A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Originally published by Boydell & Brewer for Victoria County History, Woodbridge, 2011.

This free content was digitised by double rekeying. All rights reserved.

'Cricklade - Cricklade Borough', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18, ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/20-70 [accessed 30 April 2025].

'Cricklade - Cricklade Borough', in A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Edited by Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online, accessed April 30, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/20-70.

"Cricklade - Cricklade Borough". A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 18. Ed. Virginia Bainbridge (Woodbridge, 2011), British History Online. Web. 30 April 2025. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/wilts/vol18/20-70.

In this section

CRICKLADE BOROUGH

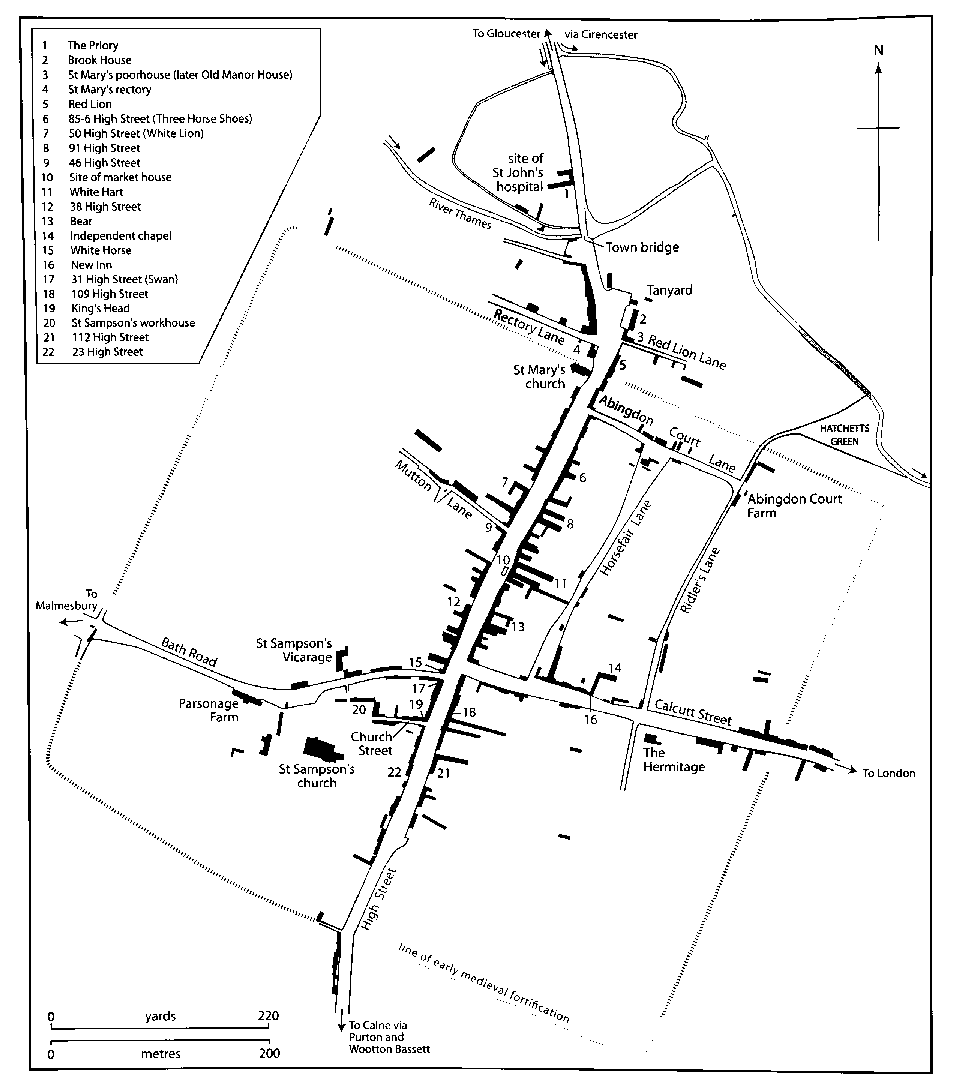

MAP 5. Cricklade: the town in 1830, showing the location of significant buildings mentioned in the text, and the line of the early medieval fortifications.

THIS article describes the Anglo-Saxon origins of the town of Cricklade, its subsequent development as a trading centre and Parliamentary borough, and its later history, including topography and built environment, civil and religious institutions, and government.

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

THE ANGLO-SAXON BURH

Standing as it did at the border between Wessex and Mercia, and at a strategic river-crossing, the establishment of Cricklade as a fortified town may have been a key element in Alfred's plan to defend his kingdom from any further Danish invasion from Mercia, immediately following his victory at Edington in 878. (fn. 1) Cricklade may be counted among the new settlements referred to c. 893 by Alfred's biographer. (fn. 2) It is one of the network of strongholds thrown across Wessex c. 880 and listed in the Burghal Hidage, a document of c. 919 or earlier. (fn. 3)

The town plan is rectilinear, and similar to those at Wallingford (Berks. later Oxon.) and Wareham (Dorset). It is laid out inside its defences within an almost square intra-mural walkway, apparently based (like other planned Anglo-Saxon towns) on multiples of a standard 4-pole (66 ft.) measure. (fn. 4) The town is bisected by a straight north–south street, and long, narrow plots running east–west from it were held by burghal tenure. (fn. 5) Calcutt Street, running westward from an east gate, bisects the eastern half into two equal quadrants, which are further divided by a grid of streets. The western half is crossed eccentrically by Bath Road, presumably reflecting a pre-existing routeway serving the settlement at Chelworth, and perhaps influenced by the position of a precursor on the site of St Sampson's church. (fn. 6)

It is likely that Cricklade's defences were begun c. 878–80. (fn. 7) Dump material from three shallow external ditches was thrown up to create a clay bank, c. 10 m. wide and c. 3 m. high, revetted with turf and probably surmounted by a wooden palisade and simple wooden corner turrets. A stone-paved intra-mural walkway was constructed at the same time. The fortifications enclosed a rough square with sides c. 180 m. long and containing c. 28 ha. Access to the town was through east and west gates on the Malmesbury road, and the east gate, which linked the town to Ermin Street, was probably the more important. Gates were also built at the north and south ends of the street. (fn. 8)

Early in the 10th century the defences were heightened and strengthened, a stone wall replaced the turf revetment, and a wall walk was constructed. This construction phase may have anticipated, or been a response to, a Danish raiding party which crossed the Thames, c. 902, and pillaged in and around Braydon forest, although it is not said to have attacked Cricklade. (fn. 9) In the Burghal Hidage document, Cricklade's fortifications were said to need 1,500 hides, implying a length of 2,063 yd.: their measured length is close to that. (fn. 10) It is likely that the wall then incorporated stone gatehouses. (fn. 11) The suggestion that a north gatehouse stood a little west of the street on what became the site of the north chapel of St Mary's church (fn. 12) has been dismissed because it would have obstructed the walk along the rampart. (fn. 13)

Following a period of neglect, the defences were refurbished, but then disabled by the destruction of the stone revetment and the filling with stones of the inner ditches. This episode may be ascribed to the second war with the Danes in the early 11th century, (fn. 14) when Cnut and his army crossed the Thames at Cricklade. (fn. 15) The dismantling of defences, at Cricklade and elsewhere, may then be seen as the victorious Cnut safeguarding his position. A further period of neglect was followed by a second reconstruction of the defences, involving the reexcavation of existing ditches and the creation of others, and a new wooden palisade. Documentary evidence suggests that this took place during the anarchy of the early 12th century. William of Dover was said to have constructed a castellum at Cricklade in 1144, which saw service in 1145 and 1147. (fn. 16) Thereafter further neglect was followed by an undated refurbishment and then a long period when the clay bank was allowed to spread and become lower. (fn. 17) It was plainly visible in the 18th and 19th centuries (fn. 18) and was excavated at several times and in several places between 1948 and 1998. (fn. 19) In the later 20th century the west part of the south bank was built over.

It has been suggested that, in the early 10th century, the revenues of an estate later called Abingdon Court manor were assigned to the maintenance of the north gateway and the northern line of the fortifications. (fn. 20) Although it is likely that this was one of the early assarts at Chelworth, and that it existed before Cricklade was built, (fn. 21) the suggestion seems fanciful. It has also been suggested that St Mary's church was built, rebuilt, or rededicated by the abbey of Abingdon (Berks., later Oxon.) in the early 11th century and that the abbey's estate was assigned to the church as its parish, based on the assumption that a small estate (haga or praediolum) in Cricklade granted by King Æthelred to the abbey in 1008 was the estate which became Abingdon Court manor. (fn. 22) The assumption seems groundless: the haga is more likely to have been a tenement in the town than an estate of land, (fn. 23) there is no evidence that Abingdon abbey held land or a tenement at Cricklade after 1008, (fn. 24) and Abingdon Court manor probably took its name from members of the Abingdon family who acquired it in the 13th century. (fn. 25)

Cricklade was a flourishing town in the 10th and 11th centuries. From the reign of King Æthelstan (925–39) it was important enough for coinage to be minted there: nine or more moneyers minted coins in the reign of Ethelred (970–1016), 10 or more in that of Cnut (1016–35), and minting continued until the reign of William II (1087–1100). (fn. 26)

A church was built by c. 980 and St Sampson's church was built or rebuilt on its present site west of High Street and south-west of the Malmesbury road in the late 10th or 11th centuries. (fn. 27) A lane running east from High Street to Abingdon Court manor and two lanes running north from the Malmesbury road came to form a small grid-pattern, although when is unclear. It has been argued that this is the only surviving part of a larger grid set out on both sides of High Street when the town was founded, but there is little evidence to support this theory. (fn. 28) Rather, it seems that the north–south lane nearer to High Street developed as a back lane, and the other two lanes were the main approaches to Abingdon Court manor. In 1086 the lords in demesne of 33 burgages are known, and there were many other burgages; it is highly likely that all of these stood along High Street between the fortifications. (fn. 29)

Because Calcutt Street and Bath Road are not aligned with each other where they cross High Street it has been suggested that the south side of Calcutt Street lay open to a rectangular market place which was later filled in with a cluster of small building plots. (fn. 30) A 14th-century stone market cross, (fn. 31) called the High Cross in the 15th century, (fn. 32) stood there until it was removed to St Sampson's churchyard c. 1817–20. (fn. 33) Records show that the market was held in High Street by the 17th century, (fn. 34) although the buildings which stand in neat rows on its probable site have more in common with normal street development than with casual market infill.

