Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Britton Street ', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp164-181 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Britton Street ', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp164-181.

"Britton Street ". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp164-181.

In this section

CHAPTER VI. Britton Street Area

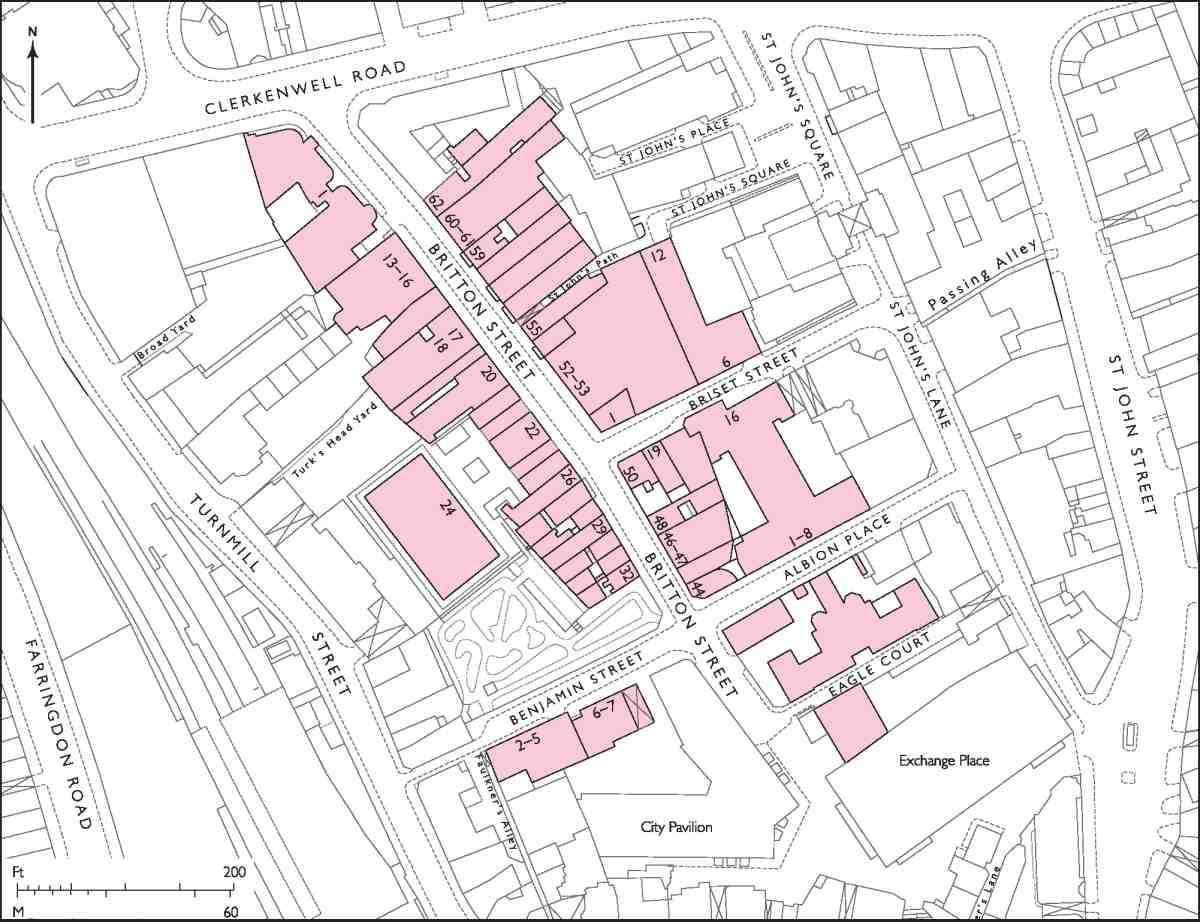

203. Britton Street area

Britton Street was laid out and built up between 1718 and 1724, replacing gardens and small houses on the backlands of Turnmill Street and St John's Lane. It was originally called Red Lion Street, after a tavern at the top end where it met Clerkenwell Green, and was renamed in 1937 after the antiquary John Britton, who served as an apprentice at this establishment, which had by then become the Jerusalem Tavern. The tavern was among a number of houses in the street demolished in the 1870s to make way for Clerkenwell Road. Of the seventy-odd original houses ten survive, five on each side (Nos 27–28, 30–32, 48, 54–56 and 59). Most of these, however, have been re-fronted in whole or part. Just enough remains to preserve some sense of what a London guidebook of 1726 described as 'a fine new Street called Red-Lion-street, which is a very regular and beautiful Building'. (fn. 1)

An ambitious development, Britton Street was the creation of Simon Michell, who also oversaw the building up of a small estate in Spitalfields, owned jointly by him and Charles Wood, during the same period. The Britton Street houses were similar in size to, or rather smaller than, those built there, in Wilkes, Fournier and Princelet Streets. (fn. 2) The largest were at the more desirable north end towards the Green (Ill. 205), similar to the surviving No. 59, and at this end stabling and coach-houses were provided for the wealthier residents. To the south the houses were smaller, Nos 30–32 being representative. The side streets, which did not belong in their entirety to Michell, were mostly built up with small houses, along with two courts on the south side of what is now Briset Street. Much of this housing survived until the late 1950s and early 60s.

Britton Street, or at least the northern half, was soon established as one of the best residential addresses in Clerkenwell, but by the latter part of the century most of the houses were in the occupation of craftsmen and tradesmen, particularly clock- and watchmakers and cabinet-makers; several of the surviving old houses have attic 'watchmaker' windows. Continued commercial and industrial use is reflected in the Victorian and later rebuildings. As late as the 1980s the street retained a predominantly old-fashioned commercial character. This has now disappeared, as buildings have been restored, remodelled or replaced by fashionable newcomers. A very early harbinger of this trend was the arrival here in the 1970s of the architects Yorke Rosenberg Mardall, whose new offices were part of the redevelopment of the Booth's distillery site extending from Turnmill Street.

Among the more recent buildings the most remarkable is the late-1980s postmodern house (No. 44) designed by Piers Gough for Janet Street-Porter.

As well as Britton Street itself, this chapter deals with the side streets Briset Street, Albion Place, Eagle Court and Benjamin Street. These were originally built up with small houses, some of which survived until after the Second World War. Few of the present buildings there are of more than passing interest, but the former school in Eagle Court is of historical significance, an early board school designed for what was then an exceptionally tough neighbourhood. Benjamin Street, descending from Britton Street towards the Fleet, runs alongside one of Clerkenwell's rare open spaces (Ills 203, 204), a former graveyard. This belonged to St John's Church in St John's Square, a vital component in Michell's development.

