An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 2, South east. Originally published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, 1970.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Introduction', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 2, South east(London, 1970), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol2/xxxv-xlii [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Introduction', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 2, South east(London, 1970), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol2/xxxv-xlii.

"Introduction". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 2, South east. (London, 1970), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol2/xxxv-xlii.

In this section

DORSET II

INTRODUCTION

Geographical Setting

The area described in the Inventory of S.E. Dorset covers just under 300 square miles. It extends from Weymouth eastward along the coast to Poole Harbour and N.E. as far as the river Stour; in the N.W. it includes Dorchester, the county town. It has little natural unity and the complex geological structure is reflected in the diversity of the countryside. Here may be found rolling downland, open heathland, clay vales and limestone tableland, which together with the exceptionally varied coastline form a landscape of outstanding beauty, as yet hardly spoilt by modern development.

The area covers a broad wedge-shaped basin with its apex to the W., almost all under 200 ft. above O. D. and bounded by hills rising to between 200 and 300 ft. on the N. but to over 600 ft. on the W. and S. The central basin is almost entirely heathland produced by the underlying Bagshot Beds and is drained by various streams, including the rivers Frome and Piddle, flowing E. to the almost enclosed Poole Harbour with its many bays and islands. The heathland is ringed by relatively narrow outcrops of London Clay and Reading Beds which produce a well-wooded landscape of no great relief but rising to 300 ft. in the N.E. around Lytchett Matravers. The rest of the N. part comprises the S. extremity of the Chalk dip-slope of the Dorset Downs and here is a fragment of typical Chalk downland country with broad valleys, rounded interfluves and dry combes, drained by the lower reaches of the North Winterborne and by the river Piddle. In the W. and S. parts of the area the Chalk is again the predominant underlying formation, but here complex geological structures have produced a different landscape. The S.W. is dominated by a massive ridge, the South Dorset Ridgeway, running roughly E. to W. and rising to over 700 ft. in the extreme W. on Black Down. The ridge extends S.E. to a broader and lower area of typical Chalk downland between Winfrith Newburgh and West Lulworth. S.W. of the Ridgeway, around Weymouth, is a small region of clay vales, running E. to W., set between low limestone and sandstone escarpments formed by the erosion of a huge anticline or fold in the underlying Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous rocks. The Isle of Portland forms the S. side of this fold and projects S. into the English Channel. Lastly, in the S.E., is the Isle of Purbeck, bisected from E. to W. by the hog's-back Chalk ridge of the Purbeck Hills which rise to over 600 ft. To the N. of this ridge is heathland forming part of the central basin. Immediately to the S. is the deep valley of the East and West Corfe rivers, cut in the underlying Wealden Beds, and beyond rises the high limestone tableland of the Purbeck and Portland formations. This extends to the sea, forming precipitous cliffs, except on the W. where the softer Kimmeridge Clay outcrops to form a semicircular area of generally lower land.

Rural Settlement Pattern

Prehistoric and Roman

Little can be said about settlement in S.E. Dorset before the Iron Age for hardly any direct evidence has survived. The existence of barrows (fn. 1) may indicate the proximity of settlements so far undiscovered, but their main concentration along the S. Dorset Ridgeway is more likely to reflect the importance of the Ridgeway as a route rather than the presence of any specially large population in the immediate area. The widespread scatter of barrows on the heathland, particularly the S. side, may however imply settlement there of greater density than in subsequent times.

Many earthworks of the Iron Age and Roman periods have been recognised, (fn. 2) largely on the high ground where there has been little or no subsequent ploughing to destroy them. The known distribution is thus the result of chance survival and accidental discovery and probably bears little relation to the original pattern. The inclusion of a large number of buried sites unassociated with earthworks gives a more balanced picture, particularly for the heathlands, though it broadly sustains the impression of an upland distribution. The high density of settlement in Portland and S. Purbeck, especially in the Roman period, is remarkable and probably reflects their importance as sources of raw materials.