MIDDLE AGES

From 1139 Wiltshire was the scene of conflict between forces of the Empress Maud and of King Stephen, (fn. 35) and a chronicler recorded that in 1144 William of Dover, a supporter of Maud, went to Cricklade, 'which is situated in a delightful spot abounding in resources of every kind, and with the greatest zeal built a castle which was inaccessible because of the barrier of water and marsh on every side'. (fn. 36) Some ambiguity has led to the suggestion that it actually stood at Castle Eaton, (fn. 37) but the castle of Cricklade is referred to explicitly in an entry for 1145. (fn. 38) Especially if inaccessum meant difficult to enter rather than difficult to reach, it is almost certain that William either built or strengthened the stone walls around the town to provide defences prominent enough to be called a castle. William was castellan until 1145, when Maud replaced him with Philip, the son of Robert, earl of Gloucester. Philip deserted Maud and by 1147 Cricklade had passed into Stephen's hands; in that year Henry of Anjou was repulsed in his attempt to take it from the king's supporters. (fn. 39)

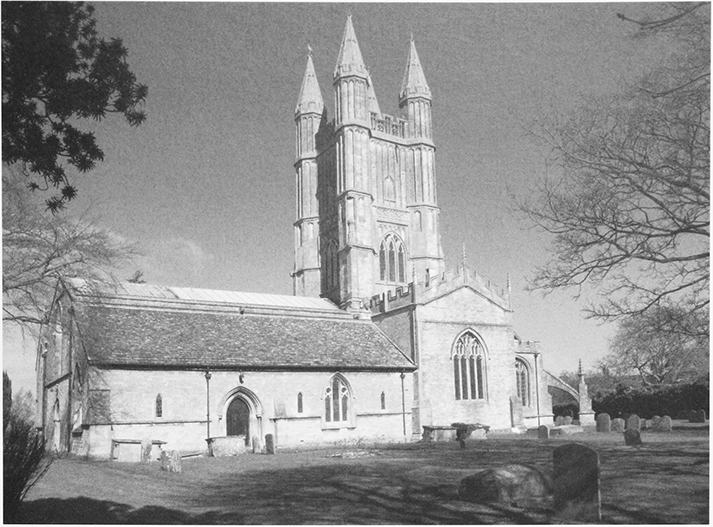

2. The parish church of St Sampson, from the south. The cruciform building, containing 12th-century and earlier fabric, is dominated by the early 16th-century crossing tower, which can be seen from miles around.

If William of Dover's castle was at Cricklade, the description of it as having water and marsh on every side would have been exaggerated, but it does imply that by the earlier 12th century the Thames had been diverted from the course followed by the parish boundary to that near the north end of the town. The diversion may have been to drive the mills which are known to have stood on it, (fn. 40) to give to the town easy access to craft carrying goods on the river, or to bring water to the town for general purposes. By 1225 a bridge, later called the town bridge, had been built over the river at Cricklade. (fn. 41)

In the Middle Ages Cricklade still exercised a military function from time to time and was sometimes visited by kings. (fn. 42) On one occasion in the later 13th century it was the meeting place of the justices of assize, (fn. 43) although it never become an administrative centre for the county. The presence of moneyers suggests that it was already a prosperous town in the late Anglo-Saxon period, and a 12th century grant to the burgesses of freedom from toll and passage suggests it was then home to a community of merchants. (fn. 44) There were wine sellers in the 13th century, (fn. 45) and there may also have been a goldsmith; (fn. 46) Jews were active in the later 13th and early 14th centuries, (fn. 47) when Cricklade's merchants bought goods in Flanders and exported wool through London; (fn. 48) in the 16th and 17th centuries there were still some merchants, (fn. 49) engrossing, dealing in cattle, and buying wool. (fn. 50)

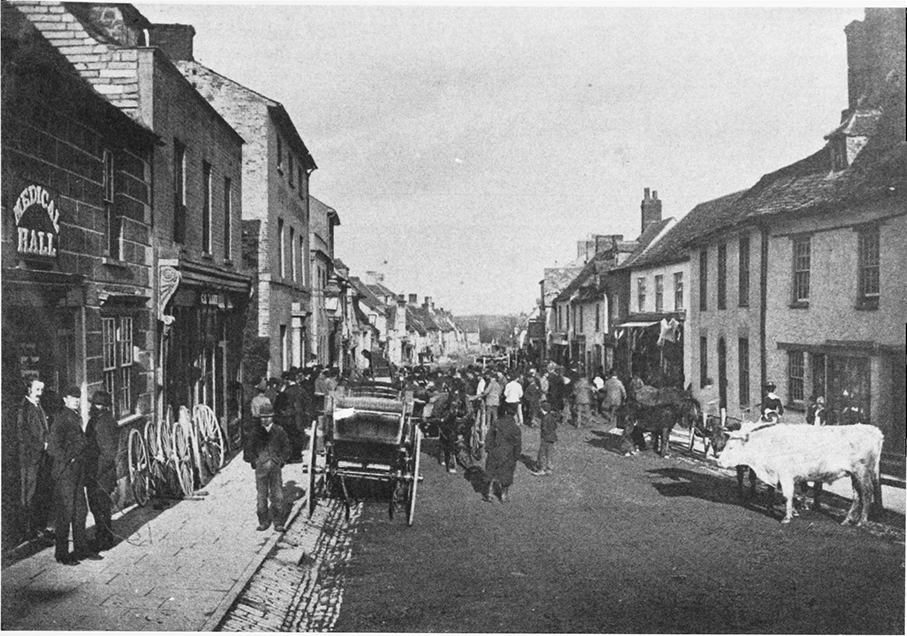

Cricklade's main street, called its great street c. 1270, (fn. 51) and High Street from 1412 or earlier, (fn. 52) almost certainly consisted of houses and business premises rather than of farmsteads. Shops and shambles stood there in the Middle Ages. (fn. 53) The streets called East Street and West Street in the earlier 15th century, (fn. 54) both presumably had buildings standing along them. East Street probably became Calcutt Lane in 1567 (fn. 55) and Calcutt Street later; West Street probably became Vicarage Lane c. 1546, (fn. 56) Church Lane in the 18th century, (fn. 57) and Bath Road later. Rutherns Lane, so called in 1332, (fn. 58) and Snows Lane, so called in 1416, (fn. 59) were probably narrow lanes leading between houses in High Street. Horsefair Lane, the back lane of High Street, was so called in the 16th century, (fn. 60) by when the early grid had probably been completed. No back lane developed behind the west side of High Street, probably because access into Bath Road would have been blocked by St Sampson's vicarage house and its garden.

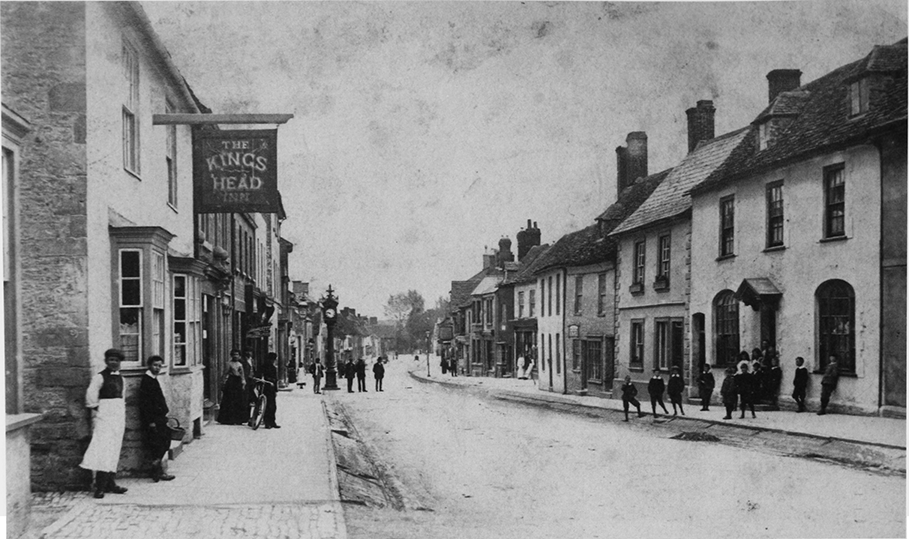

3. A view of High Street south of the junction with Calcutt Street, in the early 20th century. The King's Head, on the left, has since closed. On the right is Danvers House, used as a school c. 1900–34.

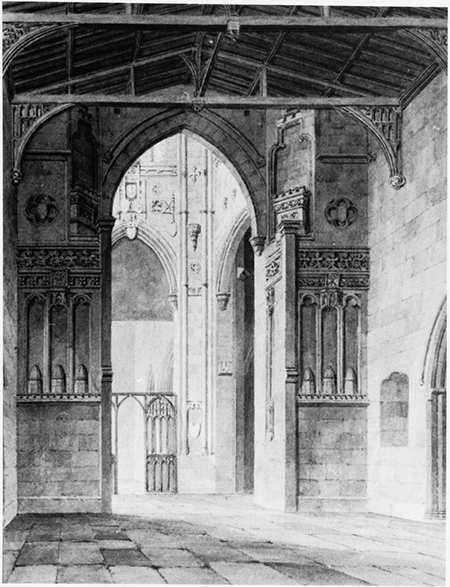

The earliest and most substantial medieval buildings known from surviving or recorded evidence are those that were associated with St Sampson's church. The vicarage house, later called Candletree, existed by the late 13th or early 14th century, and stood on Bath road with its farmstead. The use of stone in these buildings reflects their high status and the wealth of St Sampson's church. St Michael's chapel was built in the town possibly in the 11th or 12th century, and may have stood in Calcutt Street. (fn. 61) St Mary's church was built in the earlier 12th century at the north end of High Street; it was extended into the street in the 13th century, when its chancel was lengthened.