Early history of the area

Until the Dissolution the land here belonged to St John's priory. It was enclosed by a wall from the late fourteenth century or earlier. A handful of references to the property during the priory's existence refer to it variously as a garden, a meadow and a close. In the sixteenth century it was known as Butt, Bocher, or Butchers Close, the name perhaps indicating that it was used for holding or slaughtering cattle. In extent it ran from the rear of properties in Turnmill Street on the west to the priory's inner precinct on the east, and from Clerkenwell Green in the north to the Bailiff of Eagle's house in the south (see Ill. 129 on page 116). (fn. 3)

After the dissolution of the priory, Butt Close passed through various hands, including those of Thomas Seckford, who acquired it in 1573. In the 1590s it was purchased by John Ballet, goldsmith, of London. (fn. 4) Ballet and his descendants, living at Hatfield Broadoak in Essex, retained the freehold for more than a hundred years, (fn. 5) during which time many buildings were erected on the land and a roadway called Garden Alley was formed. By the later seventeenth century the whole area had become known as Garden Alley or Alleys. At the south end 'an antique dwelling', surviving into the eighteenth century, was traditionally said to have been a dairy-farm belonging to St John's. (fn. 6)

In 1703 an Act of Parliament established a trust to sell the estate, under the terms of a later John Ballet's will, for the benefit of his children. The first portion was sold in 1705. This comprised the north-east corner of the estate, fronting Clerkenwell Green and for that reason probably the most saleable part. At the rear of the site it included two houses, later numbered 71 and 72 Red Lion Street, which had been built some time between 1694 and 1698 by William Bills, a tiler and bricklayer, who lived in one. (fn. 7)

204. Britton (Red Lion) Street area, mid-1870s

The remainder of the estate, including the Red Lion tavern and adjoining houses fronting the Green, was sold to Michell in 1716. (fn. 8)

Simon Michell and the development of Britton Street

The lawyer Simon Michell, the creator of Red Lion Street, was born about 1676, the son and heir of John Michell of Brympton, Somerset, gentleman. He was admitted to the Middle Temple on 10 March 1705 and subsequently to Lincoln's Inn in 1714, when he was described as being of St Andrew, Holborn, gentleman. (fn. 9)

Besides his developments in Clerkenwell and Spitalfields he later seems to have developed or acquired property in Southampton Row, (fn. 10) and at the time of his death in 1750 also owned leasehold property in Turnmill Street, property in St Sepulchre's parish, a copyhold estate at Fulham, and an estate at Alvington in Somerset. From at least 1728 until his death he was a Commissioner of Sewers for Holborn and Finsbury—responsible for much of Clerkenwell (fn. 11) —and he was also a local magistrate. In this last capacity he proved so unpopular that at his funeral the local mob was 'with difficulty restrained … from committing outrage on his remains'. (fn. 12)

At the same time as he oversaw the development of Red Lion Street, Michell was concerned with the creation of the new parish of St John's, Clerkenwell, rebuilding what remained of the former priory church of St John in order to achieve this. Viewed on the map, there would seem to be little to connect the new street with the new church; whereas Red Lion Street, opening into the Green nearly opposite Clerkenwell Close, was admirably placed for easy access to the old parish church of St James. In contrast it was rather ill-placed for access to the church of St John, particularly by carriage. Michell was, however, quite clear that the church was intended for residents of his street. Of the fourteen officers appointed to St John's parish in January 1724, nine, including Michell himself, lived there, and No. 59 was soon acquired as the rectory. (fn. 13)

Red Lion Street was laid out between 1718 and 1720, the upper half following the line of Garden Alleys. It continued southward as far as what is now Albion Place, laid out more than thirty years earlier as George Court and giving access to St John's Lane. The subsequent creation of Benjamin Street extended the line of George Court west to Turnmill Street; at the T-junction six houses numbered in Red Lion Street formed the southern termination of Michell's development. The name first used, Garden Alley Street, was soon dropped for the perhaps better-sounding name Red Lion Street. (fn. 14) This had been selected by 1719, when a lease of the first new houses on Michell's development, running from September 1718, was granted to John Warden, a carpenter who was also building in Coldbath Fields in western Clerkenwell about this time. (fn. 15) These first houses were Nos 69 and 70, with frontages of about 18ft, and another house at the back facing a new mews, called Red Lion Yard.

Nos 2–9, south of the Red Lion Tavern, and the row south of Berkley (now Briset) Street were built in 1720, when work also began on Nos 65–68, south of Warden's houses. (fn. 16) In the following year Michell and others, described as proprietors and builders of new houses in Red Lion Street, were summoned for breaking into the common sewer there. (fn. 17) Late in 1722 Michell, arguing for the creation of the new parish of St John's, claimed that he and his undertenants had already built 80 new houses. However, either this figure was an exaggeration or it included buildings not actually on Red Lion Street, where there were never more than 73. (fn. 18)

Michell retained overall control of the development, but from the outset leased plots to other builders and developers, invariably on 61-year leases, with an initial year's peppercorn rent and between 30s and 40s thereafter for each individual house plot, a rate in many cases of 2s per foot of street frontage. (fn. 19) Apart from Michell himself the chief developer was George Greaves, or Graves, carpenter, at that time living in St Andrew's, Holborn, who also built houses in Berkley Street.

205. Red Lion Street c. 1900, looking north to Javens Chambers, Clerkenwell Road

Robert Tothill, esquire, was a major investor in the development, and Greaves seems to have acted as builder for both him and Michell. Smaller takes were developed by Joseph Jackson, bricklayer, John Warden, and John Warden junior, a plumber. William Bury, esquire, built No. 17, with a brewhouse to the rear, for himself. Jonathan Catlin, victualler, built No. 37 for himself, and William Humphreys, chocolate maker, No. 39 as his own house. (fn. 20) Michell resided at No. 63, the largest house, on a doublewidth plot, and Tothill lived at No. 18 from about 1727 to 1750. (fn. 21) Jackson was living at No. 30 by 1723, and Greaves, too, lived in the street, at No. 51, until his death in 1737. (fn. 22)

By 1724 the whole of Britton Street had been built up, apart from No. 36, the last house on the west side, which seems to have been added as an afterthought, in 1727. (fn. 23) On the east side the building line was broken by Berkley Street and the entrance to Red Lion Yard, and was set back slightly at Michell's own house. Nearly all the houses were of three storeys and attics, most of them with a basement. The larger houses, at the top end of the street, were three bays wide, generally with 20ft frontages, the rest were of two bays with 15ft or 16ft fronts. Simple brick plat-bands marked the storeys, and the windows, with flush-fitting frames, were given gauged red-brick heads. All or most followed the increasingly common two-room deep plan with side passage and rear staircase, corner fireplaces, and closets. The plots varied considerably in length. No. 64, which backed on to the stable yard, had an 'alcove' at the bottom of the garden, as well as access to the stables. Two of the houses built by Greaves in the row south of Berkley Street had workshops behind them from the start, and most of the houses in Britton Street subsequently acquired workshops.

Red Lion Yard (later Mews), completed in 1720–2, provided stabling and coach-houses, with hay-lofts and rooms above. (fn. 24)

Britton Street area houses

206. No. 54 Britton Street in 1946

207. No. 59 Britton Street in 1946

208. Nos 10–14 Benjamin Street in 1946. Demolished

209. Berkley Court in 1899. Demolished

Social and commercial character

Something of the early social tone of the street is indicated by the presence in the 1728 ratebook of seven esquires, Lady Harrison (the elderly widow of Sir Edmund Harrison, who died in 1713) at No. 20, and Sir George Fettiplace, 5th and last baronet, at No. 60, which remained his town-house until his death in 1743. Fettiplace, a bachelor, was worth £5,000 a year and had £100,000 in money. Another wealthy early resident was Aaron Gibbs, 'an eminent rag merchant, reckoned worth £40,000'. (fn. 25)

In the cheaper southern part of the street was a schoolroom at No. 29 by 1729. From the outset there were a number of tradesmen and craftsmen, including, at No. 24, the clockmaker John Maberly, who made the springs for John Harrison's famous chronometer in 1755. (fn. 26)

A long-standing resident was the carpenter and builder Richard Jupp, Master of the Carpenters' Company in 1768. He lived at No. 46 from the mid-1730s until 1745, and then at No. 56 from 1746 until 1780. His son, the architect and surveyor Richard Jupp, was at No. 23 in the 1750s and 60s. A directory of 1774 shows both still in the street, the younger perhaps now living at No. 56 with his father. (fn. 27)