Mediaeval

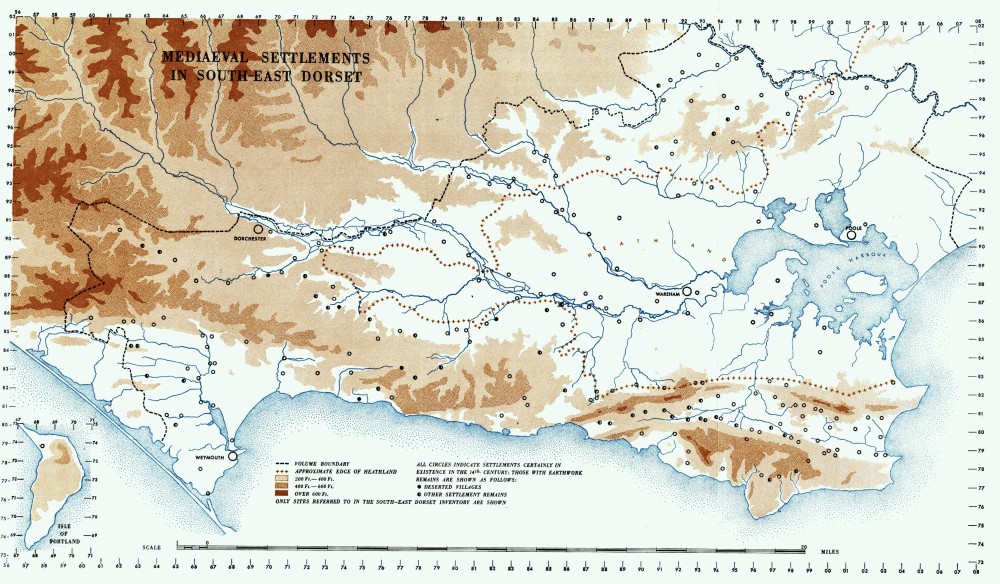

A reasonable picture of the settlement pattern can first be drawn for the mediaeval period (see Fig. opposite), but it is not complete, for some at least of the minor settlements not named in early documents were probably in existence long before their first appearance in any surviving record. On the whole the settlements were small; the large nucleated village is, even today, conspicuous by its rarity, and most of the settlements are still single farms and small hamlets no more populous than they were in the 14th century or earlier.

Distribution has been largely controlled by the natural environment. The heathland was mostly left empty except for small farms and hamlets along the courses of the major streams, with Wareham on the terrace between the rivers Piddle and Frome as the only place of any size. The edge of Poole Harbour proved attractive but here too all the settlements, with the sole exception of Poole itself, have until recently been very small. The few settlements within the heathland proper, such as Hethfelton in East Stoke and Claywell in Studland, have never been more than the single farms they are today. The land around the edge of the heathland, where the Reading Beds and London Clay provide a more fertile fringe between the Bagshot Beds and the Chalk, attracted extensive settlement. This is particularly well marked along the S. edge of the heathland and is repeated to the N. where there were many tiny settlements in isolated valleys in the rather broken countryside from Lytchett Matravers to Bloxworth.

The Chalk areas in the N. and W. show a settlement pattern typical of this kind of country, with lines of small settlements lying along the valley bottoms and often set close together. Such series of settlements occur along the lower reaches of the North Winterborne and the Milborne Brook and along the South Winterborne. In the Chalk land to the S. where there are only short, dry valleys the settlements tend to be more isolated. In the area of the folded Jurassic Beds N. and N.W. of Weymouth there is again a pattern of small settlements, here set in clay vales along the streams, particularly along the deeply cut valley of the river Wey. The S. half of the Isle of Purbeck, S. of the Purbeck Hills, has an exceptionally dense settlement pattern, but here again, until the modern development of Swanage and with the one exception of Corfe Castle, the area was one of small farms and tiny hamlets, almost all of which were already in existence by 1086.