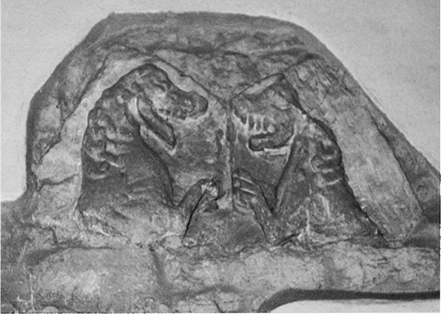

A 14th-century cross was moved from High Street to St Sampson's churchyard in the early 19th century. It has an octagonal base, ornamented with quatrefoils, and an octagonal shaft. The shaft carries an oblong head embellished with canopied niches; the pinnacles have been removed from the angle buttresses of the head, and sculptured figures have been removed from the niches. (fn. 62) An iron cross which formed a finial was blown down in 1915, repaired, and put back in place in 1924. (fn. 63)

The only complete medieval house yet identified, no. 46, High Street, built c. 1500, is entirely timber-framed. It was planned as a two-bayed open hall parallel to the street and at the southern end another bay of accommodation on two storeys. (fn. 64) In the early 17th century the building was encased in coursed limestone rubble and stone-mullioned ovolo-moulded windows were added. A floor and a chimney were inserted into the hall and a north-west wing was built, probably replacing a detached kitchen. (fn. 65) If no. 46 is typical, the High Street would have been lined with timber-framed buildings in the Middle Ages, an appearance which was altered when stone façades became more usual in the 17th century. (fn. 66) Other medieval survivals may include a long timber-framed jettied wing to the rear of no. 35, (fn. 67) the 1½ storeyed house at the north east corner of St Sampson's churchyard which may be a late medieval house recased in stone, and the White Horse inn at the corner of Bath Road, (fn. 68) rebuilt in the early 19th century.

John Aubrey, writing in the later 17th century, suggested that Cricklade once had a market cross, resembling the 15th-century covered market crosses at Salisbury and Malmesbury, bearing the arms of a branch of the Hungerford family, (fn. 69) although there is no evidence of this. A market house stood in High Street to the north of Calcutt Street; it was open on the ground floor with an enclosed room above, supported on 10 stone pillars, and was demolished in 1814. (fn. 70) The pillars were said to survive as part of a farm building south of the town. (fn. 71) John Britton, writing in or before 1814, said that it had been built in 1569, claiming to have seen the date inscribed on the south-east side of the building. (fn. 72) There is no other record of such an inscription, (fn. 73) although a flying buttress supporting a south-east chapel of St Sampson's church does bear the date 1569, and Britton may have transposed his information about the market house and the buttress. It is more likely that the market house was built c. 1663, a period in which other market houses were built in Wiltshire and a new market for Cricklade was granted. (fn. 74) Perhaps mistaking Aubrey's statement about a covered cross for a reference to the market house, it has been claimed that both the market house at Cricklade and the south-east chapel of St Sampson's church were built by members of the Hungerford family of Down Ampney (Glos.); (fn. 75) there is no evidence to support either claim.

Two medieval farmsteads stood within the town's fortifications. In the north-east corner there were probably buildings on the site of Abingdon Court Farm before the town was built, and in the south-west corner the demesne court was probably held in the buildings on the site of Parsonage Farm in the 12th century. (fn. 76) Parsonage Farm included a large stone barn, probably of the late 15th or early 16th century, which came to be called a tithe barn. (fn. 77)

Immediately north of the town bridge a hospital dedicated to St John the Baptist, (fn. 78) was built probably in the 1220s. It was founded by Warin, a chaplain of the king, who was at Cricklade in 1227 and keeper of the hospital in 1231, to provide a home for poor and incapacitated priests and rest and refreshment to poor travellers. The prior of the hospital was to lead a regular life and wear a regular habit. The hospital may not have flourished immediately and some of the buildings intended for it had not been erected by 1237. (fn. 79) It came to be endowed with land, tenements, and tithes at Cricklade. (fn. 80) In 1535 its net income, £4 15s., was low; (fn. 81) in 1548 the prior lived in Dorset and the hospital was presumably not making the prescribed provisions. (fn. 82) The buildings and endowments were sold by the Crown to a mercer of Cricklade in 1550, (fn. 83) and some may have been put to commercial use.

A house of two storeys and attics and at least two units was built on part of the hospital site in the early 17th-century. Its west end survives as no. 2 the Priory, attached to no. 3 the Priory, a six-bayed single-pile range of two storeys and attics, which has a heavy collar truss roof and timber mullioned and transomed windows on the north, built c. 1700, perhaps replacing earlier fabric. Part of the surround of a large medieval window survives in the east wall of the house, likely to have belonged to the hospital buildings, which John Aubrey, writing in the 1660s, described as the east window of the chapel. (fn. 84) In the 17th century and later paupers were probably housed in a building on the east side of High Street which consisted of several tenements on the site of what is now 91 High Street. In 1840 the building was called a hospital, (fn. 85) a description which later led to the apparently mistaken belief that it was part of St John's hospital. (fn. 86)

17TH AND 18TH CENTURIES

During the Civil War, Cricklade found itself between the much-contested garrisons of Cirencester, Highworth and Malmsbury. Both of the town's Long Parliament MPs, Thomas Hodges and Robert Jenner, were supporters of Parliament. (fn. 87) Although Cricklade avoided much of the fighting, parliamentary forces quartered at Cricklade were attacked, and 40 of their horses were captured by royalists led by Sir Thomas Nott, (fn. 88) who may have been based at Great Lodge in Braydon forest. (fn. 89) The town did not escape the general dislocation of the period. In 1646, the inhabitants complained that, because of the war and the closure of the market following an outbreak of plague, they had been forced to maintain hundreds of poor and sick people for seven months. (fn. 90)

The town was not adversely affected by the events of the mid 17th century, however, and it continued to grow slowly. The street plan of Cricklade was little altered in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, but nearly all the buildings standing in 1600 were replaced or refronted. (fn. 91) High Street expanded along the roads leading north and south from it, northwards apparently from the 17th century and southwards apparently in the 18th, where a row of c. six houses was built on the west side of the road. (fn. 92) Port mill, which probably stood near the town bridge, is not known to have been standing after the 16th century. (fn. 93) The pool which remained near the bridge was used for washing horses and presumably for loading and unloading boats; (fn. 94) the bridge was rebuilt or partially rebuilt in the 1760s. (fn. 95)

Only three new houses of the early 17th century are recognizable from their external appearance, a 17thcentury wing of Abingdon Court Farm, no. 2, part of the Priory Brook House, no. 72 at the north end of High Street on the east side incorporates at its north end the gabled three-storeyed remains of a larger house which faced north and had timber-mullioned windows, from which survive the decorated lintels of a local type; its east rooms on all three floors were heated by a south chimney stack, against which a staircase rose. Later in the century a four-bayed south-western range was built on a slightly different alignment and a new west façade was applied across both old and new blocks to make a fine street front finished in squared and dressed stone with a high plinth and continuous dripmoulds. In c. 1700 the house was given a pitched roof with dormers, a deep moulded eaves cornice, and sashed windows.

A house probably dating from the early 17th century stood on the site of the rectory house of St Mary's church, (fn. 96) a north part of Alkerton House, 114 High Street, may represent the cross wing of another, (fn. 97) and a room with cross beams in the White Lion, 50 High Street, may be of the same period. More modest 17thcentury houses apparently include a 1½-storeyed one hidden by the later façade of 49 High Street, and a small house adjoining the north-east corner of St Sampson's churchyard. (fn. 98) Bath Road, which ran between the plots of what are now 31 and 32 High Street, (fn. 99) on each of which stood an inn, came to be lined with large outbuildings of the inns, perhaps as early as the 17th century. (fn. 100) Further west, and adjoining St Sampson's churchyard, the school was built in 1652. In 1726–7 it was converted to a parochial workhouse, and it was separated from the traffic in Bath Road in 1744 when a wall was built around it. (fn. 101)

The first half of the 18th century was a phase of vigorous building activity. At least 3 dozen houses survive from that period including some of the grandest. In July 1723 there was a serious fire in which 20 dwellings were destroyed. Collections were being made to relieve the 'loss by fire' suffered at Cricklade, as far away as Long Burton, Dorset, in 1724. (fn. 102) Although two houses in Bath Road are known to have burned down, (fn. 103) the survival of a timber-framed inn at the corner of Bath Road and High Street (fn. 104) suggests that the seat of the fire was elsewhere. It may have been in the north part of High Street between the White Lion and Abingdon Court Lane where several houses on each side of the street seem to have been built in the mid 18th century. Knoll Cottage no. 71, the Old Manor House no. 73, and the Red Lion no. 74, were all built in the early to mid 18th century.

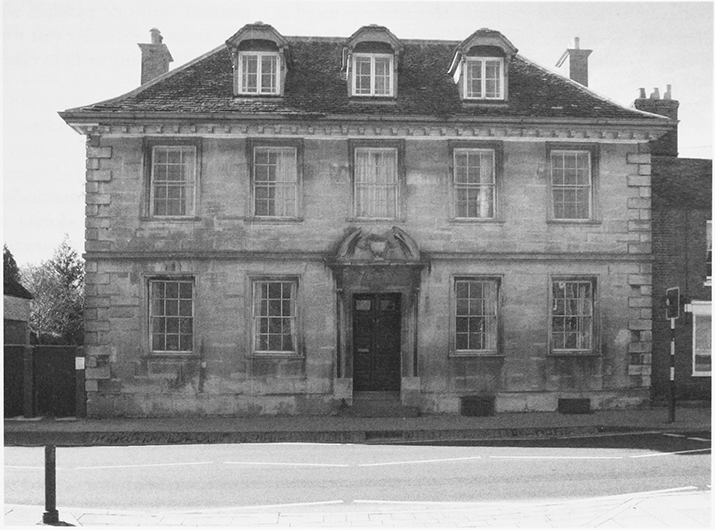

In the 18th century the favoured location seems to have been at the south end of High Street near St Sampson's church and the manor house, where several large houses were built or refronted. The manor house was rebuilt c. 1700 as a two-storeyed stone house with dormers in a hipped roof. No. 23, a smaller but similarly sophisticated detached house, was built on a large plot on the west side of High Street in 1708, (fn. 105) for Richard Byrt, a town bailiff of the late 17th century. His grandson, Morgan Byrt, also served regularly as bailiff between 1770 and 1814, and was implicated in the controversial election of 1780 which led to the reform of Cricklade's franchise two years later. (fn. 106) The house is of five bays and two storeys with attics, has a compact double-pile plan, which includes services, under a hipped roof in which c. 1880 there were, as in the Hermitage, dormers with alternating pediments. (fn. 107) The symmetrical street façade is faced with dressed ashlar with rusticated quoins, modillion eaves course, band course, and swan-necked pediment over the door. The rear façade still retains cross-mullioned windows and a large integral kitchen chimney stack. Several other façades of this period were designed in similar style but on a smaller scale, and were built of coursed rubble, rendered, with dressed stone restricted to rusticated quoins and band courses; for example, nos 26 and 27; the plain no. 28, formerly the King's Head; nos 35–6 a pair with two-bayed façades; further north no. 38, White Horse Vale social club in 2004, detached and of four bays; and nos 45 and 47, two independent but joined houses. Two similar small houses nos 33–4, were built at the west end of Calcutt Street along the west side. A large house called the Hermitage was built off the south side of Calcutt Street c. 1700; it was of two storeys and, fronted with ashlar and having dormers with alternating pediments, of a sophisticated design. (fn. 108) On Calcutt Street two rows of houses and cottages had been built by 1775, (fn. 109) some of which survive. (fn. 110) On the north side no. 5 is a house of two storeys and attics and no. 7 was an inn, (fn. 111) and on the south side nos 33 and 34 are a pair also of two storeys and attics. Some of these houses stood inside the town's fortifications and others stood outside. (fn. 112) The right of the householders outside to vote in parliamentary elections was disputed in 1776, when it was alleged that the houses had been built to create votes. In 1830 the outbuildings of the Hermitage may have been used for farming. (fn. 113)

