Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Originally published by London County Council, London, 2008.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Clerkenwell Close area: Introduction; St Mary's nunnery site', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp28-39 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Clerkenwell Close area: Introduction; St Mary's nunnery site', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Edited by Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp28-39.

"Clerkenwell Close area: Introduction; St Mary's nunnery site". Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell. Ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp28-39.

In this section

CHAPTER I

Clerkenwell Close Area

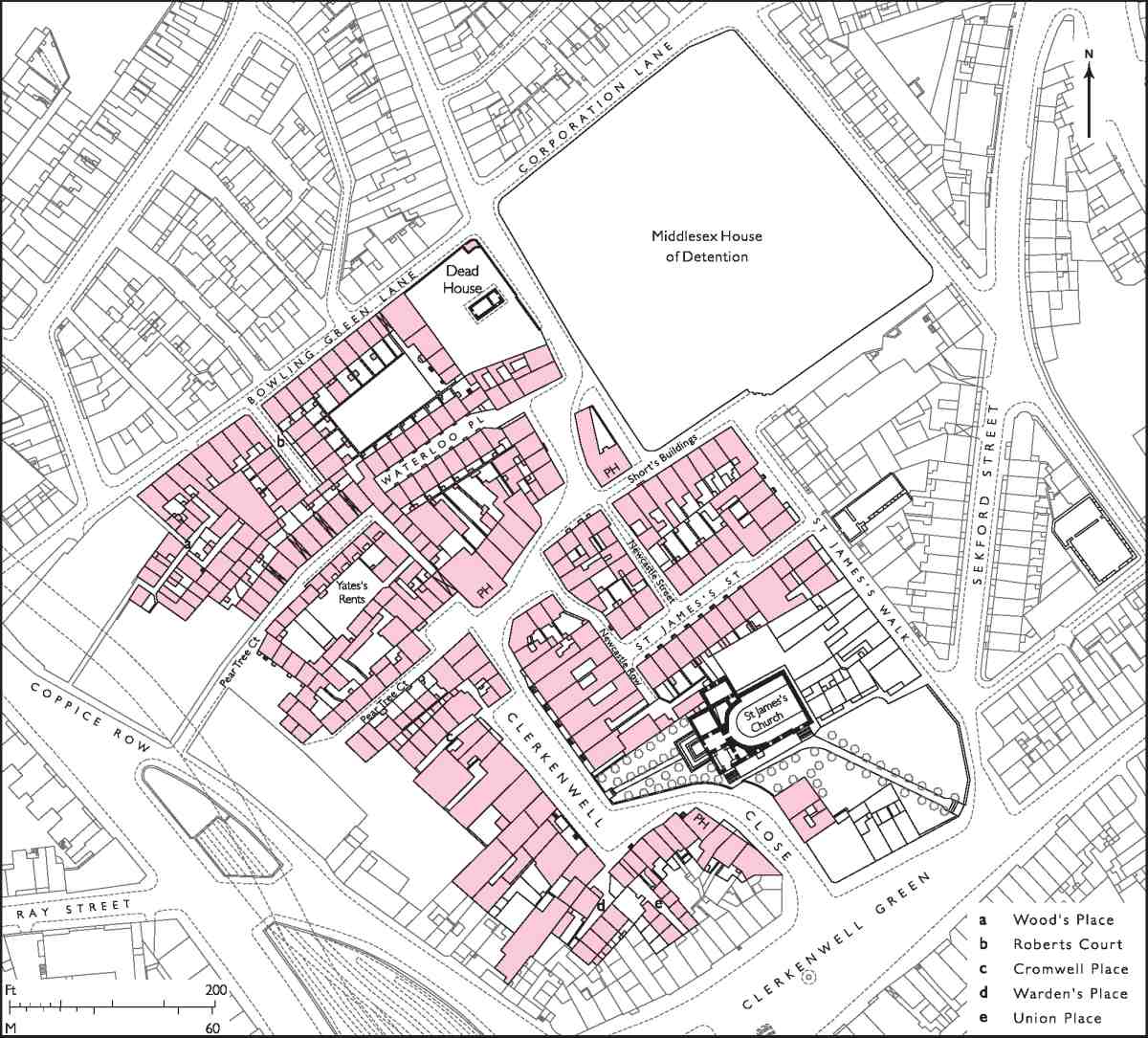

5. Clerkenwell Close area

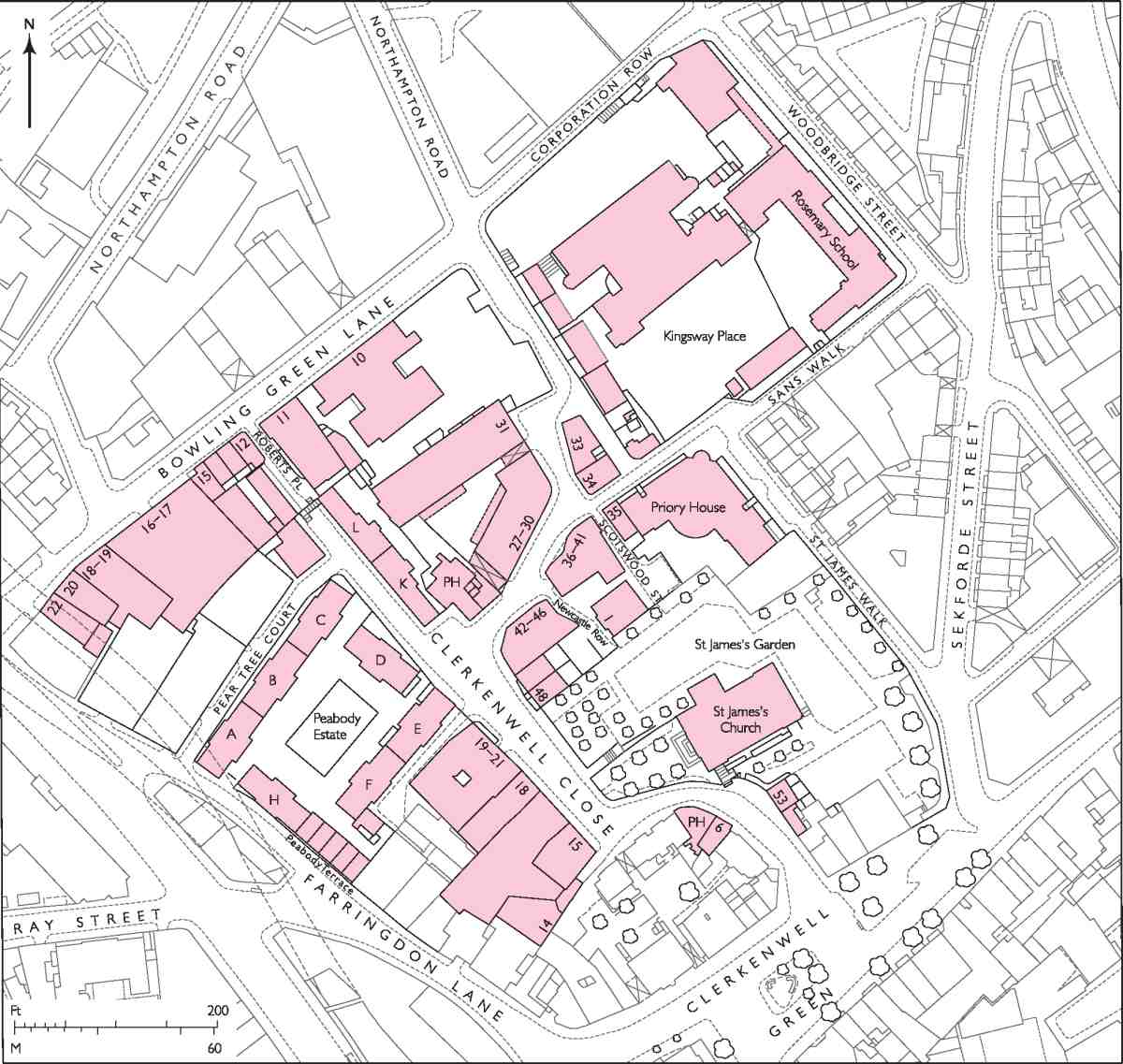

This chapter describes the historic district around Clerkenwell Close, the greater part of which made up the precinct of the medieval nunnery of St Mary. The area, bounded on the south by properties along the north side of Clerkenwell Green and on the north by Bowling Green Lane and Corporation Row, extends west from St James's Walk and Woodbridge Street as far as Farringdon Lane (Ill. 5). At its heart are the parish church of St James—a solid Georgian preaching box with a Gibbsian steeple, which replaced the conventual church in 1788–92—and the Close itself, winding picturesquely around the churchyard.

Outside the precinct, the site of the former Hugh Myddelton School and probably also the south side of Bowling Green Lane were parts of the fields belonging to the nunnery. After the Dissolution these followed separate descents, the former as part of the estate of the Earls (later Marquesses) of Northampton. (The north side of Bowling Green Lane, also part of the Northampton estate, is described in volume xlvii of the Survey of London.)