Among other notable eighteenth-century residents were: the Scottish historian of commerce Adam Anderson, who lived at No. 20 for some years until his death in 1765; the prolific author and publisher the Rev. Dr John Trusler, who lived at No. 14 in 1787–8; the engraver James Hulett, resident until his death in 1771; John Coote, bookseller and publisher, who had a shop at No. 14 in the 1770s; John Bevis, physician and astronomer, resident in the 1750s; George Bickham, engraver and writing-master, another resident in the 1750s. The antiquary and clergyman George Ashby was born in the street in 1724, the son of a merchant tailor. (fn. 28)

By the second half of the century Red Lion Street had become one of the centres of the clock and watch industry (confusingly, so had Red Lion Street in Holborn). (fn. 29) In 1760 there were at least six men associated with the trade in the street, and by 1775 at least nine. During the late eighteenth century two of the three largest Clerkenwell clock- and watchmakers were in Red Lion Street: Richard Bayley at No. 12, and Smith & Upjohn at No. 58. Each sold thousands of watches a year, Bayley employing over a hundred people, almost all of whom would have been outworkers. (fn. 30) The watchmaker Josiah Bartholomew was at No. 25 from 1793 until 1847, (fn. 31) during which time his two sons were born: Valentine, an early member of the Society of Painters in Watercolours and Flower Painter in Ordinary to Queen Victoria; (fn. 32) and Alfred, architect and architectural writer, responsible for the Finsbury Savings Bank in Sekforde Street (see page 82).

A number of cabinet-makers lived and worked in the street. William Gomm was at No. 20 in 1770–4, while his son Richard lived near by in Clerkenwell Close. Peter Francis Mallet, a partner in their firm at one time, was at No. 8 between 1766 and 1776, when the Gomms went bankrupt. Mallett took over their business, Richard Gomm then succeeding him at No. 8 for a few years. (fn. 33) Bryan or Bryant Rushworth Thompson, a dyed-chair maker, included in Sheraton's 1803 list of master cabinetmakers, was at No. 62 from 1790 to 1824. (fn. 34) No. 67 Red Lion Street was occupied in the early 1790s by Willoughby Brewer, carver, gilder and looking-glass manufacturer, and at Nos 69 and 70 was a firm making medicine chests. (fn. 35)

Red Lion Street had three places of refreshment, two of them called the Red Lion. These were the Red Lion Tavern at No. 1, later the Jerusalem Tavern; the Red Lion alehouse at No. 48, in business by August 1721; and a coffee-house at No. 27.

The social decline of the street is epitomized by the fate of Michell's own house, No. 63. After Michell's death, the house was occupied by John Darker, Esquire, a former Smithfield hop merchant who became treasurer of St Bartholomew's Hospital, and then by William Wildman, a Smithfield meat salesman, who moved here in 1761 from No. 53, where he had lived since 1749. Wildman became well known after his purchase in 1765 of the racehorse Eclipse, which, as a breeding stallion, laid the basis for the modern thoroughbred racehorse. (fn. 36)

Wildman remained at No. 63 until his death in 1785, when he was succeeded by James Wildman, perhaps a son, until 1789. Later the house was occupied by a tobacconist, Samuel Fish. (fn. 37) In 1810 it was divided into three, and an iron foundry constructed in the back garden. (fn. 38) This was demolished in the early 1830s and fifteen diminutive houses built on the site, named Albert Place in 1842. (fn. 39)

By 1841 Red Lion Street had become almost wholly commercial, with more than fifty trades and industries represented, and at most only seven exclusively residential properties. (fn. 40) The only professionals were a solicitor, the incumbent of St John's Church, a schoolmistress (there was still a school in the street), and a surgeon, while No. 17 was used as an Excise Office. By the 1850s the whole of this area was thickly populated, many inhabitants working in the jewellery, watchmaking and allied trades, such as lapidaries and engravers, who worked from home. Houses were by then in multi-occupation, families sharing ill-constructed water-closets set up in the passage at the bottom of the (unventilated) staircase, often alongside the dustbins. 'Here is much need for sanitary reform', noted Pinks. (fn. 41)

Many of the innumerable goods manufactured here were natural progressions from the clock trade, such as the making of scientific instruments. Other products included cameras, eye protectors, metal fanlights, toothbrushes and teapot handles. There was also William Eates, at No. 12 in 1880 making drum battledores, a sort of early badminton racket of wood and parchment popular with children. (fn. 42) Alongside the manufactories a baker, dairyman, greengrocer, oilman, and tailor could all still be found at the end of the century. (fn. 43)

The increasing poverty and crowding of the area led to the establishment of missions here. No. 10, which had been registered as a place of Nonconformist worship in 1835 (fn. 44) and was later a British and Foreign School, became a Baptist chapel in 1868. Baptists also had mission rooms at No. 61 from about 1877 until 1908. The Lamb and Flag Ragged School moved into No. 13 after their premises were demolished in the 1870s for Clerkenwell Road, and took over the Baptist chapel in 1880. The number of scholars attending the various classes there around 1900 exceeded 500. The schools continued to be associated with the work of the London City Mission, and a mission hall or room was opened at No. 10, where evening gospel services were held, on Sundays attracting over 500 people. (fn. 45) By 1920 the building had been turned into the London Shoeblack Brigades' and Cripple Boys' Boot Repairing Centre, but by the end of the decade had been absorbed by the sweetmakers Murrays (see page 194). (fn. 46)

Traders in Red Lion Street in the 1920s included an ostrich-feather dyer and a wooden-pulley maker, but metal-working and scientific and technical manufacturing preponderated, with surgical and scientific instrument makers, chemical glass blowers, electroplate manufacturers and workers in brass, copper and silver. The clock and watch industry was still represented, too. At No. 56 were the General Union of Heating and Domestic Engineers' Assistants and the Amalgamated Portmanteau, Bag and Fancy Leather Workers Trade Society, while at No. 26 was Frederick Baragwanath, advertising artist, an exhibitor at the Royal Academy before the First World War. (fn. 47) By the early 1930s all the professional occupants had gone, and No. 59, no longer the rectory, was occupied by a manufacturer of 'poultry appliances'. (fn. 48)

Until the Second World War this was a generally thriving commercial district, with large warehouses and a coldstorage depot at the upper end of the street. By the early 1970s the relatively few businesses left included wholesalers, suppliers of materials for engraving and printing, a manufacturing optician's and several engineering firms, including makers of burglar alarms and fire-escapes. (fn. 49)

Redevelopment since the late nineteenth century

The proposals put forward in 1871 by the Metropolitan Board of Works for what was to become Clerkenwell Road required the demolition of a number of buildings at the north end of Red Lion Street. More drastically, it was intended that this end of the street should be closed up, as the gradient of the new road as then proposed would have made a junction impracticable. The Vestry, which had been enthusiastic about the street improvement, only realized the full implications at the last minute, but managed to avert the closure. (fn. 50)

Acquisition of the affected properties began in 1873 and continued until 1877. (fn. 51) The Jerusalem Tavern and six houses (Nos 2–7) were demolished on the west side of Red Lion Street, and fifteen on the east side (Nos 63–77), together with Red Lion Mews and Albert Place. (fn. 52)

The opening of Clerkenwell Road does not seem to have had any particular effect on the street, and it was not until about 1890 that a number of the original houses were pulled down for new warehouses and factories, a process that gathered pace in the 1900s. In 1911, however, Sir Walter Besant could still remark on the numerous old houses still standing, many 'sadly fallen in degree'. (fn. 53)