4. No. 23 High Street, built by Richard Byrt in 1708, and then one of the most fashionable houses in the town. A boarding school for girls 1833–78, it has become a private house again.

Humbler and plainer houses, many of only two bays, were built in High Street from its middle section up to its north end and at the east end of of Calcutt Street. Although most, including the Red Lion, were twostoreyed, more than a dozen were single-storeyed cottages with garrets in the roof, some of which have been raised to two storeys, for example nos 56 and the pair at nos 87–8. Very few seem to have incorporated older property, suggesting that this end of High Street was badly affected by the fire of 1723.

In the late 18th century less building took place. The south end of High Street retained its prestige. Facing the Byrt residence is no. 112, a smaller house of comparable quality, of five bays and two storeys with attics, later converted into a bank. No. 114, Alkerton House, was occupied by the Pleydell family until 1775, when it was bought by Arnold Nesbitt, the new lord of the manor; a plain four-bayed and two-storeyed south range was added and the north range was refronted to match it. The house was owned by successive lords of the manor until Joseph Pitt sold it to the surgeon Thomas Taylor c. 1842. (fn. 114) No. 109, Danvers House, was given a new street façade with Venetian-style windows in a recessed surround, an unusually ambitious motif in Cricklade. As there was no back lane along this stretch of High Street, Danvers House and its neighbours were planned with side passages within the forebuilding to give access to extensive rear wings. There was also some minor rebuilding work in other parts of High Street.

MODERN TOWN

THE 19TH CENTURY

Building activity seems to have revived a little in the early 19th century: older houses were refronted and commercial properties were enlarged or rebuilt. The market house in High Street was demolished in 1814, (fn. 115) the cross was removed from High Street to St Sampson's churchyard probably between 1817 and 1820, (fn. 116) and major improvements to the surface of High Street were made between 1814 and c. 1830. (fn. 117) By 1840 tannery and foundry buildings stood between Brook House and the river, (fn. 118) and the buildings of the foundry were replaced by a school built in 1860. The town bridge was rebuilt in 1854, (fn. 119) and in 1870 a Nonconformist chapel was built immediately north of it.

Although no new house of high social status was erected several large houses were modernized. Alkerton House was given a porch with Tuscan columns, and no. 3, part of the Priory was altered: a range of three bays and three storeys, resembling a house but partly in industrial use, was added to the north side and incorporated a taking-in door in the north gable; some buildings on the site were used for tanning and gloving and for fellmongering in the early 19th century, (fn. 120) and one was used as a Nonconformist meeting house. (fn. 121)

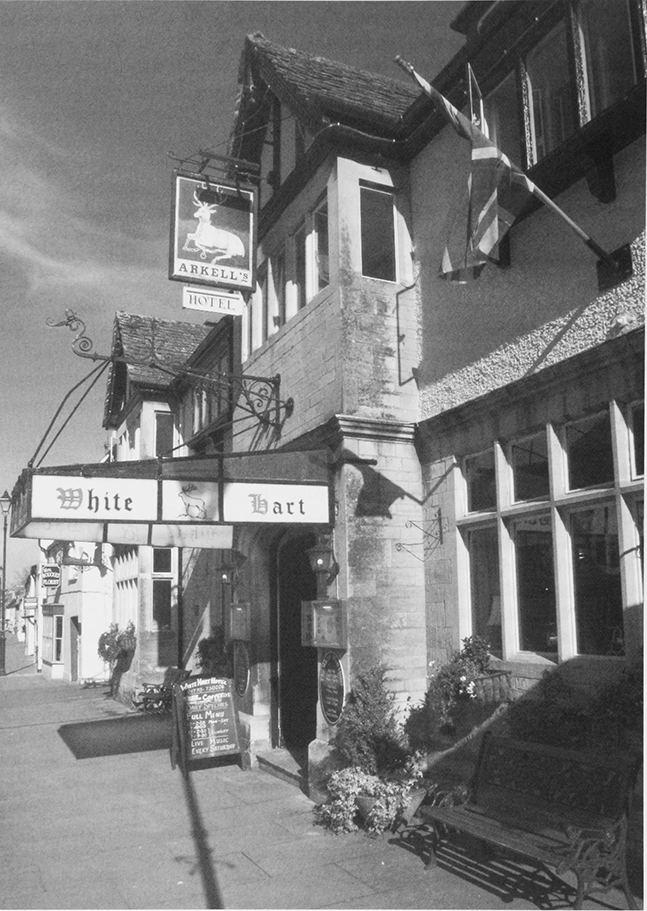

New building in High Street and Calcutt Street replaced older buildings; including 75–6 High Street, opposite the chancel of St Mary's church; and no. 30, previously the location of White's chemist's shop, which was replaced after the building was burnt down in 1893. (fn. 122) Some new houses incorporated shops, for example no. 29, or had new shopfronts fitted, like the 18th-century houses at nos 31 and 107. The White Horse, later the Vale Hotel, was rebuilt in the earlier 19th century in an elegant style, stables and other large outbuildings were erected behind the Old Bear, and the Red Lion was extended. (fn. 123) The Three Horseshoes may have been converted from existing buildings and given its carriage arch, and the White Hart was rebuilt in 1890 in a many gabled Domestic-Revival style that left it the largest and most elaborate commercial building in High Street. A privately-owned town hall was built at the south end of High Street in 1861, and terraces of houses built on the west side during the late 18th and the 19th centuries linked the street to houses built outside the line of the fortifications in the 18th century. (fn. 124) To celebrate Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee a clock mounted on a decorated cast-iron pillar was erected at the crossroads; it was unveiled in 1898, lit by gas, and painted in 1900. (fn. 125)

In Calcutt Street, a Nonconformist meeting house was built in 1798–9, and that was enlarged and two more were built in the 19th century. Most 19th-century building, however, was of small houses on new sites or to replace existing buildings. The Hermitage was transformed into the largest house in the town and renamed Manor House: in 1875 it consisted of a rectangular block with a long east wing; by 1898 it had been rebuilt in more than one phase as a much larger Lplan house. (fn. 126) In 1902 the house had a seven-bayed façade, which replicated the design of the Hermitage and to which a grand porch had been added, and an east bay with large mullioned and transomed windows; in that year the façade was extended westwards to nine bays and a further west bay was added. (fn. 127)

In Bath Road the workhouse was enlarged c. 1800, but later reduced and restored to work as a school in the early 1840s. (fn. 128) St Sampson's parish housed paupers in a pair of cottages nearby, but these were demolished between 1842 and 1875. (fn. 129) A fire engine house was built in 1858, (fn. 130) stables and kennels were built for the Vale of the White Horse hunt probably in the mid 1880s, and a cemetery was opened in 1900. West of the fortifications, buildings on waste ground on the south side of the road were replaced by a terrace of four cottages built in the mid 19th century. (fn. 131)

In the 19th century, five lanes led east and west between buildings in High Street; Red Lion Lane and Abingdon Court Lane on the east side, Rectory Lane, Mutton (later Gas) Lane, and Church Street (later Church Lane) on the west. Red Lion Lane contained the outbuildings of the Red Lion and several cottages; (fn. 132) houses in Abingdon Court Lane (fn. 133) were added to between 1840 and 1875, (fn. 134) whilst buildings in Rectory Lane were replaced with terraces of small cottages. (fn. 135) In Mutton Lane, which followed the boundary between St Sampson's and St Mary's parishes, (fn. 136) buildings erected to the south between 1842 and 1875 included a school apparently open in 1859. At the west end of the lane a gasworks was built probably c. 1859. (fn. 137) Church Street, which leads to St Sampson's churchyard, was lined with buildings, one of which, a small house of one storey and attic built of stone, probably dates from the 17th century. (fn. 138)

The two lanes leading north from Calcutt Street were Ridler's (later Grubbs and then Thames) Lane, leading to Abingdon Court Farm, and Horsefair Lane, which gave access to the burghal plots of 80–105 High Street. Few buildings fronted it in 1830, although some had been erected in the lane itself where it widened at its north and south ends. On many of the burghal plots buildings were erected between 1830 and 1875, presumably for commercial or industrial use.

Squatter Settlements

Known as the Forty and Spital Lane, two squatter settlements grew up on waste ground on the outskirts of the town. In Spital Lane, off Calcutt Street, several buildings standing c. 1800 were replaced by houses built in the 19th century. (fn. 139) At the Forty, beside the Purton road, a dozen cottages and houses had been built by c. 1800, (fn. 140) two of the oldest possibly dating from the 17th century, and by 1898 the suburb had grown. (fn. 141) Some 19th-century buildings were for industrial use, but most were low quality houses and many were demolished or replaced in the 20th century. The Forty was extended southwards when houses and bungalows were built on Giles Avenue off the west side of the Purton road c. 1950; (fn. 142) and a telephone exchange was also built on the east side of the road.