The presence of the nunnery and church has greatly influenced the history and character of the area. Knights and courtiers found the precinct a desirable place to live before the Dissolution, and continued to do so afterwards, the Close boasting several mansions in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This status was not maintained. The ground in the north and east was taken for institutional buildings—prisons and a workhouse—and the former nunnery close itself became more densely built up, the large houses sub-divided or replaced by craftsmen's housing and workshops. However, the rebuilding of the church on the old site confirmed this area as the hub of the parish, and the architect of the new church, James Carr, was himself responsible for developing a number of good-class houses in the immediate vicinity, mostly occupied by master-craftsmen.

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the area of the Close remained an industrial centre, clock- and watchmaking latterly giving way to light engineering and printing. Some old slum courts and alleys on the west side were swept away in the 1870s and 80s and replaced by model dwellings. In Bowling Green Lane, poor housing gave way to commercial buildings, with some fine warehouses erected in the 1870s. The greatest change in the character of the area, however, came with the closure of the surviving prison, the Middlesex House of Detention, in the 1880s, and the building of two board schools (one on the prison site) and a central depot for the London School Board.

After the Second World War the area suffered from a long-standing and ultimately unsuccessful plan to demolish most of the Close for an enlarged open space, but a few houses survive, or have been rebuilt in facsimile, to augment the church and suggest something of the area's historic character. Recent redevelopment along the west side and elsewhere has been in the main respectful of the street's scale and character, if rather dull. In contrast is the 1980s office building at No. 40, an anomaly which somehow slipped through the planning net.

