A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Historic Parishes - Ashton Keynes', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18, ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/109-140 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Historic Parishes - Ashton Keynes', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Edited by Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/109-140.

"Historic Parishes - Ashton Keynes". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/109-140.

In this section

ASHTON KEYNES

ASHTON KEYNES village stands 8 km. south of Cirencester (Glos.), 5.5 km. west of Cricklade, and 14 km. north-west of the centre of Swindon. (fn. 1) The affix Keynes, the surname of the family which held the Rectory estate in the later 13th century, (fn. 2) is first recorded in 1490. (fn. 3) The parish is flat land drained by the upper Thames and is notable for the gravel extraction which has taken place there since the Second World War; in 2010 more than half the surface of the parish consisted of water-filled pits, now part of the Cotswold Water Park, a tourist attraction.

In the Middle Ages both the parish and manor of Ashton Keynes included the land of Leigh. Churches existed at Ashton Keynes by the 12th century and at Leigh by the 13th, the latter a chapel of the former. In 1548, however, holdings of land worked from farmsteads at Leigh were severed from Ashton Keynes manor and held as the manor of Leigh, and from the 16th century or earlier Leigh church had its own wardens. (fn. 4) In 1884 Leigh became a separate civil parish. (fn. 5)

Some Leigh farmsteads included land in Ashton Keynes, (fn. 6) and the vestry of Ashton Keynes allowed the rates levied on this land to be paid to Leigh. In 1778, on the eve of inclosure, most of this land was evidently commonable, and it was replaced by c. 120 a. of allotments in the south-east corner of Ashton Keynes. But 16 a. of land paying rates to Leigh had been inclosed before 1778; this became part of Leigh parish and lay as four islands within Ashton Keynes parish. The 120 a. or so allotted in 1778 separated a 16-a. island of Ashton Keynes from the main parish. (fn. 7)

A similar intermingling of lands existed in the Middle Ages with the manor of Shorncote (Glos. from 1896) (fn. 8) Tithes and rates were paid to Shorncote on certain lands in Ashton Keynes which later became part of Shorncote parish. At inclosure, to rationalize holdings and compensate for the loss of commonable land, Shorncote owners were allotted land in the northwest corner of Ashton Keynes and this was transferred to the adjoining Shorncote parish. (fn. 9) East of Ashton Keynes village, 16 a. in two fields, evidently inclosed before 1778, remained as islands of Shorncote parish surrounded by Ashton Keynes. (fn. 10)

Until 1778 the men of Ashton Keynes shared common pastures with the men of Somerford Keynes and Minety, and in that year, as Ashton Keynes's southeast and north-west boundaries with Leigh and Shorncote were revised, its west boundary with Somerford Keynes and Minety was redefined. (fn. 11) From 1778 Ashton Keynes parish measured 2,799 a. (1,133 ha.). In or about 1884 all the islands of land were transferred to the parishes which surrounded them, and Ashton Keynes parish increased in area to 1,137 ha. (2,810 a.). (fn. 12) Of the 120 a. or so allotted in 1778 to those paying rates to Leigh, 34 a. was transferred from Leigh parish to Ashton Keynes in 1984, thus increasing Ashton Keynes parish to 1,151 ha. (2,844 a.). (fn. 13)

Boundaries

Much of Ashton Keynes's boundary followed watercourses. On the north-east, the long boundary with South Cerney (Glos.) followed a head stream of the Thames called Shire ditch and had been set by 999. (fn. 14) On the south-east the boundary with Leigh followed the Thames for c. 3 km.; (fn. 15) after the boundary revisions of 1778 and c. 1884 it followed it for c. 1.5 km. and was otherwise irregular. Most of the irregularities were removed by the boundary revision of 1984, from when the boundary with Leigh followed the Thames for c. 2 km. On the south the boundary with Leigh followed a tributary of the Thames, Swill brook, for c. 500 m. (fn. 16)

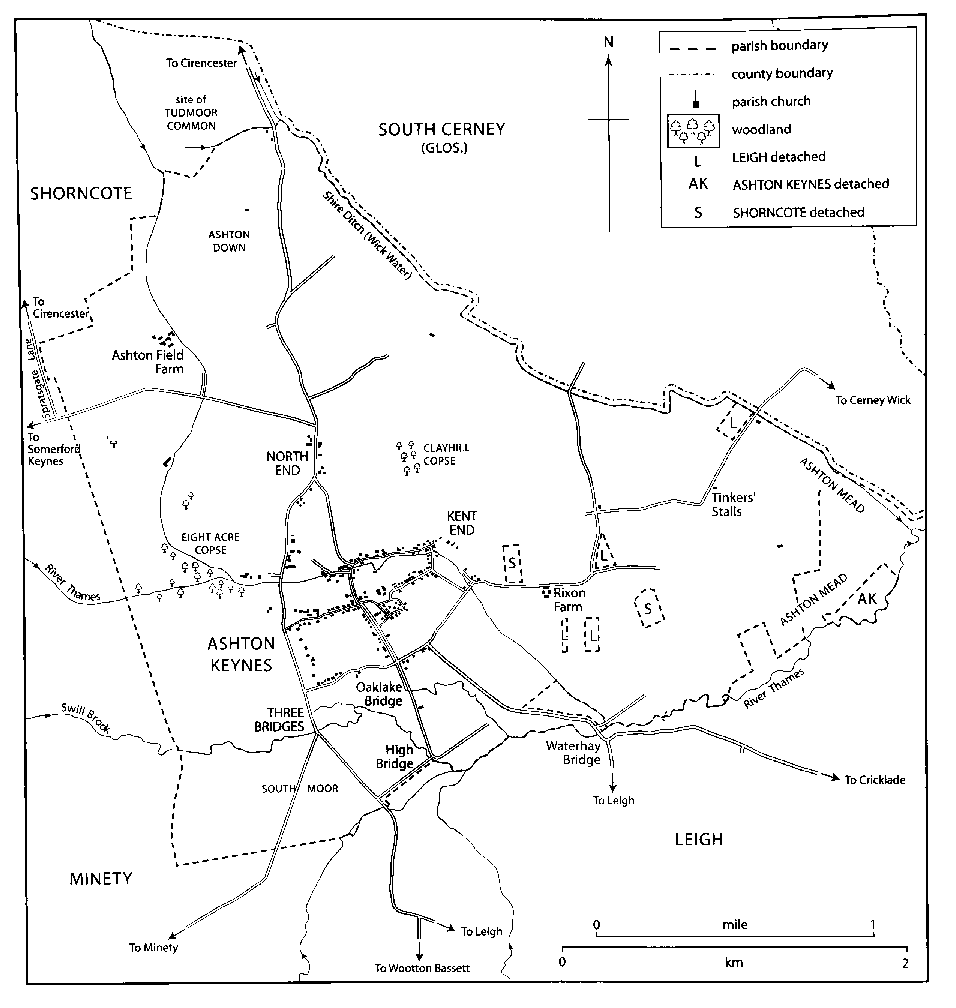

MAP 11. Ashton Keynes parish in 1875, showing detached parts of Shorncote (Glos.) and Leigh. More than half the surface of the parish now consists of water-filled pits left by intensive gravel extraction.

Although Ashton Keynes may have had a recognized boundary on the south-west with Minety and on the west with Somerford Keynes, (fn. 17) in both cases the boundary ran across common pasture shared with its neighbours and was redefined in 1778; (fn. 18) the new lines of the boundary are straight. Until 1778 the northern part of the boundary with Somerford Keynes followed a north–south road. A small section still followed the road after the boundary with Shorncote was revised in that year; the rest was diverted north-eastwards, became a boundary with Shorncote, and followed irregular field boundaries to a watercourse which runs into Shire ditch. A stone stood beside that watercourse to mark where Ashton Keynes, Shorncote, and Siddington (Glos.) met, and another, called Shire stone, stood beside Shire ditch where Ashton Keynes, South Cerney, and Siddington met. (fn. 19)

Landscape

The gravel quarried at Ashton Keynes had been deposited on clay by the Thames and its tributaries and head streams, and covered most of the parish. Near the watercourses alluvium overlies the gravel, and between two of the watercourses there are two low clay ridges. The land lies at c. 85 m., slopes gently downwards from west to east, and is almost flat. The two ridges rise in the west part of the parish: Ashton down, to the north, reaches 105 m., and the second, between Ashton down and the village, lies at a little above 90 m. The Thames enters the parish from the west at c. 86 m. and leaves the parish boundary on the east at c. 83 m. Swill brook, a southern tributary, crosses the parish, and there are two northern head streams: Shire ditch (otherwise called Wick water), which marks the parish boundary, and a watercourse along the west side of Ashton down. (fn. 20)

Ashton Keynes had large open fields and commonable pastures and, especially beside Shire ditch and the Thames east of its confluence with Swill brook, was rich in meadow land. Sheep-and-corn husbandry was practised in the parish, and cattle rearing and dairy farming were favoured by the extensive low-lying grassland. (fn. 21)

From c. 1960 much farmland north, east and west of Ashton Keynes village has been sacrificed to gravel extraction, and the resulting water-filled pits have been managed as lakes for recreation and wildlife. (fn. 22) In 2005 lakes covered most of the 1,022 ha. (2,525 a.) of Ashton Keynes and some were used for waterskiing and fishing. (fn. 23)

Communications

No major road has crossed the parish. West of Ashton Down, a north–south Romano-British trackway served the settlement there, and probably connected the area with Roman Corinium, later Cirencester. (fn. 24) The village was linked by radiating lanes to Cirencester, Cerney Wick (in South Cerney), Cricklade, Leigh, Minety, Somerford Keynes, and Shorncote before the inclosure of common lands in 1778, when the pattern was changed. (fn. 25)

The two oldest parts of Ashton Keynes village were linked to Cirencester by north–south lanes which converged at the north end of the village. The western branch may be the older and have been superseded by the eastern, called High road in 2005, which serves the more populous part of the village; as part of a Cirencester and Wootton Bassett road the eastern was turnpiked in 1810 and disturnpiked in 1864. (fn. 26) At inclosure in 1778 Gosditch, an east–west street in the village, was extended westwards to join the western branch, which was improved from that junction south to the crossing of Swill brook called Three Bridges; new straight roads were then made from Three Bridges south-eastwards to the Wootton Bassett road and southwards to the Ashton Keynes to Minety lane. (fn. 27) Since the late 20th century north–south through traffic has been directed to bypass the more populous parts of Ashton Keynes village by using the western branch of the old road, the improved road between the west end of Gosditch and Three Bridges, and the new southeasterly road from Three Bridges.