The 20th Century

In 1914 housing was concentrated in High Street, Calcutt Street, Abingdon Court Lane, Grubbs Lane, and at the Forty, (fn. 143) and the town grew little between then and c. 1950. After 1918 there was little commercial or public building in the centre of the town. In High Street a few properties were replaced by low quality shops and houses; a police station, no. 91, was built in 1921–2 and refronted in 1962; and in 1933 a new town hall was built and the Old Bear rebuilt in a late pared-down Arts-andCrafts style. There was some new building in the lanes off High Street: a house was refronted in Rectory Lane in 1927; in Church Lane a small house was built in 1907 and a large house called the Croft replaced a line of small buildings in 1913. (fn. 144)

In the Second World War eight Nissen huts were erected south of the town hall, mainly used by the Army Cadet Corps, the NAAFI, and the Red Cross; and both the Red Lion and the White Hart were requisitioned by the War Department. (fn. 145) In the mid 20th century the market held in High Street ceased, (fn. 146) and in the later 20th century the number of shops, inns and public houses fell and manufacturing ceased. Traffic conditions were improved by the widening of the junction of High Street and Calcutt Street in 1968; (fn. 147) a new road built in 1970 along the line of the railway to the south of the town replaced Bath Road as the route to Malmesbury, and a road built along the line of Ermin Street in 1975 bypassed the town to the north-east. After the opening of the new road to Malmesbury, Bath Road was closed to vehicles between St Sampson's church and the school.

Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council was responsible for new building on the outskirts of the town, beginning in 1921–2 with a row of 16 brick semi-detached houses, built on Common Hill, the part of the Malmesbury road west of the town. (fn. 148) In 1932 the council constructed eight semi-detached houses more cheaply of concrete blocks at Fairview, north of Calcutt Street and east of Spital Lane. (fn. 149) They are of a type built throughout the rural district.

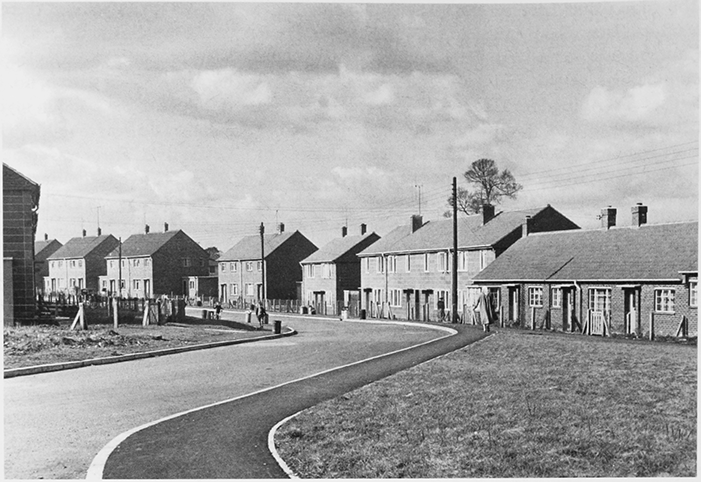

Most later 20th century growth was west of the town. In Bath Road stables and kennels were replaced by new housing in the early 1950s: between 1953 and 1957 the council built over 100 semi-detached brick houses and bungalows in Culverhay estate, north of Bath Road and west of the cemetery. (fn. 150) The plots were generous and in 1968–9 Pike House Close was built on the long back gardens of one of the streets. (fn. 151) A new school was built to the east of the cemetery in 1959. South of Bath Road new housing and a new fire station were built in the early 1960s; Parsonage Farm, requisitioned by the War Department in the Second World War, and the tithe barn were demolished in 1964 and were replaced by new housing and a temporary public library. (fn. 152) Housing density was much greater on the Parsonage Farm estate, built in the 1970s, which consisted of courts of brown brick terraced houses, plain blocks of flats, and an old people's home near St Sampson's church. (fn. 153) The Gasworks was replaced by housing in Gas Lane, and houses were also built in Portwell c. 1992. (fn. 154)

5. The bungalows and houses of the Culverhey estate, built in the 1950s by the rural district council, the start of the post-war westwards expansion of Cricklade.

West of the town speculative building of several hundred new houses on private estates began in the 1960s. South of Bath Road, Doubledays, an estate of detached bungalows was built in 1961–2; (fn. 155) from 1964–7 plain semi-detached houses were built at Pauls Croft between the town's fortifications and the railway line at the south end of High Street; (fn. 156) in 1972–3 Waylands, an estate of Scandinavian-style houses hung with green clay tiles was built east of High Street and north of the town's fortifications, which divided Waylands from Pauls Croft to the south; (fn. 157) west of Doubledays Cliffords was built in 1975–6. (fn. 158) Chalet bungalows were popular and many houses had attached or integral garages and open front gardens in North American style: Bishopsfield, Deansfield, and Pittsfield were built c. 1970 south of Malmesbury Road, using a sophisticated layout with paths leading between the cul-de-sacs to St Sampson's church. (fn. 159) The houses built in the late 1970s on Hallsfield and other private estates were of plain appearance with the addition of box-like oriel windows and were closely grouped around courts. (fn. 160) A new estate approached from West Mill Lane, was built c. 1975; and neo-varnacular style was used for an estate built at North Wall in the early 1980s, partly bounded by the town's northern line fortifications, (fn. 161) and for small houses on infill sites in the town. Further expansion took place in the 1990s west of West Mill Lane, in Reeds and other roads. (fn. 162)

Development also took place in the east of the town from the mid 20th century. In Calcutt Street Manor House, formerly the Hermitage, became the Priory school in 1946 and new buildings were erected in 1947, the 1960s, and later. Cottages east of it were replaced by a commercial garage, which later closed and the converted showroom became a nursery school. About 1991 Hammonds was built between the junctions with Horsefair Lane and Thames Lane; (fn. 163) a number of individual houses were built on these lanes; (fn. 164) Manor Orchard was built on the east side of Thames Lane c. 1996; (fn. 165) and in c. 2002 the site of Abingdon Court Farm was developed. Development east of the town began in 2003 when Stockham Close was built. (fn. 166) Here there was a more varied layout of Victorian-style houses in a limited range of types and sizes, with garages or shared parking shelters.

GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS

Cricklade was apparently built c. 880 as a planned town on land, which before that date, was probably used in common by the men of Chelworth, and was therefore controlled by and subject to the lord of Chelworth. A manor of Cricklade is recorded in the 13th century, which had no other land besides that on which the town stood. Presumably from the time of the town's foundation the owners of the tenements there paid rent to successive kings. In the mid 11th century the rents from some of the tenements belonged to Cricklade church, which had probably been endowed with them by the king at its foundation. The Crown had granted away other tenements by 1086, when the king held tenements worth £5, (fn. 167) and other tenements were granted away later. The manorial court seems to have functioned as a borough court and eventually to have appointed the borough's main officials and to have been responsible for providing some public services. Other local institutions which played a significant role in local government were Wayland's charity, which from the late 16th century paid officials of the borough, the bailiff and constables, and St Sampson's vestry which appointed two surveyors of the highways.

CRICKLADE MANOR

The tenements in Cricklade were held by burghal tenure, (fn. 168) and the rents were paid to the king and to subsequent lords of the borough. By the mid 13th century the profits of lordship, comprising the rents, the tolls of markets and fairs held in the town, and the perquisites of courts held for the borough, (fn. 169) had come to be called Cricklade manor. (fn. 170)

In 1156 the rents worth £5 were held by Warin FitzGerold (d. 1159, without living issue), a chamberlain of the Exchequer. Warin's estate passed to his brother Henry FitzGerold (d. 1174–5), also a chamberlain of the Exchequer, who was succeeded by his son Warin FitzGerold. (fn. 171) About 1211 Warin's tenure of the lordship of Cricklade borough was by serjeanty, the service being that of a chamberlain in the Exchequer. (fn. 172) The estate at Cricklade was among the former demesne lands of the Crown resumed by Henry III in 1216 or 1217, but it was restored to Warin in 1217. (fn. 173) It had passed by 1224 to Warin's daughter and heir Margery (d. 1252), the widow of Baldwin de Reviers and the wife of Faukes de Breauté (d. 1226). Margery was succeeded by her grandson Baldwin de Reviers, earl of Devon and lord of the Isle of Wight (d. 1262), whose heir was his sister Isabel, the widow of William de Forz, count of Aumale. (fn. 174) In 1276 Isabel granted estates, including Cricklade manor and still held for service as a chamberlain of the Exchequer, to her attorney Adam Stratton. (fn. 175) In 1289 Cricklade manor was among the estates taken into the king's hand when Adam was charged with corruption. (fn. 176)

Margery de Reviers granted 20s. 8d. rent from Cricklade to John of Elsfield, probably c. 1247. (fn. 177) The rent descended to John's son Gilbert, whose widow Gillian married Ingram le Waleys and afterwards John de St Helen. In 1276–7 the rent, which arose from six burgages in the town, was sold by Waleys to Adam de Stratton. (fn. 178) With Cricklade manor it was taken into the king's hand in 1289. (fn. 179) In 1318–19 Gilbert's grandson Gilbert Elsfield recovered the rent from the king on the grounds that Gillian had held it only for her life, and in 1329 that Gilbert's son Gilbert returned it to the king in an exchange. (fn. 180) The rent was presumably restored to Cricklade manor.

Other rent from Cricklade had descended by 1262 from William of Aylesbury to his son Warin of Aylesbury. (fn. 181) By 1278 Warin's son William of Aylesbury had sold the rent of 19½ burgage plots to Adam Stratton. (fn. 182) It was presumably merged with Cricklade manor.