St Mary's Nunnery

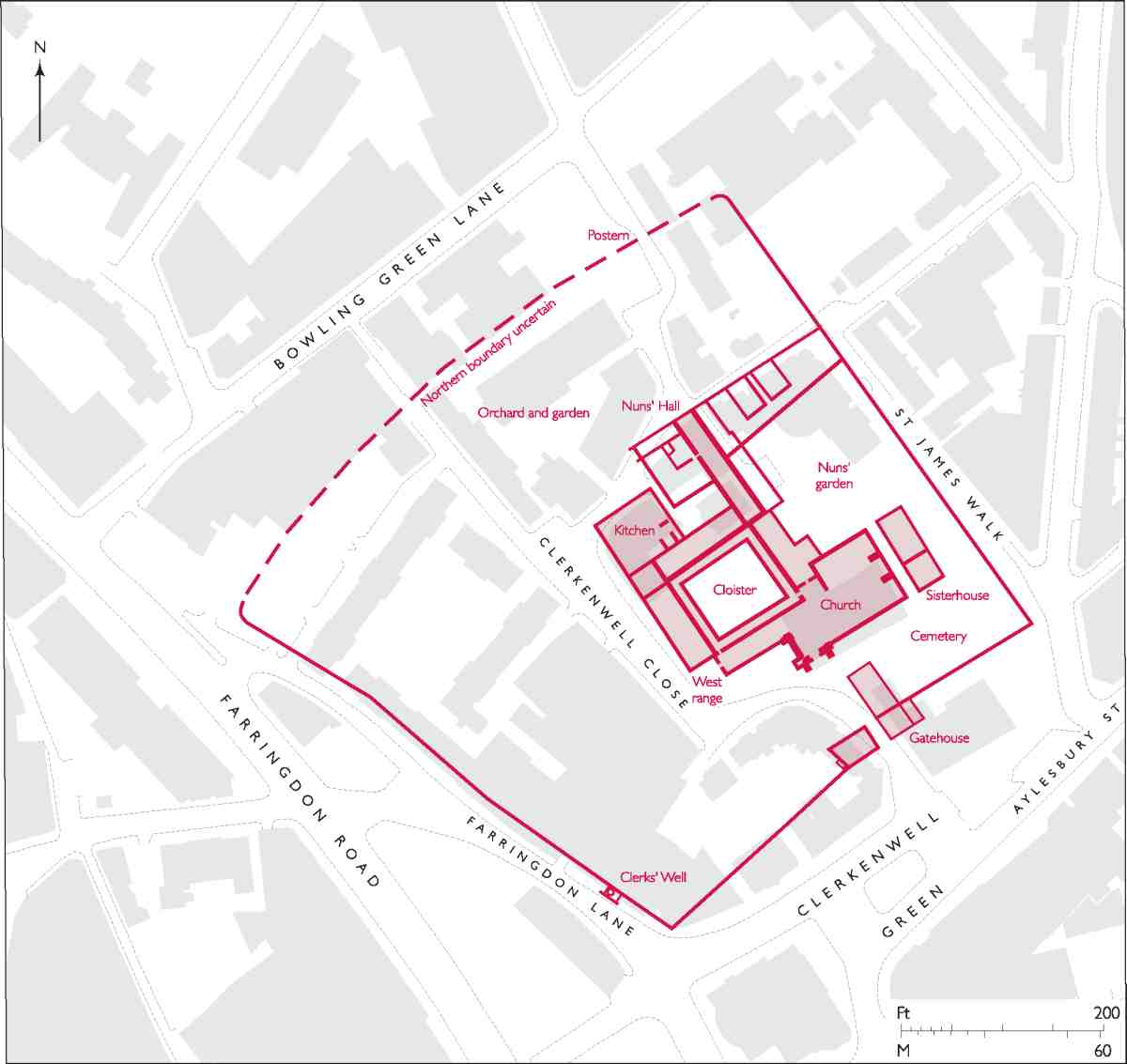

The nunnery of St Mary, a house of Augustinian canonesses, was founded shortly after the adjacent Hospitaller priory of St John in about 1144 by the same man, Jordan de Bricet, the lord of Clerkenwell manor (see also page 115). (fn. 1) It stood to the north of the priory, in a field next to the Clerks' Well, the boundaries of the precinct approximating to present-day Farringdon Lane, Clerkenwell Green, St James's Walk and on the north side, though this is not certain, the line now represented by the backs of the plots along the south side of Bowling Green Lane (Ill. 6). A private roadway on the line of present-day Aylesbury Street and Clerkenwell Green gave access from the main north—south roads. By 1160 a curia or wall had been built around the precinct, and further grants later in the century by Bricet and his family also gave the nuns fields and meadows to the north, either side of St John Street.

A stone church dedicated to St Mary, built c. 1160, was the first major structure; adjoining was a chapter-house, where Bricet and his wife were later buried. Elsewhere in the precinct, any residential or service buildings were probably of timber. The layout of the inner core of the convent was formalized in the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries when the church was enlarged and a cloister and other stone-built ranges erected to its north (Ill. 6). This expansion reflected the nunnery's prosperity at the time, the consolidation of its rights and privileges by a papal bull of the 1180s, and the creation of a new parish of Clerkenwell in 1176, with the nunnery church doubling as the parish church.

