A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Introduction: Cricklade and Environs', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18, ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/1-12 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Introduction: Cricklade and Environs', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Edited by Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/1-12.

"Introduction: Cricklade and Environs". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/1-12.

In this section

CRICKLADE AND ENVIRONS

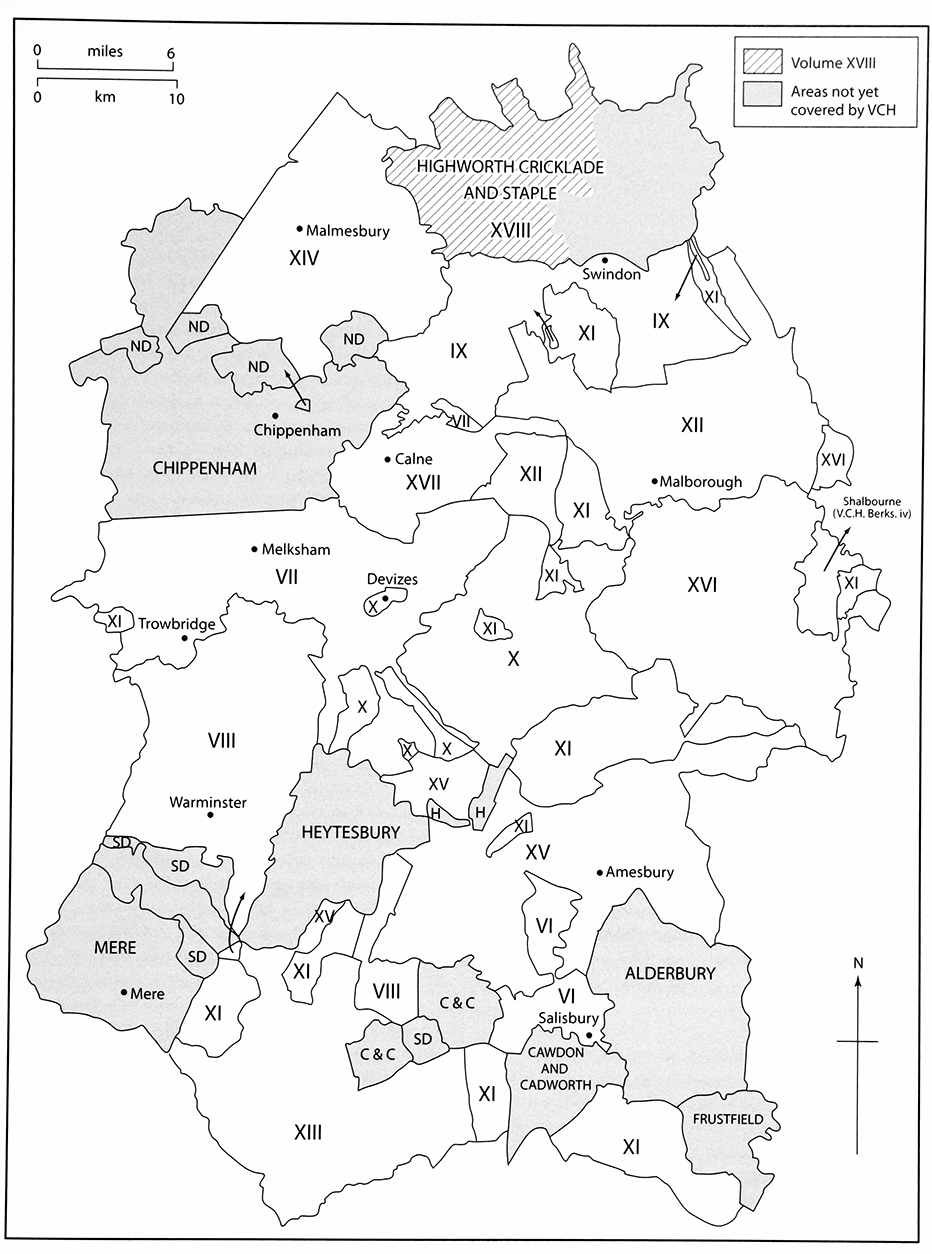

MAP. 1. Key to volumes published in this series.

THIS VOLUME offers histories of a block of nine contiguous civil parishes and their predecessors in northern Wiltshire, which approximated to the western half of the medieval hundred of Highworth. (fn. 1) Together they comprise some 11,700 ha of the Wiltshire claylands and upper Thames valley, adjoining Gloucestershire to the north and Swindon to the east. The demarcation of administrative boundaries and territories across this land is more than usually complicated. The jagged county boundary with Gloucestershire suggests compromise and conflict. Marston Meysey, alone of modern Wiltshire civil parishes, lies wholly north of the Thames, and juts deep into Gloucestershire. Until the 19th century it was a chapelry of its neighbour Meysey Hampton (Glos.) and in consequence lay in Worcester and, from 1542, Gloucester diocese. Minety was a Gloucestershire ancient parish until transferred to Wiltshire in 1844, but always encircled a small Wiltshire enclave which included the parish church; consequently it was in Salisbury diocese until 1837. Its northern neighbours, Kemble, Poole Keynes, Shorncote and Somerford Keynes, were ancient Wiltshire parishes transferred to Gloucestershire in 1896. (fn. 2) Their histories are reserved for treatment in a future volume of the VCH Gloucestershire series.