Post-mediaeval

Mediaeval Settlements in South-East Dorset

The essentially small rural communities of the mediaeval period have continued with a few exceptions right up to the present century. Few of the villages and hamlets grew to any size; indeed many show evidence suggestive of contraction, which took place, if at all, in the post-mediaeval period (see p. lxviii). The relatively large number of isolated farmsteads of the 17th to the 19th centuries suggests a development from the earlier scattered settlement pattern. However, this is probably only partly correct, for there is little doubt that many of these farms were rebuilt on much older sites, though this can be proved but rarely.

Several small isolated settlements comprise two or three houses grouped round one farmyard. At Friar Waddon, Portesham (29) (Plate 147), this seems to result from the shrinkage of a hamlet where the three surviving old houses stood around a small green; but the original relationship between the houses at Shilvinghampton, Portesham (26, 27), Wilkswood, Langton Matravers (6), or the farm groups illustrated at Whiteway, Church Knowle (22) (Plate 51), and Lower Lewell, West Knighton (7) (Plate 50), has yet to be explained.

Towns

The pattern of small scattered rural settlements is reflected in the slow growth of towns. Until the 13th century only Dorchester, the Roman Durnovaria, and Wareham, a Saxon borough and a port, were urban centres; both were small and easily confined within their ancient walls. Poole and Weymouth developed into ports in the 13th century, the former superseding Wareham, but though both were granted charters neither figured among the main towns of mediaeval England, (fn. 3) and, though Poole's prosperity increased with the growth of the Newfoundland trade which reached a peak in the late 18th century, neither ever ranked among the main exporting and importing centres. (fn. 4) Lesser towns in the area were Bere Regis, made a free borough by Edward I, and Corfe Castle, which grew as a result of the Purbeck marble industry and received a charter in the 16th century; but neither of these is now more than a village; a third was Swanage, which became a small port for the handling of Purbeck stone.

As a whole the towns show little evidence of growth until the end of the 18th century. Weymouth was the first to develop when, largely as a result of royal patronage, it became a favourite resort. Dorchester, surrounded by the open fields of Fordington, did not expand until the latter were enclosed in the mid 19th century, when the arrival of the railway there and at Wareham encouraged building outside the old walls of both towns; Poole also began to spread beyond its mediaeval boundaries at about the same time.

The last hundred years, more particularly the last fifty, have seen a huge expansion of the urban areas to meet the needs of the tourist industry. Weymouth is now a large and prosperous seaside resort, and Poole, together with the adjacent Bournemouth, forms the largest non-industrial conurbation in the British Isles. Swanage too has developed, and many of the formerly small villages along the coast, such as Studland, West Lulworth and Osmington, are rapidly growing. Nevertheless, away from the coast, in spite of military training camps and the Atomic Energy Establishment on Winfrith Heath, the area still retains much of its rural nature and the settlements remain small. Wareham is still a small country town and Dorchester has changed its character but little.

Settlement Morphology

The small size of the rural settlements in the area makes it impossible to generalise about their layout. Because of the physical background, settlements of any size, especially in the narrow valleys of the Chalk country, tend to be elongated street villages. Elsewhere they rarely show any significant form and have largely irregular nucleated layouts. In the N. of the area, in the broken land on the Reading Beds and London Clay, the settlements have a notably scattered form, e.g. Bloxworth and Morden, probably resulting from slow piecemeal growth in a difficult environment.

The urban areas are even more diverse, as a result of differing physical settings and historical developments; these are discussed in the Inventory in the prefaces to the individual towns.