No. 57 was replaced in 1889–90 with the present Queen Anne-style warehouse. It was first occupied by the Albion Iron & Wire Work Co. Ltd, (fn. 54) which was to remain in the street until the 1980s. (fn. 55) No. 62 was built in 1898–9, to designs by William G. B. Lewis, architect, of Hackney, (fn. 56) and Nos 60 and 61 about 1910, in matching style, for Borgzinner Brothers Ltd, manufacturers of jewellery cases and display fittings. Their architect was Walter Pamphilon. (fn. 57) A six-storey warehouse (since demolished) was built at Nos 8–9 in 1901–2 for the stationers Castell Brothers of Clerkenwell Road. (fn. 58) The plain, red-brick factory or warehouse at No. 50 was built about 1904. (fn. 59) Nos 13–16 (now extended as part of a residential conversion) were rebuilt in 1901–5 as warehousing or factories for the developers Mark Bromet and Henry Rosenbaum. The building, with a streaky red-brick and stone façade (all that now survives) was designed by the architect Robert W. Hobden of Finsbury Square. (fn. 60) Nos 15 and 16 were immediately taken by Murrays of Turnmill Street, who by 1907 had also acquired Nos 13 and 14. (fn. 61) No. 29, a four-storey building of 1907, was first occupied by the Farringdon Engineering Co. (fn. 62) No. 58 was rebuilt in 1913 as a platechest factory. Nos 18 and 19, a five-storey warehouse or factory of yellow brick, was built in 1914–16 for J. H. Taylor, manufacturing opticians of Hatton Garden, who occupied No. 19, a firm of electroplate engineers taking No. 18. In 1928–9 No. 20 was rebuilt for Taylors in matching style, the architects being S. Clifford Tee & Gale, of Moorgate. (fn. 63) No. 49 was rebuilt in 1939 apparently as a speculation by the builders, Arthur J. King Ltd of Kingsland. (fn. 64)

Bombing in the Second World War destroyed Nos 33–35 and 42 Britton Street, and the top end of the street on the west side was also badly hit. Other houses, including Nos 20–25, were severely damaged. (fn. 65) After the war, the bombed Clerkenwell Road corner was acquired by Booths for their new Red Lion Distillery (see page 197), leaving their Turnmill Street works behind Britton Street redundant. In the late 1950s and early 1960s there was more demolition of the old houses, including all those remaining in Benjamin Street and the row of six that had formed the southern terminus to Britton Street, which was then extended as far as Eagle Court. Redevelopment of the old Booths site, not completed until the late 1970s, involved transplanting the grand façade of the Edwardian distillery from Turnmill Street to front new flats, an intimation that Britton Street was to outstrip its neighbour in the regeneration stakes. More recently, the development of the Danish Bacon Co.'s site on the north side of Cowcross Street has involved the further extension of Britton Street, which now ends in a piazza in front of City Pavilion and Exchange Place (page 196).

Three more large developments were carried out in the late 1990s. On the site of Nos 51–53 Britton Street and 1–31 Briset Street business units and flats were built to designs by the architects Green Moore Lowenhoff (later GML Architects), then based at No. 48 Britton Street. At Nos 13–16 the Victorian warehouse façade was retained for another residential scheme, Clerkenwell Central, a Persimmon development, which extends through to Turnmill Street. The architects were again Green Moore Lowenhoff. Next door, on the large site formerly occupied by the Red Lion Distillery, No. 1 Britton Street was designed by the same practice. Built in 1998, it comprises a double-height ground floor for commercial use, with flats above and a glass-walled penthouse. (fn. 66)

Individual streets and buildings: Britton Street

Red Lion Tavern (demolished)

The Red Lion Tavern not only gave the street its original name but, indirectly, its present name. A substantial brick building of the late seventeenth century, it was either built as or soon became a coffee-house, in the hands of Ralph Kingston, victualler. By 1720 Kingston had gone and it had become the Red Lion. From the mid-eighteenth century the tavern was run by the Haughton family. James Haughton Langston, a wine merchant of Crutched Friars, took over the lease in 1753, when the building was described as 'now or lately empty and untenanted', and called it the Jerusalem Tavern, taking the name from the tavern in Aylesbury Street formerly run by the Haughtons. (fn. 67)

In the late 1780s the Jerusalem Tavern was occupied by a wine-merchant, James Mendham, who took on as apprentice John Britton. The future antiquary and topographer spent a miserable five and a half years there working in the cellars, and secretly reading books he bought cheaply at nearby stalls. It was through a local clock-dial painter that Britton was introduced to Edward Brayley, who was to collaborate with him on The Beauties of England and Wales. (fn. 68)

The building, which had reverted from a wine-merchant's to an ordinary public house, was demolished in 1877 for the creation of Clerkenwell Road. (fn. 69)

No. 24 and Mountford House

210. No. 24 Britton Street in 2007, looking north across St John's Gardens. Yorke Rosenberg Mardall, architects, 1973–6

211. No. 24 Britton Street. East front, 2006

Mountford House, a small block of flats, occupies the site of Nos 20–25 Britton Street, demolished in the 1960s following war damage. It was built in 1974–7 as part of the redevelopment of the former Booth's distillery in Turnmill Street, and incorporates the much restored 1901–3 façade from the distillery offices, designed by E. W. Mountford (see page 197). Through the ground floor is a passageway to the present No. 24, an office block overlooking St John's Gardens in Benjamin Street, which was enlarged as part of the same development. (fn. 70)

212. Mountford House, Britton Street in 2006. Yorke Rosenberg Mardall, architects, 1974–7, incorporating façade from Booth's Distillery offices, Turnmill Street (E. W. Mountford, architect, 1901–3)

The ensemble was the work of the architects Yorke Rosenberg Mardall (YRM), whose own offices these were. It is of interest for several reasons, firstly as one of the earliest manifestations of Clerkenwell's rediscovery as a desirable area in which to work and live. The preservation of the Mountford façade was seen at the time as representing 'something of a successful counterattack' by the Greater London Council's Historic Buildings Division and Islington Council's Conservation Section against indiscriminate destruction. (fn. 71)

Architecturally, the development has two aspects which mark it out from the general run of new offices and flats in inner-city areas. The first is the landscape setting towards Benjamin Street, with gardens on two sides (Ill. 210). The second is the theatricality of the Modernist building revealed behind the Baroque curtain of Mountford House. This was a trick that the architects CZWG were to repeat a decade later with their own postmodern offices behind a Victorian former warehouse in Bowling Green Lane (see page 70).

Then based in Greystoke Place, Fetter Lane, YRM acquired the site in 1971, when the whole of the Booths site, stretching through to Turnmill Street, was being redeveloped to designs by the Fitzroy Robinson Partnership for the Amalgamated Investment & Property Co. Ltd. (fn. 72) Permission for redevelopment with warehousing and offices had originally been given in 1963, but when approval was sought to increase the amount of offices, the planners were able to press for the Mountford façade to be saved, the intention being that it would be re-erected as a screen alongside St John's Gardens (where, because of the difference in ground levels, the lowest storey would have been hidden from view). In 1971 the former distillery offices were demolished and the stones of the façade put into storage, work beginning on a new office building at Nos 76–86 Turnmill Street (see page 198). Foundations were laid for a warehouse behind, siding on to Turk's Head Yard.