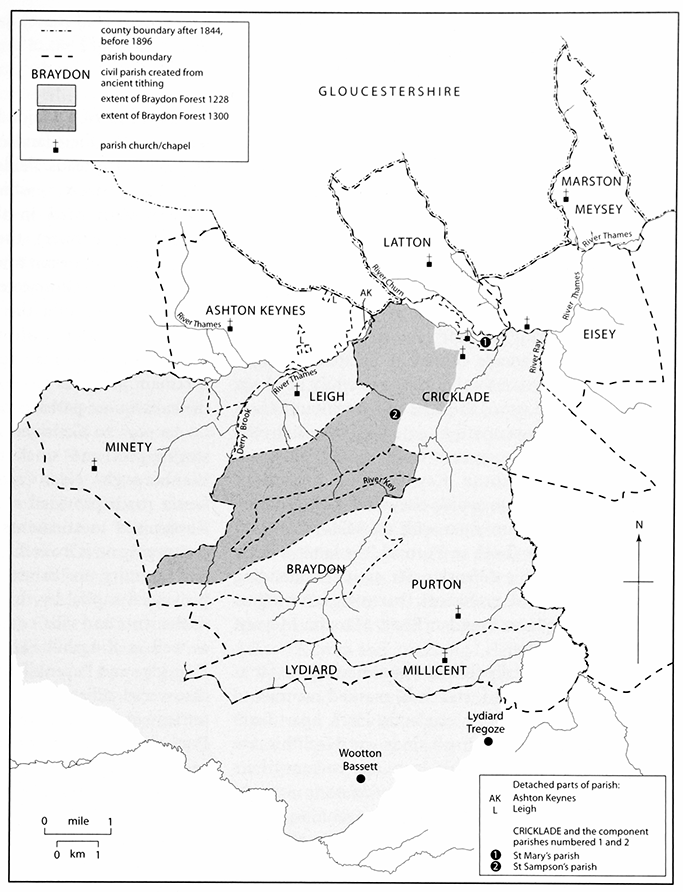

Two civil parishes included in this volume, Braydon and Leigh, were tithings of Purton and Ashton Keynes ancient parishes respectively. Leigh, an ancient chapelry, is treated separately from its mother parish, while Braydon, whose chapel dated only from 1868 and was closed in 1970, is treated as a section of the history of Purton. Eisey ancient parish, with its chapelry Water Eaton, was transferred to Latton civil parish in 1896. Cricklade was divided between two ecclesiastical parishes, St Sampson's and St Mary's, the former with a dependent chapelry at Widhill. The parishes united in 1899 and Widhill was transferred in 1934 to Blunsdon St Andrew (now Swindon). Onethird of Lydiard Millicent was taken by Swindon in 1980 to accommodate part of the town's western expansion. The medieval hundredal arrangements, described below, were similarly convoluted. Everywhere studied in this volume has altered its boundary, allegiance, or both.

Within this land Cricklade is the only town, and, despite its significance as Anglo-Saxon burh and parliamentary borough, is urban at only the slightest level; its population barely exceeds 4,000. Purton, its southern neighbour, is almost as populous and, with Lydiard Millicent, the three parishes account for over 70 per cent of the region's total of 13,400. To the west of these settlements lies the former Braydon forest, a remote country still, where few people live. Beyond the area of study three towns of very different character have influenced it. To the west the small hilltop town of Malmesbury provides a range of shops, services and employment, but on a much smaller scale than Cirencester (Glos.) to the north, which is the principal market centre for the southern Cotswolds and upper Thames valley. Cirencester in turn is dwarfed by Swindon, a major conurbation with a population in excess of 200,000, whose western and north-western suburbs nudge the eastern boundaries of Cricklade, Purton and Lydiard Millicent.

Swindon dominates the economic and, to a lesser extent, the social life of the area's inhabitants, although it takes no part in their local government. In return the countryside and leisure opportunities afforded by the area provide an amenity enjoyed by Swindon's population. Railway stations at Swindon and Chippenham; the M4 motorway, with a junction some 2 km from Lydiard Millicent; and the A419 trunk road by-passing Cricklade and Latton, all offer fast and easy communication with the rest of southern England, London and the midlands.

LANDSCAPE

The clay vale of north Wiltshire, on which all the parishes covered in this volume impinge, is bordered by outcrops of older rocks of the Great Oolite group to the north-west, and the younger Corallian beds to the south-east. (fn. 3) Of these older rocks only a small area of Cornbrash outcrops at the northern tip of Marston Meysey. The vale, composed of Kellaways and Oxford clays, has produced an undulating, poorly drained landscape, typically c. 100m above sea level, but rising to 134m at Ravensroost, the western limit of Braydon parish, and falling to below 80 m. around Cricklade. Much of this clayland lay within the medieval Braydon forest or its purlieus; it was managed as woodland and wood-pasture until the 17th century, and thereafter as enclosed dairy pasture with woodland compartments. Its poor soils make for unrewarding arable cultivation. The clay has been exploited for brickmaking at Purton and Lydiard Millicent, and for pottery manufacture at Minety and Ashton Keynes. Flat and monotonous in places, these extensive claylands have nevertheless formed ridges and modest hills, such as that on which Eisey church was built, and Bury hill in Purton, an Iron Age hillfort.

MAP 2. Parishes of the study area c. 1885 on a map of c. 1828 and showing the landscape character of the area and the contrast between the topography of Thames-side and forest parishes.

By contrast, the younger Corallian beds outcrop in the south-east of the area as a prominent limestone ridge, rising to 146 m. near Restrop in Purton, and typically around 130 m. across much of the settled parts of Purton and Lydiard Millicent parishes. This geological formation, which can be traced as an intermittent ridge trending north-east across Wiltshire from the Westbury area to Highworth, consists of Calcareous sands and a harder coral or oolitic limestone known as coral-rag. This ragstone, which is responsible for the prominent escarpment from which Pavenhill and Ringsbury look west across Braydon, provides a good coarse building stone, quarried at Purton and elsewhere, and widely used across the whole area, giving a character distinct from the adjoining Cotswold belt to the local vernacular architecture. In a few places – at Common Platt in Purton, and Lydiard Plain and Shaw in Lydiard Millicent – a younger clay deposit overlies the Corallian. This is Kimmeridge clay, which predominates further east around Swindon, and which was exploited by Roman potters on Shaw Ridge.

MAP 3. Parishes of the study area c. 1885, overlaid on the area subject to forest law in 1228 and in 1300. Before 1844 Minety parish was in Gloucestershire, except for a small area round the church.

Lydiard Plain forms an insignificant watershed between the river systems of the Bristol Avon, to the west, and the Thames to the north and east. Woodbridge brook, a tributary of the Avon, drains the south-west corner of the area, but all the others rivers and streams, principally the Swill brook and Derry brook, and rivers Key and Ray, flow east and northwards to the Thames. The river Churn, flowing from the north-west, passes Latton to join the Thames at Cricklade. Along with the clay vale and the Corallian ridge, therefore, the upper Thames valley is the third significant landscape component of the region under scrutiny. The river flows across the Oxford clay and falls from 88 m., where it enters Wiltshire at Ashton Keynes, to 75 m. at Marston Meysey. In its valley the clay has been mantled, as a result of glacial mudflows and meltwaters, by successive superficial deposits of gravels and alluvium. The gravel terraces have been massively exploited since the 1970s for aggregate and other construction manufactures, and the resulting extraction pits have filled with water. The Cotswold Water Park, a chain of shallow polygonal lakes divided by baulks and access roads, has created around Ashton Keynes and Latton, and their Gloucestershire neighbours, a landscape not dissimilar to that of the Norfolk Broads, and with the same potential for leisure pursuits and wildlife. Past and present courses of the Thames and its tributaries, which in several places are followed by the county and parish boundaries, have in consequence become hard to identify.