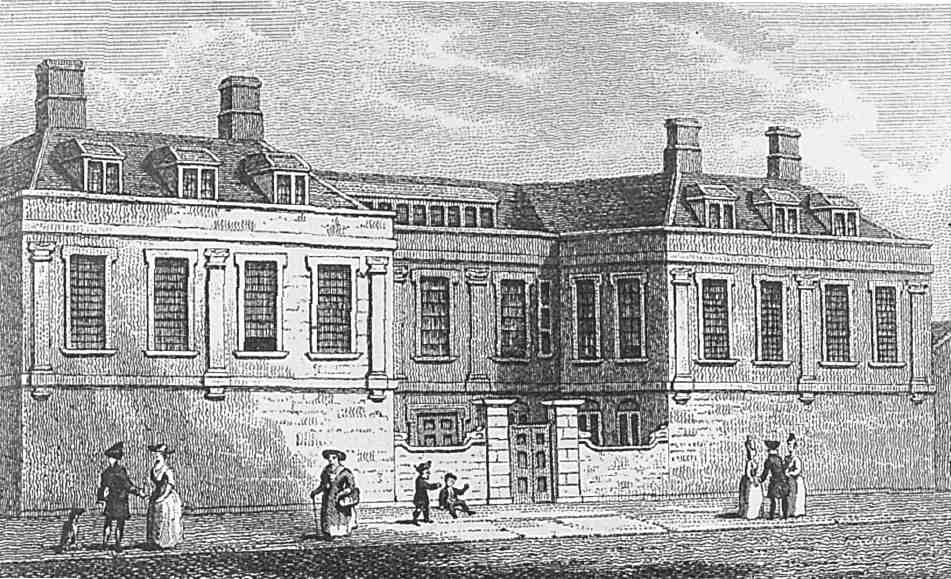

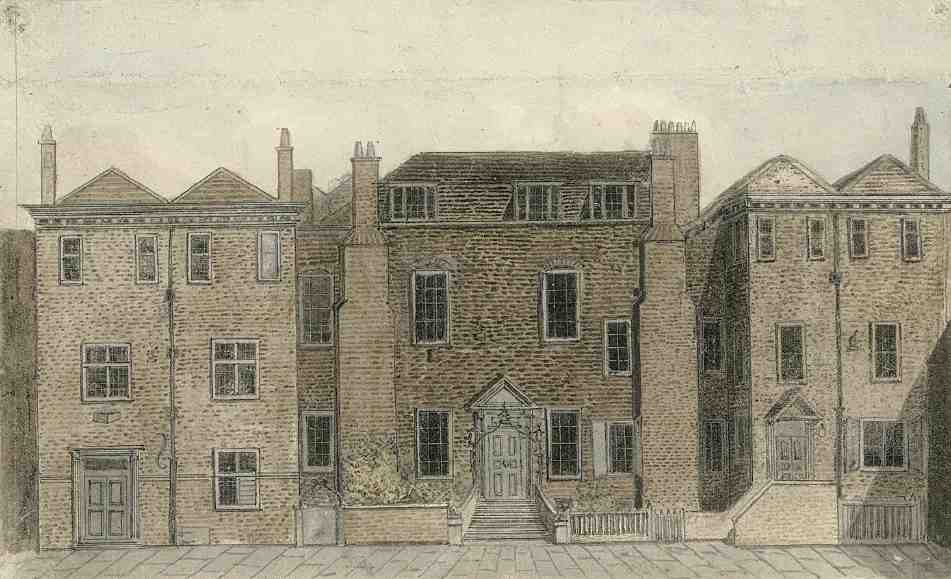

Among other new buildings at this time were a gatehouse, facing the Green, and, north of the church, ranged around the cloister, a series of apartments, including probably the prioress's lodging, dormitory, refectory and kitchen. Further north was a small service court, from which one building, with ragstone lower walls and Norman door arches, survived into the eighteenth century. Known by then as the 'Nuns' Hall', it was most likely built as a hall for guests (Ills 7, 8). There was also an infirmary with its own chapel, but its location is unknown.

6. St Mary's nunnery. The precinct and principal buildings in the early sixteenth century, superimposed on the modern street plan

Although this was a nunnery, the community within it was mixed. Records are intermittent, but there seem to have been seldom more than fifteen or so nuns at any one time. There were also male brethren and chaplains, and other officials, who must have had their own accommodation, and perhaps a discrete part of the church in which to worship. Despite its many endowments and land-holdings, for much of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries St Mary's was in financial difficulties. One source of extra income was the letting of tenements in the precinct to lay tenants or 'corrodians', which continued up to the Dissolution. As well as the corrodians, there were servants living in the precincts, and guests or boarders.

Significant changes were made to the principal buildings with the improvement of the nunnery finances from the late fifteenth century. Work began on a partial rebuilding of the church in the late 1470s and continued into the early 1500s, and as part of this the church and tower, and probably also the gatehouse, were given stone battlements (Ill. 22, and see Ill. 91 on page 87).