The lane which linked Ashton Keynes and Somerford Keynes may have run close to the house lived in by the lord of Ashton Keynes manor, north of which there lay a small park in the 18th century. (fn. 28) In 1778 it was replaced by a new road which, along two straight sections, linked Somerford Keynes to the Cirencester road at North End. The road which marked part of Ashton Keynes's boundary with Somerford Keynes, Spratsgate Lane, linked Cirencester and Minety, and from 1778 that road and the new Somerford Keynes road probably took the traffic between Ashton Keynes and Shorncote. (fn. 29)

At the south end of Ashton Keynes village the lanes from Cricklade and Minety ran across common pastures until inclosure in 1778, when they were set out mainly on new courses. The road from Cricklade, which crossed the Thames on Waterhay bridge, was evidently remade as three straight sections, including one running south-west to join High Road at the south end of the village; that from Minety was diverted to the new road running south from Three Bridges. East of Ashton Keynes village that part of the Cerney Wick road in which there were several right-angled corners may also have been set out on a new course in 1778. (fn. 30) Ashton Keynes and Leigh are linked by lanes which diverge from the Cricklade and Wootton Bassett roads.

To exclude lorries from most of Ashton Keynes village, to improve access to the gravel pits and to the country park, a new road, Spine Road (East), was opened in 1971. (fn. 31) It linked the London-Gloucester road in Latton parish to the Cirencester and Wootton Bassett road at North End. West of North End the Somerford Keynes road was improved (fn. 32) and given the name Spine Road (West), and to serve the gravel pits and a factory in the east corner of Ashton Keynes parish a new north–south road, given the name Fridays Ham Lane, was built along the course of an old lane between Spine Road (East) and the Cerney Wick road. (fn. 33)

Population

There were 207 poll-tax payers at Ashton Keynes in 1377, (fn. 34) and an adult population of c. 300 in 1676. (fn. 35) At the 1801 census the population numbered 764. It rose at each successive census until 1861, when it numbered 1,070; thereafter it fell at each census until 1921, when it numbered 744. It increased again as new houses were built in the village from the 1920s, to 774 by 1931, to 959 by 1951, (fn. 36) and to 987 by 1971. Between 1971 and 1991 the population rose by 42 per cent to 1,399, and in 2001 it stood at 1,420. (fn. 37)

SETTLEMENT

Early Settlement

Archaeological investigation in advance of gravel extraction has recovered widespread evidence of prehistoric and later farmsteads and settlements within the parish. West of Ashton Down, and lying partly in Shorncote (Glos.) a multi-period farm was occupied from the Early Bronze Age through the Iron Age and Romano-British periods. It was modified and reconstructed from c. 300 when new masonry-footed buildings and a large enclosing ditch were constructed; a further reordering took place probably in the 7th century with the building of post-built halls and sunken huts. (fn. 38) At Cleveland farm an extensive high-status Iron Age settlement, comparable in status with nearby oppida, continued into the Roman period, was reconstructed c. 300, and did not fall out of use until c. 500 or later. (fn. 39) Other Iron Age or Romano-British farmsteads have been discovered between Rixon Gate and Waterhay; south-east of Ashton Down; and at Ash Covert, on the boundary with Somerford Keynes. (fn. 40) Evidence for field systems, trackways, enclosures and the ring ditches of former barrows is scattered across the parish, and most such features, although undated, are of probable prehistoric or Roman date. (fn. 41) All are not necessarily contemporary, and considerable settlement shift, abandonment and reconstruction may have occurred here, as elsewhere in the fertile upper Thames valley, as a result of river-flooding, tribal allegiance, and the Roman administration. (fn. 42) Although few finds of later Anglo-Saxon date have been made, (fn. 43) the Domesday assessment of 36 tenant households (including Leigh) implies that the area of the later parish was well populated. (fn. 44)

Ashton Keynes Village

The medieval village had a complex polyfocal plan comprising at least four elements which have coalesced and have been extended to create the modern settlement. An early focus, indicated now by the position of the parish church, mill and Church Farm, lay close to the Thames crossing of an early north–south route. (fn. 45) There was already a water mill by 1086, (fn. 46) and this part of the village developed south of the site occupied by the church from the 12th century. The church may have been served at first by a rector, (fn. 47) and in the early Middle Ages the principal buildings of the Rectory estate probably stood on the site now occupied by Church farm, which later became the demesne farm of Ashton Keynes manor. (fn. 48)

A second, defensive, focus was created further east, in the area later known as Halls close. Here a moated ringwork, adjoining a sub-rectangular bailey and closes associated with it running south, has yielded tiles and pottery of early 12th–13th century date. (fn. 49) It may be the castle, described as at South Cerney (Glos.), which was captured by Stephen in 1139. (fn. 50) Its strategic importance must have declined thereafter, but it possibly continued in use as the demesne farmstead of the manor.

After Tewkesbury abbey (Glos.) acquired Ashton Keynes manor in c. 1102, (fn. 51) the abbey apparently replanned the settlement, which grew in the 12th century in two main parts. East of the present mill and along the north bank of the Thames, an east–west street lined with buildings developed, now Back Street and Church Walk, and this was intersected by an alternative north–south route, the present High Road. South west of the ringwork, the east–west lines of buildings along what is now Fore Street and Gosditch probably represent a more ambitious extension to the village plan. The effect of these developments, which may have included the digging of channels to bifurcate the river for water management, was to create a simple gridded street plan, perhaps with the unrealized intention of promoting a market where Gosditch broadens near its western end.

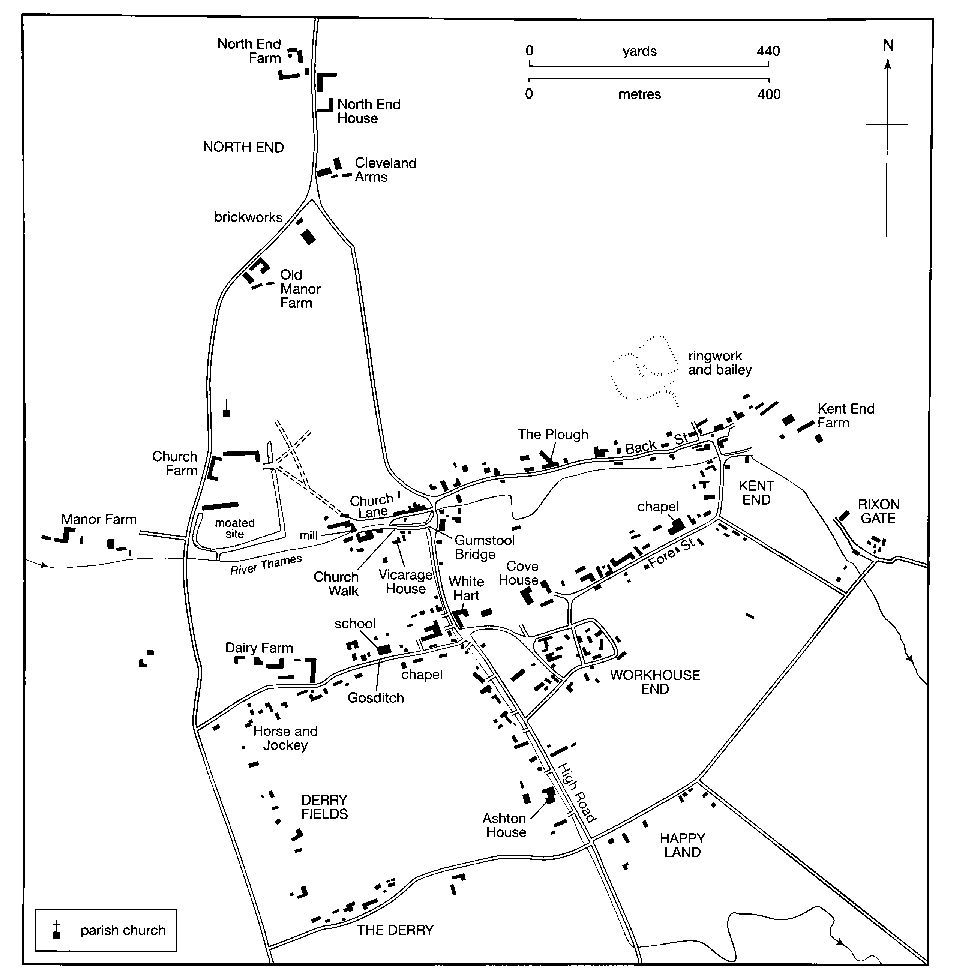

MAP 12. Ashton Keynes village in 1875. Settlement grew up around earthworks near Church farm and Kent End. Tewskesbury abbey re-planned the settlement along an east–west street, now Back Street and Church Walk, intersected by High Road. Fore Street and Gosditch probably represent an extension to the plan. Squatter settlements grew up on the outskirts.