EARLY SETTLEMENT

PREHISTORY

Sophisticated archaeological investigation and monitoring ahead of gravel extraction and road improvements have greatly enhanced knowledge of prehistoric settlement and land use in the upper Thames valley since c. 1970. Farm complexes of the early or middle Iron Age periods have been identified at Eisey and Marston Meysey, while at Latton and Ashton Down (in Ashton Keynes) late Neolithic or early Bronze Age antecedents existed. A fluctuating mixed farming economy continuing over millennia has been demonstrated at Latton, and here and at various sites in Ashton Keynes occupation extended through the Roman period. The riverine Iron Age settlement at Cleveland farm, Ashton Keynes, may have been comparable in status to oppida elsewhere in the Thames valley, and perhaps on a par with the hillforts at Bury hill and Ringsbury (both in Purton), the latter a likely re-use of a Neolithic defensive site on a commanding hilltop. Evidence of prehistoric barrows surviving as ring ditches has been found at Eisey, Marston Meysey, Leigh and elsewhere.

The archaeologically fecund Thames valley, so far as prehistory is concerned, stands in marked contrast to the largely sterile Braydon claylands. Here, apart from Bury hill, only isolated small finds – a Neolithic axe from Lydiard Plain, possible Iron Age currency bars from Upper Minety – testify to prehistoric activity. While this doubtless reflects the lower value to settled Bronze and Iron age farming economies of dense woodland growing on poor soils, it must also be a consequence of archaeological bias towards studying river gravel sites.

THE ROMANO-BRITISH PERIOD

At Cleveland farm and other sites in Ashton Keynes the impact of the Roman conquest may have been delayed, its farming communities adapting gradually to the new administration and other changing circumstances. For the native Iron Age farmers of Latton, however, the construction of a major Roman supply route, Ermin Street, across their landscape was more disruptive, so that new farmsteads, fields and trackways were created.

Ermin Street, which branched from the London–Bath road in the Kennet valley at Speen (Berks.) to connect the Roman capital with the strategically important towns of Corinium (Cirencester) and Glevum (Gloucester), was built by military engineers soon after the conquest. It continued as a significant artery of trade and administration throughout the Roman period and beyond; stretches of it remain in use as fast motor roads. Its line traversed the subsequent parishes of Cricklade, Eisey and Latton on its way to Corinium from the Roman mansio or staging-post and small town of Durocornovium (in Wanborough). Near Cricklade it crossed the Thames. Lesser roads provided access from Roman and native Romanised settlements, such as the trackway converging on it from the east at Seven Bridges in Eisey.

Proximity to Ermin Street and Corinium – a provincial capital by the 4th century – attracted new settlements and villa complexes to the area. In Latton, as well as Kingshill Farm in Cricklade, and between Dogridge and Pavenhill in Purton, villa sites have been discovered adjacent to, or associated with, Roman settlements. The wealth of the late-Roman villa at Purton is suggested by the presence nearby of a walled cemetery which yielded opulent grave goods, and an apparently Christian interment. Evidence of Roman buildings has been found elsewhere in Purton parish, and at various locations within or close to the later town of Cricklade. The Purton villa may have superseded an earlier industrial complex on the same site, which produced pottery from at least four kilns during the 2nd century. Suitable clay and abundant wood for firing attracted potters not only to Purton, but especially several locations along Shaw Ridge (formerly in Lydiard Millicent and Lydiard Tregoze, now Swindon), from where they supplied the local market centre at Durocornovium. Brick and tile were also manufactured here, and at kilns in Minety parish.

THE MEDIEVAL PATTERN

ANGLO-SAXON FOUNDATIONS

The departure of the Romans after 400 AD did not, any more than their arrival, signify a clean break in the settlement history of the area. The archaeological sequence at the Kingshill Farm settlement suggests continuity into the early or mid Anglo-Saxon period; Cleveland farm continued in use until at least c. 500; and nearby at Ashton Down, which straddled the border between Ashton Keynes and Shorncote (Glos.), two burials and rebuilding work at the Roman farmstead probably occurred during the 7th century. Here the excavators found no evidence of Saxon domestic occupation, however, and concluded that the relict Roman landscape was being farmed from elsewhere, perhaps Somerford Keynes (Glos.). (fn. 4) At Purton a similar shift may have taken place, from the late-Roman settlement in the Dogridge area to a site some 2 km. further east, where a pagan AngloSaxon cemetery has been discovered.

Endowments of land to the newly founded Malmesbury abbey help to establish the pattern of landholding in the mid Anglo-Saxon period. Three grants in particular may corroborate the archaeological evidence: a 40-hide estate at Somerford Keynes, granted in 685; a 30-hide estate at Purton, granted in 688; and a 100-hide estate to the east of Braydon wood, granted away in an exchange purportedly of 688 (but probably later). (fn. 5) This, which may refer to Chelworth as the nucleus of a large territory corresponding to the later parish or hundred of Cricklade, is a possible successor to the Kingshill farm settlement.

Apart from Latton and Marston Meysey, all the later parishes studied here were the subject of 9th-century or earlier grants. Five-hide estates at Minety and Eisey went respectively to Malmesbury abbey in 844 and the bishop of Worcester in 855. Lydiard Millicent, a tenhide estate, was granted to the bishop of Winchester, and Alfred gave his daughter Ashton Keynes. Boundary clauses of probable late Anglo-Saxon date, and corresponding to later parish boundaries, are attached to charters of Purton and South Cerney (Glos.), which borders Ashton Keynes, Cricklade and Latton. Preconquest fabric survives in Minety and Purton parish churches, and St Sampson's, Cricklade. Eisey's name, apparently referring to an island of high ground sacred to a deity, suggests that its church may have christianised a formerly pagan site.

Clues such as these, to the gradual transformation of the Romano-British agrarian and settled landscape into that inventoried in Domesday book, should be set into the wider political context of Anglo-Saxon England. (fn. 6) From the beginning of Anglo-Saxon control of the region in the late 6th century until the 9th-century threats of Viking invasion, the upper Thames valley was debatable land between the kings of Wessex and Mercia. The ragged county boundary and the ambiguous allegiances of its bordering parishes attest to this, as do the grantors of its estates – Burgred and Ecgfrith, Mercian kings; Caedwalla, Æthelwulf and Alfred of Wessex; and Baldred, probably a client-king of Wessex. Against a common enemy in the late 9th century the burh of Cricklade was built as a fortified stronghold to control the strategic Thames frontier against potential Danish Viking attack. Refurbished in the early 11th century it fell to the Danish king Cnut, and its walls were disabled. The extent to which these centuries were a period of intermittent warfare affected the daily lives of the region's inhabitants should not be overestimated, but must be included, alongside topography and agriculture, in any consideration of its tenurial and settlement history.

THE HUNDREDAL STRUCTURE

The parishes included within this volume constituted by the 14th century the western portion of Highworth hundred. (fn. 7) This was an amalgamation of the Domesday hundreds of Highworth, Scipe, Cricklade and Staple. Before the amalgamation Highworth hundred court held jurisdiction over Highworth and its dependent tithings, as well as the parishes of Castle Eaton, Hannington, Inglesham, Marston Meysey and Stanton Fitzwarren. Scipe hundred comprised Blunsdon St Andrew, Rodbourne Cheney and Stratton St Margaret parishes. All these parishes, except Marston Meysey (which is included here), are reserved for treatment in a future volume on the eastern half of Highworth hundred.