Cricklade manor passed with the Crown from 1289 to 1391. It was held as dower from 1299 by Queen Margaret (d. 1318), (fn. 183) from 1318 by Queen Isabel, who returned it to the king in 1330, (fn. 184) and from 1331 by Queen Philippa (d. 1369). (fn. 185) It was almost certainly among estates granted in 1391 to Edmund, duke of York (d. 1402), (fn. 186) and was held by Edmund's son and heir Edward, duke of York (d. 1415). (fn. 187) Edward's widow Philippa (d. 1431) held a third of it for life. (fn. 188) From 1415 Edward's lands were held in trust for his nephew Richard, duke of York (d. 1460), who had livery of his lands in 1432. (fn. 189) In 1459 the lands were forfeited when Richard was attainted, in 1460 they were restored to Richard and passed to his son Edward, duke of York, (fn. 190) and from 1461, when Edward acceded as Edward IV, to 1547 Cricklade manor again passed with the Crown. From 1461 the manor was held for life by Cecily (d. 1495), the widow of Richard, duke of York, (fn. 191) from 1495 to 1547 it was part of the jointure of queens consort, and it was held by Catherine Parr at Henry VIII's death. (fn. 192) In 1547 the reversion was granted to Catherine's husband Thomas Seymour, Lord Seymour, who held the manor from Catherine's death in 1548 until he was attainted in 1549. (fn. 193)

From 1549 Cricklade manor was again held by the Crown, until it was granted to George and Thomas Whitmore in 1611. (fn. 194) In 1618 George sold it to Edmund Maskelyne (fn. 195) (d. 1630) of Purton, the lord of Chelworth Cricklade manor and owner of an estate in Purton. Maskelyne was succeeded by his son Nevil (fn. 196) (d. 1679), he by his grandson Nevil Maskelyne (fn. 197) (d. 1711), and he by his son Nevil. In 1718 Nevil sold the manor to William Gore (d. 1739) of Tring (Herts.), who was succeeded by his son Charles. (fn. 198)

In the 18th century Cricklade manor was useful to those who sought to influence parliamentary elections at Cricklade, and in the later 18th century and earlier 19th successive lords of the manor also owned many tenements in the town. In 1762 Charles Gore sold the manor to George Prescott. In 1763 Prescott sold it to Arnold Nesbitt (d. 1779, without issue), who devised it to trustees, and in 1780 the trustees contracted to sell it to Paul Benfield, a trader in India, who entered on it in that year. In 1790 Chancery ordered that the contract should be observed, and in 1791 the sale to Benfield was completed and Benfield sold the manor to Henry Herbert, Lord Porchester (earl of Carnarvon from 1793, d. 1811). The manor descended to Lord Carnarvon's son Henry, Lord Carnarvon, who sold it in 1815 to Joseph Pitt (d. 1842). Pitt devised it to his son Joseph, who sold it in 1842, separately from Pitt's many tenements in the town, to Joseph Neeld. (fn. 199) Cricklade manor, then of little value, passed on Neeld's death in 1856 to his brother John (created a baronet in 1859, d. 1891), and it passed in turn to Sir John's sons Sir Algernon Neeld Bt (d. 1900), and Sir Audley Neeld Bt (d. 1941). (fn. 200)

OTHER ESTATES

In 1008 King Æthelred gave a praediolum or a haga, probably a tenement in the town, to Abingdon abbey (Berks. later Oxon.), (fn. 201) and later in the Middle Ages burgage plots were held by Cirencester abbey (Glos.), Glastonbury abbey (Som.), Godstow abbey (Oxon.), Shaftesbury abbey (Dorset), Bradenstoke priory, Malmesbury abbey, and St John's hospital at Cricklade. (fn. 202) By 1086 holdings of several burgages had been accumulated: Alfred of Marlborough held seven, the king held six which had been Gytha's in 1066, St Peter's abbey, Winchester (the New Minster), also held six, the bishop of Salisbury held five, Odo of Winchester held three, and Robert held three from Humphrey de Lisle. (fn. 203)

By 1779, as part of his attempt to control parliamentary elections, Arnold Nesbitt, MP for Cricklade and the lord of Cricklade manor, had bought c. 45 houses in the town. The tenements passed with the manor to Paul Benfield. In 1815 Lord Carnarvon sold c. 36 tenements with the manor to Joseph Pitt, and in the 1830s Pitt owned 66 or more tenements in the town. (fn. 204) The tenements were apparently sold individually from 1842 by Pitt's successor in title. (fn. 205)

THE BOROUGH AND ITS COURTS

The freedom of the burgesses of Cricklade from toll and passage was granted or confirmed in the later 12th century, and a guarantee that their goods would not be seized for a debt in respect of which they were not sureties or the principal debtors was given in 1267. (fn. 206) Those liberties were confirmed several times, (fn. 207) but the burgesses acquired no additional liberty and the borough was never self-governing.

The lord of Cricklade manor, which comprised only Cricklade borough, was also the lord of Cricklade hundred and enjoyed liberties which brought in income, defined in the 1280s as execution and return of writs, pleas of vee de naam, concerning goods confiscated as security, gallows, pillory, tumbril, and the assize of bread and of ale. The burgesses owed suit to the hundred, (fn. 208) the suit of other men was apparently withdrawn by their lords, and probably from the 13th century the three-weekly hundred court and the twiceyearly view dealt only with the business of Cricklade borough. The court and the view of frankpledge were apparently held at regular intervals in the 15th and 16th centuries. (fn. 209) Records are extant for 1545–7, 1754, 1799, and 1807–55. In the 18th and 19th centuries the view was called the court leet and view of frankpledge of the lord of the manor of the borough and hundred of Cricklade. (fn. 210)

The court and the view were held by a visiting steward, and the lord's principal officer in the borough was the bailiff. In the mid 15th century the bailiff's main functions were to collect the rents and other payments due to the lord, presumably to conduct parliamentary elections, and probably to convene the court and the view. (fn. 211) In the mid 15th century there were two constables, whose function was presumably to keep order. (fn. 212) In the mid 16th century and almost certainly earlier there were two aldermen, an ale taster and a water bailiff. (fn. 213) In the mid 18th century the view appointed the bailiff, two aldermen, two constables, two ale tasters, two water bailiffs, and two inspectors of meat. It also appointed a crier, who was possibly responsible for convening it and for the swearing in of the jurors and officers. By 1799 the yearly appointment of aldermen and of one of the water bailiffs had ceased and the appointment of two leather sealers and a scavenger had begun. Later a hayward was appointed. One constable acted for that part of the borough in St Mary's parish, the other for that part of the borough in St Sampson's, and the same division of labour apparently governed the activities of the other officers elected in pairs. (fn. 214)

In 1267–8 and 1280–1 men of Cricklade were amerced for selling wine in a way that broke the assize. (fn. 215) In the mid 16th century neither the court nor the view was vigorous, and the offences dealt with were narrow in range and small in number. At the court pleas were made, the aldermen made occasional presentments of offences such as assault or failure to control pigs, and the ale taster presented brewers who had broken the assize. At the view the aldermen presented the offences of butchers, bakers, millers, and an innkeeper, the ale taster again presented brewers, and the presentments were affirmed and added to by a jury or what was called the whole tithing. The failure to scour a ditch and to repair a street were presented by the whole tithing in 1546. (fn. 216)

There is evidence that the court heard cases concerning the recovery of small debts until the 19th century, (fn. 217) but no direct record survives after 1547. (fn. 218) The view of frankpledge probably increased in importance in the later 16th and 17th centuries, as similar courts did elsewhere. (fn. 219) To judge from the titles of the 18th-century officers, it was responsible for good order in the borough and the regulation of the market and fairs. It dealt with apparently increasing numbers of public nuisances, and in the 18th century it defended the lord's right to the waste land in the borough. In 1754 it ordered the repair of the pitching in the streets, the removal of dung obstructing a watercourse, and the removal of a hayrick and a pigsty from the waste; in 1799 the disrepair of the streets, drains, and watercourses, and encroachments on the waste, remained the principal concerns. (fn. 220)

In the 19th century the view of frankpledge was held annually in October, from 1812 or earlier in the town hall, then the upper room of the market house, and from 1822 in the White Hart. Its main functions were to appoint officers and remedy public nuisances. In 1809 a man was amerced for allowing carts to stand in the street opposite his house and another for emptying his lime pits in front of his. In 1813 new presentments included nine resulting in orders to repair the pitching of the streets, five in orders to remove dunghills, four in orders to repair drains, and one in an order to take down a penthouse which was an encroachment on the waste; marginal notes in the record suggest that half the 20 orders were obeyed. (fn. 221)

From 1815 the view of frankpledge appointed a hayward each year and began to oversee the use in common of North meadow. The hayward was to mark animals feeding in the meadow and to impound animals found loose in the streets. (fn. 222) The view's supervision of tradesmen and the market, however, may have been in decline in the earlier 19th century. The presentment, made in 1826 (fn. 223) and often repeated, that the borough lacked the standard imperial weights and measures against which the ale tasters might compare the weights and measures used by the tradesmen and publicans of the borough may reflect continuing concern with trade in the town or, perhaps more likely, have provided an excuse for inactivity. In the 1850s an attempt by the ale tasters to inspect the measures in use at the Bear were successfully defied by the publican. (fn. 224) From 1832 no leather sealer was appointed because the duty on leather had been removed. (fn. 225) The view's concern for the maintenance, safety, and cleanliness of the streets continued. In 1835 it ordered the demolition of the Bear because it was dilapidated and dangerous, in 1842 it ordered the nuisance caused by a privy in Calcutt Street to be remedied, and in 1848 it ordered the feoffees of the Waylands charity to erect a wall or fence on the bridge over the Thames. (fn. 226)

About 1840 the view met at 11 a.m., the jurors having been summoned a week in advance on a warrant issued by the bailiff and delivered by the crier. The officers were chosen, walked about the town, reported nuisances, which were recorded, and went to dinner. The parties who were presented for causing nuisances were notified, and thereafter the bailiff, the crier, and the jurors went to dinner. (fn. 227) From 1852 the view did no more than appoint officers and recite former orders, (fn. 228) and in 1858 it was said to be shunned by the inhabitants and to be a mockery. There was apparently no further meeting of the view until 1899, when it met to delegate the management of North meadow to the new parish council. In 1919 the council declined the management of the meadow, and the view may have met occasionally thereafter. (fn. 229) It met in 1942, had not met again by c. 1960, (fn. 230) and met in 1966 and not again until 1976. (fn. 231) In the early 21st century it was again meeting to supervise the grazing of North meadow. (fn. 232)

Petty Sessions

They were held monthly at Cricklade in the early 19th century, presumably in one of the inns. (fn. 233) From 1862 they were held fortnightly and later monthly in the town hall. (fn. 234) The sessions were held in the new town hall from 1933 and ceased in 1993. (fn. 235)

PAROCHIAL GOVERNMENT

Parish government was concerned primarily with administering amenities for the townspeople. The parishes of St Sampson and St Mary each relieved its own poor from the 16th century to 1835. Each was responsible for maintaining its highways, but was relieved of much of the financial burden by the Waylands charity. Both parishes joined Cricklade and Wootton Bassett poor-law union at its formation in 1835 and remained part of it as it became a rural sanitary authority and a rural district. (fn. 236) A council for each parish met 1894–9 and for the united parish from 1899; none had much power. In 1974 Cricklade parish became part of North Wiltshire district. (fn. 237)

ST SAMPSON'S PARISH

Poor relief

Although the churchwardens were still

giving money to the needy in the 1670s, (fn. 238) by 1634 it had

become the practice for the parish to appoint four

overseers. (fn. 239) By 1689 the vestry had asserted its close

control over the management of poor relief, approving

all new recipients and any increased payments. In the

mid 18th century it met about once a month and was

attended by no more than five members, who assessed

applications for relief. A select vestry was appointed in

1819, and a new select vestry met three times in 1827.