By the early sixteenth century rebuilding had extended to the cloister, the form of which is known from surviving fragments of the south wall (i.e. the nave north wall) and eighteenth-century views (Ills 27, 28). The cloister walk on the south side (and presumably elsewhere) had a tiled floor, outer walls of Kentish rubble divided into bays by limestone responds with triple shafts, an inner stone arcade, and brick vaulting with stone ribs and decorative bosses.

7. Remains of the Nuns' Hall in the 1780s, with workshop floors added by William and Richard Gomm

8. Detail of Norman doorway in the Nuns' Hall, c. 1780

9. Clerkenwell Close and vicinity in the 1670s

At this period about 12 per cent of income was from privately rented tenements within the precinct, which had attracted knights and courtiers as residents. Lay tenants of the early 1500s included the Ladies Burdall, Froginton, Stannop and Vere; and Sir Halnath Mauleverer, who had fought for Richard III at Bosworth Field. Mauleverer asked to be buried in the church and left money towards rebuilding the cloister. (fn. 2) At this time the nunnery was also boarding girls and gentlewomen, perhaps in a school.

10. Newcastle House, Clerkenwell Close, c. 1790, based on a drawing made by James Carr

After the Dissolution: mansions and courtiers

St Mary's was one of the last nunneries to be suppressed, in 1539, the nuns being given pensions by the King. By September of that year the walled precinct was in the hands of the Duke of Norfolk, a loyal servant to Henry VIII, though a few years later he returned it in exchange for property in south Lambeth. In 1545 the site was acquired by Walter Hendley, an attorney of the Court of Augmentations, and it then passed rapidly through a succession of owners. By February 1557 it was in the possession of Sir Thomas Pope, treasurer of the Court of Augmentations, who had been living there with his wife since 1547. (fn. 3)

The Augustinian tradition of leasing tenements to laymen made the transition from monastic precinct to secular suburb a relatively easy one. Many of the nunnery buildings were converted to form private mansions with spacious gardens (Ill. 9). Demolition within the core of the convent was restricted to the north choir 'aisle' (part of the nuns' choir) and the east range of the cloister, while the long-term survival of the church was effectively guaranteed by its parochial status.

The area of the Close continued to be favoured by the wealthy and powerful well into the seventeenth century, despite the building in 1615 of a prison immediately to the north. Of the several courtier's mansions here in the postDissolution period, the most important were Newcastle House and Challoner House, later known as Cromwell House, which faced each other across the Close (Ills 10, 11).

11. Challoner or Cromwell House, Clerkenwell Close, c. 1794

Architecturally, Newcastle House was the more distinguished. Named after William Cavendish, Earl and later 1st Duke of Newcastle, it stood on the east side of the Close, the entrance range occupying the site of the prioress's residence on the west side of the nuns' cloister. In the early 1600s this property was acquired and probably rebuilt by Sir Thomas Kitson and his wife Elizabeth, of Hengrave Hall, Suffolk. (fn. 4) Cavendish seems to have purchased the house from Lady Kitson (d. 1628) or her executors. He was in residence by 1630, when he wrote from Clerkenwell to the Earl of Strafford of his disillusionment with town life and his 'sometimes sweet dreames of the Countrye'. By April 1633 he had been given permission to erect a gallery in St James's Church for his family. (fn. 5)

The appearance of the house suggests that it was much rebuilt or at least refronted about this time (Ill. 10). Its disposition facing the street, with protruding side wings either side of a small entrance court, and its understated Classicism, were characteristic as much of town as country houses of the period. In particular, the order of short pilasters which accentuated the piano nobile was a feature that occurred in other architecturally fashionable houses of the 1630s and 40s—such as West Horsley Place, Surrey, and Stratfield Saye, Hampshire. Who designed the house is not known, though the names of John Smythson, Cavendish's architect at Bolsover Castle and Welbeck Abbey, or Smythson's son, Huntingdon, have been put forward. (fn. 6)

Behind the L-shaped house, the old cloister garth was laid out in a parterre, and beyond, stretching back to New Prison Walk, was a second, larger garden, on the site of the nuns' garden, laid out in symmetrical plots (Ill. 9). The house and grounds seem to have incorporated what remained of the cloisters, and presumably also the stables and coach-house where Lady Kitson had kept her best coach—perhaps in the so-called Nuns' Hall. (fn. 7)

A prominent royalist during the early years of the Civil Wars, Cavendish spent the Interregnum on the Continent, mostly in Antwerp. With funds short (his estates having been sequestered), his trustees sold the mansion in 1654 to Sir John Cropley, who resided there. (Cropley, who paid £1,400 for it, later claimed to have spent £7,000 in 'building thereon', but this seems unlikely.) Although an Act of Parliament restored most of the Newcastle estates in 1660, it took a further two years, a Chancery case and money raised from the sale of another estate to recover the house from Cropley. (fn. 8) The Duke and his eccentric Duchess— 'Mad Madge of Newcastle'—continued to reside and entertain at the house until their deaths in the 1670s. (fn. 9)