Land Units and Organisation

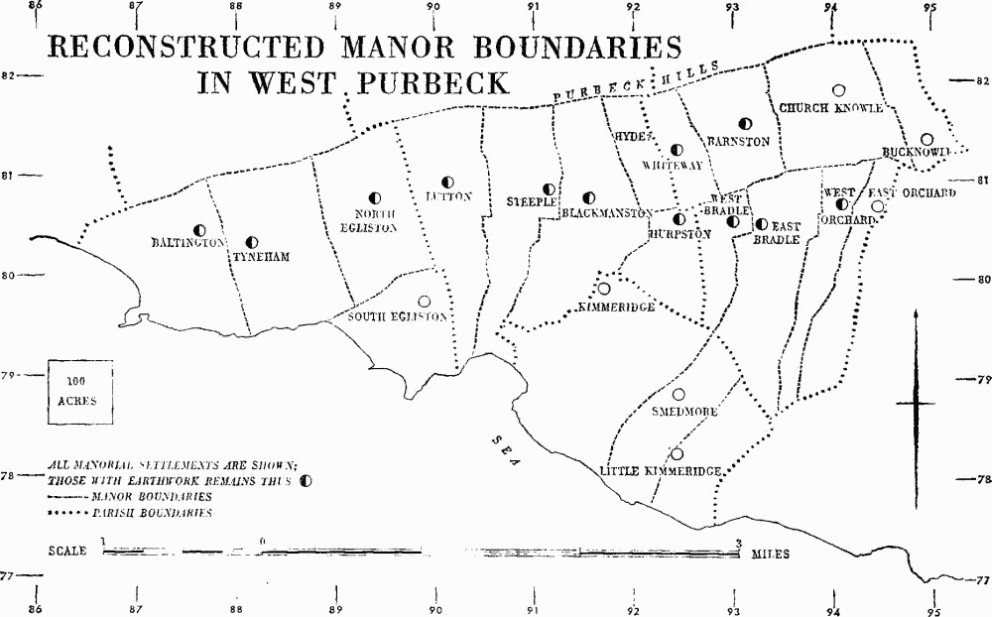

The Inventory which follows is based upon modern civil parishes, which, with certain notable exceptions, are the direct descendants of mediaeval ecclesiastical parishes. In an area of scattered small settlements, however, the mediaeval parishes were not usually the basic mediaeval economic units. Occasionally they were, as at Winterbourne Abbas and Bincombe, but the vast majority resulted from the ecclesiastical grouping together of a number of much older settlements and their associated lands. It is not always possible to trace the boundaries of these land units; on the heath they perhaps never were defined; in other areas they often still exist as continuous modern field boundaries, outlining small compact territories of strip form within which lie the settlements of the inhabitants who worked these lands. Good examples of this are seen in the parishes of Portesham, Tyneham, Winterborne Came and Worth Matravers, and a reconstruction of these land blocks and their settlements can be made for the W. part of Purbeck.

Reconstructed Manor Boundaries in West Purbeck

Documentary evidence and the remains of strip lynchets and ridge-and-furrow indicate that many of these land units were farmed, at least in the later mediaeval period, on an open-field basis. This is especially true of the large units with the bigger settlements, e.g. Bincombe, Bere Regis, Coombe Keynes, Fordington, Owermoigne and Winterbourne Steepleton, all of which retained their open fields until a late date. However with the smaller settlements there is less certainty. Some undoubtedly did have open-field systems, but many of those that have always been single farms or tiny hamlets did not, and the land within their territories appears to have been farmed in severalty from the earliest mediaeval period. Indeed in the heathland areas there is no evidence either from documents or from field remains that open fields ever existed. The Enclosure Awards for these areas are always for the enclosure of the heathlands and never of open fields. (fn. 5)

Local Industry

Industry has played only a limited part in the history of this essentially rural region. Iron Age and Romano-British industries of salt and pottery-making and the unique Kimmeridge shale industry were of a minor character; the only large-scale industrial activity until the present century has been that based on the extraction of various building materials, especially the quarrying of Portland and Purbeck stone and the famous Purbeck marble. The industry, though starting in Roman times, was developed in the mediaeval period when, especially in Purbeck, it reached major proportions. The great exploitation of the quarries on the Isle of Portland did not develop until the 17th century and reached its peak in the 19th century.

