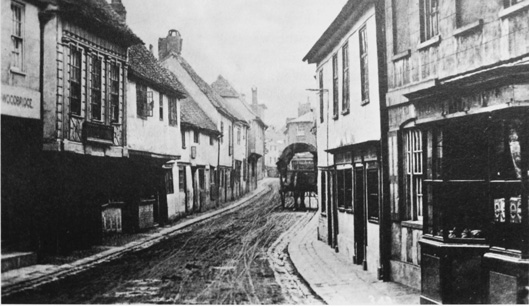

8. Duke (formerly Brook) Street in the 1860s, looking north. The street was considerably narrower than the other main streets of the planned town, until widened in 1872–3 by the demolition of its west side.

Measurement of the burgage plots which survived in the 19th century (fn. 19) suggests that those along High Street were originally 1½ perches wide and 19–23 perches long (7.5 m. by 96–161 m.). Those lining Bell Street were quite different, probably 2 perches wide and 10–16 perches deep (10 m. x 50–80 m.); nonetheless, their regularity and location on a major through-route imply that they were part of the original plan, rather than a later phase of back-plot development. By contrast the small, irregular plots fronting Duke Street seem to be a later imposition, cut piecemeal (presumably for profit) from the long, planned burgage plots running south from Market Place and Hart Street. The process was well established by the early-to-mid 14th century, when Duke Street seems to have been built up as far as the town ditch. (fn. 20) A further indication that this was an unplanned extension was the street's unusual narrowness (in places only c. 15 ft). Only in the 1870s was it widened to its present dimensions, by the demolition of its entire western side. (fn. 21)

Before its enlargement in the 18th and 19th centuries, the churchyard occupied a plot c. 51.5 m. wide (approximately 10 perches), immediately behind the river frontage. Its dimensions bear no obvious relationship to the regular plot-series to the west, perhaps implying that it pre-dated the planned town. The churchyard's encroachment into the street (more pronounced before 18th-century road widening) is an unusual feature with few parallels, (fn. 22) but may have been seen as an advantage, helping to control access into the market place and ease the collection of tolls, much like the bars recorded at the opposite end of Market Place on Gravel Hill in 1472. (fn. 23) By contrast, the rectory house curtilage on the south side of Hart Street fits well with the medieval design, apparently occupying four 1½-perch plots amalgamated to form a 6-perch unit. Possibly these were allocated by the Crown soon after the town's creation, providing a dwelling for the rector immediately opposite the church. A rectory house on the site is documented from the 1240s, and in the early 14th century the rector extended the curtilage southwards to Friday Street, through piecemeal acquisitions. (fn. 24)

Between the north side of the market place and Grim's Ditch lay an area of agricultural land called Hen-, Hem- or Hempfield, one of several small fields on the town's fringes which presumably survived from before the town's creation. (fn. 25) By the 14th century, several houses fronting the market place here had adjoining strips of land in Henfield, extending some 272 m. (54 perches) northwards up to Grim's Ditch. (fn. 26) Not all the field can have been divided into private plots, however, since in 1423–4 the guild paid for a common gate and stile into the field, and for a public way 'in tempore aperto' (presumably when it was thrown open for grazing). (fn. 27) The field was still mentioned in 1587, (fn. 28) and was perhaps only fully absorbed into the town during its westward expansion along Gravel Hill in the 16th and 17th centuries. Part of it probably occupied land bought by the corporation in 1651, and known later as Townlands. (fn. 29)

New Street and Late Medieval Expansion

During the 13th and 14th centuries the town's success prompted several extensions, some planned and others more spontaneous. The small irregular plots on the north side of Friday Street originated probably as an area of squatter settlement south of the town ditch, laid out perhaps along a pre-existing track or droveway. By c. 1300 the street's north side had been incorporated into both town and parish, although its south side remained in Rotherfield Greys until the 19th century. (fn. 30) That side too was built up probably by the 1450s (when it comprised a tithing of Rotherfield Greys manor), and certainly by the early 16th century. (fn. 31) The street's name, established by 1305, derived probably from fishponds at its eastern end, fish being associated with Friday fasting; the fishponds (fed by the town ditch) certainly existed by then, and were partly acquired for the rectory house. (fn. 32)

The development of New Street and the town's extension northwards to Bell Lane (then called Fillets Lane) look more planned. New Street, probably following the line of Grim's Ditch along the southern edge of the manorial inclosure, was laid out before 1307, when it was already built up with adjoining houses. (fn. 33) The plots on its south side seem to have been developed first, carved from the rear of the existing plots running back from Hart Street, and measuring 3 perches wide by 12 perches long (c. 15 m. x 60 m.). The north side was built up presumably after the manorial site in Countess Garden was abandoned in the earlier 14th century, (fn. 34) the plots there measuring 4 perches wide by 13 perches deep (20 m. x 65 m.). The north end of Bell Street (towards Northfield End) was developed probably around the same time, first with regular plots on its west side (measuring apparently 3 perches by 11, or 15 m. x 55 m.), and later with piecemeal development along its east side. The latter process was underway by 1349, when there was a house on the southern corner of Bell Street and Bell Lane. (fn. 35) By then, and probably long before, the borough boundary had been moved northwards to run along Bell Lane, taking in the new developments. (fn. 36) Beyond the town, a triangular area (later built up) in the angle of Northfield End and Marlow Road may have formed a small open green fronting the entrance to the manor house. (fn. 37)

Piecemeal expansion westwards up Gravel Hill, beyond the market place, is illustrated both by mid 14th-century references to houses straddling the boundary between Henley and Badgemore, and by surviving early 15th-century buildings on Gravel Hill's south side. (fn. 38) Further south, the area between the town ditch and Greys Road may also have been partly colonized by small-scale squatter settlement during the Middle Ages; no evidence survives, however, and, unlike Friday Street the area remained outside the borough. One consequence of the various extensions is that Henley had no back lanes; access to back plots seems to have been chiefly through side passages, and by the 19th century some houses had no external back access at all. (fn. 39)