Between the late 12th or early 13th century and the early 14th century a small manor, which was part of the Rectory estate, was held by members of the Sandford family and their descendants. The manor almost certainly included the buildings of Church Farm, standing on an unusually large rectangular moated site, which appears to have extended west of the present road, and by the 19th century was entered from the village. In the later 13th century the manor house was probably occupied by the Keynes family, which is remembered in the name of the parish. In the early 14th century Tewkesbury abbey, as the appropriator of Ashton Keynes church, proved its right to the small manor, (fn. 52) and by the 16th century the abbey had apparently merged the demesne of the small manor with the demesne of Ashton Keynes manor, of which it remained lord. Any buildings of the demesne farmstead of Ashton Keynes manor, which may have stood on the site of the ringwork, were abandoned and Church farm became the principal farmstead of the united demesne. In the 16th century the site of the ringwork was called Hall Close and was part of the demesne. (fn. 53) A large house was built as a manor house within a park north of the Thames near the church, probably c. 1714, and parts were converted to a farmhouse c. 1831. (fn. 54)

In the main part of the village the tenements held freely or customarily of Ashton Keynes manor evidently stood along the east–west streets. The village was populous, and the tenements were numerous; in 1604 there were c. 100 houses and cottages in the village. (fn. 55) The number of farms worked from buildings in the street almost certainly declined in the 17th and 18th centuries, (fn. 56) and in the 19th century and earlier 20th some of the houses were lived in by private residents and some, presumably incorporating workshops or shops, were used for trade or retail. (fn. 57) A new vicarage house was built in Church Walk in 1584. (fn. 58) In the 19th century a Nonconformist chapel and a school were built in Gosditch, a Nonconformist chapel and a manse were built in Fore Street, there were public houses in Gosditch and Back Lane, and small houses or cottages were built in all four parts of the east–west streets.

The earlier course of the Cirencester and Wootton Bassett road probably ran to the west of Ashton Keynes church and an eastern branch diverted from it to serve the village after its streets became lined with buildings, perhaps in the earlier 12th century. The eastern branch crossed both east–west streets and, because it was more used than the western branch, it became the main Cirencester and Wootton Bassett road until the late 20th century. Where it crossed the northern street, dividing it into Back Street and Church Walk, it was diverted eastwards to skirt the garden of the vicarage house built in 1584. In the 19th century an inn stood beside the main road near that junction, another inn stood where the road crossed the southern street, dividing it into Fore Street and Gosditch, and two smithies stood beside the road south of Fore Street and Gosditch. (fn. 59)

From the east end of Church Walk the Thames flows through the village in two courses, the first eastwards a little south of Back Street, and the second which became the main course, along the west side of High Road. The main course was altered as the village developed in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries: the river was channeled into a small canal and was bridged in many places, several large houses were built on the south side of Church Walk and the west side of High Road, and on the south side of Church Walk the vicarage house was largely rebuilt. Church Walk crosses the river on Gumstool bridge, which was rebuilt and lengthened in 1812. Also in 1812 a new bridge was made over the river in Church Walk (fn. 60) to improve pedestrian access between the church and the main part of the village; the footpath between the mill and the church was lined with trees by 1875. (fn. 61) The large houses on the west side of High Road, and some of their outbuildings, were approached by bridges across the canalized river; in the late 19th century there were four footbridges and eight bridges wide enough for a carriage or cart. South of Gosditch the road was apparently widened. In the later 19th century the house at the south end, Ashton House, had a small park on the east side of the road, and by then that part of the village had been gentrified. (fn. 62) The narrow bridge by which Gosditch crosses the river was rebuilt in 2005. (fn. 63)

Four crosses apparently stood in the south-east part of the village in the Middle Ages. One stands at each crossing of the east–west streets and the Cirencester road, and a third stands in Park Place off Fore Street. Each of those crosses is on a stepped base and is 14th- or 15th-century. (fn. 64) In 1812, when the bridges nearby were rebuilt, the cross at the Back Lane and Church Walk crossing was rebuilt on a site very near to its earlier one. (fn. 65) Blackwell cross, at the Fore Street and Gosditch crossing and so called in 1778, (fn. 66) was moved and restored in or soon after 1958. The fourth cross stands in the churchyard and was made in the late 19th century or early 20th from stones found in several buildings in the village and thought to have been parts of a former cross. The cross in the churchyard was rededicated as a war memorial in 1917. (fn. 67)

Buildings

The village buildings are typical of the

area. There is evidence of timber framing in the houses

built before the 17th century: three pairs of crucks in a

cottage at the west end of Back Street (fn. 68) are the only

medieval fabric known to have survived in the village.

The other oldest houses to survive were built very late

in the 16th century or in the early or mid 17th: they

include a house of one storey and a half with a central

chimney stack and now part of Dairy Farm in Gosditch,

a house on an L-plan adjoining the Grove in High

Road, a two-storeyed house now subsumed in Cove

House, and Mill House in Church Walk. Only Mill

House retains datable external features such as

mullioned windows. From the 17th century to the 19th

typical houses were built of coursed limestone rubble

with timber lintels. Roofs were covered with stone slates

or thatch. Little dressed stone was used and, until the

19th century, almost no brick. Even in the 19th century,

when they were made at North End, bricks were used

sparingly and mainly for chimney stacks.

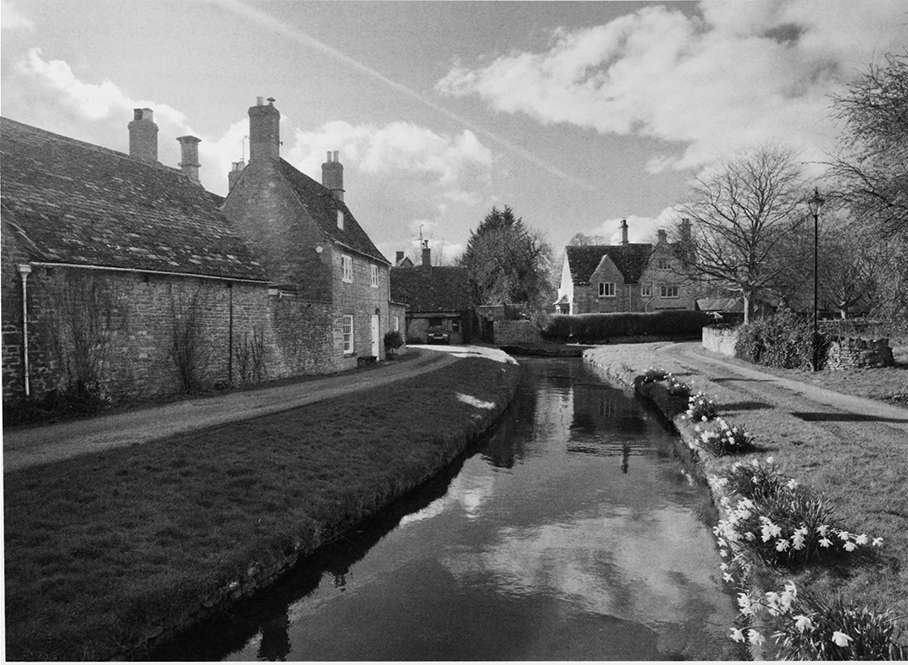

15. View of High Road looking north, showing the path of the Thames and the bridges across it to the houses on the west side.

The larger 18th-century houses in the village were built on what was apparently an established local pattern, with two storeys, attics, end stacks, and two or three rooms on each floor. Such houses include Brook House in Church Walk, Amcross Cottage in Fore Street, and, in High Road, the Long House, London House, and the Grove; the Grove has an outbuilding in which a 14th-century window has been reset. Cottages and smaller houses of the late 17th century or the 18th survive at Kent End, and a very small thatched cottage of one storey and attic survives at The Derry. Outside the village the larger houses built in the 18th century were of a standard local type. They include the farmhouses at Kent End farm, North End farm, and Rixon farm.

In the mid-late 19th century several villa-style houses were built in the village: they include Melton Lodge in Back Street (c. 1852–60), the manse (c. 1870s) in Fore Street, and Park House in Park Place which is notable for applied neo-classical detail. (fn. 69) Some 18th-century houses were altered to serve as inns and others were doubled in size, for example, a parallel range was added to a house in Gosditch and to Ashton Field farmhouse; a wing of new service rooms was added to Old Manor Farm; and Brook House was united to Brook Cottage by means of a linking range and given a detached coach house and stables.

Most 18th- and 19th-century buildings to survive are cottages of two storeys and of two or three bays. Those of the 19th century are taller, and of them the earlier ones are distinguished by stone voussoirs to segmental windows and the later ones by dressings or facades of ashlar. Many these cottages stand on sites apparently chosen at random. In some parts of the village dwellings may have been converted from outbuildings or workshops and in some cases one stands behind another. In the 20th century many private detached houses which replaced older buildings, or filled spaces between them, were built on a similar irregular pattern.

In the streets of the village, where the housing is largely undifferentiated, only a small proportion of the houses are of more than three bays. Some of the larger ones stand in High Road and there are others at the farmsteads on the periphery of the village. A number of buildings are of architectural interest, notably Cove House in Fore Street, Ashton House in High Road, the Congregational chapel and manse in Fore Street, and the 19th-century school in Gosditch. The village was designated a conservation area in 1974. The designated area was revised in 1994. (fn. 70)

Overall around 200 new houses were built in Ashton Keynes between c. 1920 and 2005, on new estates and on individual plots between older buildings. (fn. 71) There was also piecemeal conversion of non-domestic buildings to residential use. The houses built by Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council in the early 1920s and late 1930s at Kent End, were in cottage-style, and those built in the late 1920s were of concrete blocks. (fn. 72) The houses built at The Mead in the late 1940s were of the Airey type, and those built in the early 1950s were of concrete blocks. (fn. 73) In the later 1960s the council built houses and bungalows with stuccoed fronts in Harris Road. From the 1960s on many houses were built by private speculators and the later ones were built of simulated stone in simulated traditional style. Development took place in Eastfield, the Lotts, and Milling Close in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and in Ashfield and Harris Road in the early 1990s. In Richmond Court, the houses built in the 1970s are in Scandinavian style, hung with tiles, and have open front gardens. In the 1980s and 1990s many small detached houses were built on individual plots, mostly of blocks of simulated stone and some dressed with brick. Culde-sacs were built behind the main streets: The Leaze and Richmond Court off Back Street in the 1960s and 1970s; Thames View off Park Place in the 1960s and Birch Glade in the 1990s; and Sadlers Field off Fore Street in the 1990s.