Staple hundred met at Purton, where the names Staple Cross way, Staple Piece, and 'le Westapele' apparently record its meeting places. It had jurisdiction over Purton (apart from Braydon), Lydiard Millicent, (fn. 8) Lydiard Tregoze, and the manor of Water Eaton in Eisey parish. Cricklade hundred held jurisdiction over Ashton Keynes and its tithing Leigh, Braydon (a tithing of Purton), Cricklade, Eisey (apart from Water Eaton), Latton, and Somerford Keynes. All the parishes of Staple and Cricklade hundreds are included in this volume apart from Somerford Keynes, which was transferred to Gloucestershire in 1897, and which will be covered in a future volume of the Gloucestershire series; and Lydiard Tregoze, which later came under the jurisdiction of Kingsbridge hundred, and is covered in Volume IX of the Wiltshire series. In addition the present volume considers Minety, a detached portion of the Gloucestershire hundred of Crowthorne and Minety, which was transferred to Malmesbury hundred, Wiltshire, in 1844.

Wiltshire's erratic hundredal division, well seen in this north-east corner of the shire, may be the result of several centuries of modification, influenced by landownership and minster parochiae. (fn. 9) In the geld rolls of 1084 the attribution of Domesday estates to hundreds differs from that in use later. Staple hundred included Purton, Chelworth, Calcutt and (probably) Lydiard Millicent, 52 hides in total. Cricklade hundred comprised Ashton Keynes, Latton and Eisey, and three estates now in Gloucestershire – Shorncote, Poulton and Somerford Keynes – a total of 49 hides. (fn. 10) Taken together these two Domesday hundreds may be halves of an earlier 'true' hundred of 100 hides, and it has been suggested that the division took place after the burh of Cricklade was established, to enable both Purton church and St Sampson's, Cricklade, to be regarded as minster churches responsible for their own hundreds. (fn. 11) The 1084 hundred totals for Highworth (60 hides) and Scipe (80 hides) both fall short of 'true' hundreds, and their origins remain obscure.

In the Middle Ages the lord of Cricklade manor was also the lord of Cricklade hundred and enjoyed liberties over it, defined in the 1280s as execution and return of writs, pleas of vee de naam, gallows, pillory, tumbrel, and the assize of bread and of ale. (fn. 12) The burgesses owed suit to the hundred, (fn. 13) the suit to it of other men was apparently withdrawn by their lords, and probably from the 13th century the three-weekly hundred court and the twice-yearly view dealt only with the business of Cricklade borough. The court and the view apparently met regularly in the 15th and 16th centuries. (fn. 14) In the 18th and 19th centuries the view was called the court leet and view of frankpledge of the lord of the manor of the borough and hundred of Cricklade. (fn. 15)

By the early 1220s, the abbot of Tewkesbury had withdrawn his men of Ashton Keynes from Cricklade hundred court, when the lord of the hundred made an unsuccessful attempt to compel him to return them. (fn. 16) Cirencester abbey may have withdrawn its men of Latton and Eisey from the jurisdiction of Cricklade hundred by 1258, when the lord of the hundred sold all his claims against the men, except in respect of return of writs, to the abbey for 40 marks. (fn. 17) In 1259 the abbey's men of Latton were formally exempted from suit at the courts of the hundred. (fn. 18) In 1289 the abbey claimed the right to have a tumbrel and gallows and to enforce the assize of bread and of ale for Latton. (fn. 19) This probably applied to the men of Eisey.

Adam of Purton shared lands inherited from his uncle Thomas of Sandford with his cousin Hugh Peverell. They held the lordship of Chelworth, which was associated with the lordship of Staple hundred and the serjeanty of Braydon forest, and included lands in Purton. (fn. 20) In 1334 Purton residents paid 140s. out of a total of 216s. in tax collected in Staple hundred. (fn. 21) The men of Water Eaton in Eisey parish were under the jurisdiction of the courts of Staple hundred until 1232, when Godstow abbey withdrew them from it. (fn. 22) In 1275 the abbey was holding view of frankpledge for Water Eaton and enforcing the assize of bread and of ale there. (fn. 23) The right to hold a view and to exercise leet jurisdiction in Water Eaton passed with Water Eaton manor in the 16th century. (fn. 24)

The men of Lydiard Millicent and Shaw were not exempt from the jurisdiction of Highworth hundred, so no leet jurisdiction was exercised by the manor court. (fn. 25) In the Middle Ages the inhabitants of Marston Meysey were subject to the jurisdiction of the lord of the manor and borough of Fairford (Glos.), who held courts in the village in the 1480s. (fn. 26) The bishops of Salisbury held manorial courts until 1869. (fn. 27)

BRAYDON FOREST

Away from the Thames-side parishes of Latton, Eisey and Marston Meysey, all the communities described in this volume possessed land which was at times claimed by the Crown to lie within the bounds of the royal forest of Braydon. Many aspects of the forest's history, including its boundaries, administration and disafforesting, have been described elsewhere; (fn. 28) its impact on the settlement pattern and economic life of the area has been profound. The forest or wood of Braydon, in existence by the late 7th century, (fn. 29) was certainly subject to Anglo-Norman forest law, administered by its own courts and officials, by the 12th. Tenants of manors which fell within the forest bounds were thus subject to two jurisdictions, that of their manorial courts for most day to day affairs and that of the forest courts for all issues relating to the specific requirements of the forest laws. Designed to protect the forest game and its habitat, these laws were always irksome to local inhabitants and the fines which they imposed for offences or for release from their restrictions came to be regarded as a form of special taxation. Already by the late 13th century, the area subject to the full weight of forest law was being reduced, but the system and its courts continued in existence in Braydon and its environs until the 17th century.

The exploitation of Braydon forest falls into four phases. In the Anglo-Saxon period, when it was variously known as Ordwoldeswode and Bradon (or variants), (fn. 30) it formed part of Selwood, the vast tract of woodland and wood-pasture which occupied much of the claylands from north Dorset through west and north Wiltshire and into Oxfordshire. Sparsely settled, its main value was as a source of wood and pannage for those communities that developed at locations more favourable for agriculture around its perimeter, and whose territories, more or less defined, extended into it. A pattern of boundaries, like those of the fingers of touching hands, intrude into the forest from east and west. Systematic woodland clearance by assarting had taken place in the Anglo-Saxon period at Chelworth, and perhaps somewhat later (by the men of Ashton Keynes) at Leigh also. Elsewhere, the wooded forest may have been used for hunting by Anglo-Saxon kings, and animals of the surrounding farmers intercommoned in the less densely wooded pastures.