Medieval Urban Development

Shops on High Street and around the central crossroads are recorded from the early 14th century, (fn. 40) one of them at the crossroads' north-east corner with an adjoining shop to its north, and a 'messuage' to its east. (fn. 41) Some were described as 'selds' (selda), but as one in 1346 had a solar above, they were clearly substantial structures. (fn. 42) A Middle Row west of the crossroads, running up the centre of the market place, existed by the 1330s, its north side known later as Fisher Row, and its southern side (containing the shambles) as Butcher Row (Figs. 7 and 24). (fn. 43) A similar row in the middle of Hart Street was probably built up around the same time. (fn. 44) The crossroads itself had a market cross by 1308, which by 1422 had a shingled roof and housed the common bell. (fn. 45) In the early 15th century the guildhall stood on the south side of Hart Street a little way east of the crossroads, but c. 1487 a new hall was built in the Middle Row in the market place, with shops adjoining, and possibly, as later, a ground-floor town gaol a little further along. (fn. 46) By then there were also some major inns along Hart Street, in particular the White Hart (recorded from 1428–9) and the Catherine Wheel (recorded from 1499), (fn. 47) while a tavern at the crossroads in one of the Middle Rows was mentioned in 1357. (fn. 48) A few medieval buildings survive around that central area, most notably 20 Bell Street (dendro-dated to 1325), 20/22 Hart Street (partly c. 1400), and the Old Broad Gates (probably 14th-century) south of the market place. (fn. 49)

No shops were explicitly mentioned elsewhere in the town, whose western edge, beyond the market place, retained a rural flavour. A barn there was mentioned c. 1405, backing onto Henfield, (fn. 50) and here the boundary with the agricultural land beyond was marked by 'walls', presumably low earthen banks designed to keep out livestock. (fn. 51) Even so houses spilled over the town boundary by the early 14th century, and a run of surviving small houses on the south side of Gravel Hill was built in the earlier 15th century, perhaps for craftsmen processing rural produce in the upper market place. (fn. 52) Despite the intensive development, a few vacant plots of land remained dispersed throughout the town, even before the Black Death. A placea in High Street was mentioned in 1337, (fn. 53) and there were others in Friday Street, New Street and Northfield End. (fn. 54)

The waterfront north and south of the bridge was lined with granaries by the 14th century. In 1354 one had a cellar built into the bridge arch, while others stood at the riverside end of New Street and further south towards Friday Street. (fn. 55) A rare survival of a commercial riverside building may be the so-called Chantry House, built probably in the later 15th century in an area which, by the 1440s, included several granaries and a wool house. (fn. 56) Also adjoining the bridge by 1405 was a small freestanding chapel dedicated to St Anne, and by the 1490s there was an associated hermitage, standing apparently on or near the site of the later Angel Inn. A nearby almshouse existed by 1453. (fn. 57)

In the 15th century and presumably earlier the guild sought to regulate the urban environment through periodic byelaws. Butchers were forbidden to slaughter animals outside the market area or to leave animal heads, blood or offal in the streets, while in 1432 piles of timber, firewood or dung were not to remain in the High Street for more than eight days. (fn. 58) The usual attempts were made to control stray animals, especially pigs: a pound was repaired or constructed in 1422, and fines were enforced against the animals' owners. (fn. 59) In 1473 inhabitants whose property adjoined the town ditch were required to scour it, and latrines over the ditch were forbidden. (fn. 60)

Urban Development c. 1550–1700

The town's appearance in the 1690s was captured in a series of paintings by the Flemish landscape artist Jan Siberechts (Plates 3–4). These depict a densely built town still dominated by close-packed and largely timber-framed buildings, although by then the introduction of brick and new classical styles was beginning to change Henley's visual character. (fn. 61)

Despite sustained population growth there was apparently only limited extension of the built-up area during the 16th and 17th centuries. On the north there may have been small-scale expansion along the Fair Mile, where a house or inn with a bowling green was mentioned in the 1630s (fn. 62) and where a Quaker meeting house was established in pre-existing cottages in 1672. (fn. 63) Expansion southwards was constrained until the 1860s by Rotherfield Greys' open fields, (fn. 64) although a Congregationalist meeting house was established in a barn on the Reading road in 1672, and was rebuilt in 1719. (fn. 65) Scatters of cottages nearby and along part of what became Greys Road perhaps also originated in the 17th century. (fn. 66) West of the market place up Gravel Hill, areas of manorial waste were built up around the same time. Seven cottages on the site of the common dunghill, above the market house and corn market, were built apparently between 1605 and 1609, presumably forming part of the island of buildings behind the modern town hall, (fn. 67) and other houses on the lord's waste on the hill were mentioned later in the 17th century. (fn. 68) Land at the top of the hill, lying probably outside the medieval borough, was bought by the corporation for charitable purposes in 1651, but seems not to have been built up until becoming the site of the new parish workhouse in 1790. (fn. 69) By then there were houses nearby, and along much of the length of Gravel Hill and West Street. (fn. 70)

Within the town itself there seems to have been increasing density of settlement, both around the central market area and waterfront and along the smaller side streets. In 1591 the shambles in the Middle Row (adjoining the guildhall) incorporated seven shops, (fn. 71) with an open area to the west (80 ft by 35 ft) where 'foreign' butchers could set up stalls on market and fair days. (fn. 72) A malt mill nearby (near the common dunghill) was mentioned from 1588, (fn. 73) and workshops (oficina) adjoined the market cross in the 1590s. (fn. 74) A covered market house on the site of the present town hall was probably also of 17th-century origin. (fn. 75) Subdivision of houses was mentioned occasionally throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, (fn. 76) along with conversion of outbuildings (including brewhouses, barns and a gateway) into domestic accommodation. (fn. 77) The period also saw the beginnings of some of the cottage yards or courts behind the street fronts, which became such a significant feature of the 19th-century town. Three houses 'in the alley in Friday Street' were mentioned in 1680, and tenements in 'the court' in Friday Street in 1682, (fn. 78) while a group of four houses on Duke Street, let to tenants by the maltster Humphrey Newbury in the 1660s, was perhaps an early cottage row. (fn. 79) Such processes continued throughout the 18th century, and into the 19th. (fn. 80)

Near the bridge, the chapel of St Anne was demolished presumably at the Reformation. (fn. 81) A 'new tenement late builded upon the bridge' (later the Falcon inn) was mentioned in 1587, (fn. 82) and Siberechts' paintings show several buildings still clustering around the bridge's northern side, one of them built out into the water on stilts. The medieval hermitage just south of the bridge became a house, perhaps incorporating part of the nearby 15th-century almshouse; (fn. 83) both probably occupied the site of large gabled buildings with chimneys shown by Siberechts, which were later rebuilt or remodelled as the Angel on the Bridge Inn. The White Horse on the Bridge, established probably by the 1620s, appears to have been distinct from both the Falcon and the Angel, and was demolished with neighbouring buildings when the bridge was rebuilt in the 1780s. (fn. 84) Another small plot at the bridge's west end was 'lately built upon' in 1723. (fn. 85)