Second only to the quarrying of stone has been the digging of pipe-clay from the Bagshot Beds close to the N. side of the Purbeck Hills. Pipe-clay has probably been used since Roman times, but its extraction only developed into an important industry in the later part of the 18th century. It provides material for the local manufacture of sanitary ware and for the manufacture of glazed tiles and pottery in Poole, but much larger quantities have been sent to Staffordshire, London and elsewhere.

Cloth-making was once a Dorset industry but in this area was confined to Dorchester and Wareham. A more recent industry carried on in E. Dorset, and in this area in the villages of Bere Regis, Wool and Langton Matravers, was the making of buttons. This was developed in the 18th century and in the early 19th century provided employment for nearly a thousand people in E. Dorset as a whole. The introduction of machine-made buttons after 1851 brought the Dorset manufacture to an end.

Building Materials

S.E. Dorset contains a series of geological formations which have given it not only a beautiful and interesting coastline but also a wide range of building materials. The Kimmeridge Clay has contributed nothing to the builder but, above it, the white oolitic limestone of Portland, long used locally and widely exported to other areas since the 17th century, is probably the best-known building stone in England. Purbeck, a shelly limestone which overlies the Portland, provides stone roofing slates and paving slabs as well as good building stone, and Purbeck Marble occurs as thin layers in the upper beds. In this area Greensand is a poor stone used only occasionally; Chalk forms a backing to more durable materials. Flint has been used in combination with freestone and brick. Carstone or heathstone, a dark reddish-brown iron-impregnated sandstone from the Bagshot Beds, replaces the limestones in the N.E. part of the area, and bricks have been made from a variety of different clays in most parts. Before the growth of brickmaking cob provided a cheap building material where stone was not available. Stone brought from elsewhere for special purposes includes Ham Hill and Bath and Caen from Normandy. There is little of the area that has ever produced good quantities of timber, and surviving timber-framed buildings are few.

The local building stones were already being exploited in Roman times, when a construction of stone foundations for timber-framing was usual for private buildings. Carstone, used in the Roman period, has not been found outside its area of origin, but the limestones were more widely distributed. Purbeck stone, possibly from Upwey, was used in the town wall at Durnovaria (Dorchester), and Portland stone sarcophagi are found in Dorchester as well as in Portland. Purbeck marble was used locally for decorative work and inscriptions and was carried as far as Colchester and Caerwent; it had reached Colchester before A.D. 60. Though flint was used in the chalk areas, there is no evidence in the surviving Roman structures of the use of brick for bonding courses or quoins; these, where they occur, are always of limestone or carstone. Clay was however commonly used for roofing and flue-tiles; local manufacture has not been proved, but it is implied by antefix tiles with a distribution centred on Durnovaria. As well as the local materials, Ham Hill stone occurs in Dorchester for sarcophagi, decorative dressings and walling.

Portland Stone comes of course mainly from the Isle of Portland, but it has also been quarried in Portesham, Upwey, Bincombe, Preston, Osmington and Poxwell. It was the principal building stone used W. of a line from Bere Regis to West Lulworth. All the churches as well as numerous small houses and cottages in this area are predominantly of Portland stone. It is also conspicuous in such public buildings as Weymouth Guildhall and the Shire Hall, Dorchester. Further E., parts of Scaplen's Court (Poole 26) are of Portland, and so too is some of the carved work in Lady St. Mary's church and the 12th-century archway in the boundary wall of the Rectory garden, both in Wareham. Portland stone also underlies the Purbeck in the Isle of Purbeck and was used for part of Encombe House (Corfe Castle 11) to which it was brought from the London Doors quarry near by. Otherwise Purbeck Portland has been worked only from the cliffs between St. Aldhelm's Head and Durlston Head and loaded directly into ships for export to other areas.