South-east of the church

The church and adjacent

moated manorial site and mill are approached from the

village by lanes on either side of the river. Church Lane

is the path running along the north bank of the Thames

parallel to Church Walk. Thatched buildings stood

beside the path in 1810. (fn. 74) An 18th-century cottage

survived in 2005 and three houses and a pair of cottages

from the 19th- or early 20th-century. (fn. 75)

In Church Walk, a short street, three large houses stand on the south bank of the Thames: the old vicarage house, Brook House, and Brook Cottage. The mill house stands at the west end, and a former outbuilding has been converted into another house. Little survives of the 16th-century vicarage house: stabling dates from the 18th century, and the house was much altered then and later. (fn. 76) Brook House is an 18th-century double-pile two-storeyed house with a two-bayed main front, which originally had a central doorway. Brook Cottage is a late 17th-century two-storeyed house with casement windows and timber lintels. Brook House has early 19th-century stabling, and the converted outbuilding is of the 18th or 19th century and may have been the stables of Brook Cottage. The Mill House dates to the late 16th or 17th century. The house was built to a high standard, suggesting the miller was wealthy. Two gabled units project north, each with a large chimney stack and in the 19th century the house stood attached to a long west range and to the mill, which spanned the river to the south. Milling ceased in c. 1900 and the mill was demolished by 1913. Afterwards the house was restored, (fn. 77) and it was enlarged in 1933–4. (fn. 78) J. Merrit Poulton designed a new south wing to match the existing building, which almost doubled the domestic accommodation and included a drawing room and a library. (fn. 79)

Back Street

Most older buildings in the street have

been altered. Exceptions are the former Plough inn, a

large house bearing a date stone for 1694, and Melton

Lodge, a mid-19th-century house set back from the

street. The Plough, a gentry residence of five

symmetrical bays and two tall storeys, has attic rooms

lit by dormers in a hipped roof. The entrance is to the

east of a central chimney stack with back-to-back

flues, which emerge as a pair of chimneys. 19thcentury timber cross windows probably replaced

earlier ones of a similar type. A long range of stables

and outbuildings was built at the rear in the 19th

century. Pilgrim Cottage, at the east end of the street,

possibly originated in the 17th century as a small

farmhouse, was used as two cottages in the 19th

century, (fn. 80) and was a single house in 2005; by then what

were apparently farm buildings immediately east of it

had been converted for residence. Immediately west of

Pilgrim Cottage a house built in the early 19th century

with an attached industrial building had also been

converted for residence. At the west end of the street a

house on the north side is apparently 18th-century and

incorporates a mullioned window which may be

older, and a thatched cottage on the south side

incorporates crucks, and may be of the 15th or 16th

century. (fn. 81) In 2005 about half of the buildings in the

street were detached houses built in the 20th-century.

Fore Street

Only Cove House (fn. 82) and a few former

farmhouses survive. Amcross Cottage, which probably

originated as a farmhouse, and the Old Schoolhouse

both date to the 18th century. Most of the other houses

were built in the 19th and 20th centuries. (fn. 83) A shop and

a post office were open in Fore Street in 2005.

Gosditch

As in Fore Street, there is little evidence

in Gosditch of the farmsteads which almost certainly

lined the street in the 17th century and earlier. Only one

farmhouse survived: Dairy Farm at the west end of the

street was partly 17th-century and partly 19th-century.

The houses built from the later 17th century were

mostly small, detached, and standing in their own

gardens. On the south side of the street Lancresse

Cottage may be late 17th-century, and on the north side

Ivy Cottage is 18th-century. Some other houses date

from the 18th or 19th centuries. On the south side at the

west end of the street the Horse and Jockey, built in the

later 18th century, is unusual for the village as it is tall

and narrow and has a mansard roof. It was extended

westwards and doubled in size in the 19th century. Near

the east end of the street the Nonconformist chapel was

built on the south side in 1839–40, and on the north side

the school and schoolhouse was built in 1871.

Drummond Villas, a pair of houses in which

fashionable half-timbering is incorporated, was built a

little west of the school in 1904. (fn. 84) In the later 20th

century five houses were built on the south side of the

street and three on the north. About 1985 Dairy

Farmhouse was divided into two houses and the farm

buildings were replaced by 12 houses. (fn. 85)

High Road

In the 17th century or earlier High

Road developed as a residential area. Several large

houses stand on the west side with the Thames flowing

between them and the road, and most have large

outbuildings. They were probably built not as

farmhouses, (fn. 86) but for tradesmen or retailers. The Long

House, a former inn near Gumstool bridge, is of five

wide bays, two storeys and attics and has a stone-slated

roof. The northern end dates from the 17th century and

the southern end was rebuilt in the 19th century. (fn. 87) The

Grove, south of the junction with Gosditch, is of two

storeys and attics; it adjoins an L-plan house of the late

16th century or earlier 17th. The Grove and London

House were apparently built in the 18th century but

may have earlier origins. The Grove was used for

Baptist meetings in the late 19th century, and was

divided into two houses by 2005. London House on the

junction of Fore Street and Gosditch, is of four bays

with two storeys and attics. The premises belonged to a

succession of mercers: it may have been the 'shophouse'

of Anthony Ferris in 1604; by 1650 it was Richard

Marsh's shop, and became part of the Cove House

estate in 1667 when his widow married Oliffe

Richmond, who sold the house to John Saye, who

extended it to form Overbrook House by 1693; the shop

remained part of the Cove House estate and was a

mercery until c. 1750, and later a grocer's shop until it

closed in the 1970s. (fn. 88) The junction with Fore Street and

Gosditch, where one of the medieval crosses stood,

became a quasi village centre. Three other houses,

including the White Hart, were built there in the

decades around 1800, and a half-timbered village hall

was built nearby on High Road in 1914.

Ashton House stands at the south end of High Road on the west side of High Road. It was presumably built for a tanner as a complex of industrial buildings stood on the west bank beside it. (fn. 89) The site may have been chosen so that contaminated water flowed away from the village. In the late 18th or early 19th century, the house was given a classical five-bayed east front of two storeys with an attic lit by dormers, and inside a conventional plan with rooms arranged around a central staircase hall. In the mid 19th century the tannery was closed and the house became a gentleman's residence; by 1875 the house had been enlarged, new stables and outbuildings erected, and a 6-a. field on the east side of High Road laid out as a park. Two northern ranges were built parallel to High Road; the east incorporated part of the tannery building, and the west was a large service range. (fn. 90) In 1911 the south-west corner of the house was rebuilt in Jacobean style to provide a hall with a boudoir and a bathroom above it, (fn. 91) and in 1933, to designs by A. P. Dowglass of Cirencester, a new entrance block was built at the south-east corner. (fn. 92) A four-arched bridge to the house apparently survives from the 18th century and a two-arched bridge from the 19th century. (fn. 93) In the 20th century outbuildings of Ashton House and the Grove were converted for residence and smaller private houses were built on individual plots along both sides of the road; in the mid 1960s the stables south of Ashton House were converted for residence by the addition of a second storey; the new work was of brick and designed by Roderick Gradidge. (fn. 94)

Outlying Settlement

By the 19th century seven pockets of settlement had grown up on the edges of Ashton Keynes village, two of which were centred on large farmsteads. Although squatters apparently built most of the houses and cottages, they were generally of higher quality than those found in squatter settlements elsewhere.

North End

The name of the settlement beside the

Cirencester road by 1773, it apparently consisted of

North End farm, North End House, and a building

used as an inn in the 19th century. (fn. 95) The farmhouse at

North End farm was built in the 18th century and given

a west wing in the 19th; in the 19th and 20th centuries

there were farm buildings on both sides of the

Cirencester road. (fn. 96) North End House was built on the

east side of the road, apparently before 1773 and later

extended. (fn. 97) It is symmetrical, of three bays, and two

storeys, and built of squared limestone rubble with

ashlar dressings. A building on the east side of the road,

apparently built in the 18th century as a house and

attached cottage, was altered in or before the 1820s

when it became the New Inn: its four northernmost

bays were given wide sash windows, a rear staircase

tower, and flanking outshuts in brick, and a brewhouse

or bakehouse was built at the south end. One of the

outbuildings may have been built as a barn in the 17th

century. (fn. 98)

At the junction of the two branches of the Cirencester road there was a brickworks in the 19th century, in the mid 20th century a small telephone exchange and wooden and corrugated iron factory buildings were erected, and in the 1970s a small industrial estate was built on the site of the brickworks. (fn. 99) Only two new houses were built at North End in the 20th century. By 2005 an outbuilding at North End Farm had been converted for residence; the other buildings, 19th- and 20th-century, were only partially used.

Kent End

Growing east of Back Street, possibly

named after a family of tenants c. 1327, (fn. 100) it included a

pottery before 1650. (fn. 101) A farmstead stood there by c. 1700. (fn. 102)

The farmhouse was apparently built in the late 18th

century, and a large stone barn may be contemporary.

The other outbuildings which survived in 2005 were

20th-century and largely disused. West of Kent End

Farm several houses were built beside a path running

east as an extension of Back Street, and several more

beside a lane linking the east ends of Back Street and

Fore Street. Beside the path stood a house of c. 1700, a

larger 18th-century house, and a much altered 19thcentury cottage; beside the lane stood a cottage,

probably of 17th-century origin, and two other much

altered buildings, one which may have originated as a

pair of 18th-century houses, and another as four 19thcentury cottages. (fn. 103) The other houses at Kent End were

built in the 19th and 20th centuries. Cricklade and

Wootton Bassett Rural District Council built eight

semi-detached houses in 1921, six more in 1929, four

more in 1938, (fn. 104) and four bungalows in 1963.