Most of the waterfront itself remained built up with granaries and warehousing, (fn. 86) and wharfs were mentioned frequently. (fn. 87) By the mid 17th century the most substantial was probably that between New Street and Phyllis Court, which belonged to Phyllis Court manor and was known later as Fortune's, Hawkins's or Eylsey's, from a succession of 17th and 18th-century tenants. (fn. 88) In the mid 18th century and possibly earlier this was the only wharf with a proper campshot and a crane, (fn. 89) and by the 1760s there was a pub there called the Ship. (fn. 90) Some other wharfs, however, were apparently little more than small riverside plots let to tenants. In 1628–9 the corporation staked out and leased for 13s. 4d. a 'parcel of void or waste ground or wood wharf' between Friday Street and the bridge, which adjoined a wharf in separate occupancy. (fn. 91) Siberechts' paintings show only a gently sloping shoreline along that stretch, while Jennings' wharf to the south of Friday Street, owned by the Stonors of Stonor Park, was shown as an area of flat riverside meadow with timber stacked up for collection. Another small wharf 'at the bridge foot' was left by a maltster to his daughter in 1726. (fn. 92) The stretch north of the bridge, from the Red Lion to New Street, was claimed by the grammar school trustees, who demanded wharfage dues there in the 1670s. That stretch too had only a sloping shoreline in the 1690s, though barges continued to unload there throughout the 18th century, when there were short stumps for tethering and a short campshot the length of a barge. A campshot built outside the Red Lion c. 1700 by a prominent Henley bargeman was removed on the orders of William Whitelocke, who, as lord of the manor, claimed rights over the river bank. (fn. 93)

9. Hart Street in 1826, looking east towards the bridge (rebuilt in 1786) and church. Medieval buildings down the centre of the street had been removed some sixty years earlier, followed by further improvements under the 1781 Bridge Act.

New public buildings included Bishop Longland's almshouses at the east end of Hart Street (built c. 1538–47), and the Newbury-Messenger almshouses east of the churchyard (c. 1669–72). The so-called Chantry House to their south, built probably for commercial use, became a school house before 1552, occupied from the early 17th century by the newly founded grammar and Periam schools. (fn. 94) Probably also in the 17th century, the guildhall acquired the large domed cupola or lantern shown by Siberechts in 1698. Several important new inns were also established, some of them well away from the main market area. The Bell at Northfield End was mentioned from c. 1592, and the Bear, a little way south on Bell Street, from the 1660s, though both may have had earlier origins. The Red Lion, at the north-east end of Hart Street between the church and the river, was an inn by the mid 17th century. Further west along Hart Street, the medieval White Hart was rebuilt on a courtyard plan in 1530–1, while the Catherine Wheel continued nearby. (fn. 95)

The corporation's continuing attempts to improve urban sanitation suggest that obstructions and nuisances remained endemic, as in most 16th and 17th-century towns. (fn. 96) In 1590 an inhabitant contracted to remove dung and soil from the common dunghills for his own use, and to clear dung heaped up by householders in front of their houses once a year, while in 1651 the corporation paid to have 52 loads of 'soil' carried away. (fn. 97) As in the 15th century, fines were instituted for leaving dung, straw or waste in the streets, (fn. 98) and inhabitants were sometimes prosecuted, for example in 1691 when a farrier dumped two cartloads of dung and building rubble in Bell Street. (fn. 99) Fines against wandering livestock continued: (fn. 100) in 1669 an inhabitant was paid 1s. for 'keeping hogs out of the churchyard', while in 1742 hogs and pigs in the streets were to be impounded by the town sergeant. (fn. 101) Scavenging was overseen by elected surveyors of highways, who also had responsibility for road repair. (fn. 102) In 1620 the town's streets were 'much broken, worn and annoyed with great holes', which was blamed on the turning of carts carrying corn, grain and malt to and from weekly barges; inhabitants were ordered to park their carts lengthways along the street, and to use planks to help with loading. (fn. 103) Even so, in 1661 rutted streets tipped over Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke's coach, throwing his wife 'into a dirty hole'. (fn. 104)

Improvement and Early Growth c. 1700–1850

Between 1700 and 1850 Henley was transformed by London-influenced rebuilding in brick (fn. 105) and by large-scale public works. Both reflected its emergence as a coaching and social centre, alongside its continuing roles as a market and riverside port. Piecemeal improvements began in the early and mid 18th century, but the most important followed the corporation's acquisition of the Henley Bridge Act in 1781. (fn. 106) Besides enabling rebuilding of the bridge, the Act facilitated wide-ranging improvements to its approach roads and to the waterfront, encompassing street widening and street lighting, clearance of market place encroachments, and the building of a new town hall. Related improvements continued into the early 19th century under a series of successor Acts. (fn. 107) Less desirable was the intensified development of cramped cottage yards as the population rose, and from the 1820s similar pressures prompted the building of Henley's first small-scale working-class suburbs, particularly along West Street, Gravel Hill, and around Greys Lane. By 1847 growth in that last area was sufficiently dense to prompt the building of Holy Trinity church.

Urban Improvement and the Bridge Acts

Though not promoted by the town, one of the earliest improvements was landscaping of the Fair Mile, the broad straight road leading into the town from the north-west. Sir Thomas Stapleton of Greys Court reportedly planted an avenue of elms there in 1751, (fn. 108) and the name Fair Mile seems to have been coined around that time, appearing on maps by the 1760s. (fn. 109) The present flint and brick wall on its north side (enclosing Henley park) was built by Strickland Freeman c. 1805–20, (fn. 110) but possibly replaced an earlier wall. The wide verges on either side belonged to Bensington manor as part of the manorial waste, and were still used for grazing in the early 20th century. (fn. 111)

Within the town, the row of buildings in the middle of Hart Street was demolished c. 1765, partly to improve access. (fn. 112) The market cross at the crossroads, possibly part medieval, was removed at the same time and its materials sold off, retaining only the bell and its covering, an attached whipping post and signposts, and a lamp at the top. (fn. 113) Before 1788 it was replaced by a tall stone obelisk inscribed with road distances, to which lamps and a pump for washing down the market area were added later (see frontispiece). (fn. 114) A weighing engine for laden wagons was erected outside the Catherine Wheel (on the site of the demolished Hart Street row) in 1766, designed by the town's Congregationalist minister Humphrey Gainsborough, who was a noted engineer. It was replaced in 1779, though its successor was only finally removed in 1872, when the pit was filled in. (fn. 115)