YRM took over the proposed warehouse and the eastern part of the site, fronting Britton Street, continuing the new building to their design as offices. Victor Kite was the project architect, working with YRM partner Brian Henderson. Building work was held up for a few years by the planning process. The provision of flats on Britton Street was a planning condition, and it was the architects who realized that the salvaged façade was just the right width for re-use there. When it came to re-erection, the Bath stone of the upper floors and parapet was too decayed to use and had to be renewed. Vertically, the façade was made to fit by creating split-level studio flats at first-floor level, and two mansard floors were added. Overall, there was inevitable dilution of the original character of the façade, with the altered functions of the ground-floor openings, and the loss of the tall chimney stacks which were a feature of the building in Turnmill Street, and the original leaded 'bottle-glass' windows (Ills 212, 248).

The Britton Street offices consist of two basement levels, extending from Mountford House, and a threestorey pavilion with a recessed ground floor, set back from the flats across a courtyard with a well providing top-lighting. Where the fall in ground level from Britton Street to Turnmill Street exposes the basement levels, they are faced with brown engineering brick matching that of the courtyard paving, so heightening the effect of a podium. The steel frame of the structure, on a 1.8m grid, is expressed externally by aluminium cladding, painted Pompeian red (Ill. 211). The plant that usually clutters the flat roofs of such blocks was put in the basement (or, in the case of the air-conditioning, on the roof of Mountford House), and the roof was covered in concrete tiles patterned to the same grid as the elevations. Internally, the space was largely open-plan around a central service core, and fitted out with classic modern furniture. Overall, the design is Miesian, reflecting the influence of North American Modernism on the firm at this time, and very different from YRM's previous office in Greystoke Place, of 1960–1, with its white-tiled exterior. Inside the courtyard, there is no reference to Mountford's Classicism, the rear elevation of the flats being treated in a Modernist manner.

Critics approved the office pavilion in variously exotic terms: appearing 'to hover with a detached, almost Palladian air'; (fn. 73) 'sphinx-like'; (fn. 74) 'exuding an almost oriental, meditative calm'. (fn. 75) More recently, it has been described as 'a rare example of the International style at home in a historic urban context'. (fn. 76)

YRM remained here twenty years, finally refurbishing and extending the building for a design company, the Overland Group, in the late 1990s. The central cores were altered to create layout and production spaces, with galley kitchens for design teams working long hours, and a staff restaurant was put in on the ground floor. In the court yard, the light-well was deepened. The main alteration was the addition of a roof-top extension, identical in style to the rest of the building, but set back so as not to upset the original view from the courtyard.

213. Nos 27–32 Britton Street (right to left) in 2007

Nos 27–30

The original row of four houses was built by Joseph Jackson on lease from Simon Michell in 1722–3. (fn. 77) Nos 27 and 28 had been roofed by July 1722. No. 27, with a wider (20 ft) frontage was the only one of this run to have a basement with an area. It was originally of three storeys and attic over the basement, but has subsequently been given an additional storey. The first occupant was Caleb Colchester, who had a coffee-house here in 1723–31. (fn. 78) Jackson took the plots for Nos 29 and 30 in 1723, and himself lived at No. 30. (fn. 79)

214. No. 31 Britton Street. Ground-floor plan in 2004

215. No. 44 Britton Street. View from south-west in 2006. Piers Gough, architect, 1986–8

No. 29 was completely rebuilt as offices and showrooms in 1907, and Nos 27 and 28 have seen some rebuilding: No. 27 in 1971, when the top storey was added, and No. 28 in 1991, after a fire (Ill. 213). At No. 30 the house survives essentially intact, though the front has long been stuccoed over, with moulded surrounds to the windows. Original panelling and partitions survive in the upper rooms, and a small marble fireplace on the ground floor. (fn. 80)

No. 29 has recently been transformed into a house and studio for two artists. The work, completed in 2005, is by Tony Fretton Architects, and is claimed to follow the tradition of E. W. Godwin's studio houses, exemplified by that he designed in 1877 for Whistler in Tite Street, Chelsea. The attic was replaced by a full-height storey, and the front rendered a matt purplish-grey. The living accommodation is on three floors, with studios occupying the top storey and the extended basement. (fn. 81)

Nos 31 and 32

Two of a run of five houses built by the carpenter George Greaves, Nos 31 and 32 had been completed by July 1723. (fn. 82) Like the smaller houses in the street generally, neither have basements. The fronts have been rebuilt, the windows with reveals and segmental rather than square heads, and shopfronts have been inserted. No. 31 (Ill. 214) retains much of the original joinery, including panelling and a number of cupboards, some built in to the party wall with No. 32, as well as original cornicing.

No. 44

This much-publicized house was designed by Piers Gough of CZWG for Janet Street-Porter, and built in 1986–8. Architect and client were fellow students at the Architectural Association, but Street-Porter did not pursue a career in architecture, turning to journalism and becoming well-known as a television personality. The builder was another alumnus of the AA, Mike Di Marco. (fn. 83)

The prominent site, on the corner of Albion Place, had been left vacant after wartime bombing, and the vicinity remained down-at-heel when this startling new building was proposed. In its basic elements, the house is conformist enough: two brick façades of Georgian proportions, linked by the canted corner, one of two bays, the other of six (Ill. 215). To this is fused a pattern of giant diagonal square grids, expressed in the glazing bars and sliced-off windows, and emerging beyond the façades as screens of steel lattice. This geometry dictates the gable on the Britton Street front and the steep, polygonal roof. The brickwork is graduated in four shades from brown to buff, apparently to suggest the shadow-play of sunlight, (fn. 84) and the windows have concrete lintels in the rustic form of logs. The roof, originally to have been green, is covered in deep blue pantiles, a controversial choice of material, eventually approved by Islington Council's planning committee against the advice of the planning officer. (fn. 85)

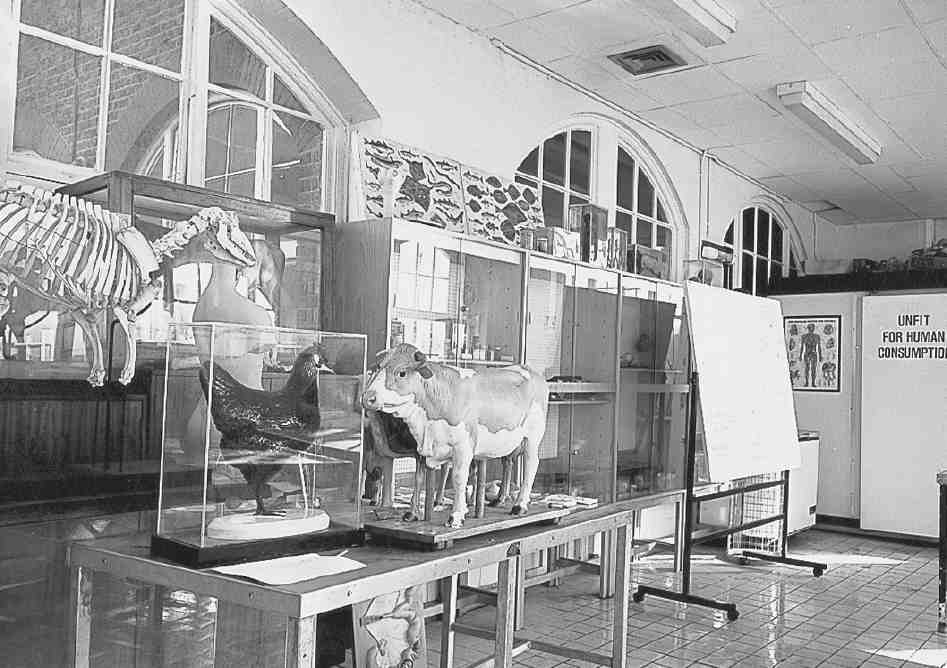

There is no front entrance, but a gate on Albion Place opens on to a small courtyard at the rear or side, where the wall of the house is curved to let light into the adjacent house, since demolished. Inside, the main staircase follows the curve. Canted at one end and bowed at the other, the house has an eccentric plan, with odd-shaped rooms (Ill. 216). The top floor, giving on to a roof-garden, was designed as a work-space and is approached by its own external spiral stair.