Before 1135 Braydon was declared a royal forest, and bounds were perambulated in 1228 which embraced all land south of the Thames and west of the Ray, thus effectively the whole of Cricklade, Purton, Lydiard Millicent and Minety parishes, and their neighbours to south and west. This area was reduced in 1279 by withdrawing the boundary westward to the river Key, below the Corallian ridge, thus placing all the main settled areas (apart from Minety and Leigh) outside the forest bounds. Within the forest wild animals and trees were protected, and assarting was forbidden, although the traditional pastoral farming continued, and some privileges were granted to religious foundations, such as Cirencester abbey in their woods at Minety, and St John's hospital, Cricklade.

Further retrenchment took place in 1300 (confirmed in 1330), restricting the forest to fingers of clayland west of the river Key in Purton and St Sampson's, Cricklade parishes. This block, the wooded heart of the forest, was largely Crown land, although the three 'rags' – Duchy, Pouchers, and Keynes – belonged to manorial lords. All the former forest land to north, south and west became the Braydon purlieus, where landowners were released from the harsher restrictions of forest law, but could not enclose it, so intercommoning by neighbouring manors continued.

The survival until the 17th century of the royal forest surrounded by its unenclosed purlieus served as a brake on agricultural change and improvement, and also restricted the creation of new settlements and farmsteads in the area. Only after the Crown lands were enclosed following the final disafforesting of Braydon in 1630, and the owners of the purlieus followed suit, was the medieval pattern of land use modified and expunged.

SETTLEMENT

The land described in this volume contains a variety of medieval and earlier settlement forms. A feature of the Thames-side communities appears to be a phase of small-scale nucleation around church and manor house, followed by a planned row village nearby. This is best seen at Latton, where a cluster of buildings around the church stands some 300 m. away from Ermin Street, along which a village of regular crofts was later set out. Something rather similar seems to have happened at Marston Meysey, and perhaps at Eisey, although here subsequent depopulation and canal-building have obscured any pattern. Calcutt, like Latton, was built as a regular row along Ermin street. At Ashton Keynes a more complex plan appears to be the result of two early foci, one around the church, the other centred on a defensive site; to these village planning in the 12th century and later (presumably by its monastic owner, Tewkesbury abbey) added a cruciform and ultimately gridded street plan, perhaps with the intention of promoting the settlement into a small town. Elsewhere, in the valley and on the claylands, a more dispersed pattern with some nucleation is apparent, as at Water Eaton (later partly deserted); Widhill, where two distinct small settlements developed with a chapel between them; and Purton Stoke, where some of the houses were ranged around a possible green. The dispersed pattern of farmsteads and associated closes at Chelworth and Leigh can be shown to be the results of early assarting. Moated sites were built on the clayland east of the river Key (and so outside the purlieus) at Bentham, Widham and Purton Stoke (all in Purton) and at Lower Chelworth (Cricklade); it has been suggested that they are of 13th-century date. (fn. 31)

On the Corallian ridge also row villages were established. That along Lydiard Millicent street may have been planned, and supplemented a nucleation around the church, which is now obscured by garden landscaping. At Shaw in Lydiard Millicent a looser row of farmsteads and closes along a lane survives in part amid recent suburban development. Purton had a dispersed pattern of farmsteads and small hamlets on the ridge, including North and South Pavenhill, Dogridge, Restrop and Bagbury, but (as at Latton) there seems also to have been settlement shift from the early nucleation around the church and demesne house (Church End) to a planned row of houses ranged along the high street, which was an important medieval thoroughfare. The effect of this road, which ran westward into the forest, was to attract linear settlement along it in the middle ages as far as Pavenhill.

Two settlements not so far considered, Cricklade and Minety, have unusual features. Cricklade is one of a network of fortified urban sites, known as burghal hidage forts, created c. 880 by Alfred. Like Wareham (Dorset) and Wallingford (Berks., later Oxon.) it has a very regular square plan and, also like them, developed into a small but important medieval town within the confines of its Saxon rampart. Minety, alone of the communities discussed in this volume, was established at an early date not on the edge of Braydon forest, but close to its wooded centre. It has been suggested, perhaps implausibly, that this reflected the continuing significance of the Roman pottery industry there into the Saxon period. (fn. 32) Whatever the explanation Malmesbury abbey, which owned it from 844, appears to have built a village, now largely deserted and represented by earthworks, around its church; the manor was lost by Malmesbury and acquired by Cirencester abbey in the 12th century. Because the parish was then transferred to Gloucestershire, but the church and c. 40 a. around it remained in Wiltshire, it is possible from a map of its bounds in 1777 to gauge the probable extent of the preconquest village with its appurtenances. This early focus appears to have atrophied after its lands passed to Cirencester, and a more dispersed settlement pattern emerged across the parish.

LANDOWNERSHIP

Within a century of the Norman conquest rather more than 70 per cent of the area under scrutiny belonged to monastic houses. Their landholdings had accumulated in various ways. The large estate of Purton had belonged to Malmesbury abbey since the 7th century, and was an important component of its portfolio, which also included the Wiltshire portion of Minety. Ashton Keynes (with Leigh) was also a pre-conquest monastic possession, which was transferred in 1102 from Cranborne abbey (Dorset) to help found Tewkesbury abbey (Glos.), when Cranborne became its cell. The founding endowment of Cirencester abbey in 1133 included most of Minety, previously part of the Crown's Cirencester manor, as well as Eisey and Latton, which had been granted to the king's chancellor, Rainbold, after the Norman conquest and later reverted to the Crown. A layman gave Water Eaton (in Eisey) to Godstow abbey (Oxon.), c. 1142, and small estates in Chelworth (Cricklade) were later given to Godstow and to Merton priory (Surrey). Apart from Malmesbury's Minety estate, which it surrendered to the bishop of Salisbury in 1270, all these lands remained in their monastic owners' hands, although with varying degrees of direct control, until the dissolution, c. 1539.

Two pre-conquest estates held by laymen, Lydiard Millicent and Marston Meysey, were given by William to Norman lords, and were held throughout the middle ages intermittently by landed families and the Crown. Braydon, a tithing within Malmesbury abbey's Purton estate, was nevertheless regarded as Crown property, and was administered as part of Aldbourne manor, and later the duchy of Lancaster. Cricklade was a royal borough, whose burgesses never achieved selfgovernment; its seigneurial income was regarded as a manor which, combined with the lordship of Cricklade hundred, was claimed at various times by the Crown, members of the royal family, and Crown officers by serjeanty. Rural Cricklade, many of whose landholdings originated as pre-conquest assarts, has a complicated medieval manorial history. The principal Chelworth manor was held by the king's servants from the 11th to the 13th century, latterly (and perhaps throughout) by serjeanty of keeping Braydon forest. Thereafter, male lines failing, the manor fragmented and divisions became confused with the various freehold assarts, in both Chelworth and Calcutt. Two small Domesday manors at Widhill, also in rural Cricklade, descended in lay hands with those of nearby manors.