Between 1689 and 1835 the vestry took and authorized

measures to relieve the poor at the least cost to the

parish, the measures becoming more diverse as the

number and cost of paupers grew. (fn. 240) In 1775–6 £239 was

spent on the poor, in the three years ending at Easter

1785 an average of £395. In 1802–3, when the poor rate

was low for the hundred, £721 was spent and included

the cost of relieving 117 non-parishioners, presumably

travellers on the London–Gloucester road. (fn. 241) From

1813–14 to 1834–5 expenditure exceeded £1,000 in all but

two years and exceeded £2,000 in three. (fn. 242)

The overseers were chosen from the ratepayers and, subject to the vestry, levied rates and relieved the poor. In the 1750s two acted for the urban part of the parish and two for the remainder; by the 1790s each overseer served for 13 weeks throughout the parish. (fn. 243) From 1821 the overseers' work was limited to levying the poor rate, and a salaried assistant overseer administered the dayto-day relief of the poor. In 1829–30 this work and the levying of the rates was done by a salaried deputy overseer, who was also master of the workhouse, and there was a salaried assistant overseer; from 1830 the deputy overseer administered the day-to-day relief, there was a master of the workhouse, and there was no assistant overseer. Beadles were appointed in 1760 and 1828: it is not clear whether there was one in office in the intervening period. In 1834 the beadle was paid 10s. a week; the office was abolished in 1835. (fn. 244)

6. Jenner's Hall, built as a school in 1652 with Robert Jenner's endowment. Seen from St Sampson's churchyard with, in the foreground, a 14th-century cross moved there in the 19th century.

The parish provided housing and a workhouse, gave weekly cash doles, and made many ad hoc payments to the poor. By the late 17th century paupers of St Sampson's were housed in part of a building called an almshouse in St Mary's parish, probably the building on High Street later called the hospital. (fn. 245) In 1711 St Sampson's housed paupers in tenements it owned, and by 1719 it had begun to house them in Jenner's school, which it converted to a workhouse in 1726–7. (fn. 246) The parish obtained other tenements, and in 1835 it housed 33 or more paupers in tenements held on lease. It surrendered all its leases in 1836, and its seven cottages were sold in 1840–1. (fn. 247) The vestry tried to find work for able-bodied paupers outside the workhouse. It promoted cloth making in the 1750s by employing a spinning master and giving pairs of cards to paupers; (fn. 248) in 1818 any wages earned by those who received cash doles were kept by the overseers to reduce the rate; in 1819 men could be set to work on improving the land of the Hundred Acres charity; in 1824 unemployed labourers were required to mend roads, (fn. 249) and in 1833 an attempt was made to provide work for them on farms. (fn. 250) The parish paid for apprenticeships (fn. 251) and in the 1820s and 1830s paid the passage of poor parishioners who emigrated to America. In 1830 the parish agreed to pay two doctors £25 a year to provide medical services for the poor, including surgery and midwifery, and to provide medicine and vaccination, except during epidemics. (fn. 252)

Jenner's school, in use as a poorhouse from 1719, was converted into a workhouse in 1726–7. A salaried governor was appointed and in 1728 the overseers bought 100 yd. of serge, presumably to clothe the inmates. (fn. 253) Arrangements for managing the workhouse varied little. In 1740 a woman was appointed with a salary of £2 a year, and for 2s. a week for each inmate she provided food, drink, candles, and soap for the inmates, and washed and mended their clothes. The parish provided the inmates' coal and, when necessary, new clothes. A master was appointed on similar terms in 1744. (fn. 254) The parish enlarged the workhouse to more than double its size in the early 19th century. (fn. 255) There were 28 adults and children in the workhouse in 1802–3, an average of 35 from 1812–13 to 1814–15, (fn. 256) and apparently c. 30 in the earlier 1830s. (fn. 257)

In 1819 the master's allowance was increased to 3s. a week for each inmate, but he was obliged to feed the inmates with meat three days a week and with bread and cheese on the other days; he also kept the profits of the inmates' labour, and lived with his wife in the workhouse. (fn. 258) The inmates were required to attend divine service. In 1827 the vestry ordered that the doors of the workhouse should be locked at 8 p.m. in winter, at 9 p.m. in summer; the inmates were to be given a hot dinner on Sundays and on one other day of the week. (fn. 259) As an experiment the parish managed the workhouse for a month in 1832 without a master, finding that it cost 3s. 4½d. a week to maintain each inmate. It therefore appointed a mistress with a salary of £12 p.a. and a weekly allowance of 2s. 4d. per inmate, and allowed her to keep the profits of the inmates' labour. The parish agreed to keep the number of inmates up to 30 until November 1835, when control of the workhouse passed to the poor-law union, and the buildings were used as a school once more from the 1840s. (fn. 260)

In 1634, following the disafforestation of Braydon forest, c. 100 a. of the Crown's land in the forest was placed in trust for the poor of Cricklade and Chelworth, in lieu of common rights they had lost. The Crown retained c. 2,000 a. in St Sampson's parish and the tenants claimed this was ample provision for the poor and refused to pay the poor rate. (fn. 261) In 1636 the Wiltshire justices ordered them to pay; the court of the Exchequer denied their liability to do so. Although such orders and denials were repeated in 1675, 1705, and 1773, (fn. 262) by 1689 the Crown's lessees or their undertenants had begun to pay rates. (fn. 263) They possibly did so in response to arguments put forward in 1670 that to resist might cost more than the tax and that only by paying could the Crown guarantee peaceful enjoyment of its land to the tenants. (fn. 264) Equally grudgingly the parish accepted its liability to relieve the poor living or born on the Crown's land. To do so it sought help in 1709 and 1715 from St Mary's parish and in 1741 from the trustees holding the 100 a., each time apparently in vain. (fn. 265)

Highways

The Waylands charity maintained the

highways in and about Cricklade from 1566–7 to the

20th century, thus relieving St Sampson's and St Mary's

parishes of much of the cost. (fn. 266) From the late 17th

century St Sampson's appointed two surveyors of

highways, one for the borough and one for the rest of

the parish. (fn. 267) Rates were collected from the early 19th

century, a salaried assistant surveyor was employed

until 1851. (fn. 268) Widhill, although part of the parish, was not

subject to St Sampson's highways rate, appointing its

own surveyor to maintain its own highways. (fn. 269)

At the disafforestation of Braydon forest the Crown's commissioners marked out 8–9 miles of roads across the forest, and in 1630 the court of the Exchequer allotted 150 a. for their courses across what remained the Crown's land in St Sampson's and Purton parishes. The court also ordered that the roads were to be maintained by those whose land they crossed. Although in the allotment of portions of the 150 a. to each of the roads there was a dispute whether the size of the allotment should be in proportion not only to the length of the road but also to the condition of the soil under it and the frequency with which it was used, the freedom of St Sampson's parish from obligation to repair the roads was apparently unchallenged. (fn. 270) That freedom was confirmed in 1823 when the parish was acquitted on an indictment of not repairing a road through the former forest. (fn. 271) Roads in those parts of the forest owned by, or allotted to, others than the Crown in 1630 were apparently maintained by the parish. A third surveyor, for Braydon, chosen by the parish in the 1840s and 1850s, was presumably responsible for them. (fn. 272)

Cricklade highway district was formed in 1864; (fn. 273) from then the district's board maintained the highways, and the parish merely elected waywardens to the board and raised a rate to pay for the work. (fn. 274)

St Mary's Parish

The parish had two overseers of the poor in 1634. (fn. 275) Neither their account books, nor the minute books of the vestry before 1865, are extant. (fn. 276) The parish spent £51 on the poor in 1775–6, an average of £63 in the three years starting at Easter 1782. The poor rate was very high for the hundred in 1802–3, when £166 was spent on relieving 13 adults and 9 children permanently and 19 people occasionally; all relief was outdoor. (fn. 277) The parish spent £238 on maintaining the poor in 1812–13 and £100–£200 a year between then and 1823–4. (fn. 278) Thereafter spending again rose. From 1824–5 to 1828–9 it was three times over £200, and from 1829–30 to 1833–4 three times over £300. (fn. 279)

St Mary's parish did not have a workhouse, although it may have housed its paupers in part of the almshouse used by St Sampson's parish. (fn. 280) By 1813 the parish had a poorhouse, which in 1830 was the house now called the Old Manor House at the north end of High Street. (fn. 281)

United Parish

The councils of St Sampson's and St Mary's parishes met for the first time on 31 December 1894, when St Mary's declared itself unwilling to merge with St Sampson's. In 1897, St Sampson's petitioned the county council for amalgamation, and following an enquiry, the two parishes were united as Cricklade parish in 1899. (fn. 282) The new parish council, which at first met monthly, accepted the management of North meadow in 1899; its clerk was appointed hayward and an underhayward was appointed to mark cattle and sheep. (fn. 283) The council resigned the management in 1919. (fn. 284) Sitting as a burial board it managed Cricklade cemetery, and it paid for the services of a fire brigade from 1936 to 1947. A coat of arms was granted to the council in 1948, (fn. 285) which from 1974 was called a town council. (fn. 286)