12. Old buildings at the corner of Pear Tree Court, looking south-west down Clerkenwell Close, 1880

An undated, seventeenth-century plan of a manège yard which may relate to Newcastle House shows a symmetrical structure, with suites of large, regular rooms, and a long yard behind, with posts and railings, and stabling for 24 horses. (fn. 10) One of the greatest horsemen and cavalrymen of his era, and a published authority on the subject, the Duke of Newcastle established riding schools at his houses at Welbeck and Bolsover, and also in Antwerp while in exile. The undated plan suggests that he may have been planning another school at Clerkenwell, perhaps along the lines of the riding academy for gentlemen founded in Paris in the 1590s by Antoine de Pluvinel, Louis XIII's riding instructor. (fn. 11)

Challoner House, the residence in the early 1600s of the courtier and chemist Sir Thomas Chaloner, or Challoner (d. 1615), was cut from coarser architectural cloth (Ill. 11). Its rather severe, old-fashioned central range, with chimneystacks rudely facing the street, appears to have had sixteenth-century or possibly even earlier origins. (It is not to be confused, however, with the house of Chaloner's stepfather of the same name, the diplomat and author, who died in 1565 at his Clerkenwell mansion, for this seems to have been in St John's precinct, not the old nunnery close.) (fn. 12) The earliest known occupant of Challoner House was Anthonie Sandes (or Sondes) of Throwley, Kent (d. 1571); his son, Sir Thomas (d. 1593), also resided there. The property came to Chaloner through his wife, Judith, whose first husband had acquired it in 1601. (fn. 13) The antiquarian John Weever, a resident of the Close, said in 1631 that Chaloner had built the house 'of late', perhaps referring to recent improvements. The side pavilion wings, for instance, with their hipped roofs, box cornicing, and mullioned and transomed windows, do look to have been added in the seventeenth century. (fn. 14)

Chaloner was a favourite of James I, and governor to the young Prince Henry. After his death the house had several prominent residents in the 1620s and 30s, including James, 1st Earl of Marlborough, the former Lord Treasurer, and Robert Kerr, 6th Earl of Somerset, another of James's favourites. (fn. 15) Its later name, Cromwell House, comes from an unlikely tradition that Oliver Cromwell resided here.

This tradition probably arose from the associations of this area, despite its royal connections, with republicans or republican sympathizers. During the mid-1600s Philip, 4th Baron Wharton, an intimate of Cromwell, was living in the Close, as was the Parliamentarian Josias Berners, solicitor to the New River Company, an associate of the Chaloner family. Two of Sir Thomas Chaloner's sons, James and Thomas, were regicides. (fn. 16)

13. Nos 36–41 Clerkenwell Close, shortly before demolition in 1910

Other seventeenth-century residents of the Close included Sir Anthony Palmer, Knight of the Bath, who had a house immediately to the south of Challoner House in the 1610s; Daniel Hough, a City alderman, who in the 1650s–80s resided in a mansion near the prison, later owned by the Short family; Dr Theophilus Garencières, French physician, author and first translator into English of Nostradamus; and Dr Everard Maynwaring, 'doctor in physic and hermetick phylosophy', author. Both Garencières and Maynwaring were living here in the 1660s and 70s. (fn. 17)

By this time, Clerkenwell Close was probably losing its status somewhat. Infilling and building development on some of the old gardens in the precinct is evident on Ogilby & Morgan's survey of 1676 (Ill. 9). Dense courts and alleys were already in the making, for instance in Breeches Yard, where the land sloped away towards the Fleet. This later became part of an interlinked group of courts known variously as Pear Tree Court or Cheslyn's Rents; more houses were added here in the 1690s (Ill. 12). (fn. 18) By 1710 Cromwell House had been divided in three, and acquired by a brewer, Andrew Crosse, who lived in the central part till his death in the 1740s. (fn. 19) Crosse was typical of the new class of merchants and tradesmen that came to populate the Close in the eighteenth century. The last aristocratic resident was Elizabeth, the widowed Duchess of Albemarle, eldest daughter of the 2nd Duke of Newcastle, who lived at Newcastle House until her death in 1734. The 'Mad Duchess' had been unhinged for some time, and after her first husband's death apparently refused to marry any but a crown prince. Ralph, Earl of Montagu, is said to have won her hand by masquerading as the Emperor of China. (fn. 20)

Newcastle House then stood empty until 1736, when it was leased to a cabinet-maker and upholsterer, William Gomm, and from then until its demolition in the early 1790s was occupied by a succession of furniture-makers. Gomm himself lived there until 1747, when he moved to Cromwell House, and Newcastle House became the residence of his elder son and partner, Richard. Although occupying different buildings in the Close—and William seems to have had a separate workshop at Cromwell House—they used the Newcastle House address for their trade labels. It was later claimed that the partnership had spent 'upwards' of £5,000 on additional buildings, including 'the most compleat & extensive Suit of Ware-rooms in London'. (fn. 21) These were housed in a wooden range with a continuous north-facing run of windows, constructed over the surviving south cloister. Wider than the cloister walk itself, this was partly carried on a new wooden arcade, parallel to the original. Though the upper floor was plain, some care was taken to give the arcade a Gothic appearance so as to blend in with the medieval stonework, and a decorative 'Gothick' screen was erected at the east end of the old cloister walk (Ill. 28). The firm's main workshops were to the north of the house, in a double range built over the remains of the Nuns' Hall (Ill. 7).