More extensive changes followed the 1781 Bridge Act, which established a body of bridge commissioners (including the corporation) with power to raise tolls. (fn. 116) The bridge itself, with an elegant five-arch span, was completed in 1786, abutting the north side of its patched-up timber predecessor. (fn. 117) Its realignment and wide curved entrances forced the demolition of several buildings adjoining its west end, among them the White Horse and another pub; the Angel, to its south, was retained and remodelled, with a new pathway leading down to it. (fn. 118) Such demolitions formed part of a wider scheme to remove obstructions and create 'commodious avenues' to the bridge. Hart Street was widened by the taking in of part of the churchyard, possibly precipitating the rebuilding of the church's south side in 1789, (fn. 119) and in 1794–6 the Middle Row west of the crossroads (including the shambles, the guildhall and the Plume of Feathers pub) was demolished. The new town hall was completed in 1796, built on the site of the demolished market house at the market place's western end. (fn. 120) Similar street improvements continued into the early 19th century, helped by an Act of 1808 which allowed further borrowing using the bridge tolls as security. Amongst other provisions it allowed for rounding of street corners at the crossroads and elsewhere, a scheme considered in 1796, but apparently not carried out. (fn. 121) Road widening on Hart Street was completed in 1829–30 by demolition of the Longland almshouses at its south-east end and their rebuilding on the west side of the churchyard, a proposal first made by the Dorchester turnpike commissioners in 1766; (fn. 122) the 17th-century almshouses on the churchyard's east side were rebuilt in 1846. (fn. 123) Private rebuilding of houses and major inns further transformed the town. The Bell and neighbouring cottages were rebuilt with fashionable stuccoed fronts in the late 18th century, transforming the town's northern approaches, while the prominent Red Lion was rebuilt and extended in stages from the 1730s to 1780s. (fn. 124)

10. Henley bridge and part of Jennings' wharf (south of Friday Street) c. 1793, looking north. The bridge replaced a timber predecessor (plates 3–4) in 1786. The Red Lion is visible near the bridge's western end.

Paving and lighting proceeded under the auspices of a newly established paving commission, set up under the Bridge Act. A street-lighting contract was agreed in 1781, and paving of Hart Street and Bell Street (by the local mason William Slemaker) was underway by 1784. New lamps were installed on the bridge in 1785, and a new lamp-iron on the churchyard wall in 1786. (fn. 125) Even so, in 1808 parts of Hart, Bell and Duke Streets remained narrow, ill lit and out of repair, so that at night it was difficult for carriages to pass in safety. (fn. 126) In 1833 the paving commissioners contracted the newly formed Henley Gas and Coke Company to light the town, and by early 1834 'elegantly constructed' cast-iron lamps were being erected along the main streets and bridge. (fn. 127) Northfield End and some other outlying streets were unlit until 1864 or later, however, (fn. 128) and robberies in 1858 were blamed on inadequate gas lighting in Hart Street. (fn. 129)

Industrial Premises and Waterfront

Most maltings, brewhouses and craft workshops still stood on back plots, of which some were accessed by side passages. (fn. 130) Nearly forty malthouses have been identified for the period 1700–1850, most of them relatively small-scale, (fn. 131) though by the later 18th century a few were developing into larger concerns. One was the future Brakspears' Brewery on New Street, which in the early 18th century comprised, fairly typically, a malthouse and brewhouse behind a street-front house. The arrangement survived the brewery's expansion in the early 19th century, with buildings grouped around a rear yard and accessed from a gateway and passage alongside the rebuilt house (Fig. 28). (fn. 132) No brewery buildings fronted the street until an attached mineral-water factory was built in the 1880s or 1890s, (fn. 133) although the brewery's tall chimney already dominated the skyline (Fig. 23). Most other industrial sites (including rival breweries) were similarly small-scale and hidden, (fn. 134) among them a silk-weaving factory on the north side of Bell Lane (c. 1814–56), (fn. 135) and a forge opened north of Friday Street in the 1860s, on the site of a tanning yard. (fn. 136) The close intermixture of domestic and industrial premises created sanitary problems well into the 19th century. (fn. 137)

Commercial development of the waterfront continued. A storehouse and granary formed part of the Red Lion inn by the 1730s, (fn. 138) and c. 1785 Barrett March, the inn's occupier, built an adjoining range of granaries running parallel to the river, in part replacing bargemen's houses. Barges regularly unloaded along that stretch, as well as at the wharfs north of New Street and south of the bridge. Goods and tackle were laid out on the shore sometimes for several days, where they were guarded by a night watchman paid 6d. a night. (fn. 139) Here, too, improvements were promoted under the 1781 Bridge Act, prompting protracted legal disputes with Strickland Freeman of Fawley Court who, as lord, claimed manorial rights over the waterfront. New embankments were built either side of the bridge between New Street and Friday Street, partly to improve the roadways, which until then flooded frequently. The changes allegedly made the waterfront less convenient for barges, although such claims were made partly to bolster the corporation's case against Freeman, and bargemen continued to use the stretch. (fn. 140)

Thereafter the character of the riverfront changed little before the mid 19th century, despite the advent of summer rowing competitions from 1829, and establishment of Henley's annual regatta ten years later. Stands for such events were temporary constructions, confined mostly to the area around the bridge and Red Lion; otherwise the riverfront was still 'principally occupied by wharfs' in 1850. (fn. 141) By then, the wharf north of New Street included a substantial domestic house, along with a warehouse, carpenter's shop, the Ship pub, and the landing place. (fn. 142) Two wharfs south of Friday Street (still owned by the Stonors) included adjoining tanning and coal yards. (fn. 143)

Cottage Yards and Early Suburban Growth

Alongside these improvements, rising population led to denser settlement and (for the labouring poor) increased overcrowding, reflected in subdivision of houses, adaptation of non-domestic buildings, development of cottage rows, and creation of cottage yards behind the street fronts. By 1841 at least ten such yards lay off Gravel Hill and off West, Bell, Hart, and New Streets, together housing over fifty families in cramped and insanitary conditions. (fn. 144) Goff's Yard, behind Bell Street and the Market Place, was started probably by the carpenter William Goff, who sold it in 1810; by then it contained six cottages and a communal water pump, accessed through a narrow passage from Bell Street. (fn. 145) Later it figured prominently in reports on slum dwellings. (fn. 146) Cottages in Barlow's Yard (off High Street) were 'new built' in 1818, (fn. 147) and several other yards seem to have originated around the same time. Some were created in the back yards of inns: Red Cross Yard off New Street, for instance, contained eight brick-built cottages in 1826. (fn. 148)

Newly built working-class housing was appearing on West Street and Gravel Hill by the 1820s and 1830s, that at the top of West Street lying close to the parish workhouse built in 1790–1. (fn. 149) Southwards expansion along Greys Road, Greys Hill, and what became Church Street (all of them then in Rotherfield Greys parish) occurred around the same time, (fn. 150) accompanied in 1834 by the building of a town gasworks north of Greys Road. (fn. 151) A few houses in that area were small middle-class villas, but most comprised working-class cottages for which the new church of Holy Trinity was built in 1847–8. A nearby vicarage house was built around the same time, followed in 1850 by Holy Trinity school. (fn. 152) Further south, a scatter of cottages and market gardens known as Newtown was laid out around the junction of Reading Road and Harpsden Lane probably in the 1830s; more intensive development in that area was constrained by Rotherfield's uninclosed fields and meadows, however, and Newtown remained detached from Henley until the more intensive suburban growth of the 1890s. (fn. 153)