216. No. 44 Britton Street, plans in 1988: (1) Guest bedroom (2) Billiard room (3) Dressing-room (4) Bedroom (5) Kitchen (6) Dining area (7) Living-room (8) Studio

With its exaggerated angularity and whimsical detail, the house—its exterior conceived by Gough as 'a kind of portrait'—reflects the strident individuality projected by Street-Porter. A self-parodying sense of humour was expressed by a pirate flag she used to fly from the roofterrace and a sign on the street door reading 'Chat Lunatique'. A number of features were her own ideas, though some, such as an entrance door made of railway sleepers, proved impracticable. (fn. 86)

Janet Street-Porter sold the house in 2001, commissioning David Adjaye to design a new home in Clerkenwell Close (see page 65).

No. 48

This house was part of a terrace of eight (Nos 43–50) built by George Greaves in 1720 and assigned to Robert Tothill. It was originally an ale-house called, like the tavern at the top of the street, the Red Lion. (fn. 87) From about 1883 it was a full public house and known as the Red Lion and French Horn. (fn. 88) After the pub's closure in the mid–1930s the building was occupied by a firm of glass-benders, W. Rayment & Co., who moved here from No. 30, and later for many years by A. Grohmann Ltd, antique dealers. (fn. 89) It was briefly the Cylinder Gallery, before being refurbished in 1993 as offices for the architects Green Moore Lowenhoff, and has since been converted to a dwelling-house.

The second-floor front is clearly not original. The stucco decoration on the first floor may possibly date from 1871, when a long lease was granted. (fn. 90) In 1993 the ground floor retained tongue-and-groove panelling in the front and back rooms, and some original panelling in the firstfloor front room.

No. 54

Built in 1722 by George Greaves, this is one of the least altered of the original houses, and is representative of the larger, three-bay type. (fn. 91) The second-floor front has been rebuilt (Ills 206, 217, 218).

217. Nos 53–57 Britton Street (right to left) in 2006

Following a typical pattern of occupation, during the nineteenth century a succession of manufacturers lived or worked in the house. It has some connection with the engineer (Sir) Henry Bessemer, inventor of the Bessemer steel-making process. He probably lived at this address with his father, Anthony, a letter-founder, who moved here from Hertfordshire in 1830, remaining for a couple of years. (fn. 92) In the late 1930s the building became the offices of the Cowcross Cold Storage & Transport Co., who erected a cold store on the large site to the side and rear, extending to Briset Street. (fn. 93)

218. Nos 54–56 Britton Street (right to left). Elevations in 2004

219. No. 55 Britton Street, shopfront in 2007

The house remained in office use until the end of the 1990s, and in 2001 was restored to use as a single dwelling. (fn. 94) The cold store, a low-rise, plain brick building with two low gables to Britton Street, was designed by Gilbert Bath of Chelsea. Latterly used as a car park, it was demolished in 1998 and replaced by apartments and retail space, numbered 52–53, by GML Architects. (fn. 95)

No. 55

This house was one of a row of five built by George Greaves (Nos 51–55, 51 being his own house), and dates from 1722. From the front, however, it has the appearance of a house built a century later (Ills 217–219). The façade and shopfront cannot be precisely dated, but probably belong to the occupancy of William Anthony, a successful and distinguished watchmaker, who was here from 1800 until the late 1820s. (fn. 96) The house was apparently uninhabited in 1830, but was occupied from 1831 by Edward Walker, a watch-tool maker, who moved here from No. 27. (fn. 97)

Some original features survive on the upper floors, including panelling, but none of the fireplaces. In the 1990s the upper floors were converted from offices back to residential use, and the ground floor was opened as a pub, the Jerusalem Tavern, owned and run by St Peter's Brewery of Suffolk (Ill. 220).

St John's Path, the alley over which the house is partly built, pre-dates Simon Michell's development. It was known as St John's Passage until 1939.

220. No. 55 Britton Street, ground-floor bar in 2006

No. 56

Robert Tothill took a lease of this plot in September 1722, along with two to the north, each having a 20 ft frontage to the street, allowing the houses to be three bays wide. Tothill's builder may well have been George Greaves, who was a witness to the leases. (fn. 98) The carpenter and builder Richard Jupp lived here from 1746 to 1780.

The first-floor windows have been lowered and Neoclassical iron balustrades added to form little balconettes (Ills 217, 218). Some original, or early, internal fittings survive, including panelling and the open-string staircase. A decorative cornice in the first-floor front room, dado rail, chimneypiece and grate are probably contemporary with the lowering of the windows, representing a refurbishment of the early nineteenth century.

No. 59

This is the sole surviving house built for Simon Michell himself (Ill. 207). It had been built by December 1722, when the empty property, along with Nos 60 and 61, was insured. (fn. 99) In 1724 Michell sold it for £650 to the Commissioners for Fifty New Churches, as the rectory of St John's Church. (fn. 100) It remained the rectory for over 200 years, until sold in 1932, although the first and several later incumbents did not reside there. In the 1830s, for example, it was occupied by a goldsmith. (fn. 101)

In 1871, having been let out in tenements and occupied by five or six families, the house was in a very poor state of repair, most of the woodwork broken, rotten or missing altogether. The mantelpieces had gone and the stone paving in the kitchen had been replaced by a wooden floor. (fn. 102) However, the original doorcase with fluted pilasters and elaborately carved brackets supporting a flat hood survives, as does some of the panelling, cornices on the second floor, and the stairs, with their column-on-vase balusters and turned newels.

Briset Street

Until 1936, when it was renamed after the founder of St John's priory and St Mary's nunnery, Briset Street was called Berkeley or Berkley Street. It was also known in the eighteenth century as Bartlett Street—or Bartlets Street, as it is shown on Rocque's map—from a long-standing corruption of the name Berkeley. The street originated as a passage off St John's Lane, running along the north side of Berkeley House. After the demolition of the house in the late seventeenth century, the eastern end of the passage, then called Martin Street, began to be developed, being described as 'new' in 1714, when houses were also being erected in Francis Court, off the south side. Most of the houses here and in Berkley Court followed in 1720–1. Much of the ground had been acquired by Simon Michell along with the site of Britton Street and he, with the builder George Greaves, carried out some development at the western end of the street. The remainder was built up by a consortium of builders and craftsmen including William Stortham, bricklayer, and Samuel Phillips, glazier and carpenter, both of St James's, Westminster. They were also involved in the development of Berkley Court. (fn. 103)

221. Nos 16 (left) and 17 Briset Street in 1994

None of these early buildings survive, and both Berkley Court (Ill. 209) and Francis Court disappeared in clearance after the Second World War. Briset Street is now mostly taken up by recent apartment blocks. On the north side, No. 6 is a large block with four main storeys and a deep basement, comprising offices and flats. Built c. 2000 to a brief developed by Hemingway Properties, it has a concrete frame neatly fronted with terracotta panels between the windows. Its rear elevation at No. 12 St John's Square is rendered, and joined up by means of similar detailing with Nos 14–17 to the east. On the south side are one surviving house (No. 16), probably a rebuilding of the early nineteenth century, and No. 17, a plain red-brick workshop built about 1905. It was early on a type-foundry, and was later for many years occupied by A. H. Rowley Parkes & Co., one of the last Clerkenwell firms to make clocks by hand (Ill. 221). (fn. 104)

These buildings now form part of a residential block for students of City University, Francis Rowley Court. Completed in 1995, this extends back from Albion Place.