Artisans' Housing in and around the Close. James Carr, architect, 1790s. Mostly demolished

14. Nos 45–46 and 47–52 Clerkenwell Close (formerly Newcastle Place) in 1943

15. Nos 3–5 St James's Row (formerly Street) in 1943

16. Looking down Newcastle Row towards St James's Church, in 1951; No. 42 Clerkenwell Close on the right

17. Nos 47–52 Clerkenwell Close (formerly 1–6 Newcastle Place), elevation and typical floor plans in 1956. Nos 49–52 demolished

The Gomms' occupation of Newcastle House terminated with their bankruptcy in 1776. Their lease and assets were bought at auction by their one-time partner, Peter Francis Mallet of Clerkenwell Green, (fn. 22) who installed himself in the house, and presumably used the workshops and showrooms for his own business. In June 1790 the cabinet-makers Francis Gilding and Francis Banner took over the building, and Mallet's stock of timber, while their Aldersgate Street premises were being rebuilt after a fire, Gilding himself residing in the house. (fn. 23) They made furniture for the new parish church about this time (see page 50).

Other old mansions in the Close fell to redevelopment in the course of the eighteenth century. The Short family demolished their old house, now inconveniently close to two prisons, and in 1746 leased its site to John Pescod, a Clerkenwell carpenter, to build fifteen brick houses in a short east—west street, called Short's Buildings. (fn. 24) There was some further building in the early 1780s, when Joseph Brayne of Rosoman Street and his son George, mason and carpenter respectively, built a short row of artisans' houses and workshops on part of the old Nuns' Hall site (latterly Nos 36–41 Clerkenwell Close, see Ill. 13). (fn. 25) The redevelopment of Newcastle House followed a few years later.

Newcastle House redevelopment

The rebuilding of the parish church of St James to the designs of James Carr in 1788–92 prompted extensive new building in the vicinity, initiated by Carr himself, who in the early 1790s contracted to buy the freehold of Newcastle House from the 2nd Duke's heirs for £2,500. Carr pulled down the greater part of the house in 1792, converting the 'material thereof to his own use'. (fn. 26)

Of the forty-odd houses built here to Carr's designs, only two survive—the present Nos 47 and 48 Clerkenwell Close (Ill. 65). They were the northernmost pair in a six-house terrace known until 1939 as Newcastle Place (Ills 14, 17). Behind, on the former garden of Newcastle House, Carr laid out a short street of some twenty sub stantial houses called St James's Street (later Row) opening into St James's Walk, where he built a further seven houses, flanking the entrance to the new street. The rest of the development comprised groups of smaller houses in Clerkenwell Close (latterly Nos 42–46), where it curves round to the north-east, and in the streets now called Newcastle Row and Scotswood Street. A small part of the site immediately south of the old house was given up to extend the churchyard. (fn. 27)

Carr was associated in the development with James Fisher, a Bunhill Row carpenter, who presumably was involved in the building process; Carr's daughter Elizabeth married Fisher's son. (fn. 28) Houses on the south side of St James's Street and Walk descended to Carr's surveyor son Henry, but the rest of the estate remained with the Carr-Fisher descendants until it was broken up and sold at auction in 1881. (fn. 29)

Standing where Newcastle House itself had stood, Newcastle Place was the most prominent part of Carr's development, and the house fronts had slightly more architectural detailing than the rest—principally a brick band-course between the ground and first floors, and relieving arches over the first-floor windows (Ills 14, 17), an early example of this treatment, adopted about this time by C. R. Cockerell in his designs for Northampton Square (see page 304). All six houses were occupied by 1797, Carr himself residing at No. 6, next to the church, from 1794 to 1802. Another early occupant, from 1795 until c. 1823, was the Rev. John Moore at No. 5. Others included businessmen: at No. 3, a merchant, James (or Jacques) Le Jeune, and at No. 2 (the present No. 48) a watchmaker, Edward French (d. 1822), one of whose watches is preserved in the Clockmakers' Museum at the Guildhall. Before long the back gardens were being sacrificed for workshops: by 1808 French had built a small workshop behind No. 2, while at No. 6 Carr's successor, Edward Cherrell, another watchmaker, had covered most of his garden with a two-storey workshop. (fn. 30)

Most of the houses had, from the start, continuous workshop windows in the garrets (Ills 14–17), the main exception being the terrace on the north side of St James's Street. The houses were occupied well into the nineteenth century typically by artisans and craftsmen, many of them in the clock, watch and jewellery trades. (fn. 31)

John Moore & Sons' clock factory (demolished)

Clerkenwell Close was for long a centre of the clock and watch trades, carried on mostly in small workshops where only one aspect of production might be undertaken. A complete clock factory, run by John Moore & Sons, was set up in two old houses belonging to the Vestry beside the parochial burial ground in Bowling Green Lane, at Nos 38 and 39 (later 32) Clerkenwell Close.

18. John Moore & Sons' clock factory, Nos 38–39 Clerkenwell Close, c. 1852. Demolished

The business began in the 1790s with Benjamin Handley, a clockmaker at No. 38, who by 1801 had entered into partnership with John Moore; the latter was the sole proprietor by 1820. In 1824 Moore took a new 31–year lease from the Vestry, and was given permission to convert the two buildings into one. A plan of 1833 shows the eastern house with a counting-house and store on the ground floor, and a rear workshop with long window lights; the other, older house, with a central chimney stack, had a similar rear workshop. Illustration 18 perhaps gives an exaggerated impression of the scale of the premises, in reality fairly small (Ill. 19). (fn. 32) Moores made bracket, longcase and musical clocks for domestic use, and church, turret and other public clocks. A chiming clock with a nine-foot dial was made by them in 1819 for Lima Cathedral. Most aspects of clock production were carried on in-house, with a high degree of mechanization for activities such as cutting, sharpening and polishing. Much of the finishing work, however, was done by hand. By 1858 the firm was employing 30 to 40 men.