Expansion and Rebuilding c. 1850–1914

During the mid 19th century the collapse of coaching and the decline of the river trade, precipitated by the opening of the Great Western Railway, prompted a period of protracted economic difficulty for Henley, which slowed its incipient suburban growth. But from the 1860s, with the acquisition of a rail link (opened 1857) and the burgeoning success of the regatta, the town embarked on a period of sustained expansion and redevelopment, turning it by the First World War into a fashionable riverside resort, and into a desirable residence for the prosperous middle-classes and professional London commuters. (fn. 154) Suburban expansion began with new streets laid out on the town's western and southern edges, followed from the 1890s by unprecedented expansion southwards along Reading Road and the higher ground to its west. Larger detached villas began to appear slightly earlier on the Fair Mile and elsewhere, continuing a trend noted in the early 19th century. (fn. 155) The town centre was transformed by renewed commercial rebuilding and, from the 1870s, by systematic clearance or improvement of cottage yards and other slum dwellings, underpinned by belated provision of a municipal sewerage and water system. Additional changes included a major restoration of the parish church in 1853–4, and replacement of the town hall in 1899–1901. Rebuilding of the waterfront transformed its character, turning it from a largely commercial area of wharfs and warehouses to one dominated by boathouses, villas and an hotel.

Suburban Growth and the Waterfront

Early plans for a railway branch line placed the station near the market place. In the end it was built on open ground in Rotherfield Greys parish, a short distance from Friday Street and the town's southern edge. A gated access road (later Station Road) was created by the Great Western Railway, the large kink towards its east end originally accommodating the station turntable. In 1877 it was taken over by the corporation, and from the 1880s its north side was gradually built up with houses. (fn. 156)