Confused and diverse landownership around Cricklade from the 13th century onwards is mirrored, not only by those manors under seigneurial control, but also at Purton. Here the manorial overlord, Malmesbury abbey, was content to devolve direct control to free tenants, and these became regarded as lords of manors. A fee accumulated by Adam of Purton, including lands in Chelworth, Purton and Ashton Keynes, and Staple hundred, was divided when he died c. 1266 without male heirs, and thereafter three Purton manors co-existed with other free holdings there, at Restrop and Pavenhill, until the 16th century.

At the Dissolution all monastic land was claimed by the Crown, and most was leased or sold to laymen, although some Braydon forest land was retained in hand. The principal beneficiaries of this wholesale redistribution of the area's land were two magnate families, Bridges and Hungerford. Sir John Bridges, later Lord Chandos, already held under Malmesbury abbey the manors of Purton Keynes and Purton Stoke, and to these he added Minety and Water Eaton (in Eisey). The remainder of Eisey, together with Latton, was sold to Sir Anthony Hungerford, who also took Ashton Keynes on a long lease. Hungerford subsequently acquired Leigh, land in Chelworth, and two estates in Purton. By the close of the Tudor period, therefore, most land in the area belonged to a few prominent families, with the remainder under the direct control of the Crown (Cricklade borough, Braydon forest) or the church (Minety rectory, and Marston Meysey, which was acquired from the queen by the bishop of Salisbury in 1564).

ECONOMIC SURVIVAL

Notwithstanding the emphasis on pastoral farming in later centuries, openfield arable cultivation was practised by most, if not all, the medieval communities in the area on a large scale. Where acreages can be estimated, at Ashton Keynes, Chelworth, Eisey and Latton, the extent of arable land was approximately twice that of meadowland. Over 40 per cent of Latton's land was arable in the Middle Ages, and at Marston Meysey in the 17th century arable may have exceeded 60 per cent of the parish area. The highest proportions were on the Thames-side manors, where gravel deposits overlying the clay proved favourable to crops. The brashy soils of the Corallian beds were also suitable for cultivation, and open fields were laid out along the ridge at Lydiard Millicent, Restrop in Purton, and Purton itself. Later evidence suggests that three-field systems operated at Ashton Keynes (where north, east and west fields survived to the 18th century), Marston Meysey and Eisey; but at Water Eaton in the 12th century there were two open fields, south and east; Leigh may have had a single open field. Chelworth in the 15th century had four fields, one of which was a hitching field cropped every year. Evidence for strip cultivation comes not only from documentary evidence, such as a detailed Purton parish map of 1744, but also from surviving ridge and furrow, as at Leigh chancel, and identified from aerial photography. (fn. 33)

Stock husbandry, principally oxen and dairy cattle, and sheep, was also widespread in the middle ages, and was especially important on the predominantly clayland manors, such as Minety and Purton Stoke. All communities, except the Cricklade burgesses, had common pastures and meadows, and most also had fingers of rough wasteland or wood-pasture extending into Braydon, sometimes undefined, in which intercommoning of the stock of neighbouring manors took place. Beasts could also graze the open arable in common when fallow, and at prescribed times the extensive meadowlands which lined the banks of the Thames and its headwaters. Lammas meadows, into which animals were turned to feed as common pasture grounds for half the year, between 1 August (Lammas) and 2 February (Candlemas), are recorded at Marston Meysey and Minety; North Meadow, Cricklade is a spectacular survivor of national importance, conserved for its botanical richness, which originated and was strictly managed as separately delineated freeholds attached to each Cricklade burgage plot.

Economic activity aside from the threshing-floor and dairy was concentrated on the area's only town, Cricklade, although the usual range of trades was found in the countryside. The Thames and its tributaries the rivers Churn and Ray were sufficiently powerful to turn watermills at Ashton Keynes, Cricklade, Chelworth, Latton, Widhill and Purton, but not every community had its own mill – Eisey relied on Latton – and medieval windmills harnessed alternative power at Chelworth, Lydiard Millicent and Purton (and later at Ashton Keynes and Minety). The Minety clay enabled a colony of medieval potters to supply local markets with everyday ceramics, and 'Minety ware' is widely found on archaeological sites in north Wiltshire and south Gloucestershire. Pottery was also made at Ashton Keynes, alongside cloth- and leather-working. Purton, which extended to Dogridge and Pavenhill along an important medieval thoroughfare between Oxford and Bristol, doubtless derived economic advantage from its position by providing services to travellers.

Cricklade in the late Anglo-Saxon and medieval periods was a significant town, with a weekly market and two or more annual fairs. It had a mint in the lateSaxon period, merchant traders, including Jews, in the 13th and 14th centuries, and was summoned to send representatives to Parliament as a market town in 1275. Markets were presumably held in the wide high street, which was probably lined with business premises as well as houses, and butchers' shambles were recorded in 1442–3. Lying astride the diverted Ermin Street, an important medieval route between south-east England, the midlands and south Wales, Cricklade would have benefitted from passing trade. The usual range of foodstuffs was sold in the town, and there were also manufacturers of cloth, gloves and shoes, as well as coopers and smiths. Merchants doubtless also traded in agricultural commodities from the town's hinterland.

RELIGION AND SOCIETY

The area's monastic landowners unsurprisingly supervised also much of its religious life. Malmesbury abbey was probably responsible for building preconquest churches on its estates at Minety and Purton, and possibly also at Chelworth, an estate it subsequently exchanged away. It has been suggested that Purton was intended as a minster church, and St Sampson's, Cricklade, successor to Chelworth, may also have had minster status. (fn. 34) Cranborne abbey or Tewkesbury abbey, which succeeded it as owner of Ashton Keynes, was presumably responsible for building a precursor of the present 12th-century church there. All these churches were well endowed, and survive as impressive medieval buildings. Eisey church, whose name suggests that it was established on a pagan site, and its neighbour Latton, were probably served by priests from Cirencester minster, before being appropriated by Cirencester abbey as part of its foundation endowment in 1133. The present Latton church was probably rebuilt by Cirencester around this time. Cranborne or Tewkesbury appropriated Ashton Keynes rectory, and Malmesbury appropriated Purton and Minety, although the latter was ceded in 1270 to the bishop of Salisbury for the benefit of the archdeacon of Wiltshire. Lydiard Millicent church was probably intended by its founder to endow Cormeilles abbey in Normandy, which he also founded soon after the conquest, but attempts by Cormeilles and its daughter house at Newent (Glos.) to appropriate Lydiard's rectory were thwarted. After St Sampson's, Cricklade, was appropriated by Salisbury cathedral c. 1430 the only parishes served by rectors rather than vicars appointed by religious bodies were Lydiard Millicent and St Mary's, Cricklade.