Workhouse End

Parish property there housed the

poor: in 1611 the vicar of Ashton Keynes claimed that

seven tenements were held of him at will. (fn. 105) The

tenements were probably those a little south of Fore

Street described in 1778 as the church houses, on the

road now called Park Place. (fn. 106) In the late 18th and early

19th centuries one of these was the parish workhouse, (fn. 107)

and in the early 20th century the area was called

Workhouse End. (fn. 108) A long building, Long House and

Long Cottage, was built in 1765, (fn. 109) and the building

immediately south of it, possibly the former

workhouse, (fn. 110) may also be 18th-century. By 1899 more

cottages and small houses had been built, (fn. 111) and a few

were demolished in the 20th century. On the outer side

of the road, one cottage may survive from the 18th

century, several small houses were built in the 19th

century, and a few houses were built in the 20th. Park

House, a villa-style house, was built in the early 19th

century. One of the medieval crosses stands at the west

junction of Park Place and Fore Street.

Rixon Gate

The name of the area south-east of Kent

End, it grew up in the 19th century. In 1899 a dozen or

so cottages or small houses stood near the entrance to

the common pasture called Rixon, (fn. 112) about half of

which, altered and extended, survived in 2005. One

small house was built in the 19th century in 17thcentury style. A new farmstead, Guest Farm, was built

nearby c. 1925, (fn. 113) and several houses were built in the

later 20th century. Nearly all the land between two

straight roads, called Kent end and Rixon Gate in 2005,

bounded by Fore Street to the north, was developed in

the 20th century. Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural

District Council built 14 houses at The Mead in 1948–9,

another four in 1952, and two bungalows in 1957. (fn. 114) In

the later 1960s it built nine houses and seven bungalows

in Harris Road. From the 1960s more houses were built

by private developers.

Happy Land

Growing up south of Ashton Keynes

village, on the south side of the Cricklade road, which

was set out in 1778, the settlement was called Happy

Land in the 19th century. In 1899 there were a dozen or

so cottages and small houses on plots, presumably

allotted in 1778, running south-east from the road, most

of which survived in 2005. (fn. 115) A house in the angle of the

Cricklade and Wootton Bassett roads is probably of the

late 18th century; the others are apparently 19thcentury. A terrace of small houses with continuous

slated porches was built c. 1925, (fn. 116) and three houses were

built in the later 20th century.

The Derry

The Derry settlement on the south-west

edge of the village in 1778. (fn. 117) It probably consisted of

squatters' cottages, which except for two 18th-century

cottages, one with thatch and one with a single storey

and attic, were replaced by larger 19th-century cottages

and houses. A dozen of these houses stood there in

2005, some having been altered and enlarged.

Derry Fields

The 20th-century name of a line of

buildings leading south from the Horse and Jockey in

Gosditch, it lies parallel to the western branch of the

Cirencester road. In the late 19th century and early 20th

there were two small farmsteads, (fn. 118) one of which had a

new house built in 1886, (fn. 119) and three pairs of cottages in

1899. (fn. 120) By 2005 most of the houses and cottages had been

altered and extended, and no building appeared older

than the 19th century. In the later 20th century several

houses were built between Derry Fields and the western

branch of the Cirencester road.

Other Settlements

Historic settlement outside the

village consists of farm buildings. East of the village

Rixon Farm was built in the 17th or 18th century on

land probably inclosed in the 1590s. It incorporates a

range of buildings of the 17th or 18th century and a

farmhouse of the late 18th century; (fn. 121) a pair of cottages

was built nearby in 1904. (fn. 122) North of the village Ashton

Field Farm (formerly Westham Farm), where a barn is

dated 1779, was built apparently soon after the

inclosure of 1778. A cowshed and stables are also of the

late 18th century; (fn. 123) a pair of cottages was built nearby

in the mid 19th century and a pair was built beside the

Somerford Keynes road between 1890 and 1899. (fn. 124) The

farm belonged to the Cotswold Bruderhof 1936–41: the

farm buildings were converted for other uses and

many new buildings were erected near them by the

Bruderhof and later institutions which occupied the

site. Smaller farmsteads outside the village came into

use in the 20th century. Beside the Cerney Wick road

each of Wheatley's Barn Farm, Cleveland Farm, and

Wickwater Farm stands on or near a site where there

was a barn in the 19th century. (fn. 125) South of the village

Wheatley's Farm is also a 20th-century farmstead on

the site of a barn of the 19th century or earlier, (fn. 126) and

beside the Cirencester road north of the village, where

a few cottages had been built by 1875, (fn. 127) farm buildings

called the Downs Farm were erected in the later 20th

century. (fn. 128)

MANORS AND OTHER ESTATES

Tewkesbury Abbey (Glos.) and its successors held an estate in Ashton Keynes which comprised almost the whole parish and its great tithes. In the mid 17th century this estate was broken up and portions descended as separate estates. In 1778 each portion which held the right to keep animals on common pasture was increased in area as the pastures were inclosed, and each was reduced as land was allotted to the vicar of Ashton Keynes to replace tithes. In the mid 16th century, there were six small freeholds, (fn. 129) and the sale of Church farm and individual copyholds in the mid 17th century apparently created many more. Four of the freeholds were united or reunited with Ashton Keynes manor in the 1770s; two became the nucleus of the Cove House estate; Church farm and others were added to the Cove House estate in the 18th and 19th centuries; and a few remained as separate estates in the early 20th century. (fn. 130) In the 19th century the Cove House estate, Westham farm (a rump of Ashton Keynes manor), and the vicar's glebe were the principal estates.

In the early 20th century the Cove House estate was sold in portions, and in the mid 20th century there were c. 12 individually owned large or medium-sized farms in the parish. In the later 20th century most of the land was bought by companies for gravel extraction.

ASHTON KEYNES MANOR

An estate called Ashton given by King Alfred (d. 899) to Ælfthryth, his youngest daughter, (fn. 131) has been identified as that later called Ashton Keynes, (fn. 132) which in 1066 was held by the abbey of Cranborne (Dorset). (fn. 133) In 1102 Cranborne became a cell of the newly founded abbey of Tewkesbury (Glos.), (fn. 134) to which its endowments, including the estate at Ashton Keynes, were transferred. Ashton Keynes manor included Leigh, and the demesne of the small manor which was part of the Rectory estate was evidently merged with it in the later Middle Ages. It belonged to Tewkesbury abbey until, in 1540, it passed to the Crown on the dissolution of the abbey. (fn. 135)

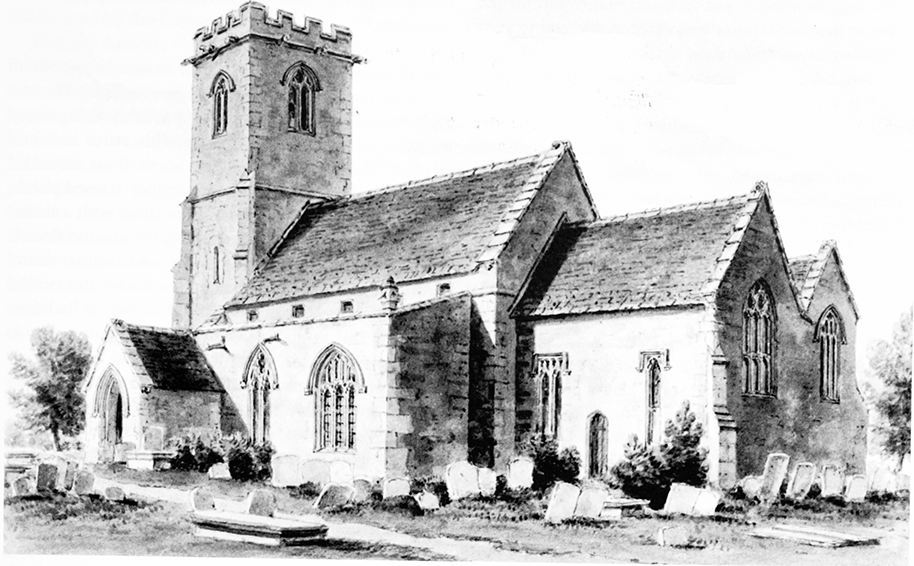

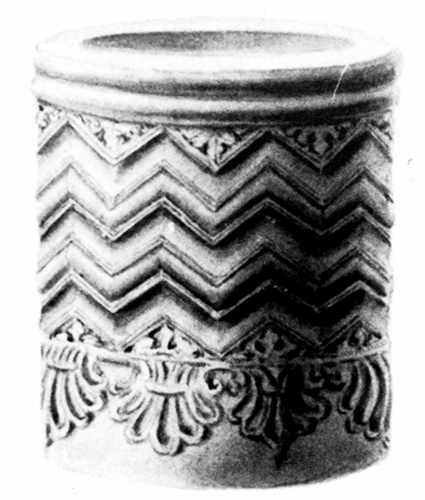

16. Manor Farm, gate piers at the entrance to the drive.

The Crown held Ashton Keynes manor until 1605; the land of Leigh was severed from it and sold in 1548. (fn. 136) A 98-year lease of the Ashton Keynes part of the manor granted in 1538 by Tewkesbury abbey to Sir Anthony Hungerford (fn. 137) was superseded by an 87-year lease granted in 1550 by the Crown to Sir Anthony (d. 1558); the new lease descended in the direct line with the manor of Down Ampney (Glos.) to Sir John Hungerford (d. 1582), Sir Anthony (d. 1589), and Sir John (d. 1635). (fn. 138) In 1605 the reversion was bought from the Crown by Sir Philip Herbert (earl of Montgomery from 1605), (fn. 139) who in 1612 sold it to Sir John Hungerford. (fn. 140) In 1623 Sir John sold the manor, and presumably surrendered the leases, to Sir Thomas Sackville, (fn. 141) who in 1632 sold the manor to George Evelyn (d. 1636). (fn. 142) The manor descended to George's son Sir John Evelyn (d. 1685), (fn. 143) who between the 1640s and the 1670s sold over half the manor, (fn. 144) including the part of the demesne later called Church farm. Most of the copyholds were sold individually. (fn. 145)