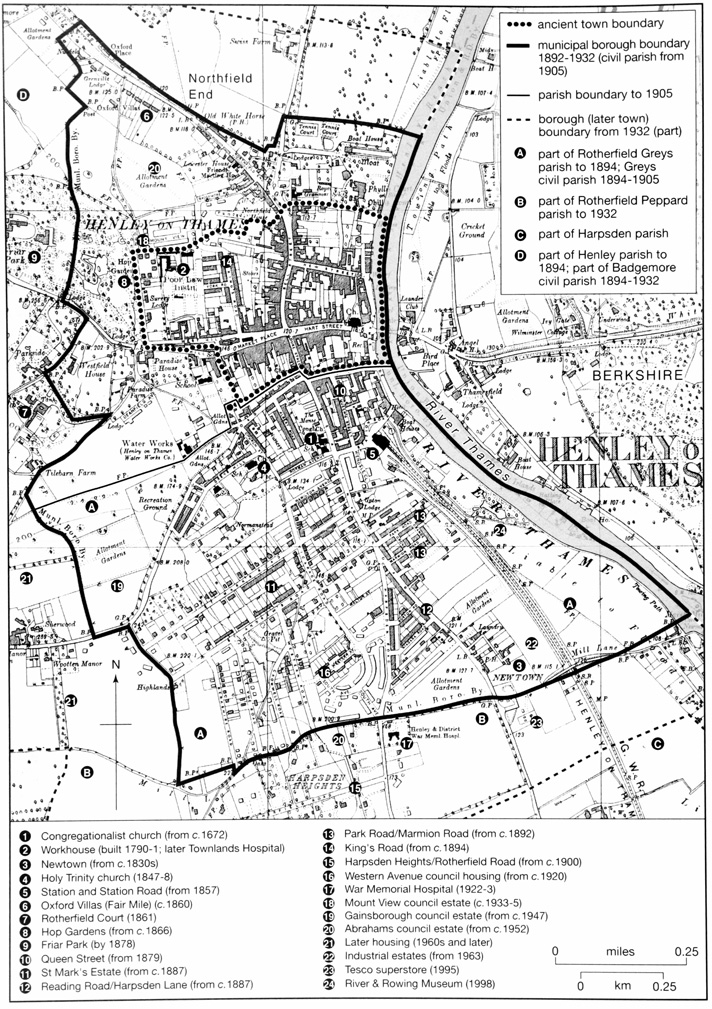

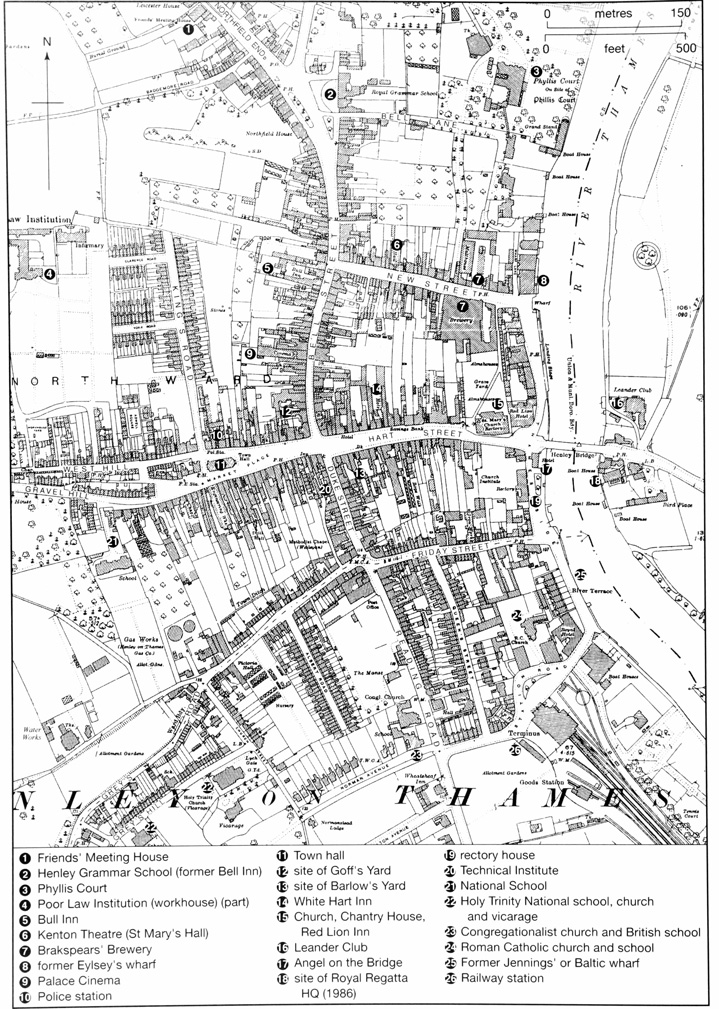

By then speculative local builders were laying out new streets around the town, which together marked a clear shift of gravity towards the station (Fig. 11). Even so land further south was not successfully developed until the late 1880s and 1890s, when the St Mark's Estate was built up west of Reading Road, and working-class terraces were erected along Reading and Harpsden Roads. (fn. 157) The latter connected Henley with the earlier cottages and market gardens at Newtown, which were brought into the municipal borough in 1892. (fn. 158) By the end of the century expansion seems to have been slowing: a projected road running parallel to Queen Street, for instance, was never begun. (fn. 159) Nonetheless building in 1906 was 'fairly brisk ... particularly in regard to superior residences', and Henley was said to be 'increasingly popular with city men, who find that week-ends in this favourite riverside town materially benefit them in health'. (fn. 160) Building of detached villas on the town's fringes continued, reflecting a need for 'houses of all kinds' reported in 1866; (fn. 161) among the most prominent was Friar Park, begun in the 1860s–70s and rebuilt on a grand scale c. 1889. (fn. 162) Two rather different outlying developments were a municipal cemetery at the far end of the Fair Mile, consecrated in 1868, and the nearby Smith Isolation Hospital, opened in 1892. (fn. 163)

Redevelopment of the waterfront (Figs 29 and 39) was underway by 1862, when the corporation used pauper labour to help build a continuation of Station Road along the riverside as far as Friday Street and the bridge. This crossed the Stonors' Greys and Baltic wharfs, then leased to the Henley builder Robert Owthwaite, and from 1866–9 the frontage there was built up with new riverside buildings including the Royal Hotel, Riverside Terrace, and (probably) the front part of Baltic Cottage. (fn. 164) The new riverside path, described as 'the direct way from the station', was paved and kerbed in 1865, and in 1873 the 'old wooden campshot' was repaired by the corporation. (fn. 165) Alterations north of the bridge came a little later, with conversion of the Red Lion granaries into boathouses and boat-building premises c. 1888, (fn. 166) replacement of the former Eylsey's wharf with boathouses and villas around the same time, and rebuilding of the Little White Hart pub c. 1900. (fn. 167) On the opposite bank, the first permanent regatta boathouse was built in 1864 above the bridge, followed by the Leander Club's first Henley clubhouse in 1895–6. (fn. 168)

Changes within the Town

Improvement of the town centre was achieved through a combination of private rebuilding and municipal initiative, reinforced by new local government powers and by the bylaws adopted from 1865. (fn. 169) Chief amongst the town's achievements was the gradual removal of the worst slum dwellings, and the belated provision in the 1880s of piped water and a modern sewerage system (described below). Improvements were also made to the central streets. Duke Street, still exceptionally narrow, was widened in 1872–3 by the rebuilding of its west side down to Greys Road, followed by further widening and rebuilding at the Greys Road crossroads in 1895–9. (fn. 170) Paving improvements in all the main streets were underway by 1864–5, when it was proposed to extend paving and surface drainage northwards up to Northfield End, and southwards to the area around Station Road. Street lighting was extended at the same time, and by January 1865 there were 82 public lamps, including 13 'recently erected' and 17 in the areas south of Friday Street and Greys Road. (fn. 171) Lighting and paving were regularly maintained thereafter, although in 1901 a hostile newspaper claimed that lighting and surface drainage remained poor, and that the paving stone used in Bell Street was easily crushed and turned to treacherous mud in the rain. (fn. 172) Tarmac was introduced incrementally from 1899, (fn. 173) and electric street lighting was considered the same year, although not adopted. (fn. 174) The central crossroads was enhanced in 1885 by an elaborate stone and marble drinking fountain given in memory of the rector Greville Phillimore (d. 1884), replacing the 18th-century obelisk, and in 1899–1901 the market place was transformed by the new and larger town hall. The drinking fountain was moved to the churchyard entrance in 1903, to be replaced by a tall iron lamp to light the crossroads. (fn. 175) Other signs of modernization included telegraph and telephone poles erected in the 1890s. (fn. 176)

11. Boundary extensions and main phases of suburban growth c. 1800–2000, superimposed on a map of 1938.

Despite these changes, Henley remained a working town with strong agricultural connections. The weekly corn market was well attended by local farmers, and a former mayor recalled seeing the whole of Hart Street, Market Place and Gravel Hill 'thickly occupied by cattle, sheep and horses exposed for sale'. (fn. 177) Behind the frontages there was considerable density of building. Many cottage yards continued into the 20th century (albeit much improved), and other back premises contained a variety of sheds, stores, stables, warehouses and workshops, divided by complex interlocking property boundaries. (fn. 178) Close intermingling of commercial and residential occupation caused sanitary problems which the local board struggled to alleviate. In 1871 there were complaints of smoke pollution from the Friday Street iron foundry and of 'offensive smells' from gas refuse, while livestock-keeping and slaughtering caused further difficulties. Cow yards on Friday Street prompted several complaints, and in 1878 a nearby printing works was 'surrounded ... on three sides by slaughterhouses, pigsties, cesspools and dung heaps', causing such a 'horrible stench' that the works risked closure. (fn. 179) Even so, some of the town's better streets retained open spaces. A house on Bell Street, occupied in 1901 by the estate agent Charles Simmons, had a garden of nearly an acre, with vinery, peach house, green house, summer house, and stabling. (fn. 180) Around the town's edges, allotments were laid out for the poor by the 1830s, and remained a feature of the town into the 20th century. (fn. 181)

The town centre's social geography remained much the same in 1901 as in 1851 (Table 2), (fn. 182) with Hart and Bell Streets (particularly the latter's northern end) among the smartest areas. At Northfield End the 'rising respectability of the property and owners' was one of the reasons given for improving its street lighting and paving in 1865. (fn. 183) By contrast, the unskilled labouring population remained concentrated along Gravel Hill and West Street, a polarization which was probably increased by partial clearance of cottage yards from the centre. The town's newer streets and suburbs similarly acquired their own social characters, which were reinforced by differential rents. (fn. 184) Further south, the old Newtown cottages (close to the newly built working-class terraces) remained among the town's poorest, and in 1901 an extended family of gypsies was encamped there with their caravans. (fn. 185)