Moores moved from Clerkenwell Close c. 1900 to Spencer Street, where they carried on for twenty years, mostly as watchmakers. The old factory became an annexe to the School Board stores adjoining, the site later being subsumed into that of the Bowling Green Lane School playground.

19. View south down Clerkenwell Close from Rosoman Street in 1938; former Moores clock factory to right

The area since the late nineteenth century

By the 1870s, aside from the church and prison sites, the area between Bowling Green Lane and Clerkenwell Green had become thickly built up with housing and workshops (Ill. 20). On the west side of the Close a few of the older, larger houses remained, some still private residences, others given over to industry. Elsewhere on this side infilling and redevelopment had created a denser, meaner topography, with shabby side streets and alleys supporting an increasingly poor population. At the southern end, Union Place, a court of some half-a-dozen tiny properties, had been squeezed in behind Nos 6 and 7. Near by was another court, Warden's Place, in existence by the early eighteenth century. (fn. 33) Further north was Waterloo Place, a cul-de-sac of sixteen small houses, built on the site of one of the wings of Challoner House. The worst conditions were in the warren of Pear Tree Court and Yates's Rents. Here some of the fabric dated back to Elizabethan times, with numerous houses, 'dark, squeezed up, wavy in their outline, and depressed about the roof, like crushed hats' (Ill. 12). (fn. 34) Most of the buildings were very small and, with an average of about ten people to each, crowded. Residents were generally of the poorest class—costermongers, laundresses, general labourers. Sanitation was rudimentary, and though the major landlord, John Earley Cook, employed his own doctor and missionary to look after his tenants, the mortality rate here was almost twice that for the parish as a whole. As John Hollingshead, author of Ragged London, noted in 1861, Cook, despite his claims to have the best interests of his tenants at heart, 'neither ventilates the rooms nor enlarges the stifling yards. A little more cleanliness might help the missionary, and would certainly lessen the doctor's work'. (fn. 35)

There were other signs of social degradation. At No. 12 (the site of the present No. 18) was a mission house, established by the philanthropist John Groom. Near by at No. 10 was the Clerkenwell Casual Poor Ward. At No. 31 was a licensed lodging-house kept under police surveillance, the local vicar having complained of it as a 'resort of thieves, prostitutes and criminals of every class'. (fn. 36)

Within little more than a decade redevelopment had dramatically altered the character of this west side of the Close; by and large the more orderly street and building pattern that resulted is the one existing today (Ill. 5). The Pear Tree Court area was cleared by the Metropolitan Board of Works and Peabody Dwellings erected. Immediately to the south, new stables, factories and warehouses began to replace most of the old houses at Nos 8–15 (now 14–21), bringing new businesses, such as printing and machine-making. (fn. 37) To the north, in Bowling Green Lane, most of the houses on the south side were demolished for warehouses, and the site of the burial ground and mortuary on the corner of the Close taken for a board school.

This process of change continued in the 1890s with the building of the Hugh Myddelton School on the site of the prison, closely followed by the demolition of more houses on the west side of the Close, including Waterloo Place, for the School Board's own warehouses, giving a municipal character to the north end of the Close.

From the early 1900s until the 1950s the Close retained its mixture of mostly poor tenanted houses and workshops, newer manufacturing premises and school buildings. A little demolition took place, as at Nos 36–41 (Ill. 13), pulled down in 1910 by Finsbury Borough Council to widen the roadway. (fn. 38) With the London County Council's plan in the 1950s to demolish most of the Close and buildings on the north side of Clerkenwell Green for an enlarged public open space around the church the fabric was allowed to deteriorate badly (see also page 95). Some buildings were pulled down, including Nos 9–13 in the Close, and the whole of St James's Row. Any reinvestment or redevelopment was held in abeyance while the scheme rumbled on, latterly in combination with another to extend the Hugh Myddelton School, and by the late 1960s many of the remaining houses and workshops were condemned and rotting.

The open space and school enlargement schemes were finally scrapped, and in 1969 the Close was included as part of the Clerkenwell Green Conservation Area. The clearance site to the north of the church was used to extend the churchyard as a public garden, called St James's Garden. Since then the few surviving old houses have been restored, and there has been some commercial and residential redevelopment, particularly in the 1980s and 90s.

20. Clerkenwell Close area in the 1870s

The following account of the buildings in and around Clerkenwell Close begins with the parish church, the most important historic monument in the area, and its medieval predecessor. It continues with the history of the large site on the east side of the Close, bounded by Sans Walk, Woodbridge Street and Corporation Row, occupied since the early seventeenth century by a succession of institutional buildings: prisons, workhouses and schools. This is followed by a description of the Peabody Estate in and around Pear Tree Court, and the chapter concludes with an inventory of other buildings in the Close and on the south side of Bowling Green Lane.