222. Albion Place in 1902, looking east towards the Old Baptist's Head public house and No. 31 St John's Lane. Demolished

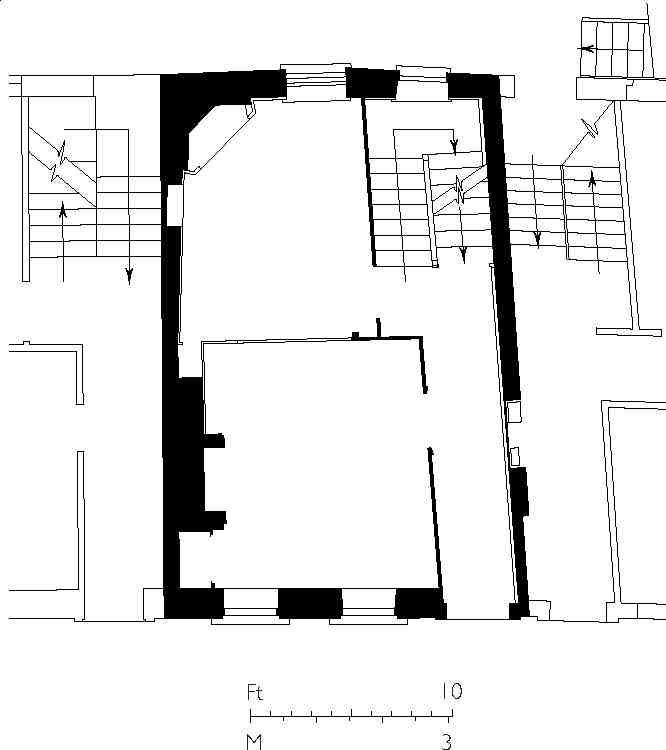

223. Eagle Court School. Plans as built. E. R. Robson, architect, 1873–4

Albion Place

In the early twentieth century, Sir Walter Besant dismissed Albion Place as 'a mere flagged passage or footway, with the courtyard wall of a board school on the south side'. (fn. 105) The north side, in fact, was entirely lined by three-storey houses, as the south side had been before the school was built. Albion Place was formerly called George, George's or St George's Court, described as 'new' in 1687. (fn. 106) Christopher Pinchbeck, originator of the eponymous alloy, a maker of watches, clocks and musical automata, worked here, leaving for Fleet Street in 1721. (fn. 107) The court was rebuilt from 1822 under the present name, with houses 'in a neat style' (Ill. 222). (fn. 108) Many of these survived until the late 1960s.

Eagle Court

Former Eagle Court School

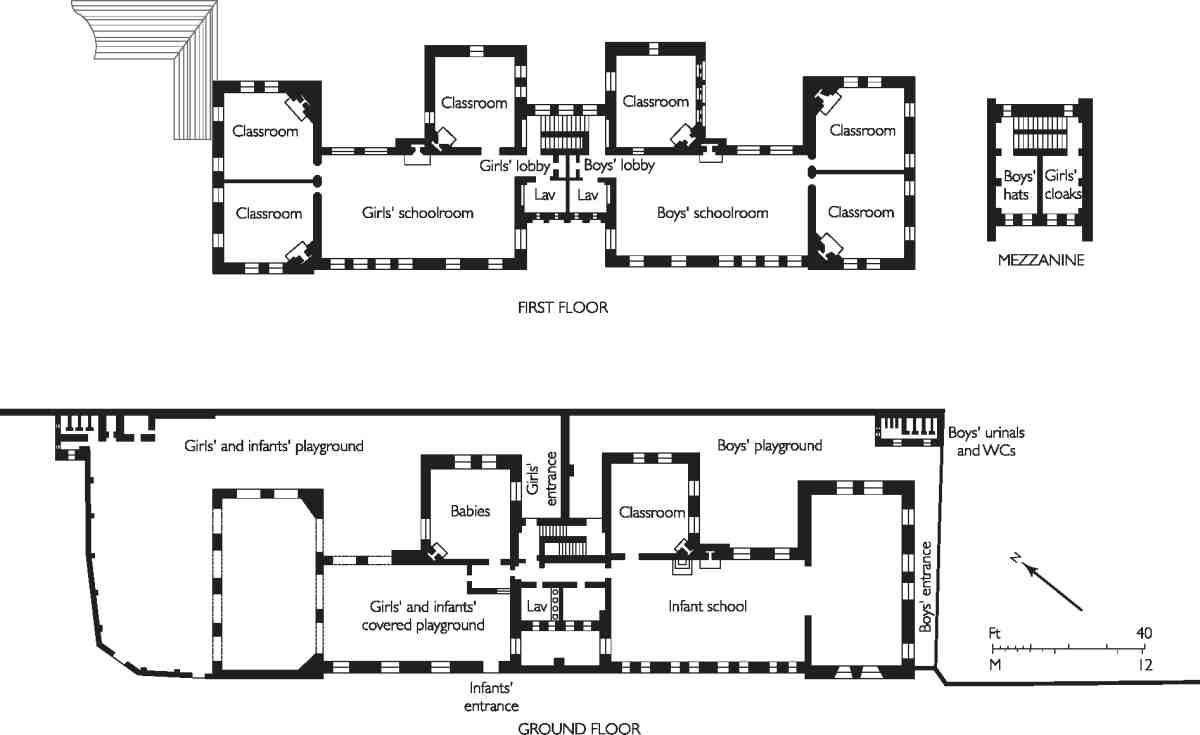

Built in 1873–4, this was one of the first schools designed for the London School Board by its in-house architect, E. R. Robson (Ills 223, 225). (fn. 109) Originally called Eagle Court School, it was later known as St John's Lane Elementary School.

As with other early board schools, the location was chosen precisely because of its dense, impoverished population. Eagle Court was so notoriously lawless that a police guard had to be mounted to protect the workmen and site during construction. (fn. 110) The new school, for over 800 pupils (326 infants, 246 girls and 246 boys), was built by W. Wigmore of Fulham.

Robson maintained that 'in such a neighbourhood, shut in from all possibility of being seen, the plainest of plain structure could alone be suitable'. (fn. 111) Consequently there is little in the way of ornamentation beyond the contrast in the brickwork between yellow stocks and red dressings, and some herringbone panels. The gables are straightsided, and the windows segment-headed.

Because of the narrowness of the street the height was limited to two storeys so as not to overshadow the houses opposite (Ill. 224). Both boys and girls were therefore accommodated on the first floor, the infants occupying the ground floor in the usual way. The girls' and boys' departments were served by a 'double stair'—two stairs in one compartment, separated by a spine wall—to ensure segregation, cloakrooms being provided in a mezzanine off the stairs. In overall plan, the building was a double-U shape, to allow for adequate natural lighting; for the same reason, a recess was left in the long front of the building so that the schoolrooms could have windows at the ends (Ill. 223).