Water Supply and Sewerage

Until the 1880s rainwater, domestic waste-water, and industrial run-off, sometimes contaminated with sewage, emptied into common drains which ran along the main streets and into the river. One of the drains was the ancient town ditch along Friday Street, which since the construction of an artesian well near the gas works c. 1845 was fed by a 'strong stream of pure water'. Nonetheless the constant flow of effluent directly into the river prompted complaints from the Thames Conservancy in 1867 and 1881, forcing the local board to install a deposit tank and filter beds at the ditch's Friday Street end. (fn. 186) In 1868 open drains on Bell Street were particularly 'unwholesome', and action was occasionally needed against owners who allowed their privies or WCs to discharge directly into the ditch or river. (fn. 187) Most houses still relied on cesspits, which were not always adequately sealed; in 1867 the board resolved to take action against anyone refusing to construct cesspits on their premises, and from 1880 it took on direct responsibility for emptying them. (fn. 188) Clearance was limited to the night hours, using properly covered carts and deodorizers; (fn. 189) even so, in 1882 a receptacle full of 'the most indescribable filth' was left outside a house in Greys Lane, while many parts of the town were so heavily built up that the contents of cesspits had to be carried through the houses. (fn. 190) Additional pollution of the river was caused by the numerous houseboats gathered there at regatta time and over the rest of the summer season. (fn. 191)

During the 1870s both the board and the town's ratepayers resisted pressure for a new sewerage system, asserting that enforcement of the bylaws, combined with a proper water supply, was the best solution. (fn. 192) In 1881, however, the builder (and board member) Robert Owthwaite complained to the Local Government Board in London that the Henley board was neglecting its responsibilities, and following an enquiry six months' notice was given for producing an alternative. (fn. 193) Further delays followed, partly because of difficulties in securing a suitable site, (fn. 194) but by 1886 sewage pipes were being laid through much of the town, (fn. 195) and an outfall works in Lambridge Wood opened in 1887. The scheme used Isaac Shone's Pneumatic System (already installed at the Houses of Parliament), by which compressed air propelled the sewage uphill from four ejector stations around the town. (fn. 196) The sewage plant proved inadequate, and in 1895–6 an additional outfall site was constructed between Lower and Middle Assendon, just over the parish boundary. (fn. 197) Further modifications were needed later, both to combat foul smells and occasional overflows, and to cope with the increasing volume of sewage. (fn. 198) Take-up of the new system was fairly swift. In 1888 the corporation ceased to empty cesspools, and by June 1890 1,024 houses had been connected, leaving only 38 outstanding. (fn. 199) Sewering of new suburbs and other areas brought into the borough followed during the 1890s. (fn. 200)

A few better houses (along with Owthwaite's Royal Hotel) had water supplied from rain- or springwater cisterns by the later 19th century, (fn. 201) but most still relied on wells. Before the new sewerage system these were at constant risk of pollution, particularly in the town's more crowded parts: a medical report in 1878 concluded that 'a more unsatisfactory and dangerous water supply for a town' could scarcely be conceived. (fn. 202) Nonetheless, most ratepayers considered the expense of building a municipal waterworks unjustified. (fn. 203) A private Henley Water Company was set up in 1880–1, which with the local board's cooperation constructed a 300,000-gallon reservoir on Badgemore Hill fed from a pumping station off Greys Lane, with a 240-foot well and two engines. (fn. 204) Two years after the waterworks' formal opening in 1882 some 156 houses had been connected, rising to 1,149 houses by 1891, (fn. 205) though in the 1890s some cottage yards still relied on standpipes or wells, and the system was not extended to Newtown until 1893. (fn. 206) A new main was laid along the top of the St Mark's Estate in 1909 following complaints about low water pressure in the higher parts of the town, (fn. 207) and c. 1912–13 a second reservoir was constructed at Mays Green in Harpsden. (fn. 208) Both reservoirs were replaced in 1988–9 by one at New Farm, Badgemore. (fn. 209)

Urban Development 1914–1960

Until the 1950s Henley's growth broadly continued the pattern established before the First World War, reflecting a similar continuity in its economic and social character. (fn. 210) In the centre and along the waterfront, its role as a fashionable shopping centre and seasonal resort led to development of new amenities, tempered by growing recognition of the need for conservation and careful planning. Continued pressure for sound, affordable working-class housing led to renewed suburban growth, dominated from the 1920s to early 1960s by provision of council housing. Slum clearance in the centre intensified in the 1930s, though with pockets of unsatisfactory housing surviving much later. (fn. 211)

Along the waterfront, the most significant change was the corporation's development from 1921 of recreational riverside gardens at Mill Meadows, south of Station Road. Further north, private leisure facilities were expanded at the exclusive Phyllis Court Club, opened in 1906 in the 19th-century Italianate mansion which replaced the earlier Phyllis Court. (fn. 212) The town centre saw relatively little new building, largely because so much had been replaced or remodelled before the First World War; (fn. 213) in addition, the economic case for preserving Henley's historic character and attractive setting was starting to be articulated. As early as 1898 plans for a railway extension to Marlow, involving a large viaduct over the Oxford–London road, were opposed on the grounds that it would detract from the 'superb scenery' which was 'the town's stock in trade', (fn. 214) and in 1933–4 plans for a modern cinema on Hart Street prompted strong local hostility. (fn. 215) A county-wide planning report in 1931 concluded that the town required 'special consideration on account of its popularity as a boating centre, the importance of its world-renowned regatta, and the beauty of the river and its surroundings', and that a 'carefully considered town-planning scheme is essential'. In particular the waterfront and Fair Mile were to be preserved from encroachment, and suburban expansion strictly controlled. (fn. 216) An incipient problem which planning could not completely avoid was motor traffic, which was causing concern by 1911. Car parking in Market Place was introduced in 1925, and bypasses, bridge-widening, and a second bridge were under discussion in 1929, although nothing was done. (fn. 217)

By then, provision of much-needed council housing was extending the town south-westwards (Fig. 11), beginning with low-density estates laid out on garden-city principles in the 1920s around Western Avenue. The Mount View estate followed in 1933–5 and the Gainsborough and Abrahams estates in the 1940s–50s, accompanied by renewed private building. (fn. 218) The fringe location of most council estates, combined with slum clearance in the centre, unintentionally reinforced social segregation, and by the 1960s the estates were being criticized for their isolation, monotony, standard chain-fencing, and lack of trees and landscaping. The town centre, too, was alleged to be approaching a 'planning crisis' fuelled by improved access to London and traffic congestion, in which the 'stock contemporary solution of the pedestrianized shopping street with service roads and parking off stage' would not work. Even so, critics acknowledged that growth had been contained and that the town still had clear 'entrances', while the centre retained some 'good urban design in the existing street pattern'. (fn. 219) New institutional buildings included the War Memorial Hospital (1922–3) on Harpsden Road, a new Roman Catholic church (1935–6) on Vicarage Road, and new almshouses (c. 1938) on Western Avenue, all of them in and around the new southern suburbs. (fn. 220)