The reduced manor was devised by Sir John Evelyn to his daughter Elizabeth, widow of Robert Pierrepoint. Her heir was her son Evelyn Pierrepoint (marquess of Dorchester from 1706, duke of Kingston-upon-Hull from 1715), (fn. 146) who in 1714 sold the manor to Hawkins Chapman (d. 1768). (fn. 147) In 1770 the manor was settled on Henry Whorwood, a relative of Chapman's cousin Anne Chapman, who married Thomas Whorwood. By 1778 Henry Whorwood had increased the size of the manor by restoring or adding to it four estates. In 1772 he bought an estate sold by Sir John Evelyn to Henry Hawkins (d. 1658), of perhaps c. 100 a. from Evelyn's descendent Richard Hippisley Cox; (fn. 148) he also bought a larger estate, perhaps c. 150 a., from John Bristow, and two smaller ones, perhaps c. 30 a. and c. 15 a. respectively, from Samuel Teal and Somerset Wickes. (fn. 149) In 1779 Whorwood released the manor to trustees for sale, (fn. 150) and in 1781, after inclosure and the allotment of land to replace tithes, the estate covered c. 1,270 a.; (fn. 151) by 1785 it had been bought from the trustees by Henry's principal mortgagee John Paul. (fn. 152)

In 1781 the manor consisted mainly of four farms, Westham (later Ashton Field), Manor, Dairy, and North End. (fn. 153) Paul (d. 1787) devised it to his nephew Josiah Paul Tippetts (d. 1797), who took the surname Paul. Under John Paul's will the manor passed to Josiah's son John Paul Tippetts (later John Paul Paul) when the son reached the age of 24. (fn. 154) In 1796 North End farm, 311 a., was sold to Robert Nicholas, (fn. 155) and in 1808–9 John Paul Paul sold the lordship of the manor and Manor and Dairy farms, 509 a., to Nicholas. (fn. 156)

Manor House

The original demesne farmstead of

the manor was probably the moated ringwork known

as Halls Close. (fn. 157) A large house which stood on the north

bank of the Thames south-west of the church, may have

been built in the 18th century, perhaps soon after 1714,

the year in which a reduced Ashton Keynes manor was

bought by Hawkins Chapman, a member of a local

family. Until c. 1780 the house was lived in by the lord

of the manor (fn. 158) and was described as a mansion house. (fn. 159)

Gardens and 29 a. of parkland then lay north of the

house, (fn. 160) and a pair of earlier 18th-century gate piers

which stand beside the western branch of the

Cirencester road presumably mark where an east–west

drive from the house met the road. From the early 1780s

the house was not lived in by the owner, who in 1786

said it was too large to maintain from the income of the

estate and that part of it would be demolished. It fell

into disrepair and most of it was demolished between

1797 and 1802. In 1802 only a stable range and part of the

kitchen were said to remain. (fn. 161) In the 19th century the site

was redeveloped as a farmstead called Manor Farm: the

18th-century stone stable range, well-built with short

end wings and simple classical detail, was partly

converted; the northern wing, a carriage house, was

made into a barn, and buildings were added along the

west side; (fn. 162) new farm buildings were erected; and the

farmhouse was converted from the remains of the

mansion soon after 1831. (fn. 163)

The remains of the mansion house probably determined the size and plan of Manor farmhouse, which is an awkward L-shape with a large central chimney stack. The main block has two symmetrical piles of rooms of two storeys and attics, and a short south wing which has a hipped roof with a dormer. The east and west walls and part of the roof may be 18thcentury; the western side, which appears truncated, and the north wall were rebuilt with plain sash windows. In the 19th century a short brick east wing was added, and a long detached south-eastern range, (fn. 164) which had been demolished by 2005. In 2007 the stable range stood to the west of the dilapidated farmhouse.

Church Farm Estate

The estate later called Church farm was originally part of the rectory estate but by the 16th century had been merged in the main manorial estate and was probably the demesne farm. In 1655, when it was sold by Sir John Evelyn to Henry Hawkins (d. 1658) (fn. 165) it comprised c. 187 a. and the principal farm buildings. The estate seems to have descended to Henry's son John Hawkins (d. 1687) and have been settled on the marriage of John's daughter Joanna and Jasper Chapman. In 1738 the Chapmans' daughter Joanna and her husband Thomas Master (d. 1770) held the 187-a. farm, (fn. 166) and in 1787 their grandson Thomas Master sold it to Robert Nicholas. (fn. 167)

A second estate, perhaps 100 a. bought by Hawkins c. 1654, (fn. 168) probably also descended to his son John, and thereafter to John's daughter Elizabeth Cox and her descendants, (fn. 169) who sold it in 1772 to Henry Whorwood, lord of Ashton Keynes manor. (fn. 170)

Church farm descended as part of the Cove House estate, until 1913 when the farm, then 118 a., was bought by A. W. Bowley (fn. 171) (d. 1957). (fn. 172)

Church Farm buildings

By the 16th century the

demesne farm was focused upon Church Farm, on the

north-east corner of the moated site just south of the

parish church. The present house has two parts, both

possibly containing medieval fabric and arranged in an

L. A two-storeyed, south-eastern range of the mid-16th

century or slightly later is linked to a taller, mainly early

18th-century north-western range of four irregular bays

by a short return which combines fabric of both dates.

The south-eastern range has been much altered, but

details suggest that in the later 16th century, when the

manor belonged to the Hungerford family, it was part

of a fairly high-status dwelling. It was apparently a

chamber block in which heavy beams with vase stops

and unmoulded joists support an upper floor reached

by an inserted timber winder staircase. A four-light

timber mullioned window in the south wall, blocked by

the addition of an 18th-century extension connected

with farm use, lies adjacent to a small stone

chimneypiece ornamented with brackets and with a

lion rampant and the initials 'E R' in plasterwork on the

wall above. South-west of the house the farm buildings

include a barn which may be contemporary with the

north-western range of the house; they were converted to

dwellings in the late 20th century. Part of the manorial

demesne, including Church farm, was sold as a separate

estate in 1655 and perhaps then or later a farmstead, from

which the remaining demesne may have been worked,

was built north of the church. The farmstead was later

called successively Manor Farm and Old Manor Farm,

and a new farmhouse was built c. 1800. (fn. 173)

Westham (Ashton Field) Farm

Westham farm, 458 a. in 1890, (fn. 174) passed as a rump of Ashton Keynes manor from John Paul Paul (d. 1828) to his son Walter Matthews Paul (fn. 175) (d. 1861), who devised it to his wife Elizabeth. (fn. 176) The farm passed to their son A. G. Paul (d. 1912), who devised it to his wife Loetitia. (fn. 177) The farmstead, which was probably built in 1779, was called Ashton Field Farm by 1875. (fn. 178) The farmhouse, a standard type of four bays and two storeys, was doubled in size in the 19th century with the addition of a parallel range. In 1914 Loetitia Paul sold the farm to Hubert Cowley (d. 1916), in 1919 Cowley's executors sold it to William Haynes, and in 1920 Haynes sold it to Clements Cowley. By 1921 Clements Cowley had sold the farm in portions. The farmhouse and 201 a. were bought by Brig.-Gen. R. E. H. Dyer (d. 1927), 204 a. was bought by Giles Gobey (d. 1925), and 59 a. was bought by P. A. Read, the owner of Dairy farm. Ashton Field farm passed from Dyer to his widow Frances, who conveyed it to their son G. E. M. Dyer in 1930; in 1936 Dyer sold it to the Cotswold Bruderhof. In 1939 Gobey's land, called Ashton Downs farm, was sold by his surviving executor to the Bruderhof, which also owned Old Manor farm. (fn. 179)

COVE HOUSE ESTATE

A freehold estate in Ashton Keynes had emerged as a gentry residence c. 1700. It was probably held by Oliffe Richmond (d. 1691), and Bridget Richmond (d. 1701) who bought land there including Kent End farm. Bridget devised her estate to her son Oliffe Richmond, (fn. 180) probably the Oliffe Richmond who died in 1757. The younger Oliffe's heir was his son Oliffe (d. c. 1768, without issue), whose estate in Ashton Keynes covered c. 340 a. and was divided between his nephew Edward Nicholas and sisters Joanna (d. 1768 unmarried) and Jane (d. 1773 unmarried). Joanna's share was divided between Edward and Jane, (fn. 181) and in 1778 the whole estate was held by Edward's sons Robert and John, both minors. (fn. 182) Robert acquired John's share by exchange in 1785, (fn. 183) bought Church farm in 1787, North End farm in 1796, and the lordship of Ashton Keynes manor and Manor and Dairy farms in 1808–9. At his death in 1826 Robert Nicholas owned an estate of c. 1,400 a. based on Cove House, (fn. 184) later called the Cove House estate. (fn. 185)

Under an Act of 1827 the Cove House estate was vested in trustees, (fn. 186) and it was later sold pursuant to decrees in Chancery. About 900 a. was bought in 1846 by Harry Vane (from 1864 Harry Vane Powlett, duke of Cleveland), and 502 a. was bought by Vane in 1857. (fn. 187) The estate passed in 1891, on the duke's death, to his grandnephew Arthur Hay (from 1900 Arthur Hay-Drummond). In 1913 HayDrummond sold it to L. B. Woodford, who sold it in portions between then and 1917. (fn. 188)

Cove House

Situated on the north side of Fore

Street, it apparently originated as an L-plan twostoreyed house of the late 16th or early 17th century.