WAYLAND'S CHARITY

The income from an estate known as the Wayland's charity was used from the 16th century by the bailiff and constables of the borough to maintain the highways of both St Sampson's and St Mary's parishes. The charity owned an estate which had belonged to a chantry in St Sampson's church which was suppressed in 1547, then comprising of c. 15 cottages and houses in the town. In 1566 the Crown sold the estate to William Grice and Charles Newcommen, who sold it to leading townspeople in 1566–7; this appears to have been the establishment of the charity. (fn. 287) The court of Chancery ordered the appointment of new trustees in 1746, (fn. 288) and again in 1836; (fn. 289) and from 1866 the charity's estate was vested in the Official Trustee. The Charity Commission ordered the appointment of new trustees in 1882, and Schemes of that year and 1893 regulated the management of the charity. Under a Scheme of 1903 there were 12 trustees: two ex officio (the bailiff and the county councillor representing Cricklade), seven representing the parish, rural district, and county councils, and three co-opted. (fn. 290)

The charity's estate consisted mainly of tenements in the town and a ½ yardland at Chelworth. (fn. 291) Allotments were made to the trustees at the inclosures of 1788 and c. 1816, (fn. 292) and in 1833–4 the estate comprised 51 a. of pasture and c. 30 houses and cottages in the town. The houses, cottages, and c. 2 a. of pasture were leased on lives; c. 49 a. of pasture was let by auction, for £80 in 1833. (fn. 293) About 1868 the charity's income was £202 a year. (fn. 294) Some houses and cottages were sold or demolished c. 1893–1901, and in 1903 the charity had an income of £222 from 45 a., nine houses and cottages, and £1,597 stock, (fn. 295) which rose to a total income of c. £647 in 1950. (fn. 296) The charity had sold the rest of its estate by 1975–6, and invested the proceeds; (fn. 297) in 2000 it had an income of £6,858. (fn. 298)

The Wayland's charity paid for the maintenance of roads by discharging the expenses of the overseers of the highways of St Sampson's and St Mary's parishes and, in place of statute labour, by making payments to the surveyors of the turnpike roads which passed through the two parishes. It often required particular repairs to be carried out, and it paid for paving the streets, building bridges, cutting ditches, and cleansing streams. In 1826 the trustees resolved to make no future payment in respect of roads outside the town, and payments to the surveyors of turnpike roads ceased. About that time the charity paid for major improvements to the town streets and for the town bridge to be rebuilt in the 1760s and in 1854. (fn. 299) In 1872 the Charity Commission authorized the trustees to spend no more than £50 p.a. on lighting the borough, (fn. 300) and the charity paid £50 p.a. towards the cost of street lighting until 1975. (fn. 301) From 1898 to 1936 the charity maintained the Jubilee clock in High Street. (fn. 302)

From 1896, when Wiltshire County Council and Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council became responsible for maintaining the roads, the Waylands charity allowed most of its income to accumulate. Under the Scheme of 1903 the area which should benefit from the charity was defined as the new Cricklade parish, and the trustees were required to pass the charity's income to the two councils; (fn. 303) in 1910 £52 was given to the county and £68 to the district. The money given to the councils was used to lower the rates charged on property in the parish, and in 1974 £818 was given for that purpose. (fn. 304) Under a Scheme of 1976 the charity's entire net income might be spent on any charitable purpose to benefit inhabitants of Cricklade and its neighbourhood. (fn. 305) In 2002–3 it had a gross income of £7,783. (fn. 306)

PUBLIC SERVICES AND UTILITIES

Before the development of county government in the 19th century, public services in Cricklade town and parish were provided by several bodies, Cricklade manor court, the parish vestries, the borough and Wayland's charity.

Police

From the 15th century or earlier Cricklade borough was policed by two constables. By the 18th century the manor court, meeting for the view of frankpledge, appointed one constable for each parish, and also appointed watchmen. (fn. 307) From 1839–40 the town and both parishes were policed by the Wiltshire county force. (fn. 308) In the mid 18th century the court of Little Chelworth manor ordered the erection of stocks. (fn. 309) Stocks stood in Calcutt Street in 1837. (fn. 310) St Sampson's workhouse contained a sealed room, presumably part of the extension built c. 1800; (fn. 311) it may have been what in 1810 was called the borough's blind house, (fn. 312) and the gaol chamber in the 1820s and 1830s. (fn. 313) It was probably in the part of the building which was demolished c. 1840.

A lockup was built in Horsefair Lane, presumably after the parish ceased to control the workhouse in 1835. From 1840 the county force had a police station in the house where the superintendent lived, added to the north side of what is now no. 3 the Priory. This contained no cell and in 1851 the lockup in Horsefair Lane was said to be too weak. (fn. 314) From c. 1850 no. 76 High Street was used as the police station; the lockup was at the north end of High Street behind no. 71. (fn. 315) In the 1880s and 1890s an inspector and four constables were stationed in Cricklade, in the early 20th century an inspector and one constable. (fn. 316)

In 1921–2 a police house incorporating a groundfloor office was built as no. 91 High Street on the site of the tenements called the hospital. (fn. 317) It was lived in by a sergeant in the 1920s and 1930s, when often two constables also lived in the town, (fn. 318) and in the 1940s and 1950s a sergeant and three constables were stationed there. (fn. 319) Since 1962, when the building was altered, the police station has occupied the whole ground floor. (fn. 320)

Fire

There was no fire engine at Cricklade in the 18th century, and in 1723 St Sampson's parish paid for a fire to be extinguished by one brought from Cirencester. (fn. 321) In 1858 a fire engine with a hand pump was bought and kept in a building on Bath Road. Both were paid for by subscription, and from then a committee managed a brigade of volunteers. From the 1920s L. O. Hammond's garage business in Calcutt Street provided the volunteers and an engine with a steam-powered pump, which was pulled to fires by horses or a motor vehicle. (fn. 322) In 1936 Cricklade parish council, dissatisfied with the service, arranged for Swindon fire brigade to attend fires in the parish. (fn. 323)

In 1947 Wiltshire County Council became the fire authority for the whole county, (fn. 324) and in 1950 it converted two of the Nissen huts erected in the Second World War at the south end of High Street to a temporary fire station. (fn. 325) That was replaced by a new one built in 1963 in Bath Road. (fn. 326)

Water, Sewerage and Refuse

A piped water supply for the town was installed by the lord of the manor c. 1734. A water engine and a water wheel were set up in the Thames near the town bridge, a cistern was erected in High Street, and pipes were laid to carry river water to the streets and houses. (fn. 327) In 1840 a water engine house, apparently built after 1830, stood 100 m. below the bridge; (fn. 328) a reservoir remained in High Street in 1857. (fn. 329) This supply may have ceased by the late 19th century, when it was said that the town was supplied inadequately with water from rivers and wells. A new system was installed by Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council c. 1905, pumping water from gravel beds near the Thames to a reservoir at Windmill Hill. (fn. 330) From c. 1935, water was brought to the town from a deep well at Ashton Keynes, and later the town was supplied with water from boreholes at Latton. (fn. 331)

In 1861 the Wayland's charity laid a drain along the east side of High Street to discharge rainwater from the street to the Thames, and later it laid one along the west side. (fn. 332) Pipes carried sewage from the houses of the town to the Thames through the drains, but the Conservators of the River Thames demanded in 1893 that this should cease. (fn. 333) About 1900 the rural district council built new sewage treatment plants on land at the Forty and at Hatchetts, in Latton parish directly across the Thames from the town. (fn. 334) From 1934 all of the town's sewage was treated at an improved facility at Hatchetts. (fn. 335) A sewage disposal plant built in Leigh parish c. 1943 for RAF Blakehill Farm was bought by the rural district council in 1960–1 to dispose of dried sludge from Hatchetts, which was enlarged in 1965–6 to cope with the needs of the increasing population. (fn. 336)

In 1931 Cricklade and Wootton Bassett Rural District Council began to collect refuse from houses in the town, which was tipped into the disused canal outside the town until the 1970s. (fn. 337)

Streets

High Street and Calcutt Street were probably paved by Wayland's charity in the 18th century, (fn. 338) and other streets in the town were paved in the 19th century. (fn. 339) A scavenger to clean the streets was appointed at the manor court's view of frankpledge until the mid 19th century. (fn. 340) Street lamps, paid for by subscription and maintained by the Waylands charity, were erected in 1843, and converted to burn gas c. 1859 when the gasworks was built. (fn. 341) In 1860 St Sampson's parish adopted the Watching and Lighting Act of 1833 and levied a rate for lighting, (fn. 342) and from 1872 the Waylands charity paid £50 a year towards the cost of lighting the town. The gas lamps were replaced by electric light standards erected c. 1929. (fn. 343) The clock erected in High Street to commemorate Queen Victoria's diamond jubilee was maintained by the Waylands charity until 1936, and then by the parish council. In 1914, by order of the rural district council, the houses of each street in the town were numbered. (fn. 344)

Burial

A joint burial committee for both parishes was formed c. 1898 and then re-formed as Cricklade Burial Board in 1899 when the civil parishes were united. A cemetery in Bath Road was opened in 1900, a chapel was built in that year, and in 1901 part of the burial ground was consecrated. (fn. 345) The cemetery was placed under the management of the parish council sitting as the burial board, (fn. 346) and is now managed by the town council. (fn. 347)

Post and Telephone

There was a postmaster at Cricklade from 1781 or earlier and a post office from 1830 or earlier. (fn. 348) In 1866 the inhabitants of Chelworth, Braydon, and Leigh unsuccessfully petitioned the Postmaster General for free delivery of letters and for pillar boxes to be provided, but pillar boxes were set up in 1899. (fn. 349) In 1923 the post office was moved from 29 High Street to no. 39, which incorporated the first telephone exchange in the town; the first telephone kiosk was erected c. 1932. (fn. 350) A new telephone exchange was built in Thames Lane and was replaced by a larger one built off the Purton road at the Forty. (fn. 351)

Gas and Electricity

A gasworks was built in Mutton (later Gas) Lane c. 1859; (fn. 352) a new gasholder was built between 1875 and 1898 (fn. 353) and other new buildings were erected c. 1909. (fn. 354) The gasworks belonged to the Cricklade Gas Company, (fn. 355) later to the Bucks. & Oxon. District Gas Company, (fn. 356) and in the 1920s and 1930s to the United District Gas Company. (fn. 357) It was closed by 1949 and was later demolished. (fn. 358) Electricity for the town was supplied by mains and cables laid by the Western Electricity Supply Company between 1929 and 1931. (fn. 359)

PARLIAMENTARY REPRESENTATION