Purbeck Freestone from the Isle of Purbeck has been mined for many centuries and more recently obtained from open quarries. The chief workings are in Swanage at Herston, in Langton Matravers at Acton and in Worth Matravers. It is also obtainable from Osmington to Portesham, but in this area the better Portland stone has been most used. Purbeck freestone is the principal building material in the whole of the Isle of Purbeck and is used in Poole (e.g. St. James's church), Wareham (Lady St. Mary's and St. Martin's churches), Wool, including dressings at Bindon abbey, and East Lulworth; in Lulworth castle, however, there is more Portland than Purbeck. To the N.E., Bloxworth church has the nave and S. porch built of good Purbeck ashlar, but otherwise the stone is not extensively used N. of the river Piddle.

The Purbeck Beds also provide the stone roofing slabs used throughout the Isle of Purbeck and intermittently elsewhere and also for the eaves courses of tiled roofs.

Purbeck Marble (fn. 6) is a greenish or reddish limestone crowded with the shells of freshwater pond-snails, which occurs near the top of the Upper Purbeck Beds in two thin bands never more than 4 ft. thick and seldom exceeding 1 ft. There is a line of old workings along the outcrop of the marble from Swanage to Orchard, S. of Church Knowle, namely at Wilkswood, Quarr, Dunshay, Scoles, Afflington, Lynch and Blashenwell. Some of the old disused tracks from these workings, leading towards Corfe Castle, can still be traced.

The marble was highly valued because it will take a good polish. It is best known for its use, especially in the 13th century, for polished shafts, usually darkened with oil or varnish to a shiny black. Owing to the thinness of the bed, shafts have to be cut parallel to the stratification with the result that they tend to flake easily and to be particularly susceptible to frost damage. The only mediaeval use of the marble for shafts in this area is in St. Edward's Chapel in Lady St. Mary's church, Wareham, but it has been widely used for canopied table-tombs, gravestones, coffin-lids and fonts. In the second half of the 19th century it was used extensively in the rebuilding of the parish church of St. Edward, Corfe Castle, and in the building of the new church of St. James, Kingston, in the same parish.

For the wide distribution of Purbeck marble over southern and midland England, to Ireland and to Normandy, reference may be made to the authorities quoted in the footnote, p. xl.

Carstone is the principal stone used in the N.E. part of the area. It is difficult to work and of variable quality and generally inferior to the limestones described above. It has been used for the churches of Morden, Lytchett Matravers, Corfe Mullen and Canford, at Charborough House, at Bindon abbey as a facing to flint rubble, and in the base of the church tower at East Lulworth.

Flint has not been used on its own but provides the rubble core to some of the walls of Corfe castle and Bindon abbey. It was used in bands alternating with freestone in buildings, mostly of the late 16th century, such as Manor Cottage, East Lulworth (5), and Manor Farm, Winterbourne Steepleton (2). In the mediaeval tower of Affpuddle church it occurs with Portland to form a chequer pattern, and in later building it was used in alternate bands with brick, as in the 18th-century work in Bere Regis church.

Chalk, widely available in the area, has been quarried for lime but is too soft for general use as a building stone; in some barns it was used behind freestone or brick.

Greensand, which is widely used further N., in this area has been used only for the dressings of a few 14th-century doorways and windows, at Lychett Matravers, Broadmayne and Portesham.

Cornbrash, a hard compact limestone, has been quarried at East Chickerell and Bincombe for field walls and rough work and in Radipole for lime-burning and railway ballast. No architectural use has been made of it.

Ham Hill Stone, an orange-yellow shelly limestone from Somerset, was used for the late 13th-century window tracery at Moigne Court (Owermoigne 2), but its more general employment for window dressings, tracery and ornamental carved work came later in the mediaeval period. In S.E. Dorset it occurs mainly on the N. fringe of the area, at Dorchester in St. Peter's church and St. George's, Fordington, and at Affpuddle and Bere Regis. Ham Hill stone is also used in Wareham at Lady St. Mary's in a N. window, in the niche over the N. doorway and in the tower arch. Reference has already been made to its use in the Roman period.