It became a gentry residence c. 1700 and was

extended to the south, after which four rooms on

each floor were arranged around a pair of central

chimney stacks. (fn. 189) Ashlar gate piers of the early 18th

century stand at the south entrance. Around the mid

1780s, Robert Nicholas (fn. 190) had the whole south range

encased to create a main block of five by five

irregular bays with an attic in the hipped roof; the

north range of the original house was adapted as a

service wing. Fore Street was diverted around an

allotment awarded to Robert Nicholas at inclosure

in 1778, which was laid out as a garden to the south

of the house by 1828. A walled kitchen garden and a

small park were laid out north of the house. (fn. 191)

Classical stables and a coach house were built east of

the house by 1831. (fn. 192) Around that time, the house was

given new sash windows and a top-lit staircase. In

1901–2 the house was again renovated and enlarged,

and additional stabling and accommodation for male

servants was built around a quadrangle east of it; (fn. 193) by

1920 a ballroom had been added at the south end of

the east front. (fn. 194) In the Second World War the house and

its park were requisitioned for use as a military camp,

and huts were erected in the park. For a few years after

the war the rural district council housed civilians in the

huts. (fn. 195) In 1950 the outbuildings were converted for

residence and Cove House became two dwellings. (fn. 196) To

the east of Cove House, an early 19th-century stone

farmhouse, with a large stone barn behind, belonged to

Cove House by the early 20th century, when it had been

enlarged and divided into cottages. (fn. 197)

RECTORY ESTATE

Ashton Keynes church was possibly among the endowments of Cranborne abbey (Dorset) transferred to Tewkesbury abbey (Glos.) in 1102; it was appropriated by either one of the abbeys and, like Ashton Keynes manor, was an endowment of Tewkesbury abbey until the Dissolution. (fn. 198) The rectory estate presumably at first consisted of all tithes from Ashton Keynes and Leigh and of a small manor. The rectory estate was presumably reduced when Tewkesbury abbey gave an estate of tithes to the vicar of Ashton Keynes. This had probably taken place by the later 13th century. In the 16th century the vicar paid a yearly pension of 4 marks to Tewkesbury abbey, in return for the revenues from this estate. (fn. 199)

An estate at Ashton Keynes, apparently a small manor, was held in the early 13th century by Thomas of Sandford (d. by 1242), who held the lordship of Chelworth (Cricklade). The estate at Ashton Keynes was held as dower by Thomas's widow Agnes, passed to his nephew and coheir Adam of Purton (d. c. 1265), who was said to hold it of Tewkesbury abbey, and passed to Adam's grandson and coheir Robert de Keynes (d. in or before 1281); Robert's heir was his son Robert, a minor. (fn. 200) In 1305–6 the small manor was disputed between Tewkesbury abbey, which claimed it as part of the Rectory estate, and Robert, who claimed it as a lay fee. The dispute was resolved in favour of the abbey. (fn. 201) By the 16th century the abbey had evidently merged the demesne of that manor with that of Ashton Keynes manor, of which it was lord.

In 1540, when Tewkesbury abbey was dissolved, the Rectory estate passed to the Crown, (fn. 202) and it descended with Ashton Keynes manor to Sir John Evelyn. (fn. 203) In the 1640s and 1650s Sir John apparently sold tithes with copyholds from which they arose, (fn. 204) and in 1672 he sold the remainder of the estate to John Hawkins (d. 1687). The reduced estate apparently consisted of a small holding, which may formerly have been a copyhold of the small manor, and of about half the great tithes of the parish. (fn. 205) It passed to Hawkins's daughter Mary (fl. 1719), the wife of Thomas Warner (d. 1736), and Thomas held it in 1705. After the death of Mary and Thomas it was held by trustees for the benefit of Francis Wyatt and Joanna Boughton, the younger children of their daughter Joanna Wyatt. (fn. 206) The trustees apparently sold the estate, which by 1777 had been bought from Benjamin Adamson of Bath by Henry Whorwood, the lord of Ashton Keynes manor. At inclosure in 1778 Whorwood received an allotment of 107 a. to replace his rectorial tithes from Ashton Keynes, an allotment of 8 a. to replace the commonable land of the small holding, and 14 a. at Ashton Keynes from the vicar in exchange for his rectorial tithes from Leigh. The 129 a. was added to Ashton Keynes manor. (fn. 207)

OTHER ESTATES

Bowley Estate

A. W. Bowley, the owner of Church

farm since 1913, (fn. 208) and of other land in Ashton Keynes,

bought Kent End farm, 166 a., and Rixon farm, 142 a. in

or soon after 1917, the same year that he purchased the

lordship of Leigh manor. (fn. 209) He sold both farms between

1924 and 1927, but by 1933 had acquired Wheatley's

farm, 36 a. (fn. 210) In the late 1930s Bowley sold Church farm

to one Lieberman, from whom he bought it back c. 1952.

The farms descended to his son A. W. Bowley (d. 1981)

and to his son Mr A. K. Bowley. In 2005 Mr Bowley

owned c. 200 a. in the parish, Church farm and

Wheatley's farm. (fn. 211)

Old Manor (formerly Manor) Farm

Formerly part of

Cove House estate, it was sold in 1914 to Mr Vizor. In

the 1920s it was acquired by M. J. Habgood, (fn. 212)

apparently the owner in 1934, (fn. 213) and in 1939 it was sold

by Francis Telling to the Cotswold Bruderhof, the

owner of Ashton Field farm. In 1941 the Bruderhof sold

the land of the farm to the London Police Court

Mission, (fn. 214) which in 1942 sold it to G. B. Young. Later in

the 1940s 14 a. of it was bought by A. W. Bowley, who

added that land to Church farm; then or c. 1950 the

remainder, from most of which gravel has since been

extracted, was bought by M. C. Cullimore or a

company controlled by him. In 2005 those lands

belonged to Mr. A. K. Bowley and Moreton C.

Cullimore (Gravels) Ltd. respectively. (fn. 215)

Manor (otherwise Coppice) Farm

Formerly part of

the Cove House estate, in 1913 it was sold to Sarah

Freeth, widow of Joseph Freeth. (fn. 216) By 1928, when it was

called Manor farm, it had passed to R. G. Freeth. (fn. 217) In

1969 Freeth sold it to Moreton C. Cullimore (Gravels)

Ltd., a company which afterwards owned it in 2005. (fn. 218)

Bruderhof Estate/Ashton Approved School

In 1941 the

Cotswold Bruderhof sold its estate of 494 a. acquired in

1939, consisting of Ashton Field farm, Ashton Downs

farm and Old Manor farm to the London Police Court

Mission, (fn. 219) a charity which used the buildings of Ashton

Field farm as an approved school and its land as a farm

on which the boys who lived at the school worked. The

management of the school was transferred to Wiltshire

County Council, which in 1973 bought the estate.

Before and after 1973 portions of the estate were sold,

mainly for gravel extraction, (fn. 220) and in 2005 the council

sold the buildings and the farm, 260 a., to the National

Children's Homes. (fn. 221)

Dairy Farm

Another portion of the Cove House

estate, 161 a., was sold in 1913 to P. A. Read, (fn. 222) who sold it

to Moreton C. Cullimore (Gravels) Ltd. in 1955, the

company which still owned the land in 2005. (fn. 223)

North End Farm

Acquired by Frederick Chamberlain

from L. B. Woodford, purchaser of the Cove House

estate, it covered 279 a. when purchased in 1917. (fn. 224) It

passed to Douglas Chamberlain (fn. 225) who, apparently in

the 1950s, sold most of it to E. H. Bradley & Sons Ltd.

for gravel extraction. (fn. 226)

Kent End Farm

A. B. Fletcher acquired the farm

between 1924 and 1927, presumably by purchase from

A. W. Bowley, (fn. 227) and owned it until, in the period

1965–71, he sold it in portions to Moreton C. Cullimore

(Gravels) Ltd.; the company owned it in 2005. (fn. 228)

Rixon Farm

Between 1920 and 1924, again

presumably by purchase from Bowley, Rixon farm

passed to Aubrey Seymour, (fn. 229) who owned it as a 237-a.

farm in 1929. (fn. 230) Seymour (d. 1967) (fn. 231) was succeeded by his

son Arthur, who sold most of the farm to E. H. Bradley

& Sons Ltd. and 18 a. to Moreton C. Cullimore

(Gravels) Ltd. (fn. 232)

E. H. Bradley & Sons

This gravel-working company,

operating in Swindon since c. 1900, (fn. 233) acquired North

End farm in the 1950s and most of Rixon farm, c. 1970.

Moreton C. Cullimore (Gravels)

The Stroud (Glos.)

haulage company, established c. 1927, (fn. 234) acquired for

gravel extraction Old Manor farm, c. 1950, Dairy farm

in 1955, Manor (Coppice) farm in 1969, and Kent End

farm 1965–71. It also acquired 18 a. of Rixon farm c. 1970.

The company still owned these properties in 2005.

ECONOMIC HISTORY

AGRICULTURE

In 1086 there were 15 ploughteams on the estate called Ashton, and enough cultivated land for one more. The lord's demesne land was worked by only two teams and five servi, and the tenants shared the other 13 teams. There were 20 households of villani, 12 of bordars, and four of coscets, or cottagers. There were 200 a. of meadow and ½ square league of pasture. (fn. 235) The estate almost certainly included the land which became Leigh parish and the farmsteads of some of the tenants stood on that land. (fn. 236)

Before Inclosure

Most of Ashton Keynes's agricultural land was used in common until 1778. Some of its common pastures lay open to common pastures of other villages and to the king's woodland in Braydon forest, and intercommoning took place. West of Ashton Keynes village a common pasture lay open to Somerford Keynes, and south-west of the village one called South moor lay open to Minety and probably to Leigh; (fn. 237) animals might pass and repass across the common pastures of Minety and Leigh between Ashton Keynes, Chelworth (in Cricklade), and the uninclosed land of Braydon forest south-west of Chelworth. (fn. 238) In 1256 the area of pasture shared by Ashton Keynes and Somerford Keynes was restricted or altered by an agreement between the lord of each manor, (fn. 239) and in 1387 the king's commissioners found that the men of Ashton Keynes might feed all their animals in Braydon forest except goats; pigs were excluded from the forest in the fence month and sheep were restricted to the lawns and excluded from the coverts. (fn. 240) North of Ashton Keynes village a 163-a. pasture called Tudmoor was shared by Shorncote, Siddington St Mary (Glos.), and Siddington St Peter (Glos.), and in the 17th and 18th centuries the men of Ashton Keynes also claimed the right to feed animals on part of it. (fn. 241)