Not all medieval places of worship in the area under scrutiny were or became parish churches. Leigh, of which the medieval chancel survives, was a dependent chapel of Ashton Keynes served by chaplains. Likewise Water Eaton chapel, demolished in 1673, was dependent on Eisey and served by its patron, Cirencester abbey. St Sampson's, Cricklade, was described as the mother church of St Mary's before that achieved parochial status, and St Sampson's also had a dependent chapel dedicated to St Michael in the town, possibly in Calcutt street, and a chapel at Widhill. Both are lost. Marston Meysey was served until the 19th century by a chapel dependent on Meysey Hampton (Glos.). Two influential landowners, father and son, were permitted to build private places of worship. Thomas de Purton was allowed by Malmesbury abbey to build an oratory in his court at Purton; and his son Adam (d. c. 1266) built a chantry chapel on his manor at Ashton Keynes. A 14th-century chantry chapel, which may have been used as a lady chapel, survives in Purton church, around which exquisite medieval wall paintings were uncovered in the 19th century. St John's hospital was a religious institution for elderly priests established in Cricklade c. 1220.

INTO THE MODERN WORLD

THE BRAYDON TRANSFORMATION

In the Tudor period the move to inclose open arable farmland and convert it to pasture held in severalty was felt everywhere on the north Wiltshire claylands and the upper Thames valley. (fn. 35) On the small manor of Water Eaton all common agriculture had been extinguished by the early 16th century, and some common arable, meadow and pasture at Ashton Keynes was inclosed c. 1590. The lord of Lydiard Millicent, whose territory extended far into Braydon but was not purlieu land, had inclosed all common arable and pasture by 1571, thus setting an example for his neighbours.

The Crown's attempts from 1573 to enforce forest law in Braydon and to discipline owners of the purlieus who pastured animals in the forest met with little success. (fn. 36) In 1613 it was claimed that the lessee of the woodlands was destroying them by overexploitation, and that £30,000 could be raised by disafforesting and enclosing the forest as farmland. Arrangements to do this were made between 1627 and 1630, and the disafforested Crown land was leased to contractors who enclosed woodland and waste, converted lodges to farmhouses and created new farms. Landowners of the purlieus, denied access to former forest land but no longer constrained to keep the forest fringes-edge open, also began the process of inclosing and converting land to pasture, granting where they could not avoid it allotments to tenants in lieu of common rights.

This movement had three main consequences. It created the pattern of largely rectilinear field boundaries, divided and linked by straight driftways and lanes, which remain an almost universal feature of the clayland portions of the parishes covered in this volume. It accelerated the conversion of arable, woodland and waste to pasture for dairy farmers and graziers. And it resulted in a new dispersal of settlement, as isolated farms were built surrounded by their fields, and squatter-type hamlets sprang up alongside roads and remaining patches of common waste. Some of the farmsteads were enlarged and aggrandised to become country houses, while the squatter hamlets were renewed and augmented by modern houses.

These processes are well seen at Lydiard Millicent and rural Cricklade. Eight outlying farmsteads existed in Lydiard Millicent's slender parish by 1839, and six hamlets had grown up along roads or at junctions, including Green Hill, Lydiard Green and Greatfield, which all now consist predominantly of 19th- and 20thcentury housing. In the former forest area of Cricklade two keepers' lodges became farms, eight new farmsteads were built before 1800 and a further eight during the 19th century. The pattern was repeated at Purton and Minety, and away from the forest at Ashton Keynes, where respectable squatter hamlets appeared at North End, Kent End, Rixon Gate and Happy Land.

The Minety graziers were noted for fattening livestock for the London market, but dairy farmers predominated in the area, producing cheese and, from the mid-19th century, liquid milk for conveyance by rail to London and Birmingham, or for the burgeoning population of Swindon on its doorstep. Minety railway station was built in 1841 with cattle and milk loading facilities, and not only revolutionised the local dairy industry, but also stimulated the 19th-century development of Lower Minety as the principal settlement within the parish. Blunsdon station, on the Purton border, was also primarily concerned with milk traffic, and Cricklade station had loading bays for milk and cattle. At Latton a creamery to produce and package milk products was opened beside Ermin Street in 1935.

TRANSPORT AND ECONOMY

Although the medieval Oxford to Bristol thoroughfare through Purton was the only main road to be mapped crossing the area in 1675, it is likely that Calcutt, Cricklade and Latton continued to benefit from passing trade along Ermin Street. (fn. 37) During the 18th-century turnpike era, Purton lost out to Cricklade, as the former's road declined in importance, whilst Cricklade became the hub of four turnpike roads, west to Malmesbury and east to Blunsdon and Highworth in 1756, north to Cirencester in 1758, and south via Purton to Wootton Bassett and Calne in 1791. One late turnpike trust, sanctioned in 1810, impinged on the area, controlling the roads from Cirencester to Wootton Bassett through Ashton Keynes, and a road from Lower Minety to Crudwell.

By then other means of travel were available. The Thames & Severn canal was built across Latton, Eisey and Marston Meysey parishes in 1789, with a wharf between Latton and Cricklade, whose laborious river passage it probably replaced. A second canal, the North Wilts., was built in 1819 from Swindon to Latton, skirting west of Cricklade, to connect the Wilts. & Berks. canal with the Thames and Severn. The activities of both were curtailed by the Great Western Railway, whose 1841 line branching at Swindon towards Stroud, Gloucester and Cheltenham, with stations (now closed) at Purton and Minety, crosses the claylands. A second railway line, part of a projected route from north-west England to the south coast, opened between Rushey Platt, west of Swindon, and Cirencester in 1883, with stations at Blunsdon and Cricklade, but closed in 1963. The 20th-century growth in motor traffic led to the designation of Ermin Street as a trunk road in 1946, with by-passes around Cricklade and Latton, and other improvements made between 1975 and 1997. No other primary route crosses the area, which is served by Band C-class roads, although an entirely new access road, for quarry and water park traffic, was built across Ashton Keynes parish in 1971.

Until the later 19th century few of the area's inhabitants derived a living from an occupation not connected with agriculture or the handling of agricultural products. The usual suite of retailers appropriate to a small town was to be found at Cricklade, and assorted shops traded at Purton and some villages. A little gloving and leatherworking were carried on at Ashton Keynes and Cricklade, a distillery at Minety failed in 1859 within two years of opening, but a spa at Purton Stoke, which opened in the same year, sold bottled water until 1948. Although the Minety pottery industry had probably finished by the 16th century, potting continued at Ashton Keynes until c. 1860, and local clay was also used for brickmaking there, and at Lydiard Millicent, Water Eaton and Purton. Quarrying the local ragstone for building was carried on at Purton, but the most important, extensive, ongoing and highly visible extractive industry since c. 1970 has been the winning of gravel from sites along the Thames valley and its tributaries, most noticeably around Ashton Keynes, Latton, Eisey and Marston Meysey.