Bath Stone, a creamy yellow oolitic limestone also from Somerset, was used extensively for repair work in churches in the 19th century and was then the commonest material for doorway and window dressings. The piers of the arcade in Lytchett Matravers church are also in Bath stone and there is one mediaeval window of it in Corfe Mullen church. There are also Bath stone fireplaces in Scaplen's Court, Poole (26).

Caen Stone, a pale creamy fine-textured limestone imported from France, is the best of all limestones for decorative carved work. The carved door-head of c. 1100 at St. George's, Fordington, is of this material; so too are fragments of decorative carving in a number of other churches. The (1854) arcade of Winfrith Newburgh church is of Caen stone.

Brick. A small fragment of early work at Moreton House suggests the use of brick in the late 16th century, but the earliest complete brick structures surviving are Bloxworth House, perhaps of 1608, the gatehouse dated 1634 and garden walls at Poxwell House and the N. front of Woolbridge Manor, East Stoke (4). In each place the brick is associated with stone dressings; at Woolbridge and in the garden wall at Poxwell it is also diapered with black bricks; the Poxwell gatehouse has brown glazed brick ornamentation. The mid 17th-century Rectory at Hamworthy, Poole (330), shows an ambitious use of ornamental brickwork.

The use of brick, however, did not become general before the 18th century. It was widely used in Poole in the early 18th century; in Dorchester stone facing is rare after the building of Colliton House in c. 1700, and the rebuilding in Wareham after the fire of 1762 was all in brick.

Bricks have been made from the Oxford Clay around Weymouth, at Radipole, at Rodwell in the S. part of Weymouth and at Chickerell where two brickyards are still productive. The clay of the Wealden Beds at Swanage, between Godlingston and Ulwell, has been used for bricks and tiles for at least two centuries. At Broadmayne the Reading Beds gave the brown bricks speckled with black which were extensively used in Dorchester in the mid and late 19th century. There were once six brickyards in Broadmayne as well as one in Warmwell. Some bricks from these works were less well fired, resulting in a plain pink without the speckled effect which was only produced by more intense firing. The Reading Beds have also been worked in the Weld estate at Coombe Keynes for bricks and tiles, but not before 1860.

Bricks have been made from the Bagshot Beds at Moreton, near the railway station, at Studland and at Upton, N.W. of Poole Harbour. It was from Upton that the very pale bricks of Lytchett Minster church were procured (1833). Bricks were also made at one time on the N.E. side of Creech Hill at Cotness Wood for the Bond estate.

Apart from the Broadmayne and Upton bricks already mentioned, the bricks are generally of a good red colour. Two-colour effects are produced by combining plum-red with a browner colour or with a brighter red. Several examples are to be seen in Wareham where white brick is also used to provide contrasting dressings. Dark blue or grey vitrified bricks are used to provide contrasting headers, especially in walls built in Flemish bond, and sometimes for the complete facing of a front wall. The use of header-bond facing in both red and vitrified brick is especially common in Poole but is also found in Wareham and Dorchester.

Timber-framing is rare in this area. There are some framed buildings in Sturminster Marshall, the parish most remote from a supply of building stone, and a dozen have been recorded in Poole, all earlier than the general introduction of brick. In Dorchester a few buildings had framed front walls only, the other walls being of stone; the most conspicuous survivors are Nos. 6 and 7 High West Street. In Weymouth the 'Black Dog' (Monument 173) is partly of timber. Elsewhere remains of timber-framing are fragmentary.

Cob was the traditional building material for domestic work wherever stone was not readily available, and it was extensively used over the whole area N. and E. of the river Piddle until the arrival of machinemade bricks. In the mid 19th century cob with or without a facing of brick was used for several cottages in Tyneham parish, and complete chimneys built in cob have been recorded at Wool (Monument 29) and Steeple (Monument 14). The survival of cob walls in the two lower storeys of No. 16 North Street, Wareham, suggests that many of the stone plinths in the town that now carry brick walls may, before the fire of 1762, have been the base for cob.