In 1086 and throughout the Middle Ages a small proportion of Ashton Keynes's land apparently lay in demesne. (fn. 242) About 1210 the stock on the demesne of Ashton Keynes manor included 16 oxen, six cows, 150 sheep, and 27 pigs, (fn. 243) and in 1281 the demesne of the small manor which formed part of the Rectory estate included 102 a. of arable, 42 a. of meadow, and feeding for 16 oxen. (fn. 244) The two demesnes had apparently been merged by the 16th century and, c. 1550, besides the demesne nearly all of Ashton Keynes's land was shared by six free tenants of Ashton Keynes manor who held c. 150 a. and by c. 53 copyholders of the manor with tenements in Ashton Keynes. (fn. 245) A small proportion of the land was held by tenants of the manor with tenements in Leigh, (fn. 246) and 20 a. of meadow was part of Shorncote manor. (fn. 247) Both the demesne and the copyholds with tenements in Ashton Keynes consisted mainly of open-field arable, commonable meadow, and rights to feed animals in the common pastures. The demesne included a farmstead and c. 265 a., of which 152 a. was arable and 107 a. was meadow; 40 copyholders farmed c. 1,200 a. in holdings of between 83 a. and 6 a. and there were c. 13 cottagers. Typically the copyholds included twice or three times as much arable as meadow. (fn. 248)

Some of Ashton Keynes's commonable land was inclosed around the 1590s, this apparently included arable near the village, pasture called Rixon east of the village, meadow land near Waterhay bridge, probably in Leigh, and meadow on Ashton down north of the village. (fn. 249) On the eve of inclosure in 1778 Ashton Keynes had c. 2,130 a. of commonable land, 818 a. of open fields, 475 a. of commonable meadow, and 837 a. of common pasture. The arable lay in three fields, North, c. 317 a., East, c. 235 a., and West, c. 266 a., roughly north, northeast, and north-west of the village; the strips were small, the 168 a. belonging to Oliffe Richmond in the mid 18th century lying in 174 strips. The meadow, Ashton mead, lay east of the village beside the Thames and Shire ditch. The demesne plots in Ashton mead were evidently of 6–12 a. but most plots were smaller: Richmond held 21 plots totalling 39 a. in all. There were eight common pastures, all of which lay in the south-west part of the parish. The two largest were South moor, 341 a. south of Swill brook, and the Common, 285 a. apparently mainly west of the village. Home common, 117 a., Broadhurst, 36 a., Mare leaze, 24 a., and Startlets, 23 a., lay immediately south and south-east of the village; the other two common pastures were of no more than a few acres. (fn. 250)

In 1604 the demesne farm was of 332 a. and included Church farm, 75 a. in nine closes, 166 a. of open-field arable, and 91 a. of apparently commonable meadow; the closes included 32 a. inclosed about the 1590s, 20 a. of the down and 12 a. of Rixon. (fn. 251) In the mid 17th century it was apparently divided into holdings later called Church and Manor farms, and new buildings c. 200 m. north of the church may have been erected on Manor farm. In the early 18th century 187 a. was held with Church farm; it consisted of 40 a. in six closes, 100 a. of apparently open-field arable, and 47 a. of commonable meadow. (fn. 252) There remained many smaller farms with farmsteads in the village, probably still c. 40 in 1604. Of c. 55 copyholds there were 14 of between 30 a. and 60 a. assessed at 1 yardland, and nine of between 20 a. and 35 a. assessed at ½ yardland; the other copyholds were smaller. (fn. 253) In 1614 the vicar's glebe included farm buildings, 20 a. in closes, a nominal 75 a. in the open fields, and 6 a. of commonable meadow. (fn. 254) Outside the village Rixon Farm was built in the 17th or 18th century on land probably inclosed around the 1590s. The high proportion of meadow and lowland pasture in the parish favoured animal husbandry, and presumably the smaller farms could support flocks and herds larger than those on many farms of similar acreage elsewhere.

Inclosure

The animals of Ashton Keynes were excluded from Braydon forest without compensation when the Crown disafforested it in 1630. The men of Ashton Keynes were debarred from the right of common by the court of the Exchequer, which permitted the inclosure by decree, on the grounds that the land which they held had formerly been Crown land and that the right had not been part of Ashton Keynes manor when the Crown sold it in 1605. (fn. 255) Intercommoning by the men of Ashton Keynes was further restricted in 1767, when the common pasture of Leigh was inclosed, (fn. 256) and apparently ceased in 1780. The land of Ashton Keynes was inclosed under an Act of 1777 and in 1778 the commissioners allotted 147 a. of South moor to the men of Minety, who had shared that pasture until then, and set a boundary between Ashton Keynes and Somerford Keynes where common pastures had lain open to each other. (fn. 257) In 1780 the commissioners authorized the inclosure of 113 a. of Tudmoor, which they deemed to be the Siddingtons' proportion of it; the men of Ashton Keynes were excluded from that part, (fn. 258) and the remainder of the common was considered Shorncote's land. (fn. 259)

Common husbandry in Ashton Keynes ceased in 1778 when, under the Act of 1777, the open fields, common meadow, and common pastures were divided, allotted, and inclosed. Exchanges of land were made (fn. 260) and the larger farms became generally compact; (fn. 261) outside the village a second new farmstead, Westham (later Ashton Field) Farm, was built apparently soon after 1778. The vicar received land in place of tithes and, by exchange, a farmstead in Leigh, (fn. 262) and from the late 18th century most of the glebe was worked from Leigh as Glebe farm. (fn. 263) In the early 19th century there were eight principal farms: in 1831 Westham was of 417 a., Manor 240 a., Church 113 a., North End 265 a., Kent End 103 a., Rixon 391 a., Dairy 192 a., and Glebe c. 186 a. (fn. 264) Besides those of Westham, Rixon, and Glebe, each of which stood outside the village, all the farmsteads stood on the village's periphery. There apparently remained smaller farms based in the village. In 1778, 14 proprietors were awarded allotments of between 45 a. and 10 a., most of whom presumably owned small farms; (fn. 265) in 1831 Wheatley's farm was of 79 a., and there were farms of 62 a., 33 a., and less. (fn. 266)

Farms and Farming

Probably from the earlier 18th century to c. 1780 the lord of Ashton Keynes manor lived in the mansion house south-west of the church, and in 1781 the farmstead c. 200 m. north of the church apparently lacked a farmhouse. About 1800 a new house was built at that farmstead, which in 1831 was probably the principal one of Manor farm. (fn. 267) By 1856 Manor farm had been divided into two. Evidently soon after 1831 buildings on the site of the mansion house were converted for farming and a new farmhouse was built there, and in 1856 Coppice (later Manor) farm, 166 a., included that farmstead, and Manor (later Old Manor) farm, 130 a., included the farmstead north of the church. (fn. 268) By 1845 Rixon farm had been reduced to 236 a.; 106 a. of Ashton mead which had formerly been part of it was then a separate holding on which a cowhouse stood on the site of buildings later called Tinkers' stalls. (fn. 269)

The principal farms with over 100 a. in c. 1850 remained the same in the mid 20th century, (fn. 270) and throughout this period there was more grassland than arable. In 1845 the 457 a. of Rixon, Church, and Kent End farms included only c. 160 a. of arable, and all the 106 a. held with the cowhouse was then meadow; in 1856 the 331 a. of Manor and Dairy farms included only c. 100 a. of arable. Of the 818 a. of arable inclosed in 1778 most remained arable in the 19th century. North End farm included 187 a. of arable in 1845 and Coppice farm 113 a. in 1856; (fn. 271) Westham farm, a sheep-and-corn farm c. 1890, was of 458 a. including c. 300 a. of arable. (fn. 272) Westham farm was divided in three in 1921 and, as Ashton Field farm, was increased to c. 490 a. c. 1939. (fn. 273) Most of the other farms were mixed or dairy farms in the earlier 20th century, (fn. 274) and in the mid 1930s the arable, mainly north-west of the village, was much less extensive than the pasture. (fn. 275) Between 1936 and 1941 Ashton Field farm was used for mixed farming by the Cotswold Bruderhof. (fn. 276)

Besides the eight or nine principal farms, there remained small farms in the parish throughout the 19th century and in the earlier 20th. In 1895 there were 14 people described as farmers, (fn. 277) and in the 20th century small farmsteads developed outside the village. In 1910 Wheatley's farm was of 96 a. and included a farmyard south of Oaklake bridge and another between Kent End Farm and Tinkers' stalls, (fn. 278) and in 1910 and c. 1940 there were smaller farms and smallholdings with buildings at North End, Kent End, Rixon Gate, Happy Land, The Derry, and Derry Fields. Cattle, pigs, and poultry were kept on the smaller holdings. (fn. 279) Also in the later 19th and earlier 20th centuries there was c. 45 a. of orchards in the village. (fn. 280)

Large scale mechanized gravel extraction from farmland began c. 1944: the exhausted pits filled with water, which by 2005 covered much of the parish. From the 1940s to the 1960s Ashton Field farm was cultivated partly by the boys who lived at the approved school there. In the 1970s it was an arable and dairy farm of c. 300 a. and from the 1980s it was an arable and sheep farm of 260 a. (fn. 281) The only other farmland in 2005 was south of the village and immediately north of it. Church farm and Wheatley's farm were then worked together from the buildings south of Oaklake bridge and from Bridge Farm in Leigh (formerly Cricklade) parish; the composite farm was a 500-a. dairy farm of which c. 300 a. lay outside Ashton Keynes parish and on which as many as 250 cows were sometimes kept. (fn. 282)

WOODLAND

The place-name suggests that ash-wood was obtained or worked nearby in the late-Saxon period. (fn. 283) In 1086 there was woodland assessed at ½ square league on the estate called Ashton, (fn. 284) and in 1330 a wood belonged to the lord of Ashton Keynes manor. The manor included Leigh, and at both dates the woodland almost certainly stood at Leigh; unlike Leigh, Ashton Keynes never lay within the boundaries of Braydon forest, and in 1330 the wood was said to have been recently disafforested. (fn. 285)