Additions and improvements were made in 1894 under Robson's successor, T. J. Bailey, including the provision of new staircases (replacing the double stair), teachers' rooms and an infants' hall. (fn. 112) Plans to expand the school in 1912 were shelved after the outbreak of the First World War, during which the number of children in the area declined to the point that the school was closed at the end of 1918. (fn. 113)

224. Eagle Court, 1874. Looking east towards St John's Lane, with Eagle Court School on left. Mostly demolished

Briefly, the school was one of the Day Continuation Schools set up by the London County Council following the 1918 Education Act, to provide further education for school leavers. A substantial sum was spent converting and equipping the building, but financial stringencies and opposition from employers and parents stifled the initiative, and all the LCC's continuation schools were closed in the summer of 1922. (fn. 114)

The building's educational function was continued when in 1923 the LCC leased the school to the Cordwainers' Technical College as a replacement for their old premises in Bethnal Green. The college, which added a two-storey rear extension in 1931, moved to Hackney about 1939. (fn. 115) In 1942 the building was adapted to house the LCC Smithfield Institute (formerly Smithfield Meat Trades Institute). Over the next half-century the institute became successively the LCC Smithfield College of Food Technology (1947), the National College of Food Technology (1950), a branch of the College of Distributive Trades (1960), and, finally, in the late 1980s, having merged with the London College of Printing, the London Institute. In the mid-1960s an annexe was built on the corner of Albion Place at No. 42 Britton Street; this provided classrooms, an office and a library in a flat-roofed, two-storey block designed by Dennis & Associates. (fn. 116)

Within the old school building, much of the interior remained remarkably intact when the Institute closed in the 1990s, including a sliding partition between the easternmost classrooms, with ball finials, identical to one illustrated in Robson's School Architecture of 1874. (fn. 117) Despite the various alterations since the late nineteenth century, the building is (with the Camden Institute, formerly Mansfield Place School) almost the only early Robson school to retain its original layout substantially intact.

Benjamin Street

Benjamin Street runs uphill from Turnmill Street, and is the only through turning from that street, once lined by numerous courts and alleys. Most of the land here lay outside Simon Michell's estate, but it was probably his Red Lion Street development that prompted new housing to be built here in about 1725. John Collins, a bricklayer of St Ann's Westminster, pulled down 10 of 11 existing houses, and built 15 new properties in the street 'called or intended to be called Benjamin Street'. (fn. 118) Why this name was chosen is unknown.

The houses on the north side had the tiniest of back yards, bordering directly on Michell's land. They were only demolished in the 1960s (Ill. 208). On the south side the plots were deeper. Nos 8 and 9 survived into the 1950s, but the other houses were replaced by two warehouses in the nineteenth century. The present buildings on the south side of the street are three in number. Nos 2–5 is a Victorian warehouse, internally altered and externally rendered by Westmore & Partners, architects, in 1966–7. (fn. 119) Nos 6–9 (Albion House) began life as an industrial building, erected in two stages to the designs of Westmore & Partners in 1964–7. The exposed concrete frame was retained when it was converted for flats as the Cowcross Refuge Building by EPR Architects in 1997–8. (fn. 120) The corner with Britton Street is occupied by part of City Pavilion (see page 196).

St John's Gardens

This small public garden originated as a burial ground for St John's Church, which had only a very limited graveyard. The original site, hemmed in by buildings in Turnmill Street, Benjamin Street and Britton Street, was given or sold to the parish in 1754 by Simon Michell's son John, in accordance with his father's will. (fn. 121) The ground (just outside Clerkenwell proper, in the parish of St Sepulchre Without) continued to be used for interments for almost a century until it was closed under the Burials Act of 1853.

225, 226. Former Eagle Court School in 1989, during occupation by the London Institute

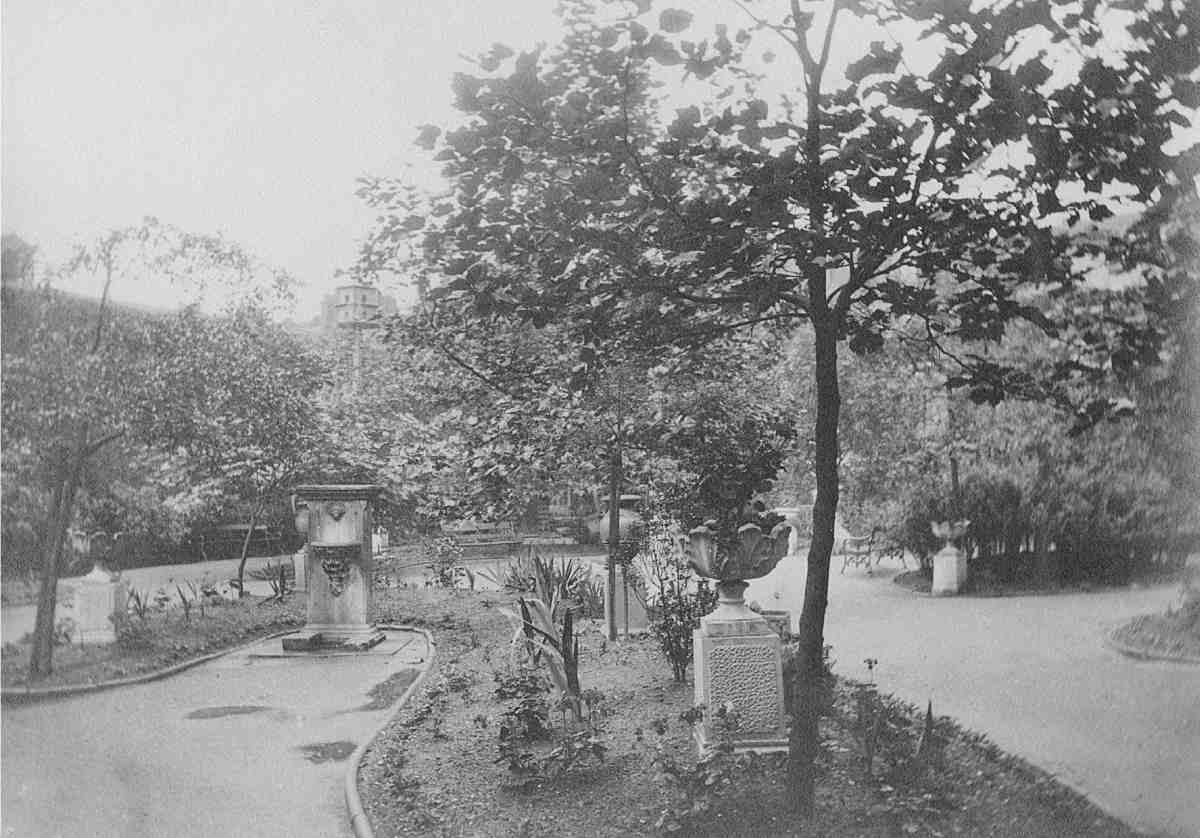

227. St John's Gardens, Benjamin Street, c. 1900

After this the site was neglected, partly used as a rubbish tip, and encroached on by workshops. (fn. 122) In the mid-1860s the Holborn District Medical Officer of Health urged that this and two other disused burial grounds in the Holborn area be turned into parks, to allure persons of 'sedentary occupations' from their dark courts and alleys, to take air and exercise. (fn. 123) It took considerable effort on the part of the parish and rector of St John to reestablish their title to the ground, and thanks to money given by an anonymous benefactor in about 1885 the site was laid out as an ornamental public garden, with trees, flower-beds and a dovecote, designed by J. Forsyth Johnson, honorary landscape gardener to the Metropolitan Public Gardens Association (Ill. 227). A decorative stone drinking fountain, now in poor condition, probably dates from this time. (fn. 124)

In 1904 responsibility for management was transferred from the parish to the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. (fn. 125) The garden remained secluded until the 1960s when it assumed almost its present dimensions, absorbing the sites of demolished houses in Benjamin and Britton Streets. A further strip of ground was given in the 1970s by the architects YRM, who were building their new offices adjoining on part of the former Booth's distillery site (Ill. 210).