In the 20th century ease of travel meant that commuting to work, here as everywhere else, became commonplace, although Swindon railway works employees were living in Purton and Lydiard Millicent some decades before 1900. Travel itself became a source of employment, for a haulage contractor, motor coach proprietor, and small-scale engineering works. On an altogether larger scale RAF Blakehill Farm, opened in 1944 for military flying and aircraft maintenance, occupied part of the former Braydon forest in Cricklade parish. It closed as an airbase in 1946, but remained a government establishment, and became a wildlife site in 2000; another airfield, RAF Fairford, has since c. 1950 bisected Marston Meysey parish and remains operational.

BUILDINGS AND SOCIETY

A cruck-framed cottage in Ashton Keynes and a twobay hall concealed within later stone walls in Cricklade high street are rare survivors of medieval timberframed architecture. Parts of a stone vicarage house of c. 1300 are incorporated in a Cricklade house now known as Candletree. Typically, however, throughout the area covered by this volume medieval domestic buildings were replaced from the late Tudor period onwards by stone-built houses and cottages made of local ragstone from the Corallian beds or rubble limestone from the Cotswold edge, with occasional dressings of ashlar or brick, and roofed with stone slate or thatch. The use of local orange-red brick for cottages, Victorian villas, farmhouses and their outbuildings became widespread in the 19th century, sometimes including vitrified brickwork as decoration, and clay roof tiles were widely used. The vernacular tradition was lost in the massive 20th-century expansion of housing which most communities experienced, especially at Purton, Ashton Keynes, Cricklade and Minety, but a return to 'Cotswold-style' houses was attempted in a recent development at Latton.

Although there are no mansions or great houses within the area, former Braydon lodges and some farmhouses have been rebuilt and enlarged in the architectural styles of their day. Examples include Restrop House, Purton, of c. 1600; Red Lodge, Braydon, of 1643 and later; several houses in Cricklade high street of c. 1700; Braydon Hall, Minety, of 1751 (altered in 1920); Bentham House, Purton Stoke, of c. 1850; and Marston Hill House, Marston Meysey, of 1887. At Latton, a closed village of the earls of St Germans, a campaign of renewing farmhouses in similar style was embarked on from the early-19th century, and these were joined later by picturesque cottages with Tudor detailing.

Purton has retained many good examples of highstatus houses from the late-Tudor period to the mid18th century, reflecting the prosperity of its leading families in the early modern period. At Cricklade, by contrast, the burgesses were relatively impoverished in the 15th and 16th century, and disrupted by the civil wars. Substantial new building and rebuilding only resumed after a fire in 1723, by when increasing through traffic and the profits from corrupt elections were enriching some of the town's inhabitants. Good quality houses in the village centres of Lydiard Millicent and Marston Meysey also suggest periods of affluence.

Religious buildings have experienced mixed fortunes. Notable medieval churches survive at Ashton Keynes, Purton and Minety; the 16th-century tower of St Sampson's, Cricklade, dominates the little town and is a landmark for many miles. Most medieval churches underwent extensive alterations by Victorian restorers. Butterfield was the architect at Latton (1858–63), Purton (1871–2) and Ashton Keynes (1876–7), Ewan Christian at St Sampson's (1863–4), and G. E. Street at Lydiard Millicent (1870–1). St Mary's, Cricklade, was restored in C. E. Ponting's late Arts-and-Crafts style in 1908, and has since 1984 been used for Roman Catholic worship. Three entirely new churches were built: at Eisey in 1844, on the site of its predecessor, and demolished in 1953; Marston Meysey's church dates from 1876, replacing a tumbledown chapel-of-ease; and at Leigh between 1896 and 1898 fabric from the old chapel was used (by Ponting) to build on a new site, leaving the former chancel in situ as a mortuary chapel. Anglican confidence is seen also in the replacement of inadequate parsonages by large and stylish houses, as at Latton in 1827, Lydiard Millicent in 1855, and Purton in 1912.

Few public or community buildings call for comment. Protestant Nonconformity was patchily influential. There were early Quakers at Ashton Keynes and Purton Stoke, and Dissenters of various stripes worshipped in Purton and Cricklade, where an Independent meeting-house of 1799 survives. A vigorous campaign by Primitive Methodists evangelising from Brinkworth touched most communities in the area, and has left a sprinkling of small chapels. At Ashton Keynes a Christian commune known as the Cotswold Bruderhof established a farm in 1936, which was converted by a charity in 1941 into an approved school, the Cotswold Community. Jenner's school was built in Cricklade under the terms of an endowment in 1652 and its building survives. It remained a school until 1719 and then became St Sampson's parish workhouse. In 1835 this closed, when Cricklade and Wootton Bassett combined with other parishes, including all those described in this volume except Minety, to form a poor-law union; the main block is preserved of its union workhouse, built near Pavenhill in Purton, and later renamed North View Hospital. Elementary education was provided in the 19th century, generally with support from the National or British societies, in village schools. The British school at Ashton Keynes, dating from 1823, is unusually early. Although the smaller schools have closed, others grew inordinately large. Cricklade primary school had 499 pupils in 1979 before it was separated into infant and junior schools. Secondary education has been provided since 1963 for the area (except Minety, whose pupils attend Malmesbury) by Bradon Forest comprehensive school at Purton.

WEST OF SWINDON

In 1980 approximately one-third of Lydiard Millicent ancient parish, including the village of Shaw, was transferred to Swindon to accommodate part of the town's planned western expansion. By 2001 the ward which is almost coterminous with this transferred area had a population in excess of 9,600, at a density of over 28 persons per hectare. By contrast Marston Meysey in the same year recorded one person to 3 ha. and Braydon had probably one person to 12 ha. (fn. 38) As Swindon has grown since 1840 the parishes considered in this volume have striven to stay apart from their precocious neighbour, and to a large extent they have succeeded. Administratively they remain distinct, and their communities have preserved their individuality and a rural demeanour. There are wetlands, lakes and wildlife reserves, remote woodland vistas sprinkled with isolated cottages, ancient churches and picturesque stone villages, and the pervading whiff of the dairy herd. But in truth such places co-exist in symbiosis with Swindon, upon whom their inhabitants rely for goods and services, employment and entertainment, and the infrastructure of travel. In return their scenery, space and recreational amenities are readily accessible to Swindon's urban population, for them to enjoy and, it is to be hoped, conserve.