12. Henley in 1925, showing key buildings.

Electricity was available from 1926, following a petition by fifty inhabitants in 1919, and a successful proposal to the corporation in 1922 by the Thames Valley Electrical Supply Company, which built a substation on Reading Road. (fn. 221) Take-up was relatively slow: street-lighting was by gas until 1930, (fn. 222) and no electricity was provided in pre-War council housing. In 1939 council house occupants took up an offer by the Wessex Electric Light Company for free installation of electric points, and in 1946 tenants on the Mount View estate applied to the corporation for the installation of electric lighting. (fn. 223) Improvements to the Lambridge Wood sewage works were needed by 1919, (fn. 224) and in 1932–3 the Assendon works were rebuilt; (fn. 225) following further problems, a new sewage plant was built to the north of the town off Marlow Road in 1955–7, and the Lambridge and Assendon plants were decommissioned. (fn. 226) The sewage system was extended along the Fair Mile and Greys Road in 1934–5, but Harpsden and Rotherfield Roads were excluded, and in 1947 over 100 houses in the expanded borough still relied on cesspools and septic tanks. By 1956 the number was 65, mostly near the southern perimeter in Mill Lane, Rotherfield Road, and Harpsden Way. (fn. 227) From 1960 the system was extended further, with new pumping stations opened at Deanfield in 1961 and in Park Road in 1966. (fn. 228) Corporation refuse was disposed of during the 1930s–40s in pits along the Fair Mile and at Lambridge, of which some caught fire; in 1940 one on the Fair Mile smouldered for several months. (fn. 229)

Keeping of poultry and livestock remained a feature of the town. In 1922 a Greys Road resident had 12 pigs, 90 chickens, and 20 ducks on his nearby allotment, and when new allotments were laid out at The Dean in 1945 (replacing others taken over for housing), they included pigsties. (fn. 230) Applications for pigsties and poultry sheds in back gardens continued in the late 1950s, some of them on recent council estates. (fn. 231)

Development Since 1960

From the 1960s creation of small industrial estates off Reading Road prompted some economic diversification, while the continued influx of new residents began to alter Henley's social tone. (fn. 232) Nonetheless its growth remained heavily constrained by planning considerations, in particular the need to balance economic viability and housing requirements with preservation of the town's historic character and visual appeal, both of which were seen as distinctive selling points and keys to future prosperity. Planning reports from the 1960s to 2010s consistently sought to reconcile these tensions, on the whole with some success. A study in 2009 found Henley a 'bustling' place with a 'compact town centre', attractive and varied buildings, plenty of local businesses, and an 'almost idyllic Middle England setting'. Even so, traffic, housing needs, pressure on local shops, and 'areas of ... hidden poverty' provided challenges for the future. (fn. 233)

Demand for affordable housing remained acute. Most building was in suburbs west of the town, though during the 1960s some of the larger suburban villas were demolished and their sites used for private housing. Upton Close replaced Upton Lodge (c. 1961–3), Leicester Close Leicester House (c. 1965–7), and Milton Close Paradise House (c. 1962–5). (fn. 234) By 1963 some 566 houses were under construction, with a further 649 planned. (fn. 235) Large-scale building continued into the 1970s, much of it to the west around Valley and Deanfield Roads, but with some encroachment on the southernmost parts of the Fair Mile. (fn. 236) Low-cost housing for small families remained in short supply in the 1980s–90s, and in 1985–6 the council allowed building of mixed housing on Deanfield allotments. (fn. 237) A residential caravan park at Swiss Farm was opened in 1961, and by 1979 made a significant contribution to housing needs. (fn. 238) Plans for 30 flats and 54 houses near Watermans Road were approved in 1999, creating Lawson Road, and the War Memorial Hospital and a few outlying pubs were also turned into housing. (fn. 239) By 1993 there were concerns that some of the expanding residential areas had insufficient recreational space, although provision as a whole exceeded requirements, with a variety of sports grounds and extensive riverside access. (fn. 240) New primary schools were built in 1970 and 1978. (fn. 241)

13. Henley in 1986, looking north-east. The triangle between Harpsden Road and Reading Road is part of the late Victorian and Edwardian suburbs. Industrial estates developed from the 1960s are on the right (towards the railway line and river).

Development of light industrial estates between Reading Road and the railway line began in 1963 with premises at Newtown Farm. Over the next 25 years private developers gradually extended the area up to Quebec Road. (fn. 242) More intensive industrial development was thought neither feasible nor desirable, and in 1993 the only other site earmarked for industrial or commercial use was the former Smith Isolation Hospital at the far end of the Fair Mile. (fn. 243) Land south of the Reading Road industrial estates (beyond Mill Lane) was sold by the town council in 1993 for a Tesco supermarket, prompting controversy because of the impact on town-centre shops and because the area was a sports ground. The store opened in 1995. (fn. 244)

The historic town centre was included in a new conservation area in 1967, theoretically giving greater protection following some controversial proposals in the early 1960s. (fn. 245) Thereafter the most contentious town-centre development was the new Waitrose supermarket off Bell Street (completed in 1994), chiefly because it involved demolition of the 1930s Regal cinema. (fn. 246) The new complex (which included a replacement cinema) was sited mostly behind the street front, making good use of the backland between Bell Street and King's Road, but destroying any remnant of the ancient burgage plots. By then, residential use of vacant sites in the centre was also being encouraged, partly to ease the pressure on the surrounding countryside, and partly to keep the town centre alive. The Brakspears' Brewery buildings on New Street were adapted for commercial, residential and hotel use between the 1980s and early 2000s, (fn. 247) while in 2006 mews developments were planned north of Market Place and south of Hart Street, on the site of Barlow's Yard. (fn. 248) Town-centre planning was made more difficult by increasing traffic, which by 1969 was having a 'disastrous effect'. (fn. 249) The area in front of the town hall (renamed Falaise Square in 1974 in honour of Henley's twin town in Normandy) was partially pedestrianized in 2001, (fn. 250) creating a pleasant area of benches and pavement cafés, though Bell and Duke Streets in particular remained narrow and often heavily congested. The run-down area around the station was improved in 1993–4 by the building of Perpetual House for a local investment company, in the crescent formed by the original station turntable. (fn. 251)

Unsurprisingly, Henley's waterfront saw little new development. The corporation's riverside gardens at Mill Meadows were extended in 1968, (fn. 252) and exclusive houses called Boathouse Reach were built on a vacant area south of Station Road in 1990. (fn. 253) Those were followed in 1998 by the prestigious River & Rowing Museum, in a concealed, park-like setting just off Mill Meadows. The opposite bank, near the bridge, was transformed in 1986 by the building of the striking new Royal Regatta Headquarters. (fn. 254) Plans in 1979 for a riverside path from Wharfe Lane to Station Road, passing under the bridge, came to nothing. (fn. 255)